Near midnight on August 11, Anthony Marshall and his wife, Charlene, approached the front door of Holly Hill, the Westchester estate that belonged to his mother, Brooke Astor, who was dying. As they drew close, Mrs. Astor’s British butler posted himself in the doorway and shot his arms to the sides.”You can’t come in here,” he told Charlene. “I have my instructions.”

The instructions had been issued by Annette de la Renta, Brooke’s dear friend and now Tony’s adversary. The State Supreme Court in Manhattan had awarded her control over Brooke’s final days after Tony’s own son Philip charged that Tony had abused Brooke, denying her the care she needed. The accusations transformed Tony into a tabloid villain, the greedy, mean-spirited son of society’s grande dame. Now he was vilified even by the butler, whom he’d once fired and whom Annette swiftly rehired.

Tony entered Brooke’s country house alone. He made his way to a guest bedroom, where he found Annette sitting with the Reverend Charles Pridemore, his mother’s local priest. Tony, in tie and Marine Corps tie clasp, walked slowly to Annette and stood in front of her. He’s hard of hearing. He wanted to be close.”I know that Charlene has not been permitted to visit my mother in a year,” he told Annette stiffly, “but I would like it if she could come up and see my mother. This may be the last time.”“No,” she said vehemently. “You have to talk with lawyers.”Tony thought this was cruel and unjust and horrible. But there was nothing to be done—he couldn’t disobey the court.

Tony walked to his mother’s bedroom, followed by the Reverend Pridemore. Out one window, he could glimpse the Hudson River and some of the 65 acres of the estate his mother loved to stroll with her dogs. Brooke Astor, who was once, as many a journalist said, the most popular person in New York, lay under a soft pink quilt. She’d been dressed in white, her hands folded, a prayer book placed under her arms. “I had a wonderful life,” she often said, and left instructions to use the phrase on her tombstone. It was also an improbably long life. In her 105 years, she’d become a living monument, giving away $200 million from “my foundation,”as she called it.

Now she had trouble breathing, she could barely swallow; her arms were black from poor circulation. She weighed perhaps 75 pounds. Tony sat on the pink quilt and shuffled the frail woman into his arms. Her makeup was done. The nurses had put it on just as she liked. Red lips, blue eye shadow, pink cheeks.

Someone had removed photos of Tony from the marble-topped table next to her bed. Tony’s mother wouldn’t have stood for that, or any of this, he thought. But she hadn’t been able to communicate in a year. His mother made a sound, a little groan. She knows I’m here, Tony thought.The Reverend Pridemore read from the Book of Common Prayer, prayers for ministration at the time of death.“Amen,” Tony said and cried.

Two days later, Brooke Astor, worth $132 million—plus a charitable trust worth an additional $60 million—and who once had been the beloved doyenne of New York society, passed away. And the fight over her legacy began in earnest.

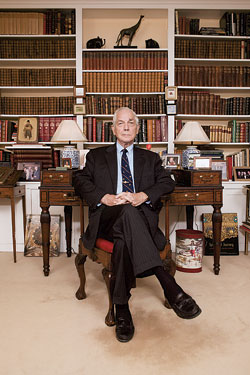

“My mother loved me,” Tony tells me the first time we talk. He’s 83 now, with white hair and watery blue eyes and in the black tie he’s often worn since his mother died. We’re in the living room of his apartment on East 79th Street, an apartment his mother gave him. The room is compact, with chintz furniture, dark coffee tables, no decorator’s touch. Tony has an upper-class accent. (“A-gane,” he says for again.) Charlene sits by Tony’s side; their lawyer and two public-relations people are also in the room.

“Where would you like to start?” Tony asks me. “Trips we took together? How much I saw her in New York? Early years? Mid-years?”

Tony begins with the early years. “She was always there when I needed her,” he says. “Whenever I got sick. When I had a terrible nosebleed, my mother put me next to her in her bed. I stayed right in her bed till the next day.”

He skips ahead. “She loved me in many different ways through the years. She loved me by giving me gifts, whether monetary or an object or Cove End,” her summer estate in Maine. “She also loved me because she included me in trips. One trip was wonderful, starting in Venice, ending in Monte Carlo, where Grace Kelly and her husband came onboard and had a drink.”

Charlene, who is 62 and Tony’s third wife, interjects, distilling Tony’s points. “Brooke had a cluster of personal friends, but her closest companion for 83 years was Tony,” she says. “Not only was he her trusted adviser, but when she felt down, when she had a problem or a concern, it was always Tony she went to.”

Proving a mother’s love may seem a pathetic undertaking—but that’s the situation in which Tony now finds himself. The wills and codicils Brooke signed late in life speed up the process by which Tony comes into his inheritance, and give him more. Upon Tony’s death, Charlene stands to get much more—as much as $50 million—than she was due in wills Brooke signed as late as 2002. And Tony gets more control over Brooke’s charitable giving, and even his own, eponymous foundation. At stake are the millions she’d left in earlier wills to favored charities like the New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which stand to lose some $10 million each. (Of course, they are some of Annette de la Renta’s favorite charities, too.) Annette and others have challenged the wills: It’s obvious to them that if Brooke had been mentally competent, she wouldn’t have favored Tony and Charlene in these ways. Lately, the district attorney has joined the accusers. A grand jury is considering indictments.

To all this, Tony has a simple rebuttal.“My mother loved me,” he tells me. “That’s what I’m trying to get over.”

Of course, being Brooke Astor’s son was never easy. Her boundless energy—her “pep,” as she called it—migrated toward her social life, at the center of which was one husband or another, none of whom had much affection for Tony. Tony’s biological father, John Dryden Kuser, Brooke’s first husband, couldn’t have cared less about his son. Buddie Marshall, Brooke’s next husband, was the love of her life. Tony respected him and took his name, a kind of reverse adoption, in the words of Brooke’s biographer, Frances Kiernan. But Buddie didn’t reciprocate. He felt Tony was spoiled, and selected a boarding school to which Tony was shipped off when he was 11.

After Buddie died in 1952, Vincent Astor entered Brooke’s life. Staggeringly rich and with a gilded New York name, he was also notoriously difficult. “Repulsive,” as Louis Auchincloss, the writer and Brooke’s longtime friend, puts it. “He had bad manners and he showed them all the time.” Astor’s wife, fed up, decided to leave, but first agreed to find a suitable replacement. The leading candidate was the beautiful Janet Rhinelander Stewart, according to Kiernan, whose insightful biography of Brooke appeared this year. Stewart, who had her own money, shot Astor down, even after he assured her that his doctors gave him just three years to live because of emphysema. “But Vincent, what if the doctors are wrong?” Stewart replied.

Brooke was next in line. And the second time they met, Astor proposed to her. Buddie hadn’t left Brooke enough to maintain her way of life. Astor assured Brooke she’d have $1 million for marrying him, $5 million if she stuck it out a year.

A short time later, Brooke asked Tony, then 29, for advice, He knew she wanted him to say yes. “Think about the life you would lead,” he said. Within a year of Buddie’s death, she and Astor married, another bit of sad paternal luck for Tony.“Vincent was very jealous of me and any time I would spend with her,” says Tony. “He didn’t want us to see each other.” And Brooke acceded. “I saw very little of Tony,” she writes succinctly in her memoir. “I concentrated on Vincent.”

“Brooke married Astor for the money,” says Auchincloss, now 90. “She kept her part of the bargain: to make him happy.” Astor’s doctors turned out to be wrong; he lived for six years. But when he died in 1959, he left Brooke $134 million, half of it in the Vincent Astor Foundation (almost $1 billion in today’s dollars).

