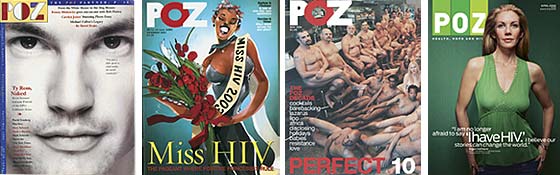

In March 1994, a couple of months before the Times’ announcement that Regan Somers Hofmann, the 26-year-old daughter of David Hofmann of Pennington, New Jersey, and Nancy Hofmann of Princeton, New Jersey, was married to a son of a Chase Manhattan vice-president in an Episcopal ceremony, a quite sick 35-year-old with AIDS named Sean Strub announced the launch of a bi-monthly magazine for people with HIV called Poz. He’d been running a faxed newsletter of HIV information—he’d noticed that the people who had the best information were ones who were living longer—and sold his life-insurance policy in order to start Poz. The magazine’s glossy, graphical urgency set out to celebrate the fact that people were still living with it, coping with it in some way, thirteen years into a plague that was killing a generation of gay men.

In the first issue, a writer profiled the HIV-positive grandson of Barry Goldwater and wrote about having sex with him. It was a magazine that could not have been more of a product of ACT UP and Tina Brown’s Vanity Fair. “The magazine is being done as a business,” Strub assured a reporter at the time, “but it’s unlikely that it will break even in my lifetime.” A trade publication noted wryly that Poz might have some problems with renewals given that its entire subscriber base had a fatal illness.

Not that any of this would have had a particular impact on Hofmann—and why should it? She’d grown up in the era of the AIDS ribbon, Pedro on The Real World, and condom-on-the-banana demonstrations to incoming freshmen. Her thoughts were much more on the fact that she’d left her job in advertising to figure out how to write for a living. She and her husband, who’d also worked in advertising, moved to Atlanta because it was pleasant and close to horses—she’d grown up riding Thoroughbreds—and she could work on her novel there. Soon she and some friends started an alternative magazine called Poets, Artists & Madmen. They published poems, fiction, and record reviews and were profiled in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. (She said she’d “rather have psychic income” than make “bazillions of dollars.”) She and her husband had their problems, though. They lasted only eleven months. She started dating someone new. She burned out on the magazine after two years, and her partners bought her out. That was in 1996. One day, “I had a swollen lymph gland, and I went to the doctor,” she says. She took an HIV test, which came back positive. “They basically gave me a year to live.”

But thanks to the protease inhibitors that happened to be introduced that year, she’s still alive. And this January, she was hired as editor-in-chief of Poz.

It’s not as easy for a magazine to adapt as it is for a virus. HIV isn’t just a gay men’s health crisis anymore: 27 percent of those infected in the U.S. are women; worldwide, it’s closer to 50 percent. It’s increasingly a crisis for poor people, African-Americans. (It’s not that well-educated white gay men aren’t still getting infected, but to the extent that drugs make the virus “manageable,” it tends to be even more manageable for them.) “I would say the magazine always aspired to represent the entire epidemic,” says Walter Armstrong, who had worked there since 1996 and later became editor-in-chief. “But since we had a mostly gay staff, we were maybe more successful at breaking stories that were more relevant to gay men. We tried to do what we could in terms of finding writers and stories outside of our immediate backyard.”

One of those writers was Hofmann, who’d been secretly corresponding with the magazine. After breaking up with the man who’d infected her, believing him when he said he didn’t know he’d had it, she moved back to the fields of New Jersey. “I sort of put my editorial career on hold. I took some time and just worked with horses. I was just trying to gather my wits and gather my health; I didn’t quite know what was going to happen,” she says. “I was on medication from the very beginning, and I’ve tolerated it, and I’ve always been thankfully healthy.” Her doctor put her in touch with a support group. They were all gay men. She’d started subscribing to Poz, which came in a plain purple wrapper. It was, she says, her “lifeline.”

Hofmann picked me up from the Raritan stop on the New Jersey Transit rail line in a growling metallic Mustang. Raritan is something well beyond suburbia. The American Legion has taken over the old pitch-roofed train station, complete with a box “for deposit of used and worn flags.” Next door is a place that refills propane tanks. Hofmann is elegant in a Hamptons-y way in her big sunglasses and skinny, distressed jeans. She looks sporty and vital, and drives too fast along the two-lane country roads that take us to the farm where she lives, her Cobra radar detector chirping occasionally as she makes fun of the nouveau golf-course communities with their sprawling faux châteaux.

Until recently, she hadn’t even told most people in her life she was positive. “I didn’t want them to use it against me,” she says. She’d been working for New Jersey Life, a house-and-garden monthly, and writing occasional pieces about things like Argentine polo players for Departures when Armstrong approached her about becoming the managing editor of Poz. “I wasn’t ready because I was still … I don’t think I had forgiven myself for getting it,” she says. Still, she was willing to write an anonymous column for Poz; the idea was that she’d disclose her status to one person each time, and perhaps reveal who she was in the end. Her first piece was about worrying whether the drugs were affecting her body in a way that would give her away.

