It isn’t quite Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik, but on a Tuesday afternoon in the 2 Penn Plaza offices of ABC Radio, two titans of clashing ideologies come face to face. Fresh off his daily one-hour ESPN broadcast with former SportsCenter co-anchor and longtime pal Dan Patrick, Keith Olbermann spies a familiar figure settling into Studio B for his afternoon shift. Olbermann, his anchor-issue trench coat tucked under an arm, opens the door and thrusts a hand toward Sean Hannity.

“Mr. Hannity, good to see you, sir,” says Olbermann.

Off-camera Olbermann, it turns out, is a lot like on-camera Olbermann. The gray pin-striped suit is perfectly crisp. The basso profundo booms. The outsize ego and acid tone ooze from him. It’s unclear whether the mannerisms are real or a bit of an ironic put-on that became Olbermann’s default setting after a time.

“Keith, how you been?” Hannity asks with a grin.

The congeniality is a bit startling. Olbermann is the ornery host of MSNBC’s Countdown and a newly minted, if unintentional, hero of the left. Five nights a week, he gives the president a beat-down so severe that it almost makes you feel sorry for the man (almost). Hannity, meanwhile, is a Fox News icon with a major Rudy Giuliani crush.

Nevertheless, the two men chitchat pleasantly until Hannity realizes a reporter is present and freaks. “This is off the record,” says Hannity, perhaps fearing a red-state backlash. “Well, you can say I think Keith is a great guy.”

Olbermann displays no such penchant for diplomacy. After the two say good-bye, he heads downstairs to a waiting Town Car that will take him to MSNBC’s Secaucus, New Jersey, studios. “I haven’t figured out who will be my ‘Worst Person in the World’ for today,” he says.

“Worst Person in the World” is a nightly feature of Countdown. Some days, the Worst Person is a Rummy- or Gonzales-quality viper. Some days, it’s a hapless soul whose lone mistake is trying to make a living in Olbermann’s chosen profession. Olbermann’s arch-nemesis, Bill O’Reilly, has earned the distinction scores of times. Hannity, a multiple Worst Person himself, is barely out of earshot when Olbermann finishes the thought. “I’m sure there won’t be a shortage of candidates.”

Keith Olbermann is pissed off. That’s nothing new. Keith Olbermann has been pissed off since he could lift the toilet seat. What’s new is that the 48-year-old Olbermann has lately taken to directing his considerable, bred-in-the-bone rage at high-value targets. That’s a fresh wrinkle. Yes, at ESPN, Olbermann was hugely popular—a pioneer in the now-stultifying genre of the loudmouthed, blow-dried smart-ass sports anchor. But in the end, this was sports. How much did it matter, really, that Bobby Knight tossed another chair? After ESPN, Olbermann took a job hosting a nightly hour-long talk show called The Big Show for the then-fledgling MSNBC (he also occasionally hosted sports programming and sporadically anchored the weekend news for NBC). On that program, Olbermann offered wry commentary about Monica Lewinsky and similar fodder, but again, his bombast seemed out of proportion to the issues at hand.

As an employee, Olbermann was his own kind of Worst Person in the World. His sense of superiority and caustic vibe eventually cost him gigs and friends at three networks. How naughty was he? Olbermann was the only former ESPN star not invited back for the sports network’s 25th anniversary (he’s allowed to participate on Patrick’s radio show only because Patrick promised that Olbermann would never set foot on the network’s Bristol, Connecticut, campus). He was fired from his first stint at MSNBC after he denounced his own show in a commencement address at his alma mater. Fox hired him to host its major-league baseball Game of the Week and then sent him home with a year left on his contract simply for being a malcontent.

