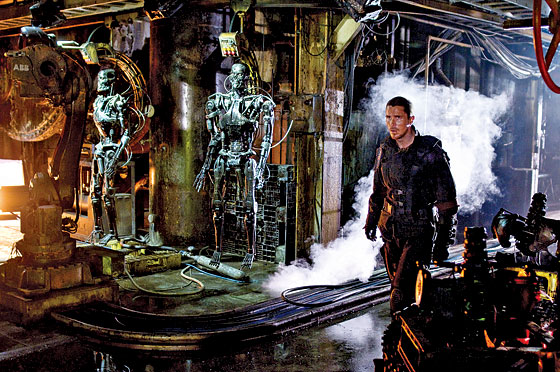

In Terminator Salvation, machines have exterminated most of humankind and run the planet; I think they made the movie, too. This isn’t storytelling, it’s programming—inorganic matter passing for life. James Cameron’s 1984 original and its showy sequel were also mechanical, but their killer ’bots had charm: Arnold Schwarzenegger’s metallic readings and lumpy-jawed bodybuilder arrogance meshed riotously well with the part of a cyborg assassin, and Robert Patrick’s T-1000 was a witty, preternatural blank—with adorably incongruous teacup-handle ears. The fourth time out, the bad machines are steel-skeleton FX, the humans less compelling. It’s not wholly the fault of the director, McG, who decently storyboards the clashes and explosions. As I said, it’s the machines—or, more precisely, the Hollywood Machine that sifts through books and old movies in search of the holy “franchise,” and at strategic intervals generates nonessential sequels.

The Terminator began with a villain and a hero traveling back in time, and the fourth installment isn’t so much an advance of the story as a footnote: This is how we got to where we’ve already been—for 25 years. John Connor (Christian Bale), prophet of the resistance, must defeat the machines and send Kyle Reese (Anton Yelchin) to 1984 to save his mom and deliver a payload of sperm that will grow up to be John Connor. Of course, every time trip has its perils—just ask the Vulcans in the new Star Trek. Maybe in this time loop the machines will kill John before he can kill them. Maybe Kyle will stand too close to an X-ray machine and become infertile. As Sarah Connor exclaims to her son (via cassette tape): “God, a person can go crazy thinking about this”—a line that must have given everyone on set a good laugh. Onscreen, alas, nothing lightens the mood. With McG’s migraine-inducing jerky-cam and monochromatic palette (livened only by splotches of rust), Terminator Salvation puts the numb in numskull.

Minus a fun new terminator, the movie offers a second protagonist, Marcus Wright (Sam Worthington), who’s executed by lethal injection in a nineties prologue after signing away his body to whey-faced scientist Helena Bonham Carter—and then mysteriously bounds naked from some wreckage in a post-nuclear-holocaust 2018 looking remarkably buff. No spoilers here: I won’t deprive you of the pleasure of figuring out his secret for yourself about an hour and a half before the Big Reveal. Worthington, an Aussie, has a brief but vivid role as a studly hooligan in Greg Mclean’s delectable killer-croc picture, Rogue, and he manages to suggest a soul in torment with a minimum of inflection. It’s not that he’s all that winning—it’s that the competition never gets out of the gate.

Millions have viewed via YouTube Bale’s abusive tantrum on the set of this film, and he’s virtually the same on-camera: Chewing out an insensitive cinematographer or snarling at a fellow fighter, he’s equally unpleasant. Bale is a Method guy who tries to become his roles, and in principle that’s fine. I’m in the minority in liking his Batman: His humorlessness resonates with Bruce Wayne. But as the hero of an outlandish sci-fi thriller, he lacks imagination and dash. John’s mission is the apogee of nuttiness: to find his dad, a teenager, and keep him alive to impregnate mom and save the world from an army of titanium-girded Austrian musclemen. But Bale is such a dour prig you wonder why he just doesn’t abort himself in spite.

Steven Soderbergh’s failures are in a different class than other American directors’. My guess is that he doesn’t like to know, going into a shoot, what he’s going to come out with, which is one reason he acts as his own cinematographer and often his own camera operator: He wants to participate in the process, to live with his actors in the moment. I imagine him in the editing room, playing with the overall structure, rearranging scenes and roughening the syntax, approaching his raw footage like a Cubist jigsaw puzzle: Let’s try the nose under the mouth, shorten the leg, allow content to dictate form. Yet there’s something oddly inflexible about him. Soderbergh gets a big idea and sticks with it, even when it’s not working. Maybe he doesn’t know it’s not working. More likely, he doesn’t want to know. He’s a paradox: a control freak who overcompensates by being loose—then can’t let anything interfere with that looseness. He’s rigidly freewheeling.

Soderbergh has set himself multiple challenges in The Girlfriend Experience, all of them formidable—if not suicidal. The first is to build a film around a nonactress, the hardcore-porn star Sasha Grey, an almond-eyed beauty with a disarming self-containment. She plays Chelsea, a high-end Manhattan call girl, and Soderbergh intends to scrutinize that protective layer. He engages assorted nonactors and gives them room to come at Sasha from varying angles. A nameless journalist played by New York’s own Mark Jacobson interviews her, and the scene is cut into multiple parts and inserted at key junctures. Jacobson—warm, shaggy, manipulative as hell—asks questions to ease Chelsea into letting down her guard: arduous work for scant returns. The voluble blogger-critic Glenn Kenny plays a blogger-critic—of call girls! In the movie’s most vivid scene, Kenny is degenerate appetite incarnate, negotiating with Chelsea the price of a good review while paving the way for a career as the Sydney Greenstreet of underground cinema. The central, more scripted relationship is between Chelsea and her live-in boyfriend Chris (Chris Santos), a personal trainer who accepts what she does but is blindsided when a client stirs something deep in her. At least she says it’s deep. We have to take her word for it: As an actress, Grey doesn’t put out. As an actor, Santos seems like a great personal trainer.

The Girlfriend Experience captures a moment in our history: The 2008 election hasn’t happened, but the economy is in a dive, a government bailout is coming, and there’s little in the way of a real president. It’s a desperate limbo—everyone is selling, few are buying. But most of the dialogue is listless, and no matter how much Soderbergh snips and stitches, the movie is a corpse with twitching limbs. It’s rare to watch actors who appear to be improvising (badly) and yet manage so often to step on one another’s lines. The suspense is minuscule: Will Chelsea find love with a client she barely knows or be dashed against the rocks? (Three guesses.) Behind the camera, Soderbergh hyperventilates. In some scenes, the leads in the foreground are blurred while the extras behind them are in focus. It’s as if his unconscious is sending a message.

Terminator Salvation

Directed by McG.

Warner Brothers Pictures. PG-13.

The Girlfriend Experience

Directed by Steven Soderbergh.

Magnolia Pictures. R.

E-mail: [email protected].