Six years ago, hedge-fund manager David Einhorn made a speech at an annual investment conference about a stock he didn’t like—a mid-cap financial company called Allied Capital—and the world came crashing down on top of him. He was investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission for conspiring with other investors to sink the stock. Allied stole his personal phone records in an attempt to prove the conspiracy. An article in The Wall Street Journal compared his treatment of Allied to “a mugging.” New York’s then–Attorney General, Eliot Spitzer, vowed to do his own investigation. And Einhorn’s wife, an editor at the financial weekly Barron’s, mysteriously lost her job.

The repercussions of that one speech dragged on for years, an experience that would have embittered most people, or at least have made them back off. But Einhorn kept digging at the company, ultimately finding evidence of fraud that made his initial report seem tame. Then Einhorn took a very unusual step for a hedge-fund manager, most of whom would rather you didn’t know their names, much less how they run their businesses. He wrote a very candid and illuminating book about his firm, Greenlight Capital, and the complete Allied ordeal. The purpose, he says, was not to become famous or to settle scores; it was to tell people that he had been right all along. He wanted them to see the Allied story as having a “bigger meaning”—that the political, financial, and media Establishments can, and do, conspire to quash truth-telling.

Fooling Some of the People All of the Time was published just in time for this year’s iteration of the same conference. His plan was to go there and give a talk about the book.

In the hedge-fund world, this event, known as the Ira W. Sohn Investment Research Conference, is a big deal. People pay up to $3,250 a seat to hear a dozen or so highly regarded investors pitch an idea. It’s a charitable event, benefiting pediatric-cancer programs, but it’s also a heavyweight Wall Street ritual, with serious profit opportunities at stake.

A few days before this year’s conference in May, Einhorn and his analysts at Greenlight had a private call with Erin Callan, the then–chief financial officer of Lehman Brothers. In two previous speeches at other investing conferences, Einhorn had raised doubts about Lehman; in April, he had explicitly stated that his firm was shorting Lehman, meaning that it had borrowed stock and sold it, with the idea that the firm would replace it at a later date when the stock declined in value (in essence, a bet that the stock would go down, not up). Very few people publicize their shorts, and when Einhorn did, it got Lehman’s attention. The conversation with Callan was to give her a chance to explain discrepancies he had uncovered between the firm’s latest financial filing and what had been discussed during its conference call about that filing.

That very week, a glowing profile of Callan had appeared in The Wall Street Journal, describing her in the headline as “Lehman’s Straight Shooter.” But she’d only been on the job six months and her background was as a tax lawyer, not in finance. She was evidently not prepared for the complexity of Einhorn’s questions and tried to bluff her way through. “The conversation was reminiscent of the ones I had with Allied,” says Einhorn. “We had our questions, we were organized, but she was evasive, dishonest. Their explanations didn’t make any sense.”

And so Einhorn, his sense of righteousness piqued, made a fateful decision: to use the conference to skewer Lehman Brothers. Given the abuse he’d received after he eviscerated Allied, he had to know that this might also have unpleasant consequences. But he was determined to out Lehman as emblematic of the greed and arrogance that had caused the credit crisis in the first place.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, May 21, he took the stage at the Rose Theater at the Time Warner Center to a rock-star reception. As an attendee told me later outside the auditorium, “He’s one of the guys who attracts the swarm.” Einhorn is something of a legend on Wall Street, not only for his investing prowess—25 percent average annual return for the twelve-year life of Greenlight—but also because of an unusual achievement: An accomplished bridge player who has played against Jimmy Cayne of Bear Stearns fame, he took up poker on a lark—and won $660,000 at the 2006 World Series of Poker. But Einhorn is entirely lacking in Vegas bravado. He’s mild-mannered to a fault. Which give his utterances all the more power.

Dressed conservatively in a dark suit and tie, Einhorn explained that he was there to speak, despite the possibility of legal and personal attacks, because “I believe it is important and the right thing to do.” The ratio of BlackBerrys to humans in the room was probably greater than one to one, and they all seemed to light up simultaneously. This was going to be good. Einhorn proceeded with a bracing analysis—including a recap of the Allied saga and a careful dissection of Lehman’s recent financial filing—that had all the moral fervor of a prosecutor’s closing argument. It was as if he were putting away a killer. His firm had a short position on Lehman Brothers, he maintained, not only because Lehman had fudged its numbers but because its recklessness had put the financial system as we know it at grave risk. He ended with a call to federal regulators to “guide Lehman toward a recapitalization and recognition of its losses—hopefully before federal taxpayer assistance is required.”

As Einhorn left the stage to thunderous applause, the moderator came back on and said, “Six years ago, Allied stock opened down 20 percent the day after David spoke. We’ll see where Lehman opens tomorrow.”

Einhorn had just invited the world to fall on his head for a second time.

In Greenlight Capital’s first quarterly letter to investors, Einhorn and his original partner, Jeffrey Keswin, signed off with a quote from the noted philosopher Ken Griffey Jr.: “I don’t consider myself a home-run hitter. But when I’m seeing the ball and hitting it hard, it will go out of the park.”

That was 1996. The firm had just $900,000 in assets, more than half of which came from Einhorn’s parents back in Milwaukee. It was barely enough to rent an office—they made do with a single windowless room. Twelve years later, Greenlight has over $6 billion under management. Einhorn has hit many balls hard, and some of them have gone to the moon.

Though Allied tried to brand him in the public eye as a ruinous short seller, it is difficult to overstate Einhorn’s stature within the hedge-fund community. His peers respect him personally—“A super-high-quality human being,” says Bill Ackman of Pershing Square Capital, who has known him for about eight years—and more than that, they revere his acumen as an investor. He is, for the most part, an old-fashioned stock picker. Though he does engage in short selling, most of his positions are long, and they include companies like Microsoft and Target. Unlike other types of funds, Greenlight doesn’t use borrowed money, or leverage, to amplify small profit spreads, nor does the firm rack up huge trading volume. The nine analysts who work for Einhorn take weeks, if not months, to research companies, and when they find one that he likes—or doesn’t like—he tends to hold the position for a long time. Given this approach, Einhorn can’t afford to be wrong very often, and he hasn’t been. If you had given him $1,000 in 1996, he’d have turned it into $14,600 by now.

In the larger Wall Street community, however, the view of Einhorn is somewhat less fawning, owing in part to the fact that he has established himself as a critic of contemporary investment-banking practices. “The investment banks outmaneuvered the watchdogs,” he said at Grant’s Spring Investment Conference in April. “With no one watching, the managements of the investment banks did exactly what they were incentivized to do: maximize employee compensation. Investment banks pay out 50 percent of revenues as compensation. So more leverage means more revenues which means more compensation.”

Lehman Brothers has been Einhorn’s largest target to date, and it’s a battle that has riveted the financial world. When Bear Stearns had to be bailed out by the Federal Reserve, it was widely rumored that Lehman would’ve been the next one to go down. Spared the worst, Lehman was allowed to borrow from the Federal Reserve against collateral that nobody in the private sector would’ve accepted—and confidently assured investors that it had the wherewithal to make it through whatever remained of the credit crisis. But in this fragile environment, the last thing the firm can afford is a short seller with credibility in the hedge-fund world.

There have been, by all accounts, a lot of hedge funds shorting financial stocks. But the only prominent investor putting his name, and his face, to a singular position has been Einhorn. The predatory nature of short selling drives the target companies mad—“I will hurt the shorts, and that is my goal,” vowed Lehman Brothers CEO Richard Fuld at the firm’s annual meeting in April—and it doesn’t tend to go over well with the public, either. The notion of profiting from a company’s misfortune, as vital as it might be to the efficient running of the market, is anathema to people outside the industry, so much so that precious few investors do it publicly anymore. It’s too easy to look like a scoundrel who’s out to destroy companies and put people out of work. Even Jim Chanos, the short seller who smoked out Enron, is reviled in some circles—because thousands of people lost their jobs and because he made money off it.

But Einhorn is remarkably unfazed by the vitriol he stirs up. He sees no conflict between his public moralism and the fact that he stands to profit from it. He has a profound sense of duty, and an almost innocent belief that if you’re right, nothing else matters.