That was then. Now, in his second go-round at MSNBC, Olbermann is doing politics, and he’s found his sweet spot. In politics, incompetence doesn’t lose pennants; it gets teenagers killed in a faraway land. Suddenly, viewers didn’t see Olbermann hauling off on hapless foes; they saw him speaking truth to power. “I think there was a lot of times where Keith’s anger was directed to targets not worthy of his anger,” says Dan Patrick. “Now he’s going after presidents and secretaries of State. They’re more worthy than Barry Bonds or a network executive.” Viewers also see a lefty who isn’t afraid to mix it up—Keith the Impaler. Ever since Olbermann ripped into Donald Rumsfeld in a much talked-about August 2006 Countdown segment, his popularity has soared. Improbably enough, the former SportsCenter anchor has even been credited with helping to effect the Democratic takeover of Congress this past November. Here, at the outset of the 2008 presidential season, Keith Olbermann may not be as popular or influential as Rush Limbaugh, but Olbermann has his own dittoheads (Olberites?). They just happen to drive Honda Elements with a dedicated iPod port.

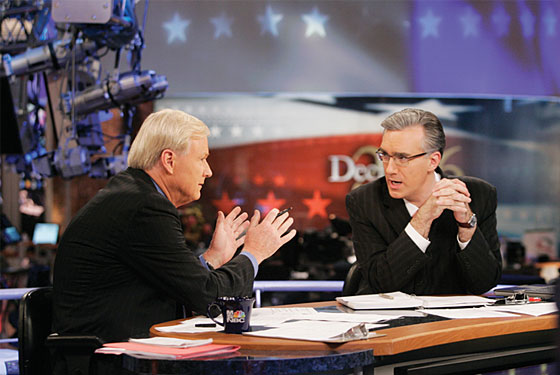

It’s a couple of hours before his nightly broadcast, and Olbermann is looking through boxes of mail in his Secaucus office. “Maybe this one contains Chris Matthews’s eyebrows,” he says, referring to his fellow MSNBC host. “You see them last night? Did he borrow them from Joe Pesci?”

When it’s time for the show to begin, Olbermann sits alone on the Countdown set. Tonight, Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter is in the studio for a conversation, but he’s tucked into an auxiliary room (Olbermann doesn’t share the Countdown stage with anyone). After Alter talks about global warming, there’s a segment on the Scooter Libby trial followed by video of Paul Wolfowitz at a Turkish mosque, taking off his shoes and exposing socks with holes in them. “Wolfowitz seems completely unembarrassed by the ordeal,” says Olbermann. “Then again, after Iraq, how could you be embarrassed by anything?” He segues into a segment on a chicken born with duck feet.

I’m watching from the wings with Jeremy Gaines, an MSNBC flack. “Did you hear that snort he just did?” asks Gaines. “That’s Keith’s imitation of Matthews.” Gaines then bites his lip as if to say “oops.” He tries to respin. “But they really, really like each other.”

Bill O’Reilly has liberal guests on so he can skewer them. Olbermann’s visitors are affable yes-men providing can-I-get-a-witness nods to the latest gem proffered by their all-knowing host. After a commercial, Olbermann interviews Countdown regular John Dean on the Bush administration’s alleged abuse of executive orders. Olbermann eventually does “Worst Person in the World.” Tonight, he gives the silver medal to O’Reilly for supposedly blaming the victim in a child-kidnapping case. Then he gives O’Reilly the gold as well for promising to send a copy of his latest book to an American soldier for every copy bought at full price. “Bill, why do you hate the troops?” mocks Olbermann.

During the final break, Olbermann checks his hair in a Snow White–size mirror and twiddles his BlackBerry. Then he launches into another five-minute pummeling of the president. Tonight, he’s questioning the authenticity of the four terrorist plots that Bush, in his State of the Union speech, said his administration had foiled. “What you gave us a week ago tonight, sir, was not intelligence but rather a walk-through of how speculation and innuendo, guesswork and paranoia, daydreaming and fearmongering combined in your mind and the minds of those in your government into proof of your derring-do and your success against the terrorists, the ones that didn’t have anthrax, the ones who didn’t have plane tickets or passports, the ones who didn’t have any clue, let alone any plots.”

A moment later, Olbermann ends the show with Edward R. Murrow’s “Good night and good luck” (Murrow was an Olbermann boyhood hero). Then Olbermann tosses his script pages into the air, and he’s done for the night.

The whole affair is classic Countdown: moments of juvenile absurdity followed by moments of biting, sincere, and genuinely affecting commentary.

Olbermann has been hosting Countdown since March 2003, the month the U.S. invaded Iraq, and the show has grown progressively anti-Bush as the situation there has deteriorated. But it wasn’t until last August—when Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was implying that those in favor of staying the course in Iraq were Churchillian while those opposed were modern-day Neville Chamberlains—that Countdown began to click.

“I was sitting on the tarmac in L.A.,” recalls Olbermann over lunch at the Meridien Hotel. “I’d exhausted all conversations with James Gandolfini, who was on the flight. And I thought, ‘Where is the outrage? Where are the constitutional- scholar conservatives coming out and going, “This guy is a danger to the democracy. Not to the Democrats or Republicans but to the democracy.” Where is that person?’ ”

Olbermann pauses. “Then I thought, ‘Oh, yeah, I have a newscast, don’t I? I have editorial latitude, don’t I? Well, I guess it’s my turn. Let me strap the jetpack on.’ ”

The next night, Olbermann delivered a six-minute jeremiad against Rumsfeld. It began with the lines, “The man who sees absolutes where all other men see nuances and shades of meaning is either a prophet or a quack. Donald H. Rumsfeld is not a prophet.” Olbermann’s outrage read real, not focus-group manufactured like much of cable punditry. Even a Bush acolyte had to admire Olbermann’s eloquence.

Suddenly, Olbermann was a player in the war debate. Countdown’s ratings spiked, making it MSNBC’s most-watched show. Everyone from the Washington Post to the National Review was talking about Olbermann as a pop liberal antagonist. On the streets of Manhattan, strangers began flashing him thumbs-up. One afternoon a few weeks ago, I was having lunch with Olbermann when no less a left-wing eminence than Ted Danson approached him. “Excuse me, I just wanted to tell you how much I appreciate what you’re doing every night,” Danson offered. “Thank you, and keep it up.”

“People say, ‘You may have been the difference in the election,’ ” says Olbermann. He gives a shudder. I can’t tell whether it’s genuine revulsion or managed humility. “I’m like, ‘Oh, Christ, I don’t want that.’ I’m not out for some power trip on this. I have some personal and professional ambition, but in terms of influence, I just want to see the truth out there.”

Olbermann says he doesn’t vote, and he insists his Bush bashing isn’t ideological. “Look, I didn’t begin this show in 2003 with ‘This is a damn-fool war,’ ” says Olbermann. “We in the media were guilty of assuming our government wouldn’t lie to get us into war. We were largely exploited because we gave them the benefit of the doubt after 9/11. They couldn’t have choreographed it any better if they tried. What angers me is their certainty. The closer you get to something, the less certain you should be of your position. That doesn’t happen with these people. The number of opportunities and chances to redirect this that have been missed is tragic.”

Up until January, everyone who counted was a Republican, says Olbermann. “If the Democrats continue to drag their feet on what the country surely wants, which is non-escalation, I’ll go after them in the same terms: ‘Why are you not listening? Who do you think you answer to?’ ”

It may be true that the roots of Olbermann’s rage aren’t political, strictly speaking. His anti-Bush rants are as much about a kind of reflexive populist anger as anything. But it’s also true that Olbermann doesn’t tend to go after Democrats with the same bloodthirsty zeal with which he attacks the Republicans. In January, when Olbermann asked Hillary Clinton, “Would you apply the word mistake to your vote to authorize the war in Iraq?” she bobbed and weaved and never answered the question. Olbermann didn’t follow up and instead steered the dialogue to safer ground. In October, Olbermann ran a prerecorded segment of an interview he did with Bill Clinton, at the end of the Clinton Global Initiative meetings. One of the ideas discussed at the conference involved creating educational opportunities in Africa. Before he asked his first question, Olbermann handed Bill a check, saying, “Here’s eight more schools in Kenya from me.” While the thought might have been noble, the gesture didn’t exactly smack of political objectivity.

It probably won’t come as much of a surprise that when Keith Olbermann was a kid, he got the tar kicked out of him on a regular basis. And not by the football team. “I got beat up by girls all the time,” says Olbermann. “They literally posted a sign-up sheet and would take turns. I think that’s why I’ve always been such a fan of Mencken’s line, ‘Afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.’ I’ve been afflicted.”

Olbermann’s affliction began at age 5, when his Westchester parents—his father was an architect, his mother a preschool teacher—jumped Olbermann from kindergarten to second grade. “I don’t recommend that,” says Olbermann. “I was always trying to match my intellectual maturity with an equal emotional maturity, and it didn’t work.”

At age 9, Olbermann started collecting baseball cards, even climbing into Dumpsters to collect special 3-D editions thrown out with Twinkie boxes. On television, Olbermann was entranced by former iconoclastic Yankee turned New York sports anchor Jim Bouton. On the radio, he avidly listened to Bob and Ray, the deadpan New York comedy duo who dominated the AM dial in the fifties and sixties. He also memorized late-night reruns of Murrow broadcasts. In junior high, Olbermann spent his summers poring over transcripts of the Army-McCarthy hearings and reading Teddy White’s Making of the President books.

By high school, Olbermann decided he wanted to be a broadcaster. At the Hackley School in Tarrytown, he met an older kid named Chris Berman (the future ESPN fixture), and the two classmates ran a half-watt school radio station. Graduating at 16, Olbermann shipped off to Cornell as the school’s youngest freshman. It wasn’t much fun. His parents went to extreme lengths to make his dorm room the only one in Ithaca with cable TV. Between tearful calls home, Olbermann sat alone and watched the tube. “Thank God for Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” says Olbermann. “Or I might not have made it.”

Olbermann skipped classes to report for his college radio station on the championship Yankees teams of the late seventies. After graduating, he landed sports-anchor jobs in Boston and Los Angeles. Olbermann’s L.A. sportscast sometimes finished seventh behind reruns of Spanish-language soap operas, but people noticed the quirky guy who once ate prime rib during a broadcast.

In 1992, ESPN director of programming John Walsh hired Olbermann and paired him with Dan Patrick to host the 11 p.m. edition of SportsCenter. The smart-ass New Yorker and the Ohio high-school hoops star quickly established a winning, irreverent rapport. There were T-shirt-launching catchphrases, like Patrick’s “En fuego” and Olbermann’s “If you’re scoring at home, or even if you’re alone … ,” and the pair became the model for sports anchors as TV stars. Eventually, Aaron Sorkin would base his sitcom SportsNight on the duo. (Olbermann once claimed that both characters were based on him.)

Still, where some saw a brash breath of fresh air, others saw a self-righteous gasbag. And despite the show’s unprecedented success (Olbermann and Patrick were SportsCenter’s most popular duo), Olbermann was a world-class agitator. He began firing off thousand-word memos to management, lobbying on causes from saner hours for lowly production assistants to profit-sharing for ESPN employees who were helping the network generate billions. Along the way, he won a reputation as a miserable jerk.

“Of all the people I’ve known inside and outside of the business, he was the unhappiest,” recalls a SportsCenter staffer. “Sometimes, at the end of the night, I’d leave early just so I wouldn’t have to give him a ride home. And it wasn’t out of my way.”

In 1997, Walsh allowed Olbermann’s contract to expire, and Olbermann escaped to his NBC and MSNBC gigs. “I’d always wanted to do news,” says Olbermann. “But every time I had a chance to leave sports for news, I’d find a reason not to do it.”

In quintessential Olbermann form, he was ready to quit the show before it started. That Labor Day weekend found him in the Hamptons along with then–Today-show producer Jeff Zucker and Phil Griffin, a longtime Olbermann friend and soon-to-be producer of his MSNBC show. The weekend was going well until news came in that Princess Diana’s limo had crashed inside a Paris tunnel. According to a source familiar with the situation, Zucker and Griffin began dialing their cell phones furiously while Olbermann panicked, alternately chanting, “We’ve got blood on our hands” and “I’m not going to be able to do the show.” (Olbermann denies this characterization.)

