An artist’s inspiration can come from anywhere, even a road trip on I-80.

For Lin Zhi, it happened in August 2001 while driving from Missouri to his new job in Seattle at the University of Washington. With a AAA TripTik travel planner by his side, Lin noticed he was passing Green River, Wyoming, not far from a place called Rock Springs.

The name rang a bell.

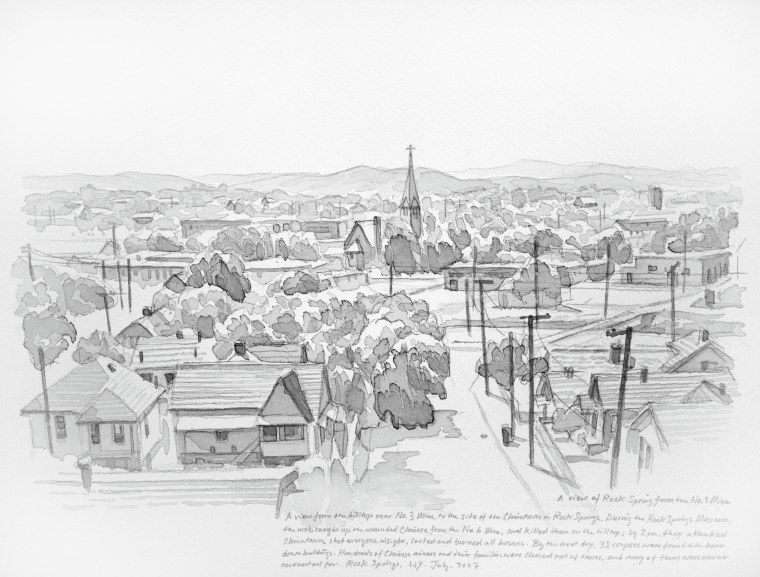

Back when he was a kid growing up in China, during the Cultural Revolution, he had read about Rock Springs, the site of one of three Chinatowns in Wyoming in the late 19th century, in a book from his dad’s study. Rock Springs was the site of an 1885 massacre in which around 28 Chinese miners were slaughtered, their Chinatown destroyed, by whites who resented them for taking work for less pay.

The book also mentioned the Chinese who helped build the first transcontinental railroad, which on May 10 celebrates 150 years since its completion.

As Lin continued along I-80 in his Nissan Xterra, the sun setting amidst the towering Green River Cliffs, a train passed him by on the river’s south bank. Realizing that it was coming from California, the start of the western portion of the first transcontinental railroad, Lin made a connection to the more than 10,000 Chinese who worked for the Central Pacific Railroad.

Lin had found his next subject — raising social awareness about the Chinese railroad workers’ experience.

“I want to make American history inclusive, open,” he said in a phone interview.

Lin is among the artists, photographers, journalists and academics from mainland China and Taiwan — as well as scholars from Stanford University’s Chinese Railroad Workers Project and Chinese American advocates — seeking to recover this often overlooked period of history through a variety of mediums.

For Michael Kwan, president of the Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association, the mission is personal.

“We don’t want other people telling our story,” said Kwan, whose great-great grandfather worked for the Central Pacific. “We want to tell the story.”

‘INVISIBLE & UNWELCOMED PEOPLE’