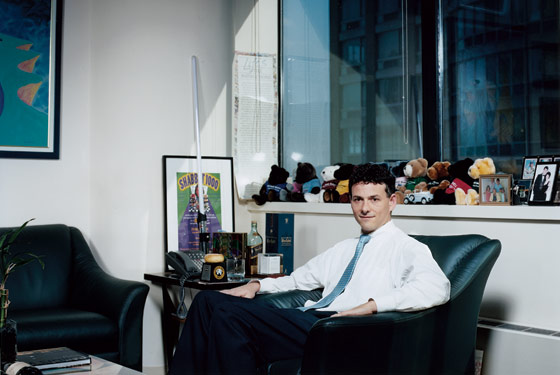

Greenlight Capital occupies a single high floor of a nondescript modern office building near Grand Central. It’s as quiet and orderly as a library. There is a game room with a pool table and a bar, but it doesn’t look like it’s seen many wild parties lately. The room also contains a couch on which Einhorn often takes an afternoon nap—he’s very serious about his naps. Twenty-five people work in the office, including a single trader who sits in a small, high-tech cubby next to Einhorn’s corner office. Though he lavishes much praise on his “team,” Einhorn is to Greenlight what Kobe Bryant is to the Lakers.

Early last month, just before his appearance at the Sohn conference, Einhorn sat in his semi-neat office and discussed how he came to single out Lehman among all the other reeling financial companies. He has black curly hair, cut short and neat, and was wearing in a blue dress shirt, no tie, pleated khakis, and loafers, a vision in Banana Republic. There’s an air of the Boy Scout about him. He’s tall, slight, and has a nasal, high-pitched voice. He is 39 years old, but could easily be mistaken for someone half his age.

Einhorn runs his firm in a self-consciously humane way. High performance is expected, but there is no cracking of the whip and no overbearing hierarchy. Office doors are open; people tend not to work crazy hours. I asked him if it’s true, though, that he starts his own workday at two in the morning. He winced slightly. “My goal is to get home every day in time for dinner with the family”—he lives in Westchester and has two girls and a boy—“and then we play with the kids for a while, and then I go to bed around the time they do and sleep from nine to three or nine to four. It’s the same six hours everyone else gets. I’d just rather do my e-mails and my reading in the morning rather than late at night, that’s all.”

He doesn’t spend much time playing poker anymore. He took it up mostly for the purpose of playing at the World Series; all he really did to prepare was read a couple of books and play a bit with friends and online. But that was enough to finish in eighteenth place with a big chunk of prize money, which he donated to charity. “Texas hold ’em is all about folding and waiting for that time that comes up every hour or two where you actually have an advantage and you can press it,” he says. “I had a couple of advantages over the group. Number one, I probably cared less. This was the event of the year for them. We make bigger bets every day. There’s more at risk in what happens in Microsoft than I could ever bet on a poker table. Two, I keep a reasonably decent poker face.” A trader who has known him for more than a decade said his talents at the table translate easily to the market: “There are lots of smart people out there. I don’t think all of them have the ability to read the rest of the players as well as David. He can actually see how stocks move on different pieces of news and judge what facts the market seems to be acting on. Then he assesses what analytical edge he has over the other players.”

“I think he’s endangering the franchise—his own franchise. I believe every word he says, but I’d never say it myself. If Lehman failed, how many lawyers would be coming after him?”

He certainly knows what bluffing looks like. In its early days, Greenlight prospered, in part, by identifying a succession of weak financial firms and aggressively shorting them. Delving deep into their books, Einhorn saw, before the market did, just how paltry their hands, which is to say their balance sheets, really were. His shorts on Conseco, CompuCredit, Sirrom Capital, and Resource America—some of the more spectacular corporate flameouts of the late nineties and early aughts—each returned more than 80 percent. Greenlight had bombs, too. It bet against a dot-com-era phenomenon called Chemdex, adding to its short position as the stock soared for no good reason. Finally, Greenlight lost its nerve and covered at about $160 a share, losing 4 percent of the firm’s total capital. Before the end of the year, the stock crashed to a couple bucks.