“It was very unusual to have someone writing anonymously, since the whole idea of the magazine was in coming out,” says her then-editor, Tim Murphy. “She comes from very Mayberry, small-town USA. She was like an interloper: She hears the things that regular people hear about aids. She wrote this great column where they’re on the veranda of the country club or something and someone says, ‘Isn’t it great that AIDS targets the people that should die anyway?’ ”

Her parents knew, and her sister, but not too many other people did. And she was terrified that they would. As she wrote in an essay in this month’s issue of Vogue, when people inquired as to how she dropped from size 8 to size 4 thanks to the appetite-killing and fat-redistributing properties of her meds, she’d joke about her diet of stress and caffeine, while worrying about not being “healthy skinny.” Still, the closet wasn’t so bad. “I think that one of the things that helped me was that I was able to maintain this normal lifestyle and this perception of myself as a normal person,” Hofmann says. “And the fact that I didn’t tell people was very reassuring, to just be treated as if I were perfectly healthy, because I was for all intents and purposes.” Except for things like when a man she’d started seeing changed his phone number after she told him. Or when her gynecologist refused to even discuss pregnancy with her, even though, if properly monitored, she’d have only a 2 percent chance of passing it along. We’re sitting in a bar near her house, a ski-lodge-like place with plastic flowers and NASCAR flags that hosts line dancing on Tuesday night. When the rather severe-looking waitress comes over to get our orders of fried cheese sticks and local microbrews, Hofmann seems to be thinking about whether she knows. Did she read the piece in the Times about her new job? Does she read Vogue?

Her coming to Poz was more of a personal journey than a career move. Before she could help destigmatize the disease, she had to stop hating herself for having it. “I had always been very careful,” she says. “I had volunteered for Planned Parenthood when I was in high school, I requested that people get tested before I slept with them on occasion. But by the mid-nineties, I’d never heard of a single heterosexual person getting the disease, so I honestly didn’t think I was really at risk. I let down my guard, I was human.” She says she and her boyfriend had unprotected sex only twice. “He really was a guy that I would bring home to Mom and Dad,” she says. “It’s not like, ‘It happened when I was on a drug binge in Brazil for four weeks,’ you know?”

“He really was a guy that I would bring home to mom and dad.It’s not like, ‘it happened when I was on a drug binge in Brazil for four weeks,’ you know?”

Of course, statistically, it’s impossible to argue that she’s the New Face of AIDS—even she’ll admit that. “It’s not that everybody in America who’s getting the disease is like me,” she says. “It’s the Latino community, it’s the African-American community disproportionately, and it’s the aging population. That’s what’s really crazy—they are postmenopausal, virgins when they got married; the men are on Viagra. These retirement communities that people go into sometimes, it’s like a fraternity house. It’s crazy. The infection rates of people over 50 are comparable to those for people under 24.”

The nice prep-school girl from Princeton isn’t quite sure how to handle being a symbol of something—she’s by nature not an activist. But she’s learning.

A year ago, Strub sold Poz to a new company called CDM, which plans to launch other magazines and Websites for different illnesses. Armstrong left soon afterward and recommended Hofmann for the job. When she took it, she told the publisher of New Jersey Life that she was editing a “health magazine.” When the piece came out in the Times, her boss’s reaction made her wish she’d told her seven years before. She’s not the epidemic’s first Waspy spokeswoman: Think of Mary Fisher, who made a speech at the 1992 Republican convention, urging compassion. And there’s a reason why Vogue published that essay.

And now that she’s taken this step, even appearing on the cover of her own magazine, Hofmann wonders whether she’ll still have control of her life. “My PR firm and my boss want me to be a certain way … ” she says. She doesn’t want our photographers in her home—she lives in a barn that’s heated by a wood-burning stove with sheepskin rugs on the floor and a view of a scrubby field that’s home to five horses and an aged Shetland pony. When we go to the bar, she asks that I not mention the name. “I’ve never been a public person,” she says. “I’m just trying to keep a place where I’m safe and off the radar.”

And she certainly doesn’t want to talk about the man who infected her, who died in 2004. “Maybe because some journalist’s reaction would be to twist it into some titillating tale of I don’t know what, but trying to make it less about the issues and more about my particular story,” she says. And she has a point, of course: CDM hired her because she had the experience to edit a magazine and expand Poz.com. It’s hardly even available on the newsstands anymore; almost all of its 115,000 copies are given away in clinics.

It can’t be the magazine Strub started anymore. “There were certain kinds of stories that we had access to before they became sort of well known,” says Armstrong. “Because we were either living them or we had our ear to the ground in the community. Like the barebacking story, which was probably the most publicized cover story we ever had.” “Boys Who Bareback,” in February 1999, was certainly buzzy: An HIV-positive escort and porn star named Tony Valenzuela was profiled sympathetically (and pictured, gorgeous and naked, leading a horse) by Strub’s business partner Stephen Gendin, who died a year later of aids. An accompanying piece went to a barebacking party and quoted a “gift-giver” (a positive person who intentionally infects a negative person). There was a safer-barebacking sidebar. And though in no way did the magazine recommend the practice, many in the aids community still blame the magazine for somehow legitimizing it.

When our photo department called for the cover to be included in the timeline that precedes this article, Hofmann called back immediately, worrying that it was for this profile—that the “boldness” of that era would reflect poorly on her more inclusive magazine for women and “teenagers in Ohio.” “Everyone just takes the disease back to that—gay men are wild and promiscuous. That’s why we have the stigma. It’s such a tiny part of the disease, and of gay men,” she says.

“We’re worlds away from that now. We’re not a gay-lifestyle magazine.” Next: A Biography of AIDS in New York

RELATED STORY:

AIDS in New York: A 25-Year Biography