One crisp, early-summer morning, MaryAnn and Jimmy Skubus and I are holding hands at a Starbucks—they’d extended their hands and, taking the cue, I grabbed them. MaryAnn says grace, blessing our scone and marble cake, then turns to the subject that’s brought us together. “David is so different from what everyone thinks,” she says. “He’s a special person.” David is David Berkowitz, better known as Son of Sam, and, in one sense, everyone knows that he is out of the ordinary: He’s the most famous serial killer in New York history.But what does MaryAnn mean, David’s special?

I pick at the scone. Jimmy, a big-boned, easygoing ironworker, attacks the marble cake.

“Am I going into this, Jimmy?” MaryAnn asks. She seems on the verge of some big emotion.

“Why not?” he says and shrugs his powerful shoulders.

As far as I can figure out, Son of Sam hasn’t spoken to the press in seven years. Yet reports filter out that he has a new outlook and a new set of friends. And so when MaryAnn introduced herself to me as “a good friend of David’s”—we bumped into each other at the courthouse where David has a legal matter pending—I was encouraged. Perhaps MaryAnn and Jimmy can tell me about the new David.

Unfortunately, at Starbucks, MaryAnn, 48, tall and skinny, seems stalled in her tracks. She’s got this intense look on her face, and an intense outfit. She wears a black motorcycle jacket, black motorcycle boots, and black motorcycle gloves. There’s a pastel-colored band circling her head, a kind of homage, I learned later. The headband makes her think of Jesus’ crown of thorns. She stares at Jimmy. “Oh, Jimmy, these are heavy things,” she says.

Jimmy nods, encouraging her.

“It’s hard to say,” she begins. She leans forward, turns her electric-blue eyes on me, then announces, “I have the call of a prophet upon my life … It’s wild because it’s self-proclaimed. There’s nothing I can do. I cannot escape. The Lord will defend me in it.”

Then she adds, “That’s how I knew about David the minute I saw him.”

“What did you know about David?” I ask stupidly.

At first, MaryAnn explains, David was not a person for her but a number. “The Lord had given me, shot into my spirit and I could never shake it, the number 44,” she explains. Years before she met David, she’d even named her dog 44. “Periodically I would get the number 444, which was like the perfection of the number.” MaryAnn didn’t understand at first, but later the meaning became crystal clear. She says, “It was the identification of David Berkowitz.” Initially, the press called him the “.44-Caliber Killer,” because his six murders were committed with a .44-caliber pistol. Then two years ago, she ran into a guy she knew at the local Shop Rite, a Christian like her. They started talking, and soon he invited her to visit David in prison.

“When David walked in [to the visitors’ room], I knew,” she tells me.

Again, I wonder, “What did you know?”

“There’s nobody bigger than this guy. Oh, my God, this guy is an apostle of the Lord.”

David Berkowitz, the Jewish serial killer, an apostle of Jesus?

“It would be a prophet that would know,” MaryAnn assures me.

Leaving Starbucks, I hand my business card to Jimmy. Later that afternoon, I call MaryAnn. “Jesus is Lord,” MaryAnn answers. She seems very excited to hear from me. There’s apparently been a sign; in MaryAnn’s world, there are no coincidences. Jimmy, she explains, noticed the magazine’s address on my business card: 444 Madison Avenue.

“This is probably the guy we should be working with,” he told MaryAnn. (If that weren’t enough, the Starbucks bill came to $12.44.)

Then MaryAnn asks me if I want to meet David. “Thank you, Lord,” I say aloud after I hang up.

To most New Yorkers, Son of Sam is still the iconic figure of evil. Thirty years ago, he began a reign of terror, killing six and wounding seven over the course of a year. With the city’s newspapers trumpeting each attack, he terrorized New Yorkers as no lone criminal has ever done. (no one is safe from son of sam, said a Post headline at the time.) Sam targeted young female strangers—white, college-bound prizes of the middle class. At times, he seemed to court the city. He believed, as he later put it, that “people were rooting for me.” After nearly three months without an attack, he wrote Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin: “I am still here like a spirit roaming the night. Thirsty, hungry, seldom stopping to rest.”

The city panicked. People turned in relatives, neighbors. Women, alerted that Sam preferred brunettes, dyed their hair or bought wigs. It didn’t matter. Weeks after the letter to Breslin, Sam killed again. The victim was Stacy Moskowitz. “My daughter was blonde,” the victim’s mother, Neysa, lamented. Then, a couple weeks later, in August 1977, he was caught, tripped up by a traffic ticket, a pudgy, 24-year-old postal worker with a boyish face, seventies sideburns, Elvis-ish dark hair, and an eerie, apparently indelible half-smile.