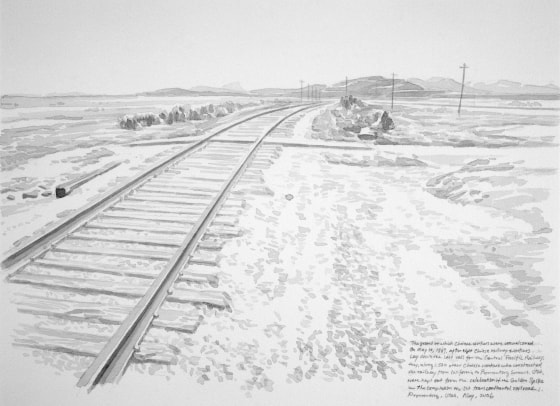

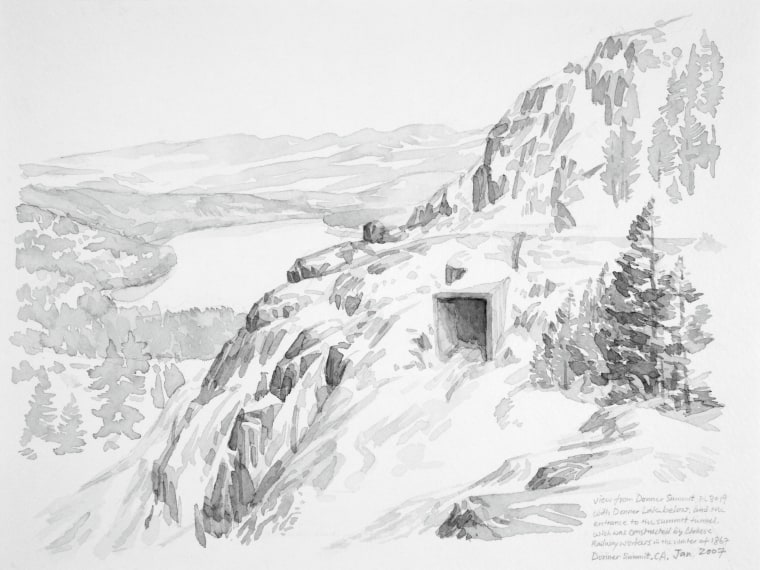

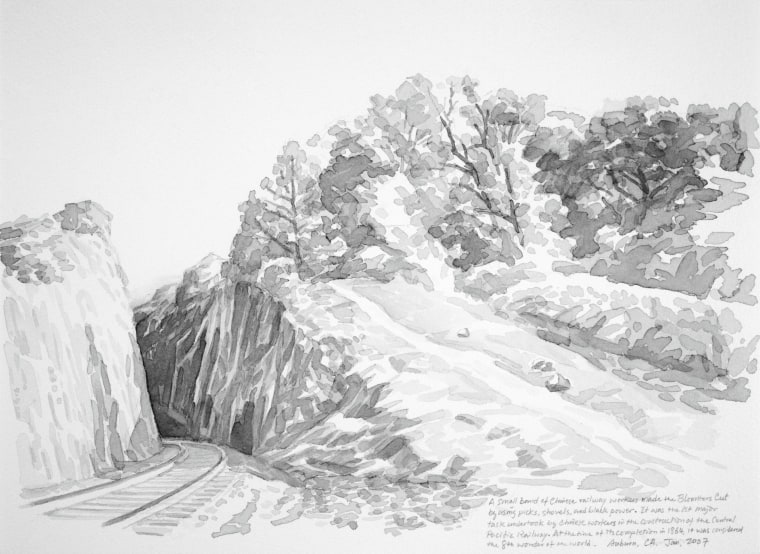

Lin, an art professor at the University of Washington School of Art + Art History + Design, began work in 2003 on a watercolor studies project about the Chinese railroad laborers entitled “Invisible & Unwelcomed People.”

For the next three or four years, he traveled multiple times during different seasons to key spots in California and Utah where the Chinese had worked on the railroad.

Before embarking, Lin would do his homework, consulting historical photographs, studying archives and planning his routes. Once on the scene, he navigated cliffs and summits, trekked across rivers and streams, and descended into deep valleys and icy tunnels.

Lin said he sketched what he saw onsite and finished the works in his studio, using photos he took as references. The watercolor studies were painted “in a very light and subtle way, as though recalling faint memories,” Lin writes in an introduction to his work.

That he did this with Chinese ink and a Chinese brush on western watercolor paper was an intentional move.

“There is at least a portion of American history written with a Chinese contribution,” Lin explained.

His 9-by-12 inch sketches are designed to draw the audience in and to engage them intimately, much like how one might interact with personal journals or a family photo album, the artist said. Small handwritten descriptions on the watercolor paper, a technique borrowed from Chinese literati paintings, heighten that effect.