“We’ve had catastrophes, and that was one,” says Einhorn. “And what we do is we own up to it immediately, we write about it in the quarterly letter. We admit our mistakes so that we have a chance at not repeating them.”

The most recent catastrophe involved a subprime lender called New Century, in which Einhorn held a position dating back to 2002. He even sat on its board of directors, stepping down shortly before the company collapsed in early 2007. Einhorn had been drawn to the company because it had what he considered an advantageous model—rather than convert its loans into securities, as many lenders do, New Century sold its immediately for cash. All it did was originate loans, and in Greenlight’s analysis, that made it safer and more profitable than others in the field. But that distinction failed to make a difference when the subprime market cratered—“If the ship sinks, it doesn’t matter who’s sitting in luxury class,” says a manager of a rival fund—and the wreckage of the company is now in litigation, limiting Einhorn’s ability to talk about it freely. What he does say is that the company began to convert loans into securities and that he joined the board to urge otherwise. In any case, Greenlight seems to have missed a fundamental truth—that the whole sector was headed over a cliff.

The spread of the subprime crisis provided opportunities to recoup those losses. The trigger for Greenlight was an unheralded item that came across the wire in late July: The largest bank in France, BNP Paribas, had frozen its depositors out of their money-market accounts, an event that caused barely a ripple of coverage in the United States. But at the Greenlight office, an alarm went off. “I was thinking to myself that these people are workers in France, they’ve got a money-market account that they’re earning no money on. Their only goal is to have that money available to them whenever they want it; that’s what a money-market account is. You can’t freeze the money market. But when they did that, I was already studying the collateralized-debt obligations and all that other stuff because our short on bond insurer MBIA was beginning to work. The stock was going down. There was pressure building.”

The news convinced Einhorn that a much larger crisis was imminent, and on a Friday afternoon, he called together his analysts and they developed a plan for the weekend—to come up with as comprehensive a list as possible of financial firms with exposure to subprime loans. “We did something we’d never done before. We left on Friday, and by Sunday night, we had a list of 25 financial firms that we wanted to short. Research-wise, we did a lot less work than we usually do when we take a position. There wasn’t time.”

Over the next three days, Greenlight shorted all 25 stocks. “It was what we called the ‘credit basket,’ ” says Einhorn. “A big macro call. One percent of this, one percent of that. No large positions. We were looking for the firms that we thought had the most exposure. Over the next two or three weeks, we kept working on it, closing some shorts, concentrating our positions on the firms that we felt were the most vulnerable. Goldman, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, UBS, Bear Stearns, Lehman, Citigroup—we got them all. They started announcing earnings. We started listening to conference calls, tracking the earnings.”

The earnings conference call is a routine exercise on Wall Street. Typically, firms release their quarterly earnings a few days in advance and then answer the specific queries of analysts during the call. Like many investors, Einhorn finds them a useful check of a firm’s truthfulness, and when he listened to the Lehman call in September, he didn’t like what he heard. “They sounded less honest than the other firms.”

Was that merely a gut feeling? I asked.

“It wasn’t a gut feeling. It’s an experience. It’s when people ask reasonable questions clearly and they get bogus answers back.”

Among other things, Lehman was taking advantage of a new accounting mechanism that allowed it to book revenue based on the declining value of its own debts. In other words, because of the increasingly risky state of Lehman, loans that other firms had made to Lehman had dropped in value, and under the new accounting, Lehman could count this as a gain.

Lehman is not the only firm that employs this trick, but in Einhorn’s view, it was the least transparent about it. “Morgan Stanley announced their quarter and they did the same thing, although they were incredibly explicit about it. ‘We’re fair-valuing our liabilities, it creates a gain for us, here’s the amount of our gain.’ Lehman wouldn’t even tell you the amount of the gain. This is crazy accounting. I don’t know why they put it in. It means that the day before you go bankrupt is the most profitable day in the history of your company because you’ll say all the debt was worthless. You get to call it revenue. And literally they pay bonuses off this, which drives me nuts.” Einhorn almost sounded like he might be getting mad. But he kept his tone at the level of intense bemusement.

