It became known as a “death trap.”

In July 1875, the Rockaway branch of the then-Southern Railroad of Long Island, not far from New York City, had seen two accidents in a little over a week. One was fatal.

Executives of the Long Island Rail Road, which merged with the Southern Railroad and other rivals the following year, were scrambling to find workers to completely rebuild the tracks on that line.

They needed it done quickly, ahead of the 1876 beach season, and decided there was one group with the experience to do it right: the Chinese.

“Basically the whole future of the railroad depended on their [the owners] getting the public’s confidence back,” said Stanford University professor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, who uncovered this piece of history and wrote about it in the forthcoming book, “The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad.”

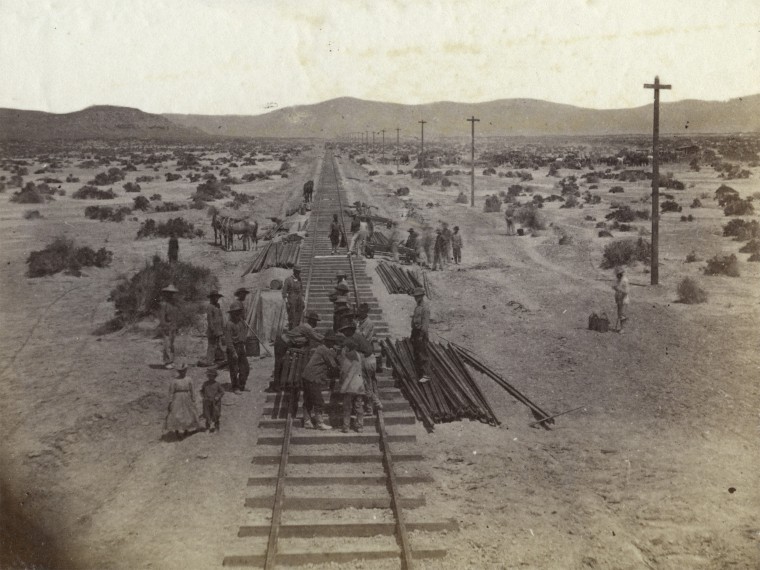

In the two decades following the 1869 completion of the first transcontinental railroad — a project that linked the nation and which celebrates its 150th anniversary May 10 — Chinese railroad workers fanned out across the country to help build, maintain and repair at least 71 other rail lines, Fishkin writes in her chapter entitled “The Chinese as Railroad Builders after Promontory.”

While the Chinese, who had made up around 90 percent of the Central Pacific Railroad’s labor force, brought their expertise to railroads in the West, Northwest and Southwest, Fishkin found evidence that they also plied their trade on lines in the South, Midwest and even the Northeast.

Among them was the LIRR, chartered in 1834 and one of the nation’s oldest railroads still operating under its original name.

“This was one of the finds ... that really surprised me,” Fishkin said.

PLYING THEIR TRADE

May 10, 1869, marked a new beginning for a fractured country recovering from the Civil War.

Track laid by the Central Pacific (starting from Sacramento) and the Union Pacific Railroad (building from Omaha) met that spring day in Promontory, Utah, signaling the completion of America’s first transcontinental railroad.

A boon to the economy, the line significantly reduced cross-country travel time from months to less than a week. Goods, including produce and natural resources, could now be moved more quickly and cheaply from coast to coast.

The more than 10,000 Chinese laborers of the Central Pacific, many of them migrants from China, helped make this possible. At the same time, whites were growing increasingly hostile toward the Chinese, whom they accused of squeezing them out of work by taking jobs at lower pay.

Railroads, meanwhile, witnessed tremendous growth between 1869 and 1889, with track mileage more than tripling across the country, from 47,000 to more than 161,000 miles, Fishkin writes.

The Union Pacific in Ogden, Utah, which did not hire any Chinese for the first transcontinental railroad, had brought on 225 Chinese railroad workers by June 1, 1870, according to “The Chinese as Railroad Builders after Promontory.” The Chinese found jobs at the company repairing the line and working in its coal mining operations, particularly west of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The threat of violence, sometimes deadly and at the hands of unemployed whites, had become an ever-present reality for the Chinese. Yet in the two decades after the golden spike was hammered in at Promontory Point, the Chinese railroad workers pushed into virtually all corners of the United States, performing work they so excelled at and for which they had burnished an impeccable reputation.

“Whenever there was a particularly difficult and challenging portion of a rail line to be built during the 20 years after 1869, the Chinese were often brought in to do it,” Fishkin said.

WEST MEETS EAST

New Jersey was the first stop on the East Coast for Chinese railroad laborers. They arrived in Jersey City, across the water from Manhattan, in the fall of 1870, Fishkin writes.

Some 150 men, the first team of a gang of 500, were tasked with building a segment of the New Jersey Midland Railroad that cut through a “rocky and uncultivated region,” according to “The Chinese as Railroad Builders after Promontory.”

Whenever there was a particularly difficult and challenging portion of a rail line to be built during the 20 years after 1869, the Chinese were often brought in to do it.

Shelley Fisher Fishkin

Fishkin cites a New York Times article reporting that the whites hired for the job left “when the work was heavy and difficult.” Ultimately, the reputation of the Chinese workers is what led to them being contracted for the Midland Railroad, the article noted.

Then, around six years later, executives with the LIRR in neighboring New York had a weighty decision to make.

In the summer of 1875, what would soon become the then-Rockaway branch of the LIRR saw two accidents within nine days, one of which caused nine deaths, according to Fishkin.

An inquest revealed that the poor condition of the tracks and roadbed were to blame, the rails and ties having been laid in beach sand. Travelers ended up switching to a rival line, Fishkin said, refusing to ride what they had dubbed a “death trap.”

With the 1876 beach season on Long Island fast approaching, the railroad needed to act fast.

“The owners really felt that unless they got the best builders in the world to repair the line, they were done,” Fishkin said.

And so they brought in the Chinese.

Newspaper articles Fishkin found reported that between 120 and 250 Chinese arrived around June 1876. The New York Sun, in a piece that published June 4, 1876, said the workers were paid 70 cents a day.

The men lived along the line in train cars converted into bunkhouses and were also provided with cooking equipment, according to a June 2, 1876, article in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Train service was suspended to Rockaway while the Chinese made repairs.

In a matter of weeks, work on the branch was complete, and it was up and running again for the summer crowds.

RECOVERING HISTORY

Who these workers were remains a mystery, part of a bigger puzzle that Stanford scholars such as Fishkin have been trying to solve.

A spokesperson for New York State's Metropolitan Transportation Authority, of which the LIRR is a subsidiary, provided contact information for an LIRR historian, who in turn suggested reaching out to another historian mentioned in Fishkin's bibliographic essay. Voicemails left with that individual were not returned.

Though scholars have discovered evidence that many who built the first transcontinental railroad were able to read and write in Chinese, Stanford researchers have found no letters or journals from them, perhaps because they were destroyed or not preserved during the ensuing social upheaval in China.

The project said some documents have, however, been left behind by the Chinese who worked on other lines after 1869. But Fishkin said she’s located no records with the names of the Chinese who repaired the LIRR or where they were sent in from, though she presumes San Francisco.

In the end, the Chinese were an indispensable part of building up the nation’s railway infrastructure during the latter half of the 19th century, Fishkin notes.

As for the LIRR’s Rockaway branch in 1876, the Chinese were the unsung heroes who restored customer confidence in a line that riders were afraid to take.

“And the story,” Fishkin added, “completely disappeared from history.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.

More from NBC Asian America's series on the Chinese railroad workers: