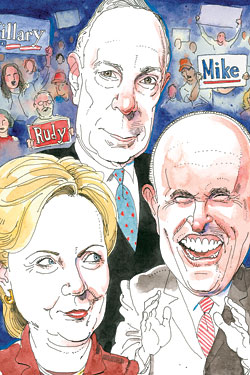

Out of a combination of pragmatism and perversity, we New Yorkers tend to be of two minds about a lot of things, including our politicians. Although I’ve now voted twice for both Rudy Giuliani (for mayor, in 1993 and 1997) and Hillary Clinton (for senator, in 2000 and 2006), Clinton is not my first choice among the candidates running for president, and Giuliani is probably my last choice among the leading contenders. Yet as a civic narcissist—one infected, as John Updike has written, with “the true New Yorker’s secret belief that people living anywhere else had to be, in some sense, kidding”—I find myself pleased by the prospect of both major parties picking New Yorkers to be their 2008 presidential candidates. And the chance that the election could be a serious three-way race among New Yorkers—that is, if Mike Bloomberg announces his independent candidacy in March, after Clinton and Giuliani have their respective nominations sewn up—actually makes me giddy.

The odds of a New York trifecta (or even the Democrat-Republican daily double) have lengthened during the last month, as Clinton’s lead in Iowa and Giuliani’s nationwide have evaporated and eroded, respectively. But according to the most recent national polling, Clinton’s margin over Barack Obama is still substantial, and Giuliani remains the leader among Republicans.

And based on conversations with Bloomberg’s friends and advisers, I’d put the chance that he’ll run at around 50-50 if Obama does not become the presumptive Democratic nominee. Merely switching his registration from Republican to independent last summer made Bloomberg’s poll number in a hypothetical race against Clinton and Giuliani spike to 17 percent; if and when he officially starts running, just as the electorate’s buyer’s remorse is settling in, he will surely pop to 25 percent or more, and I’d be surprised if he didn’t do better in November than any third-party candidate in history. MikeBloomberg.com, with a home page touting his “nonpartisan solutions” to climate change and health care and highlighting Newsweek’s declaration that “he has the money and the message to upend 2008,” gives every appearance of being the site of a presidential candidate–in–waiting.

These three are obviously very different people, but they’re also definably New Yorkers of a broad type. They’re all hardworking, ferociously ambitious, aggressively intelligent, socially liberal, shrewd, and arrogant, respected more than loved. Two out of three live on the Upper East Side, two have published best-selling books, two are ethnic non-Protestants, and two are somewhat scary, grudge-holding lawyers. And they also all have similarities beyond their common New York psycho-geography. None is a very good public speaker. All were born during the same five-year span of the forties. Giuliani, Clinton, and presumably Bloomberg voted for George McGovern in 1972, all have been both Democrat and Republican, and all first ran for office late, in their forties or fifties.

Part of the attraction of Clinton vs. Giuliani vs. Bloomberg would be like that of a subway series in baseball, the intense indulgence of our collective vanity that we live at the epicenter of everything and everyone important in America. Sure, we lost the national capital 217 years ago, and the crucial out-of-town tryouts now take place in Iowa and New Hampshire, but imagine a season in which all the principals (and their managers and handlers) were New York–based. If the nation’s selection of the Most Powerful Person in the World becomes, for the first time ever, a parochial rumble among local familiars—Yo, Rudy! Yo, Hillary! Yo, Mike!—our habitual, somewhat insufferable sense of ourselves as in-the-know insiders will be turbocharged for a generation.

But our bragging rights would be serious and substantive as well. A Clinton-Giuliani race would arguably mean that the modern political ascendancy of the Sunbelt and the South had peaked. And if Bloomberg were to run strongly, politics would indeed be upended—for the better, I happen to think, but in any case for real.

And then there would be the sheer entertainment value, the election unfolding like a grand work of fiction, thanks to the backstories we know better than anyone.