Absence is what’s particularly noticeable in these works, which recall tranquil landscapes belied by untold Chinese suffering. Whether a scene from Bloomer Cut or Donner Pass, two California locations where the Chinese had labored intensively on the Central Pacific, no workers are featured.

This too is deliberate, a choice born out of frustration of largely being unable to locate photos or identify names of Chinese railroad workers, according to Lin.

“They are faceless, they are invisible,” he said.

Lin has devoted more than a decade of his life to tracing the history of Chinese workers in America’s west. He has current and upcoming exhibitions in Utah and Nevada, including a video projection installation entitled “‘Chinaman’s Chance’ on Promontory Summit.”

Lin said he hopes his work encourages people to think about present-day anti-immigrant sentiment in the context of how the Chinese were mistreated in the 19th century and the railroad workers erased from history.

“I do think society is making change,” he said. “But sometimes it’s one step forward, two steps back.”

PHOTOGRAPHING ABSENCE, RECOVERING HISTORY

Unlike Lin, Beijing native and freelance photographer Li Ju never knew about the Chinese railroad workers while growing up in China.

The 60-year-old retired computer engineer, who has always enjoyed studying old photographs, said he learned of this history while visiting the United States with his wife.

Having toured many American national parks, Li said he was originally looking to take a cross-country trip that followed the old Pony Express, a mail service route from 1860 to 1861. Then, around nine years ago while in Sacramento, he spotted the California Railroad State Museum not far from a statue commemorating the starting point of the Pony Express.

Li went inside and discovered photographs of Chinese laborers working on the railroad, their hair braided in queues, a hairstyle worn during the Qing dynasty.

“Initially, I assumed they were constructing a railway in China,” Li said, speaking in Mandarin, in an interview via WeChat. “Later, I took a closer look at the written descriptions of these photos, only to find out that these were Chinese who worked on the U.S. railroad.”

His interest piqued, Li said he traversed the first transcontinental railroad route 10 times since 2010, taking hundreds of photographs at various stops along the line, including key locations where the Chinese did some of the most demanding, most dangerous work.

In deciding where to visit, Li first combed through photos from Central Pacific Railroad photographer Alfred A. Hart. He then went to spots such as the Summit Tunnel — where Chinese workers had to brave hazardous weather and deadly conditions to bore through solid granite — and photographed scenes from the same perch as Hart.

“Unless you physically go to those locations, it’s difficult to understand just how difficult it was for them in that environment,” Li said.

We don’t want other people telling our story. We want to tell the story.

Michael Kwan

In 2012, Li learned that Stanford University had started the Chinese Railroad Workers Project and decided to reach out.

“Li Ju just turned up one day,” recalled Shelley Fisher Fishkin, a Stanford professor who is the project’s co-director.

Li shared his photos with the project, whose website features some of them juxtaposed with ones taken by Hart. He has also blogged about his trips in Chinese, has collaborated on a 2015 photo book published in China entitled “Footsteps of the Silent Spikes: in Memory of Chinese Railroad Workers in the United States,” and has had his work displayed at exhibitions in the U.S and China.

Thinking back to his career as a computer engineer, Li said he never imagined he would one day play a role in introducing people in China to the contributions and sacrifices made by the Chinese who built the first transcontinental railroad.

“For the Chinese and U.S. governments, this history is one in which both sides have the greatest common understanding,” he said.

GIVING THEM THEIR DUE

Over the years, the Chinese railroad workers have had their story chronicled in a variety of ways, whether in print, through art, or on stage.

The fruits of that collective labor will be on display during the 2019 Golden Spike Conference, organized by the Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association. It officially kicks off May 8, two days ahead of the 150th anniversary ceremony at Promontory, Utah.

While the Chinese railroad workers’ story still often gets short shrift in U.S. classrooms, the Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association has been doing its part to ensure schoolchildren learn about this history.

Kwan, the president, said they’ve been working directly with educators to build new curricula, and also working with the state of Utah to ensure that curricula is included.

Advocates are optimistic that the Chinese railroad workers are finally getting their due.

“I absolutely have hope that it’s going to change — because we’re changing it,” he said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.

More from NBC Asian America's series on the Chinese railroad workers: