You can have your Prado, your National Gallery, your Hermitage. The Met is not only the finest encyclopedic museum of art in the United States; it is arguably the finest anywhere. Unlike the Louvre, it is comfortable and easy to use: You can get to the work without navigating hot spots of tourists, and you never feel like you’re in someone’s former palace. Here’s a tour of some of my favorite things, including easy-to-overlook items along with the can’t-miss ones. No matter what you seek out, the Met will turn you into a perpetual student, visiting the self as well as the entire world.

1. HEADDRESS EFFIGY (HAREIGA)

From Papua New Guinea (late nineteenth–early twentieth century)

Made by the Chachet Baining people of New Britain, Papua New Guinea, this object looks like a tree trunk with a massive swollen head, tattooed eyes, eyebrows, and a gaping mouth. She presides over this hall like an extraterrestrial empress emitting waves of visual, psychic, and erotic power.

2. ALLEGORY OF THE FAITH

By Johannes Vermeer (1670)

Of the Met’s five Vermeers, this is the weakest, if there is such a thing. But it is easy to miss its real point: Everything in the picture is set up. Artifice and breaking with reality are the content; the woman symbolizing the church is obviously a posed model. It’s seventeenth-century Cindy Sherman.

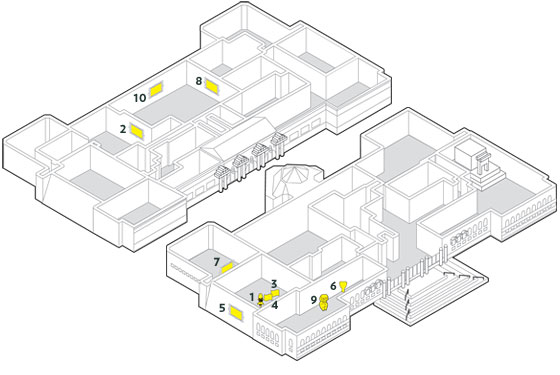

3. ETHIOPIAN ILLUMINATED GOSPEL

(Late fourteenth–early fifteenth century)

This Bible contains 24 full-page illuminations. In one, showing the entry of Christ into Jerusalem, the Apostles hover around him as he is poised at the still center; their Picasso eyes pull us in. Flat and Byzantine, visionary and captivating, all at once.

4. MARSHALL ISLANDS NAVIGATIONAL CHART

(Late nineteenth–early twentieth century)

This grid of coconut midrib, sticks, and fiber looks like something Piet Mondrian, Richard Tuttle, Joaquín Torres-García, or Paul Klee might have made. But it is a working tool— a mariner’s map showing currents and sea lanes. Imagine if our maps to the moon were constructed so lyrically and physically.

5. THE DREAMER

By Pablo Picasso (1932)

The Dreamer gives us Picasso, age 51, the Cubist and the formalist but also the sexually obsessed and love-struck swain. It’s a dreamy, steamy postcoital picture of Picasso’s young mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, asleep. We see what Cubism may be about on a primal level: The urge to see vulva, buttocks, mouth, eyes, anus, and navel all at once.

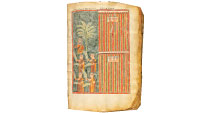

6. GREEK KRATER

Showing prothesis scene (the laying out of the dead). Attic (ca. 750–735 b.c.)

A combination of cave painting, pictograms, silhouettes from Mars, and Zap Comix, this large ceramic urn’s paintings constitute a scene worthy of Cecil B. DeMille. A funeral procession, chariots, soldiers bearing spears: Its decoration is narrative art at its finest, and maybe the beginning of movies.

7. THE CATHEDRALS OF ART

By Florine Stettheimer (1942)

This batty, beautiful candy-colored picture shows the grand staircase of the Met flanked by pillars that read AMERICAN ART and ART IN AMERICA. On the left is MoMA, its director Alfred Barr relaxing in front of a pair of Picassos. Figures from Matisse and Rousseau dash by. The artist appears as a sexy young thing, joined by figures from the early American avant-garde. A totem pole, a birthday cake, and a great painting.

8. MEZZETIN

By Jean Antoine Watteau (1718–1720)

This powdery but powerful little picture of a man in a park, strumming and singing to an unseen someone, has the dignity, vulnerability, delicacy, and humanity of Mozart’s music. When you see this lone character, you are deeply in touch with the way in which all the world’s a stage. It shows the birth of our sensibility of doubt, loneliness, and love.

9. FEMALE FIGURE

Cycladic, Neolithic (ca. 4,500–4,000 b.c.)

This is the oldest figurative sculpture on exhibit at the Met, and it’s a powerhouse. An elegant headless female figure, she has enormously exaggerated buttocks and thighs like thickly padded plates. These objects may have been meant to ensure pregnancy, aid in safe childbirth, and assist in breast-feeding. It’s impossible to prove, but I think the first great artists are likely to have been women.

10. THE HARVESTERS

By Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1565)

The yellowest painting in premodern art history, The Harvesters is a picture Karl Marx and Coco Chanel could love. It’s the first realistic depiction of peasant workers’ strengths, shortcomings, and daily habits. The harvester snoozes in the foreground; you can follow him to men and women gathering wheat, then to a wagon carrying the product to ships sailing for foreign ports. You’re seeing not just a gorgeous golden picture but an entire section of society at work.

See Also: Jerry Saltz’s Video Tour of the Met