In 2000, New Yorkers had all gathered in the schoolyard for a vicious, epic fight between Giuliani and Clinton for our empty Senate seat—but then Rudy, thanks to his cancer and his adultery, begged off. Now, as a result of 9/11—see, it’s always all about us—our canceled celebrity death match can finally take place, this time vastly more vicious and epic and consequential than the original would have been. Given that Giuliani’s campaign is already focused on slagging Hillary, imagine the vitriol and mutual loathing that could accumulate by next fall.

Almost any predecessor-successor relationship is fraught, but the chill between the current and former mayors is decidedly so. “Now that The Sopranos is over, we have Giuliani-Bloomberg,” says Fran Reiter, who served Rudy as campaign manager and deputy mayor before he turned on her. Giuliani, being Giuliani, has been peeved by what he considers his successor’s “betrayal”—that is, by the fact that Bloomberg is a successful, innovative, tough-minded, crime-reducing mayor whom no one hates or considers a psycho. Giuliani must have been galled by the Daily News poll, earlier this year, in which New Yorkers by a two-to-one margin called Bloomberg the more effective mayor—and by 46 to 29 percent said he’d make a better president. In a race against Giuliani, Bloomberg would be the super-successful businessman, generous philanthropist, and consistent, even-keeled leader versus the tightly wound former prosecutor who has just spent a couple of years dissembling about his previous strong support of gays, immigrants, abortion rights, and gun control. And won’t we enjoy the televised debate moment when Bloomberg asks Giuliani why he left a budget deficit twice as big as the one he’d inherited from a Democrat?

In fact, wouldn’t we relish the native immunity of Giuliani’s two New York opponents to his compulsive I-survived-9/11 shtick: When a fellow New Yorker is running for president on the basis of the fact that he didn’t crumple after the attacks—hey, neither did the rest of us—and by pandering to outlanders’ fears of future attacks, we’re not buying.

It goes without saying that any presidential election is a giant media circus. But news media are us: What happens to the political meta-narrative-feedback loop if all the candidates govern or represent and/or live here, in the headquarters city of the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, The New Yorker, the Associated Press, CBS, ABC, NBC, MSNBC, and Fox News? It could be our equivalent of the new cern particle accelerator in Switzerland’s becoming fully operational, which will also take place next year. In neither case, probably, will the universe be destroyed as a result. But the unprecedented supercollisions and energy release are thrilling to contemplate.

The fact that the nation may well elect a New Yorker president seems like an astounding reversal of fortune. Yet a look at history suggests that Americans’ regard for New York City may run in cycles.

From the twenties to the mid-sixties, from Fitzgerald and the Algonquin Round Table through our last World’s Fair, New York was the cosmopolitan cat’s meow—the setting for the great screwball film comedies, the city of theater and publishing and advertising when all three were at their cultural zeniths, the wellspring of America’s global primacy in art, the place where television was established as the center of a new hegemonic media monoculture. In every presidential election from 1928 to 1948, a New Yorker was a major-party nominee, and one of them, the greatest president of the century, won four times. (And speaking of subway series, that’s also the era in which thirteen out of the fourteen happened, including seven of the ten World Series played between 1947 and 1956.)

But then came the city’s spectacular crack-up, in the sixties—Kitty Genovese’s horrific public murder, followed by a tripling and quadrupling of crime rates in just a few years, plus four crippling and contentious municipal strikes (transit, sanitation, and the teachers, twice) between 1966 and 1968. To the other 200 million Americans, the New York City brand became profoundly, horribly sullied. The moment Mayor Lindsay gamely insisted that ours was still “a fun city,” Fun City became a purely ironic catchphrase, since we and the rest of the country knew that New York had suddenly become the international icon of urban danger and entropy, the setting for Midnight Cowboy and Mean Streets instead of I Love Lucy or On the Town. In 1972, Johnny Carson moved the Tonight Show to L.A., and by 1975 the City of New York was within an inch of bankruptcy. The famous Daily News headline might as well have been AMERICA TO CITY: DROP DEAD.

But it’s in the nature of cycles to find a bottom and then creep back up. Movies and TV started softening up the provincials to rediscover New York; Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), the Letterman show (1982), Seinfeld (1990), and Friends (1994) amounted, in the aggregate, to a long-term rebranding campaign to make our countrymen fond of us again. And the destruction of the World Trade towers, the astounding TV event of our age, was the capper. Not only are we smart, fun, and funny, but also fearless—2,752 of us died for your sins, America.

