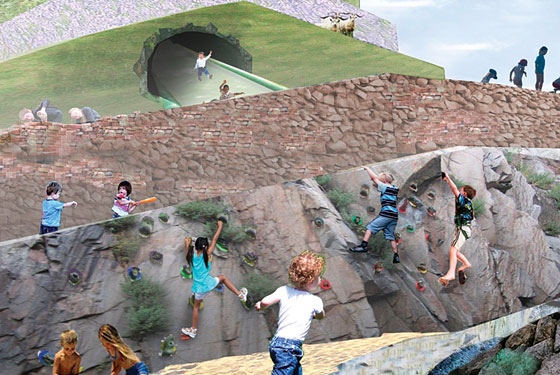

Rendering: REX/MDP/Image by Luxigon

Tooling around the outer edge of Governors Island on a glorious spring day, it hardly seems like it would be difficult to motivate people to go out there. What you see looking out is the movie version of New York City, the coming-to-America view of the Statue of Liberty, the glittery skyscrapers along the Battery. What you see looking in is Nolan Park, a charming row of yellow clapboard houses, flowering trees that shiver pink petals over the lawns; Fort Jay, its bermed sides covered in grass—and, on the South Island, an 80-acre wasteland of Coast Guard structures, slowly falling to pieces.

In other words, Governors Island, sitting at the mouth of the East River, a half-mile below Manhattan, is a jewel—but it’s also a remarkably difficult development conundrum, whose recent history is littered with failed plans. First of all, how is anybody going to get there? The aerial gondola designed by Santiago Calatrava was a beautiful idea, but one that seemed to be a fantasy. (In fact, it’s currently undergoing feasibility studies, and may yet happen.)

The bigger question, of course, is why anyone would want to go. The federal government sold Governors Island to the city and state for $1 (the city and state administer 150 acres; the National Park Service is responsible for 22 more) with a number of stipulations, the most restrictive being no residential development. Back in the day, the city was looking for one big idea for the island. (The Giuliani administration floated the idea of a casino and five-star hotel but was thankfully thwarted.)

A request for expressions of interest in 2005 brought out a grab bag of parties, from the Related Companies and the Durst Organization to the New Globe Theater (still vying for a place at Castle William) to a Tivoli Gardens–esque children’s park complete with giant London Eye–inspired Ferris wheel. Nickelodeon proposed the obvious theme park; Durst was in on an idea for a sustainable cuny campus. Both Industria Superstudio and IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center were interested, as was Friends Seminary. The city hired Toronto-based planners Urban Strategies Inc. to analyze the responses, coagulating them into four themes: Iconic Island, stocked with functional and sculptural works of art and architecture; Innovation Island, an incubator for new research, education, and business ideas; Destination Island, the theme-park option; and Minimum Build Island.

Last year, the city solicited more-specific ideas from the private sector for master plans, but the request didn’t bear fruit. Developers (not exactly a shock) did not want to pony up for new docks, new roads, or new parks. They were waiting for the city and state to make Governors Island a destination island.

As City Hall’s maker of big plans, Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff gets fingered for the failed request for proposals, but he says he was always skeptical. “We could have gotten a person that wanted to create a legacy and do something truly spectacular. In this era of fabulous wealth, it was worth a try,” he says. And Doctoroff still thinks that a global health institute—or an environmental one—could work.

So the city went back to the drawing board—or, actually, five of them. Five design teams were asked to conceive a new landscape, from 25 to 40 acres, for the southern end of the island, and a new 2.2-mile promenade encircling it, and to rethink the open space in the northern historic section.

The essential question all five teams need to answer is, Why have this park? “Everyone knows how to get to Prospect Park or Central Park,” says Leslie Koch, president of the Governors Island Preservation & Education Corporation. “What is the experience that this park and promenade can provide that is unique? This has to be compelling.” Compelling enough to make us get on a ferry or water taxi, and go to New York’s own Nantucket. The visions on the following pages are a first step toward compelling.

And the question is even being posed to the public: Would you go there? After May 31, the five plans will be exhibited both on Governors Island and at the Center for Architecture on La Guardia Place, with comments requested. The island itself will be open to the public on the weekend all summer, with a free, seven-minute ferry from the Battery Maritime Building. A jury will recommend a winner by fall—at which point the next and more difficult phase will begin.