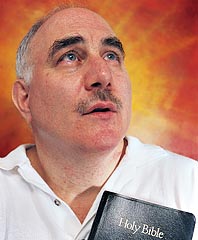

Son of Sam was sentenced to 365 years in prison, which should have kept him out of the public consciousness for several lifetimes. But in prison, an amazing thing happened. The infamous serial killer became a holy man, holier because of his evil past. He’s now at the center of a growing Christian mission. His humility, his piety, his charitable, Christlike heart inspire Christians around the world—one African is even named after Son of Sam. (He’s Kwaku Berkowitz.) Fellow Christians overwhelm him with letters. They pray for him and crave his advice, his spiritual insight, his fatherly guidance. He produces videotapes and journals, gives interviews to Christian radio shows. David—he hates the words “Son of Sam”—works as a pastor, walking the prison halls with a Gideons Bible and a calling from God. He’s battling Satan, he says, his old friend. And David is sure Satan’s afraid of him, because David knows all his tricks. The monster who terrorized New York is now apparently on the road to redemption. “I’m heaven-bound and shouting victory,” he tells Christian audiences.

“How ya doin’?” calls David as he strolls toward us with a little wave. The apostle, I notice, has an accent from the Bronx. MaryAnn and I wait in the visitors’ room of the Sullivan County Correctional Facility, a large tiled room that resembles a high-school cafeteria. David pulls up a chair at our assigned spot, places his aviator-style glasses on the knotty-pine table, a product, by the look of it, of the prison shop. David still has the belly, but he’s middle-aged now—he just turned 53—his face rounder, softer. And he’s balding. The remaining hair is nearly white. Son of Sam looks harmless, like the aging postal worker he might have become.

“I don’t know how long you’re planning to stay,” David immediately tells me. His words are sharp but not the tone. He is wary.

MaryAnn, I know, has already pleaded my case once to David. “When she feels the Lord’s hand, she won’t compromise,” Jimmy had explained to me. Now she intercedes again. “Tell David what’s on your heart,” she instructs me. Dutifully, I begin a rambling disquisition about David’s changed heart, his redemption, I say, using a word MaryAnn likes.

“Oh … okay … okay,” David says, pausing mysteriously between words.

To get through the metal detector, MaryAnn had removed the metal cross from around her neck. But she carried in her red-leather Bible, which she pushes toward David. She tells him to share from Scripture.

“MaryAnn is director of operations,” says David good-naturedly. “I’m glad she didn’t bring her bullhorn.”

And so, at our little prison-made table, Son of Sam starts to lead a Bible-study group. He flips to Romans 15:13. “Now the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, that ye may abound in hope, through the power of the Holy Ghost,” he reads. I extract a few sheets of paper from a pocket along with a half-pencil. David thumbs to Psalm 34:6. It’s the psalm that inspired his conversion, the linchpin moment in the latter-day Son of Sam. David’s conversion story opens in a prison yard twenty years ago with the protagonist in despair: “I had nothing left to lose because I lost everything. I was an utter failure,” he believed.

“Hey, Dave, do you ever read the Bible?” called an inmate, his identity now lost.

“No, I never read it,” David said, and the inmate gave him a Bible.

One night, alone in his cell, David fell upon Psalm 34 and began to pray: “God, you know, I can’t take this anymore.” He prayed and cried and then suddenly, he tells me, “the idea that I could be forgiven entered my life.”

David says the proposition of forgiveness initially troubled him. “I thought, Maybe you’re not forgiven,” he says. “An inner voice said I’ve done too many bad things.” Three years later, in the prison chapel, a pastor read Micah 7, the verses about a God who “delighteth in mercy.”

“It was as if he was talking just to me,” says David. “Right then it just hit me. Something lit up inside me. Inner chains were broken in me. I realized God had forgiven me.”

Once before, shortly after his arrest, David had also declared himself a born-again Christian but soon recanted, deciding he’d been brainwashed. “Was my involvement with these Christians just out of psychological need—a love substitute?” he asked at the time. Such questions no longer trouble him. A God who delights in mercy delights him. “I knew that I knew that I had been forgiven,” says David. “I know that God loves me, really loves me.” For David, conversion was a supernatural event, and it changed his character, he says.

Some audiences rejoiced at the news. For a Christian, consorting with the Devil is not necessarily a liability. Instead, as David learned, it can be a mark of election. David’s admirers seemed to think that the bigger the sin, the better the Christian. What, after all, demonstrates God’s power better than redeeming someone like Son of Sam?

Victims’ families, law enforcement, and civil society in general tend to take a different view. Some evil is unforgivable. Once, in the room where we now sit, a visitor approached David and punched him in the face, a personal attempt at payback. This summer, when David came up for parole (which happens automatically every two years), newspapers checked in with victims’ families. Should Son of Sam be on the streets again? “I’ll kill him,” responded one father. David understands—he declined to even apply for parole this year—and didn’t press charges against his assailant. He wants nothing more, he says, than to apologize to his victims’ families. Several years ago, he wrote to Neysa Moskowitz, mother of his last victim, Stacy, the blonde. Neysa had rarely passed up a chance to tell the press that she loathed David.

“The Lord put it in my heart to reach out to her because Neysa’s suffering a lot,” David says. He wrote to her in September 2000: “I am sorry that I ruined your life and your dreams.” Neysa wrote back. A relationship developed. David even sent her Mother’s Day cards. Eventually David called her from the prison yard. “I started crying and began apologizing,” he says. They talked about Stacy, he says, even shared a few laughs. Later, when a Christian admirer mailed David $20,000, he sent $1,000 to Neysa, which she appreciated. (He says he didn’t keep any of the money.) At one time, Neysa and David even planned to meet at the prison; it was going to be filmed for TV. Neysa says she wanted information about the murder of her daughter. David backed out. “I couldn’t in my heart. It would be a circus. I had personal things to share I didn’t want to be used,” he says. Soon thereafter, the relationship fell apart. “Neysa’s forgiveness was withdrawn,” David tells me glumly. “She’s back to hating me.”

David returned to the more reliable forgiveness of a magnanimous God. “So much has happened in my life, so much healing, so much deliverance, so much forgiveness, not from people but from God,” David has explained. He doesn’t really like to think about his crimes anymore. “Too painful.” A grimace sweeps across his face. Plus the past is mostly “a blur.” It seems to David that God has tossed the distressing details of his crimes into the sea of forgetfulness, along with his sins. For David, it’s time to move on. “I can’t undo what was done. It’s 30 years ago. Enough already,” he tells me.

There was a time when David could think of little besides his crimes. Shortly after his arrest in 1977, he confessed to all six murders. For an accused killer, he was unusually talkative. Effortlessly, almost proudly, he provided chilling details about each attack. (“[Stacy] and her date started to kiss passionately,” he wrote. “At this time, I too, was sexually aroused … They went back to the car … I had my gun out, aimed at the middle of Stacy’s head and fired … I didn’t even know she was shot because she didn’t say anything nor did she move.”) What troubled David, and what he couldn’t explain, was why he committed the crimes. “I can’t figure out what made me kill those poor people,” said David, a surprisingly reflective monster. At times, David seemed to crave not only an explanation of his motives but a theory of himself. Soon enough, competing schools emerged to do the job, and David, like an impressionable seeker from the seventies, tried one after the other.

At first he sided with those who believed him insane. Lawrence Klausner, a novelist who wrote Son of Sam in 1987, partly based on David’s prison diaries, proposed that he lived in a psychotic fantasy world. It was easy to believe. Months before his killing spree, David, recently back from the Army and on his own for the first time, wrote to his father in Florida: “Dad the world is getting dark now. I can feel it more and more. You wouldn’t believe how much some people hate me.” Another letter to his father was ebullient but also disturbing. “I feel like a saint sometimes. I guess I’m kind of one.” In his prison diaries, David seems completely mad at moments. He reported that a dog spoke to him, channeling a 6,000-year-old man named Sam whom he sometimes identified with Sam Carr, a neighbor and dog owner. “He told me [to kill] through his dog, as he usually does,” David wrote. He worried that his condition would worsen. “I may, one day, evolve into a humanoid or demon in a more complete state,” he said. Three of four court-appointed psychiatrists didn’t hesitate; they found him unfit to stand trial.

A fourth, however, took a different view. “His delusions were manufactured,” wrote Dr. David Abrahamsen. (“Sometimes a dog is just a dog,” quipped the doctor.) It was a view that David, too, soon found compelling. From prison, he wrote to Abrahamsen, a professor, psychiatrist, and researcher affiliated with Columbia, “I guess you see me as I really am—an animal and unhuman.” Suddenly, David had only disdain for the doctors who fell for what he now called his ruse.