In sifting out the worst companies in the basket, Einhorn understood where he could make the most money. “The world just broke apart. On the one side, you had Goldman, which obviously had it right, and Lehman, which said they were like Goldman. And then there was everybody else, who either had it wrong or massively wrong. As you looked, you could see where Goldman had it right, and you couldn’t really see it for Lehman, except they kept repeating it, louder and louder, and the media is going off, story after story about how Lehman got it right, how Lehman’s hedged. It just didn’t make any sense.”

The credit basket went from 25 firms to six. The process wasn’t perfect. Greenlight covered its short on Citigroup just before the stock took a major hit. But before long, the basket was down to two, Lehman and Bear Stearns. And though Bear was the one to go down, Einhorn believes Lehman barely escaped the same fate. “Other than the charismatic value of the leadership and maybe the popularity of the company,” he says, “Lehman’s exposures are worse than Bear’s on an apples-to-apples basis.”

If Einhorn has been the face of the shorts, Callan, then Lehman’s CFO, was the same for the other side. She was a ubiquitous presence on television and in the newspapers, talking up Lehman’s financial health in the midst of the Bear Stearns meltdown. She won praise from, among others, Meredith Whitney, the banking analyst at Oppenheimer & Co., one of the early skeptics in the sector. Callan, Whitney told The Wall Street Journal for that May 17 story, “is going out on a limb to provide more transparency in Lehman’s earnings, business, and strategy. As long as things play out according to her guidance, she will solidify her reputation among investors.”

After Einhorn announced in April that he was shorting Lehman, the firm called Greenlight and asked for a copy of the speech, which he sent over. That led to the call between Callan and Greenlight, right before the Sohn conference. Callan’s position, and the firm’s, was that Einhorn didn’t understand the full complexity of their business and that he was merely seizing on particular aspects of it as evidence of wider problems that didn’t exist. More than that, they saw Einhorn as preying on panic in the market for his own crass financial benefit, at potentially disastrous cost to Lehman shareholders, employees, and the financial system. “Short and distort” was Lehman’s anti-Einhorn rallying cry. It didn’t go unheeded on Wall Street. Bear Stearns had been such a big score for so many short sellers that the SEC is now investigating whether they instigated a run on the bank. In the view of Lehman Brothers, Einhorn was merely keeping the short-selling frenzy going and potentially voiding the whole purpose of the Federal Reserve’s intervention at the time of Bear Stearns’ troubles, which had been to prevent another big firm from toppling into insolvency.

Even some in the hedge-fund community puzzled over what exactly Einhorn was up to. Taking a short position is one thing. But what was the point of being so public about it? Einhorn’s contention that it was “the right thing to do” didn’t compute. Most didn’t want to be on the record even discussing shorts. That’s how touchy the issue is. One hedge-fund manager says that going public with a short position is “a business decision we’d never make. The unwritten code is that you don’t talk about your shorts because it’ll make it hard to get meetings with corporate management, which we need to do our job. Management is scared to death of short sellers.”

“I think he’s endangering the franchise—his own franchise,” says another manager. “I believe every word he says, but I’d never say it myself. If Lehman failed, how many lawyers would be coming after him?”

A hedge-fund analyst who covers the banking sector agrees that Einhorn’s analysis is hard to refute, but believes that “the same is probably true of all the broker-dealers. I don’t know any CFO who’d be willing to give you real numbers for what’s on their balance sheet in this environment.”

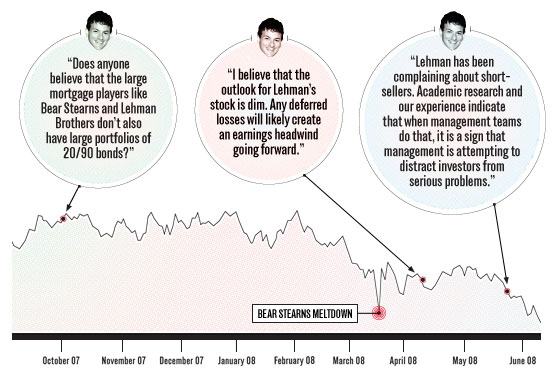

When Einhorn made his first public remarks about Lehman, a passing reference in a speech that was largely about the failure of the rating agencies to keep up with a massive expansion in credit risk, the company’s stock traded at $57 and rallied modestly over the next couple of weeks. When he talked about it again at the Grants conference on April 8, it traded at $43.67, and dropped about three bucks the next day, though it would soon be back over $45. And when he spoke at the Sohn conference on May 21, it had closed that afternoon at $39.56. The next day, it was down just a dollar, or less than 3 percent.