First, all sorts of other dreamers want to impose their vision on the island. Landscape architect Stephen Whitehouse, who developed a concept for Governors Island in 2003, thinks a spa is a no-brainer. Art dealer Daniel Wolf proposed a children’s island including playgrounds by wife Maya Lin, a Takashi Murakami fountain, and new Gates by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Julie Menin, chair of Community Board 1, wants playing fields. Joseph Melillo, executive producer at bam, thinks the island needs its own creative director to seek site-specific events.

But the bigger problem is finding developers with real money. Mark Strauss, a partner at architecture and planning giant FXFowle, thinks that the park alone will not be enough of a draw. “I don’t see the park as a catalyst in itself for attracting people and investment,” he says. “There has to be a vision from the top, and I think it could be academia. Columbia moved up to 116th Street 100 years ago because they were better off selling their existing land and being pioneers.” Downtown’s current gorilla, crushing all townhouses in its path, is NYU. Could it leap the East River?

But, at long last, something will happen at Governors Island. Demolition of the Coast Guard facilities could begin within a year. It shouldn’t be a fantasy much longer.

Rendering: REX/MDP/Image by Luxigon

THE GRID

The basis of this plan, by architect REX and landscape architect Michel Desvigne, is the grid. But what they propose is hardly Manhattan’s gridiron. Rather, it is Jefferson’s, dividing the entire island into 55-by-55-foot units that would then be planted, paved, planked, and filled with grass, hard court, cedar, water, or sand to create a thick perimeter of people-intensive programming: beach, sports facilities, boating, stages, and amphitheater seating to watch the informal parade. “We didn’t want it to be just a treadmill for views,” says REX principal Joshua Prince-Ramus.

The interior would be low-cost, low-impact micro-agriculture, woodlands, water meadows, pastures. Places to dig a hole, to participate, not just watch. “It is not fake nature designed to look picturesque,” says Prince-Ramus. “We want it to be what it is: synthetic.”

Prince-Ramus wants to make sure that the park his team designs works on its own terms, and as a core around which development can happen. He points out that a 14,000-person amphitheater requested by the city would take six hours to fill with the current ferry service. And he thinks half the project’s $200 million budget will go just to infrastructural issues like preventing erosion. That said, he is optimistic. Their grid would allow whatever happens—conference center, museum, campus—to be plugged in without disrupting the pastoral center. While silvery cubes glimmer in the background of several renderings, the plan offers no architecture per se: “No one has the right to design a boathouse yet,” Prince-Ramus says. “Credibility before beauty.”

Rendering: Hargreaves Associates/Michael Maltzan Architecture

THE NECKLACE

Hargreaves Associates and Michael Maltzan Architecture take a necklace as its dominant metaphor. “We thought of the promenade as a necklace with several strands,” says George Hargreaves, “and then these jewels on it that are plazas or activities.” The jewels are buildings, which echo the fluid lines of the public spaces and places, with few right angles. There is a double-ring hotel and conference center, an ecology center set over new wetlands to the west, and another doughnut creating a pool in the southeast. Flowerlike canopies shade multiple ferry terminals, and there is a rippling cover (Maltzan is a former Gehry employee) over the amphitheater—an open, grassy space that flows into a lawn and playing fields. The promenade loops like a racetrack in and out from the land to various piers. Many walkways would be fitted with solar canopies that would, with the power generated by windmills set in a new range of pine barrens, take the southern end off the grid.

Hargreaves picked Maltzan to design the architecture because of its winning plan for the Los Angeles State Historic Park, and because of Maltzan’s experience designing MoMA QNS. “I realized he has faced this problem before, of creating something ‘out there’ and getting people to go out there,” Hargreaves says.

Rendering: Hargreaves Associates/Michael Maltzan Architecture

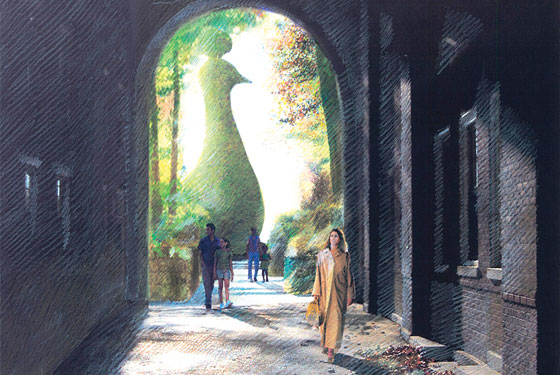

Rendering: West 8/Rogers Marvel Architects/Diller Scofidio + Renfro/Quennell Rothschild/SMWM

THE PATH

A large team (composed of landscape architects West 8 and Quennell Rothschild & Partners, architects Rogers Marvel and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and planners SMWM) proposes a hybrid of landscape and architecture, based around a sinuous set of new watercourses and paths. Development would follow the eastern edge and hug a new waterway, with a DS+R ferry terminal. Proceeding south, a visitor would encounter the Vertical Landscape, mountains popping up out of the flat southern tip that would integrate active recreational, cultural, and educational functions. Inside could be snack bars, exhibits, a funicular, and caves for spelunking. Says West 8 partner Jerry van Eyck: “We wanted to give it the attitude of a national park, one with primal nature, robustness, where you don’t feel the hand of man.” (Although with certain amenities: The plan would also supply 3,000 wooden bicycles and 3,000 wooden armchairs.)

Rendering: West 8/Rogers Marvel Architects/Diller Scofidio + Renfro/Quennell Rothschild/SMWM

Rendering: Field Operations

THE SHELL

Called “Mollusk,” the plan developed by Field Operations and WilkinsonEyre is encapsulated by an ideogram of a ridged, bumpy shell encircled by a golden path. “It should be a fairly empty landscape,” partner James Corner says. “No clutter. We want to maintain the scale of being out there in the harbor and the sense of vulnerability, of exposure.” The golden path represents the required promenade, which would create a hard edge all the way around the island. Within that band, the flat southern topography would be sculpted into a series of soft hills, crowned by flowering meadows. In a certain sense, FO’s is the most Olmstedian proposal, as it creates a naturalistic landscape on landfill from 1900, a place that could immediately seem like it had always been there.

But there are plenty of 21st-century touches. Facing Brooklyn, there would be protected boating areas, a beach carved into the island, and a floating pool set on the edge. At the far end, the land would be carved down, creating tidal pools that could fill with the bay’s original mollusks. Farther north are a set of thermal pools, heated in winter like an Icelandic sauna, and the Nest, a global weather institute. FO is already designing the landscapes for both the High Line and Fresh Kills parks, so it would have to be considered the front-runner.

Rending: Field Operations

Rendering: WRT LLC/Urban Strategies, Inc.

THE NEST

The Philadelphia firm WRT, teamed with Urban Strategies, from Toronto, mixed its inspirational metaphors. “We were looking at forms in nature like oysters and pearls and stem cells,” says WRT partner Margie Ruddick. “Things that have a forgiving architecture, and where one thing is nested in another.”

Her team’s plan carves a series of interlocking ovals into the flat southern landscape, nesting a play lawn inside a larger great meadow, and an artificial hill inside a new wetland at the southern end. Rather than building up the center, the WRT scheme builds up the edge, stringing a series of structures that could house a spa and retreat center on a rocky promontory, plus a working waterfront along the Brooklyn side. These buildings, however, would not pop up out of the landscape but be part of it: Green roofs would slope up from the interior toward the water at one or two stories, turning the center of the island into a protected bowl.

“I have been reading Last Child in the Woods,” Ruddick says. “It is about how those of us who connected very closely to nature as children have a sense of responsibility for it. I thought at one point of calling it Gore Island.” To this end, the team envisions a camp in a new forested ravine and a sustainable farm and garden. The southwest side of the island has evolved into a sandbar beach and reef. The plan has a hotel on the west side (perhaps one of the new Starwood eco-hotels), but not for the business traveler: “It should be considered a retreat.”

Rendering: WRT LLC/Urban Strategies, Inc.

SEE ALSO:

■The Grid

■ The Necklace

■ The Path

■ The Shell

■ The Nest