“All I had to do was slide ‘Sam Carr’ and the ‘demons’ into the conversation,” wrote David about his relationship with another court-appointed psychiatrist. “Why he would practically be wiping the tears from my eyes and comforting me. Goodness what a nice man he was.”

In Abrahamsen’s view, David was sane. He was also grandiose, hysterical, and profoundly troubled. And the root of the trouble was adoption. David Richard Berkowitz was born Richard David Falco. At a few days old, he was adopted by Pearl and Nathan Berkowitz, a modest, childless Jewish couple who lived in a one-bedroom Bronx apartment. David’s hardworking father, who owned a hardware store, was often absent. But Pearl was doting. “I loved her very much,” David told Abrahamsen during an interview, sobbing. She died of cancer when David was 14. “After Mother’s death,” he said, “I lost the capacity to love.”

In his 1985 book Confessions of Son of Sam, Abrahamsen argues that adoption was the initial wound. “He’d lost the love that should have been given him,” he concluded. The death of his mother was a second, again by a woman. In 1975, the year before the shootings began, David’s feelings of abandonment intensified. He launched a “personal hunt” for his real mother. He found Betty Falco in Queens and slipped a Mother’s Day card in her mailbox. Betty, once an aspiring Broadway dancer, was ecstatic at the reunion and welcomed “Richie,” as she insisted on calling David, into her life. David, too, had high hopes. Soon, though, they collapsed. He met his half-sister, the child Betty hadn’t given away. “I first realized I was an accident, a mistake, never meant to be born—unwanted,” he wrote to Abrahamsen. David learned he was the by-product of Betty’s longtime affair with a married man.

He continued to visit Betty every couple months, acting the part, as he put it, of “Richie nice guy.” Inside, though, something else stirred. “I was filled with anger and rage toward Betty,” he told Abrahamsen. “I was getting a very powerful urge to kill most of my ‘natural’ family.” A few months later, Son of Sam began hunting young women. “I want to be a lover to women, but I want to destroy them too,” David wrote. “Especially women who dance. Them I hate. I hate their sensuality, their moral laxity. I’m no saint myself but I blame them for everything.” In Abrahamsen’s view, David’s spree was revenge against women, especially Betty. The dogs, the demons, were metaphors for the violence within. It was no coincidence that he hunted in lover’s lanes, targeting young women making out in parked cars. David wrote, “My mother Betty was sitting in those parked cars with [my father].”

David liked communicating with Abrahamsen, which he sometimes thought of as talking to God. Eventually, though, he soured on Abrahamsen and on the good doctor’s interpretation. “He had a mold that he wanted to fit me in and would do what he could to make me fit that mold,” David decided. David shifted his interpretive allegiance to Maury Terry, who minced few words when it came to Abrahamsen. “Yeah, everything’s the fault of the mother,” Terry says. “You know, it’s just bullshit. Abrahamsen was so full of himself he got right to the brink of getting the truth and then stopped.”

In his 1987 book The Ultimate Evil, Terry, a former business journalist for IBM, proposed a bold new theory of David’s crimes, and also of his character. In Terry’s view, David’s fundamental flaw wasn’t insanity or emotional instability but an abiding gullibility. “Berkowitz was susceptible to any line of shit,” says Terry. His failing, the one that underpinned all others, was an intense loneliness, a vulnerability. David had once inventoried his problems: “A series of rotten jobs, to a rotten social life and a horrifying feeling of becoming an old bachelor or a dirty old man. I had no woman in my life … I felt like worthless shit.” He “thirsted,” as he put it, for normal relationships with people. One night, outside his Bronx building, he ran into Michael Carr, son of Sam Carr, the neighbor whose dog did or didn’t speak to David. Michael Carr invited David to a nearby park, which Terry says was a meeting place for a Westchester affiliate of a satanic network called the Process Church of the Final Judgment.

David began attending meetings in the woods. “Before long he was cutting prints in his finger and pledging to Lucifer,” says Terry. Or to Samhain, the Druid devil, and a source of the name Son of Sam. The group got into small-time arson and animal sacrifices, and then it escalated. Terry says the cult was behind the Son of Sam killings. There’s long been circumstantial evidence that David didn’t act alone. Six police sketches based on eyewitness accounts look dramatically dissimilar (and one closely resembles Michael Carr’s brother, John). The most compelling corroboration, though, comes, as usual, from David. In 1993, Terry interviewed him in prison for Inside Edition. On camera, a nodding, penitent David explains, “The killings were another sacrifice to our gods, bunch of scumbags that they were.” Later, he explained, “We made a pact, maybe with the devil, but also with each other … We were going to go all the way with this thing. We’re soldiers of Satan now. I was just too far in, too loyal, too much playing the role of the soldier and trying to please people.” The killings, he told Terry, were a group effort. “I did not pull the trigger on every single one of them,” David said. He didn’t pull the trigger on Stacy, he told Terry. He killed three people, though he was always at the scene. Others dispute the conspiracy theory. Abrahamsen, for one, considered it hogwash. And Neysa, whatever forgiveness she may have once expressed, blames David alone. She has a letter from him that settles the matter for her. “I hope that one day you will forgive me for taking your daughter’s life,” he wrote.