So Einhorn’s Sohn speech didn’t quite match his Allied speech in immediate market impact. But Lehman stock has weakened almost every day since, whipping Wall Street into a frenzy, making Einhorn a lot of money, and rallying what was left of Lehman’s supporters. And the world once again started crashing down on his head. Brokerage analyst Brad Hintz of Sanford C. Bernstein, who used to be the CFO at Lehman, told Business Week that the “concerns of the shorts” are “overdone.” An analyst on CNBC said Einhorn was “inexperienced” and called his research “flimsy.” A senior partner at a buyout firm, though no fan of Lehman’s, summarized one cynical view of Einhorn on the Street: “When a guy stands to profit as much as he does, shorting a company in so precarious a condition that the Fed had just moved in to protect it, well, you have to wonder about his motivation. Yeah, there’s truth to his argument, but now is not the time. Two years ago would’ve been heroic. If he brings down Lehman, the guarantors are going to be me and you the taxpayer.”

His defenders make an equally emphatic argument, insisting that his actions effectively changed the incentives inherent in the system. “What David is doing is highly principled,” says Herb Greenberg, a former financial journalist, now an independent stock researcher, who alerted Einhorn to the possibility that his phone records had been searched by Allied. “This is the way you want the system to work—people saying what they think, on the record, so that people can decide for themselves. This is not Sunday school. It’s the market. It’s a tug of war. It’s when negative opinion is suppressed that bubbles grow.”

It turns out Einhorn was right. At the beginning of last week, Lehman Brothers announced that it had lost $2.8 billion in the second quarter, and that it would be raising $6 billion through an issuance of common stock to shore up its balance sheet. The stock dropped precipitously every day thereafter, and rumors started to circulate about a possible sale, a startling turn of fortune for a company that had only recently been comparing itself to the vaunted Goldman Sachs. In an e-mail analysis, value investor Whitney Tilson credited Einhorn with having made Lehman face facts: “The losses are the losses—Einhorn certainly isn’t causing them. But thanks in large part to his questions, the company is selling assets, deleveraging and raising capital, all of which makes it more likely that the firm lives to fight another day rather than imploding and shaking the world financial system to its core.” On his New York Times DealBook blog, Andrew Ross Sorkin put it more bluntly: “Few people had more reasonable claim to vindication on Monday than David Einhorn.”

Then heads started to roll. On Thursday, Lehman announced the replacements of Callan and the company’s chief operating officer, who had worked with CEO Fuld for more than twenty years (Callan will retain an investment-banking job at the firm). Einhorn refused to apologize, but neither did he gloat. In fact, he chose to exit the stage. He refused to talk about when Greenlight would cover its Lehman shorts, or what he thought about Callan’s losing her CFO job. The truth had been revealed. The story was over. There was nothing more to say.

Some weeks before the Lehman story blew up, Einhorn went to play tennis at the courts at Grand Central. Greenlight has a court reserved one afternoon a week for whoever from the firm can make it, and fairly regularly, that includes Einhorn. It’s one of the few things he does outside work that doesn’t involve his wife and kids. “I’ve got a fantasy-baseball team with my brother,” he says. “But I have to admit, he does all the work.”

He and his colleagues play a goofy, good-natured game in which every halfway decent shot is loudly praised. But they do keep score. When Einhorn fell behind on his serve, you could see him reach back to put a little extra smack on the ball.

At the end of their match that day, as Einhorn left the court, two waiting players, guys who looked like hedge-funders out of central casting, recognized him.

“Hey, you’re…”

“David Einhorn.”

“Yeah, the poker guy.”

Today, his gambling skills are held in higher regard than ever. While his supporters hail him as a brave reformer and his detractors call him a predator, most of Wall Street looks at him as the guy who called Lehman’s bluff and walked away with a giant pot.