Beyond the upbeat, upscale showbiz iconography, however, and before the collective victimization and heroism of 9/11, we had pulled out of our municipal death spiral. Starting in the nineties, the crime rate dropped almost as fast as it had risen in the sixties and early seventies, and homicides are now as rare as they were back in the good old days before everything went kerflooey. A time traveler from the era of Sleeper would find the conditions of today’s subways—free of graffiti, air-conditioned—and of certain neighborhoods (Harlem, Times Square, the Lower East Side, Fort Greene) literally fantastic. Some of us loved a lot about messed-up, noir New York as well, but the trade-offs we’ve made—most notably, those five daily homicides that no longer occur—are worth it.

What was once the prime example of an ungovernably out-of-control metropolis has, during the past 30 years, become exactly the opposite, a large-scale case study in can-do civic common sense. We’re still liberal, not in precious Santa Monica/Berkeley ways, but in the more old-fashioned sense of a freethinking, serious-minded inclination to try whatever works, whether it requires less government or more. In the last presidential election, we voted almost unanimously against the wild-eyed ideologue candidate, and in four mayoral elections in a row we’ve chosen the (at least nominally) Republican candidate. In other words, we’re now a beacon of reasonableness, competence, and trans-ideological pragmatism.

The rest of America seems to get this. Our junior senator is the most conservative of the Democratic candidates, our former mayor the most liberal of the Republicans. Sure, they and Bloomberg are opportunists (they’re New Yorkers!). Yes, Bloomberg would be purchasing the presidency (again, so New York—and unlike TR and FDR, he made his own fortune). But all three embody a certain reassuring philosophical mongrelism, and a tilt toward the center. As a Goldwater Republican undergraduate, Clinton fancied herself “a mind conservative and a heart liberal.” Two decades ago, as he was first running for office, the former Bobby Kennedy Democrat Giuliani admitted that apart from “law-enforcement matters … I’m more moderate or liberal, depending on which position will solve the problem.’’ And Bloomberg, having created a visionary business from scratch, is candidly instrumental and whateverish about party affiliation. Unlike Reagan or Bill Clinton, none of them seems especially likable, somebody you really want to have a beer with … but so what? Maybe Americans are ready to abandon the delusion that presidential candidates are running for good-buddy-in-chief.

And speaking of circling forward from and back toward the sixties, this possible presidential contest among New Yorkers, as a famous Yankee once said, is like déjà vu all over again. In 1964, a scandalous divorce and remarriage damaged the presidential campaign of a liberal New York Republican who had been the front-runner for his party’s presidential nomination. The same year, a family member and close adviser of the previous Democratic president opportunistically moved to New York to run for Senate, and a few years later ran for president. At the same time, a rich Republican Upper East Sider was accused of “trying to buy his way into City Hall,” then got reelected, switched parties, and declared for president. Nelson Rockefeller, Bobby Kennedy, and John Lindsay never ran against each other nor, of course, made it to the White House. Yet while pundits always say that the last New Yorker to become president was FDR, I beg to differ. The candidate who beat Rockefeller for the nomination and finally won the presidency in 1968 had spent the previous five years working as a lawyer on Wall Street and living with his family at 62nd and Fifth; he then spent his twenty years of retirement in a New York suburb closer than Chappaqua to Central Park. Richard Nixon was as much a New Yorker as Hillary Clinton.

Of course, New York City didn’t vote for Nixon for president, just as most of us aren’t about to vote this time for our boy Giuliani. Home-team rooting only goes so far. Personally, I’m for Obama, not least because his election would hasten the end of a national politics that so often amounts to endless, stupid, fantasy reenactments of the battles of the late sixties. But if Iowans and New Hampshirites and South Carolinians dash that happy, redemptive dream, well, then I’m totally psyched—“We’re hangin’ a sign / Says VISITORS FORBIDDEN / And we ain’t kiddin’!”—for the mother of all New York gang fights.