And yet, enough suspicious coincidence swirls around the case to give pause. Soon after David’s arrest, John and Michael Carr both died mysterious deaths, one an unsolved murder, the other possibly a suicide. Even the Queens district attorney at the time believed David didn’t act alone. In talking with me, David doesn’t deny his involvement with the Carr brothers. Officially, a police investigation is still open, says Terry.

“I was expecting to go to hell,” David said later about his spree. That didn’t put him off. “I’ll be with my friends,” he thought. But then, after his arrest, he learned that their friendship only went so far. “They completely abandoned me,” he said.

In the prison visiting room, David, MaryAnn, and I huddle over the Bible. David and his Christian friends, I know by now, are no ordinary churchgoers. They’re right-thinking, intolerant prayer warriors for whom churches are too tame; MaryAnn left hers a decade ago. “I’m not some dorky bake-sale Christian,” she let me know. “I don’t quote the Scripture, I live it.” For them, the world described in the Bible is vibrant and alive, as real as the world they live in. “You’re like the early disciples,” I once said to MaryAnn, which pleased her.

David locates a passage. A chubby finger pokes at each word as he reads it. It’s a tale of demon possession from Mark.

MaryAnn prods him, “Go further.”

“When I read this a long time ago, the Lord said to me, ‘This is you,’ and I saw that this could be the story of my life,” he says.

For David, it seems the Bible is the ultimate explanatory adventure, a last attempt to name the demon. David doesn’t take these verses from Mark as a parable of how people get caught in a web of sin. For David, the Bible is a detailed, precise, almost journalistic account of the struggle between fierce combatants, God and the Devil.

Reading the Bible, David finally discovers why he killed those poor people.

“There is no doubt in my mind that a demon has been living in me since birth,” he says. “As a child, I was fascinated with suicide. I thought about throwing myself in front of cars. I was out of control.”

As a child, David pulled apart and burned his toy soldiers, sometimes throwing them out the window at people in the street below. “I was obsessed with Rosemary’s Baby,” he says. “I felt like it was speaking directly to me. I stayed in my closet. I ‘ran from the light into darkness,’ as the Bible says.”

Everything now makes sense. His longings, his isolation, and his serial disappointments with girls were real. They were also, he once described, “a spell to turn people away from me and create a situation of isolation, loneliness, and personal frustration, as part of [the Devil’s] master plan.” The speaking dog was real, too, David tells me. He believed that dogs really did communicate with him, though now he knows it was another satanic trick.

I set down my pencil. I’m not sure what to make of the return of demons and talking dogs. David, always attuned to his interlocutor, is sensitive to my secular doubts. “If people don’t have a clue about spiritual things, they’ll say, ‘Well, this guy is nuts,’ ” is how David explains it.

David fixes me with blue eyes, close-set in a big oval head. “The Devil can manifest psychologically,” he says serenely. “Looking at someone controlled by an evil spirit, you’d think that person’s crazy … It’s all hard to explain.” There’s a shrug to his tone, as if to say, make of it what you will.

“The demons are real. I saw them, felt their presence, and I heard them. You get into a state that is so far gone your own personality is dissolved,” he’d once earnestly explained, “and you take on these demonic entities … It was like another person was in me … doing a lot of directing. I struggled, but things became overwhelming. I lost my sense of myself. I was taken over by something else, another personality.”

To David’s Christian circle, this is not incredible; it’s heartening. David’s dark past ushers them into the thick of a miracle, God’s mercy. To them, it’s as if he’s a figure out of the Bible, a familiar to its intense moral struggles, its miracles, its direct, communicative God. And right here in the Catskills, a short drive away.

In turn, his Christian friends celebrate David, elevate him. MaryAnn tells me that he is a modern-day Paul, the murderer who became an apostle. “That’s David,” says MaryAnn. “He lives by the Scripture,” says one Christian former law-enforcement officer. “He’s Jesus-like,” says another Christian friend, a former Jew, referring to David’s pared-down lifestyle. “He has an advantage,” I was told. “He’s away from all the distractions.” Incarceration, in this view, is a symbol: It stands for Christian suffering. “The walk of a Christian is to the cross,” MaryAnn tells me. “That’s the spirit of David.”

David has a long scar on his neck where an inmate at Attica slit his throat. MaryAnn reaches a hand to lift his collar. She wants to show me the scar, evidence of his trials. David flinches. He doesn’t want to draw attention to his past. Instead, he returns to the leather-covered Bible—MaryAnn covers her Bibles, the only books in her house, with old motorcycle jackets. He pages through, arriving at Acts 9. It is about the conversion of Saul—who, like David, was a Jew—to Paul the Christian. Saul was the persecutor of Christians; Paul the apostle of Christ. Next to this passage, I notice that MaryAnn has written, “DB’s testimony.”

“Paul … had to forget those past things and press on to the glorious future with God,” David believes, “and I have to do the same.”

In the visitors’ room, MaryAnn begins to quietly sing a hymn. She’s a musician with a beautiful voice and writes her own Christian songs. (She wrote one about David, rhyming “Son of Sam” with “the Great I Am.”) David sings along for a minute, then stops, perhaps embarrassed in front of me. He blushes. There’s a silence, and then MaryAnn says to David, “There are men that God raises up, and you’re one of them.” To me, she says, “God will build a church on David’s back.”

David rapidly blinks his eyes. “Okay … okay,” he says. It’s difficult to know what he’s thinking. Then he raises his palms, flapping them as if shooing away the subject.

“I’m a servant,” he says, which, MaryAnn assures me, is what an apostle would say.

People think I’m a figurehead,” says Berkowitz, “like Manson or something. He’s supposed to have groupies. I would hate that.”

“David is not going to tell you that he has the high calling of an apostle,” she says.

“I see myself as a humble servant, not as a big shot,” he reiterates. “People think I’m a figurehead … like Manson or something. He’s supposed to have groupies. I would hate that. I wouldn’t want that. I’m not the fanatic people have in mind.”

“I really believe,” MaryAnn tells me. “It’s not even a belief. I know, even though David’s in prison, he was sent to us. We waited on him.”

In letters to me, David wants to make sure I don’t misunderstand. In contrast to his mild presence, his letters are self-assured, assertive, formal. He’s no longer in the confession business. “There are many things I no longer wish to discuss,” he writes. “I kept telling MaryAnn no, that I wasn’t ready [to be interviewed], but she was throwing a tantrum, stomping her feet and even shedding tears. I just moved into a different cell the day before and I was so tired that I capitulated to her request.” He wants me to know that MaryAnn has him wrong. “I am not in agreement with MaryAnn’s assessment that I am some kind of ‘apostle,’ ” he writes in a bureaucratic tone. “I wish to be a servant to others, to help whosoever I can and give people encouragement and hope.”

In prison, David tells me he’s engaged in active spiritual warfare. I’d like to hear more, but with me, he will only go so far. Seven years ago, however, he sat down with a 22-year-old Columbia journalism student named Lisa Singh, who had written him a letter. David sensed the hand of God in her interest and invited her to prison. Lisa included portions of their conversations in a Penthouse article, but most of the twenty hours of interviews remain unpublished; she provided tapes to New York. With Lisa, David seemed to feel freer to express himself, or perhaps he was simply more optimistic at the time. “I personally feel that God is calling me today to fulfill some kind of purpose,” he told Lisa, “that he has some job that he wants done. God is calling me to be a prophetic voice to this nation, to people in general.” God, he senses, counts on him to combat the Devil. David is sure he’s up to the task. “I feel that Satan is very afraid of me because he knows I know so much about him from my own experiences,” he told Lisa. David is quick to sniff out Satan’s influence. The Devil lures kids down dangerous paths and also (still) targets David personally. “Strangers who lash out against me, ‘Oh, he hasn’t changed,’ ” said David. “That’s all part of the battle.” So was Spike Lee’s 1999 movie, Summer of Sam, which spotlighted David’s past. “I feel that the movie is purposely being designed to damage my Christian testimony,” David told Lisa.