Ultimately, Olbermann went ahead with the program. The Big Show was essentially a free-ranging forum for Olbermann’s edgy, quick-witted commentary and polymathic interests. But when the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke, the show morphed into an all-Monica-all-the-time format—a development Olbermann couldn’t stomach. “All the yelling on the show reminded me of a part of my childhood that I didn’t want to relive,” recalls Olbermann. “I just couldn’t deal with it.”

In May 1998, Olbermann gave the commencement address at Cornell. “There are days now when my line of work makes me ashamed, makes me depressed, makes me cry,” Olbermann told the assembled soon-to-be graduates. “About three weeks ago, I awakened from my stupor on this subject and told my employers that I simply could not continue doing this show about the endless investigation and the investigation of the investigation, and the investigation of the investigation of the investigation.” The speech, naturally, didn’t go over well at MSNBC. Olbermann stayed on through that fall, but in December, his contract was sold to Fox.

Olbermann moved to Los Angeles, doing baseball pregame shows and a quirky Sunday-night news show that was critically acclaimed and universally unwatched. But again, Olbermann was unhappy. He bought a house on the Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica, but found it too noisy and moved out after a week and a half. Then he moved into a posh Santa Monica hotel, but eventually left over a billing fight involving $16,000 worth of disputed phone calls. In May 2001, Fox canceled Olbermann’s show and took him off their baseball broadcasts, eight months before his contract was up—with no explanation. In June, Fox bought out the remainder of Olbermann’s deal.

That summer, Olbermann was a man without a broadcast. He moved back to New York, and was working on a novel when he had a dream in which JFK appeared before him on a bus, his head wound dressed with plaster of Paris. In the dream, JFK had just one question for Olbermann: “Why did you leave SportsCenter?” (The novel was never published.) That summer, Olbermann spent hours tending to his baseball-card collection, feuding with the L.A. hotel, and generally nursing grudges against the world. Even longtime friends Patrick and Griffin were at loose ends on how to help their friend.

Then 9/11 happened. “Please don’t say how my life changed on 9/11,” said Olbermann. “I didn’t have some epiphany. It trivializes people who really suffered.”

But something changed. After the towers fell, Olbermann began filing freelance dispatches from Manhattan for an L.A. radio station. They were surprisingly moving and heartfelt. For the first time, Olbermann seemed to have found a purpose.

By 2002, Olbermann was in full rebuild mode, penning a 3,000-word Salon piece, titled “Mea Culpa,” apologizing to ESPN for his years of churlish behavior. Olbermann wrote, “I have lived much of my life assuming much of the responsibility around me and developing a dread of being blamed for things going wrong. Moreover, deep down inside I’ve always believed that everybody around me was qualified and competent, and I wasn’t, and that some day I’d be found out.”

Where did his feelings of inadequacy come from? “My frustration has been over many years of never being able to be an irresponsible kid,” says Olbermann. “I’ve always felt like I was the designated driver 24 hours a day.”

In late 2002, Phil Griffin brought Olbermann back to MSNBC as a guest host on the Jerry Nachman program. With the network foundering in a distant third place to CNN and Fox News, Griffin gambled and gave Olbermann a second chance.

Olbermann has had his bumps in his current gig. It took time for Countdown to find its audience, and Olbermann, despite having significantly mellowed by most accounts, has again had run-ins with colleagues. In December, when Dan Abrams, a former MSNBC talking head and now the network’s general manager, offered praise for Olbermann’s show, Olbermann repaid him for the favor by saying, “I don’t know what Dan has to do with [my show], frankly. We’ve never had a conversation about the direction of the show.” And he once told a viewer via e-mail that MSNBC reporter Rita Cosby is “nice, but dumber than a suitcase of rocks.”

Still, four years in at MSNBC, Olbermann is probably about as happy as he can be. With his newfound success came a fresh contract, reportedly worth $4 million a year, and the promise of prime-time Countdown specials. Once a recurring “Page Six” figure for his dating escapades, Olbermann recently moved in with his girlfriend, Katy Tur. Yes, she’s a 23-year-old 2005 graduate of the University of California, Santa Barbara, but the relationship marks his first attempt at cohabitation. For the moment, anyway, Olbermann seems to have achieved a measure of peace. “It takes some people a long time to find their happiness,” says Olbermann’s friend and producer, Griffin. “Keith has that now.”

At the end of The Candidate, Robert Redford turns toward a crony at his victory party and says, “What do we do now?” Post-2006, Keith Olbermann is facing the same problem. With Bush headed toward irrelevance, Olbermann’s favorite target is passing from the scene. What’s a W. basher to do?

Olbermann insists he’ll slam whoever deserves slamming, and that that strategy will serve him fine. Unlike his sworn enemy, O’Reilly, who proclaims almost nightly how he will use his program to hold presidential candidates accountable, Olbermann is reluctant to say how Countdown will cover the 2008 election. “I hesitate to plan stuff,” says Olbermann. “Then you get away from it being organic.”

Not that Olbermann lacks opinions on the candidates. A few weeks ago, on another ride out to Secaucus, I toss out names like clay pigeons for him to blast down.

Giuliani: “He had a great finish, but the rest of the time he was a schmuck.”

Hillary: “When I interviewed her, she didn’t seem preprogrammed. It was like she had gone to Hillary boot camp: ‘Don’t answer like that. Smack! Answer like this.’ If she doesn’t Alex Rodriguez everything, she may get through.”

Obama: “At the end of our interview last October, he asked me who I thought was going to win the World Series, the Cardinals or the Tigers. I told him the Tigers. And he said, ‘Yeah, I think they’re going to beat them fairly easily.’ At that point, I realized, ‘He’s from Illinois, and downstate Illinois is Cards territory.’ He was willing to pick against the Cardinals on national TV. He’s willing to say, ‘You’re not going to agree with everything I say.’ The politician who can do that is the one who is going to cut through. I don’t think that’s going to be Giuliani. I don’t think it’s Mitt Romney or McCain.”

Earlier, for the sheer sport of it, I had asked him about O’Reilly: “It wasn’t until I left MSNBC in December of ’98 that Bill took second place. Seeing what he did with that and the perversions of television he’s created, I felt bad about it. I might have been able to stop this. It must be like the way Gore or Kerry wake up in the middle of the night thinking, I could have stopped this. I carry that around with me.”

By now we’re at the studio, in a makeup room, and Olbermann starts in on Anderson Cooper. The CNN anchor, Olbermann notes, recently told a Men’s Journal writer that he wouldn’t talk about his private life. “Don’t tell me you don’t want to talk about personal life when you wrote a book about your father’s death and your brother’s death,” says Olbermann. “You can’t move this big mass of personal stuff out for public display, then people ask questions and you say, ‘Oh, no, I didn’t say there was going to be any questions.’ It’s the same thing as the Bush administration saying, ‘We’re going to war, but you really aren’t allowed to know why.’ ”

Olbermann checked his hair in the mirror just as a worried PR assistant materialized. But he wasn’t done. “Don’t tell me you can’t talk about your personal life and then, when they send you overseas and you do a report that consists of your voice-over and pictures of you in a custom-made, blue-to-match-your-eyes bulletproof vest, looking somberly at these scenes of human devastation—like a tourist—and that’s your report. Your shtick is your personal life.”

It was a vintage Olbermann screed, almost lyrical in its vicious eloquence. But at the same time, it felt off again—too big a gun for too small a target.

For a moment, it made me think that Olbermann will, in fact, be lost without Bush.

But not so fast. I asked him what would happen if peace were to break out in Iraq and, more improbable still, if O’Reilly were to follow Bush into a glorious retirement.

“If there’s nothing to complain about, I’m not going to fictionalize anger,” Olbermann said. “Then I become everything I despise.”

He grinned a gloomy grin as he contemplated a universe without Worst Persons in the World. Then he brightened. “But I think that is highly unlikely.”