Fortunately for David, he lately has means at his disposal to counterattack. He has, by now, access to a modest media empire to spread his message. The key to his reach is his Christian celebrity, which piggybacks on his criminal celebrity and which began about a decade ago. In 1997, Pat Robertson’s 700 Club, which appears on the Christian Broadcasting Network, interviewed David. Robertson praised him, citing David as proof that the Devil is real. The word was out; fundamentalist churches found David. A tiny Evangelical church out of San Diego—it calls itself House Upon the Rock, though it doesn’t have a physical location—hosted “The Official Home Page of David Berkowitz.” That site became forgivenforlife.com and was transferred to Morningstar Communications, a small New York literary agency, which posted David’s near-daily journals back to 1998.

The journals, Christian reflections on everything from 9/11 to prayer in prison, were a turning point in his life, David says. Suddenly he was in communication with an audience. One reader was Darrell Scott, a Christian, whose daughter Rachel, also a Christian, was murdered at Columbine. Scott read in the journals how Rachel’s story encouraged David. Scott traveled to Sullivan County Correctional—“David Berkowitz radiated the life of love of Jesus Christ,” Scott writes—and they became friends.

With the help of another friend, Chuck Cohen, a fellow Jew who is now a fellow Christian, David soon made a Christian video—“Society wrote him off as hopeless … but God had other plans …” David passed me Chuck’s phone number, and I left a message. Chuck called back almost immediately. “My answering machine,” Chuck informed me, “hasn’t worked in months,” which he saw as a powerful sign. (I’d become accustomed to signs. MaryAnn mentioned shopping for an amplifier. The brand name, she said, was Fishman.) At his compact East Side apartment, Chuck reviewed his sinful past, though in his case, the principal sin appears to have been failure to succeed. Chuck, an Ivy Leaguer, was a stockbroker who couldn’t earn a living. (These days, he delivers lost luggage and invests on the side along biblical guidelines. Chuck, sure the end of time is fast approaching, is into gold.) One day, a Christian friend laid his hands on Chuck and his wife. The Holy Spirit entered them, though it took faster for his wife. “She’s already talking in tongues,” he complained to the friend. (Later, talking in tongues came to Chuck too. It’s not difficult, he told me, and gave a little demonstration.) Once converted, Chuck set out to bring other Jews to Jesus. He set up a table outside Zabar’s, and prayed for a celebrity Jew to convert. Woody Allen, he hoped.

“Instead,” says Chuck’s wife, “God chose David to be that famous person.”

The video Chuck helped produce in 1998, Son of Hope, was another turning point for David. In it, he preaches, jabbing a finger in the air and shouting, “I was the Son of Sam, now I’m the son of hope.” Ministers write David “praise reports,” thanking him for his testimony, which they assure him impresses their troubled teens.

David’s Christian fame crossed over in 1999. That was the year David’s past, repurposed as part of God’s plan, attracted Larry King, who did an hour-long interview from prison. The attention snowballed. Other big Christian groups lined up: Trinity Broadcasting Network and, in 2004, Focus on the Family, which sells a CD of its interview with David.

As word of David’s testimony spread, he was also working with African ministers, sending Bibles. And ordinary Christians increasingly sought him out.

The letters pour in. David receives five, ten, sometimes more, a day. People write that they’re praying for unforgiving victims’ families to get over their bitterness. And they write of their own troubles, as if this serial killer were the one person in the world who could understand their loneliness, their disappointments. Some identify with David. “I wanted and planned to kill my ex-boyfriend,” wrote one young woman, whose letter from David apparently pulled her from the brink. David grew especially close to one troubled 17-year-old from Long Island. “Hey Berkoman!” he wrote, then told David that he was “insanely depressed … I can’t stand life any longer.” He wanted David to pray for him. “I don’t care what you’ve done in your past,” he wrote, “I think of you as a dad … you are like the best role model ever! … When I pray for you, I feel loved … I want a life like you are living today.”

It’s mid-afternoon, the fourth hour of our visit, and the visitors’ room at Sullivan Correctional is nearly empty. In the center of our little table, MaryAnn has stacked eighteen single dollar bills. “Make sure David gets fed,” Jimmy had instructed. He had in mind the vending machines lined up in the back of the room. Food has always been a way to David’s heart. Prisoners aren’t permitted to touch money, so MaryAnn urges me to buy David some lunch.

We walk shoulder to shoulder toward the thicket of vending machines. David, paunchy and bald, wears a not-quite-clean white polo shirt tucked into bright-green, elastic-waist pants, and spotless white sneakers. He looks like a middle-aged civil servant ready for retirement, the uneventful future he sometimes imagines for himself if, as he puts it, “all this hadn’t happened.” I slip money in a machine. David delights in all the choices. There’s a machine with flavored waters. “They didn’t have this before,” he says. He selects a Nathan’s hot dog, and breaks into a smile. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen his perp-walk photo by now, the one with that unnerving smile. I wonder how it could have escaped me: Son of Sam has dimples.

At our table, David eats his hot dog, gripping it with those murderous hands (the thought never disappears). Is the new version the sincere one, as his religious friends insist? “A Christian can tell,” Chuck assures me. Or does Sam’s appetite for the spree lurk inside? Is Richie still controlling the grudge within? There is, in David’s life, this disturbing symmetry: Once he was Satan’s devoted soldier, and now he’s a celebrated man of God. Who is he, really, beneath the goofy postman’s grin? When I raise the topic, David nods indifferently, and, as a holy man should, offers a Bible verse. “And some believed the things which were spoken, and some believed not,” he reads.

David says that sometimes he imagines a life outside of prison. “Everyone does,” he says. If he ever gets out, David’s Christian friends see him running a church. “He has the ability to pastor,” says Rich Delfino of New Jersey, an ex–sheriff’s deputy and ex–drug addict who is David’s Bible-study partner. (“There’s never a time I haven’t learned something scripturally from David,” he says.)

David, though, can’t see himself at the head of a church. He’s already MaryAnn and Jimmy’s pastor. And he’s the inmate pastor, which he finds exhausting. “Guys are very needy in here,” David says. Plus, he sometimes works as a peer counselor in the mental-health unit, a $2-a-day job that he also thinks of as part of his ministry. “I’m gentle with guys,” he says. “I’m a big brother, a helper. I see myself as a caregiver.”

When he imagines life on the outside, David tells me he thinks of becoming an Evangelist, a minister traveling to schools and prisons. He could reach out to kids, though the thought of traveling freely must be an enticement, too.

“But God had another plan for me,” David says softly, cutting off the thought.

To leave prison, he tells me, “God will have to do a miracle.” Perhaps the Lord himself will preside over David’s release. “Suppose the Old and New Testaments, and all that is written therein is true?” David asked me. If so, then there is the Rapture to think about, the foretold moment when God will take his chosen home. David sometimes imagines the day that God plucks him from his elastic-waist prison greens. “Jesus is going to come and take his people out of the world,” David told Lisa. “One day, that trumpet is going to sound and we’re going to be gone.”

In the meantime, and perhaps for the rest of his life, God’s special servant experiences little beyond prison life, which David lets me know is depressing. Jesus may have improved David’s character, but a stable mood is still a struggle. He’s not on medication or in therapy, he says. Yet bouts of sadness, crying spells, and hopelessness sometimes beset him. “Prison is crushing, oppressive. There’s anger and disappointment, broken lives,” he tells me. “Every day is a challenge. To get up in the morning and see the bars … Sometimes I can’t get out of bed.”

It’s striking, after a few hours, to hear David speak this way. Christian talk usually conforms to set themes: pitched battles, God’s warming love, triumphal futures. Despair is preamble. Then comes Christ, and worlds, and moods, are remade. Yet sitting here, his hot dog gone, David sounds sad. I ask about his daily satisfactions.

David thinks a moment. “I love nature,” he offers.

It seems a strange thing to say. I look around. It’s the view from inside a concrete mixer. “I am an avid birdwatcher,” he persists in a quiet tone. From his cell window, David says, he watches sparrows and crows splashing in puddles in the prison yard. Sometimes, geese fly overhead. He likes that. “I saw a deer,” he says.

Nature may break the monotony, but for David, happiness, earthly happiness, is a thing of the past. The very thought of it takes him back. As a prison guard looks on, David’s mind drifts into the past, to racing with the neighborhood kids to a Yankees game. “My mom packed a bag lunch,” he tells me. He had a three-speed English Racer on which he sometimes spent entire days. “I miss my dad,” David says abruptly. “I’d love to be leading a normal life.”

David is lonely, though not as lonely as he was. With Jesus, everything is possible, a new future, a different past, even the admiration of others. Once he’d prayed, “Please give me a reason for living.” The Lord came through. “Without Jesus,” he tells me, “I wouldn’t have survived. Because of Jesus, my life is not a waste.”

Our time is up. Visiting hours are over. David spots a guard approaching and, ever attentive to the rules, rises preemptively. He offers me a brotherly hug. MaryAnn and I turn to go. An indulgent guard allows David to linger a moment longer.

“Where do you go now?” I call.

“To hell,” David says, and smiles. That smile.

Additional reporting by Ariel Brewster, Meghann Farnsworth, Matt Stevenson, and Merry Zide.