Through all her marriages, Tony was often left to grow up on his own. By most measures, he did a fair job. At 18, he joined the Marines and earned a Purple Heart leading a platoon at Iwo Jima. He worked at the CIA, helping engineer the U-2 spy program. Later, he invested in the theater; he and Charlene won two Tony Awards, for Long Day’s Journey Into Night and I Am My Own Wife. He published seven books. He served as ambassador to Madagascar, Trinidad and Tobago, the Seychelles, and Kenya.Then, in 1979, his diplomatic career at an end—his initial patron had been Richard Nixon—Tony went to work for his mother, supervising her finances. At age 55, he became Brooke Astor’s son, which followed him like a title.“By the way,” Charlene explains proudly, “Mr. Marshall made all the money for Brooke [to give away].”

“That’s a little bit of an overstatement,” says Tony. Mainly, he points out, he managed her personal money. That he did quite well. On his watch, her assets grew from $19 million to $82 million. For his efforts, Brooke paid Tony a salary, eventually $450,000 a year. It was a significant amount, though not by Astor standards. “Brooke would always say, ‘Do you have enough? Do you have a cook? Do you have a housekeeper? Give yourself a raise, a bonus,’ ” says Charlene.

“Every time she’d say it, it would embarrass me,” says Tony. “I felt I’m doing this for my mother. Why should I get more money?” Besides, Brooke looked after her “baby,” as she called him even when he was a senior citizen. (“She’d embarrass me,” says Tony. “At age 70, you don’t like that. She meant it nicely, but really without a sense of humor.”) Brooke’s generosity was considerable, though mostly it came late in the game. In 1998, when he was 74, she gave Tony a duplex on 79th Street, near her place at 778 Park Avenue, and later a car and driver. In 2003, when he was 79, she gave him $5 million, his first real payday.

When I mention that it seems as if Brooke preferred to keep Tony dependent, Tony pauses a long time—21 seconds.“If she did want to keep the reins in her hand, she did it unintentionally,” he finally says.Besides, Tony received other compensation—after years away, he was her consort, always close by. He danced behind her, as she later described it. But then who didn’t? “There was no one like Brooke,” says friend after friend. “The most enchanting woman I’ve ever known,” says Auchincloss. At times, both David Rockefeller and his brother Laurance seemed to be in love with her. “She was great fun!” says David, “and she was always, always kissing.” Brooke was a gifted flirt. She quipped that she put herself to sleep by counting her lovers.

To Tony and Charlene, Brooke was trying to make amends by changing her wills. “I think a certain amount of guilt came into her decisions,” says Charlene, “for not being the best mother.”

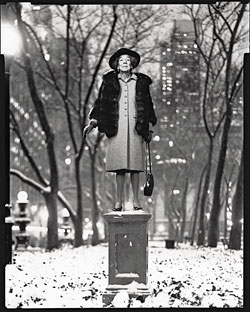

Brooke passed her days giving away money, which she loved. She dressed for the role like the queen mother—it was expected of her, she said, and she wouldn’t disappoint. Then at night, she went out. At 94, she told a friend, “Sometimes I wonder why, at my age, I like to go out every night, but I do.” When she was 100, her doctor recommended less dancing.

Above all, Brooke hated to be bored. And “business,” as a friend explained, “was dull to her.” And so, no doubt, she was relieved to turn the details over to her son, a more practical person. “I don’t believe in wasting money no matter how much you’ve got,” Tony says. “You shouldn’t abuse money.” Tony tried to make Brooke aware of her spending—“Don’t buy a plane,” he joked. Her income was perhaps $5 million a year at the end, a royal sum, unless you’re maintaining three large properties and buying elegant clothes at a rapid clip. Brooke fretted; she always had. For at least fifteen years, she privately quizzed her staff: Do I have enough?

Tony’s job was to worry about expenditures. “One designer double billed my mother for a dress,” says Tony. “A very expensive dress, $25,000. I wrote to him and brought this to his attention.”Had Tony involved his mother, he knows what she would’ve said: “Oh, I want him to like me. I don’t particularly care for him. But I want him to be friendly. Don’t bother with the bill.”“It wasn’t right,” says Tony. “It was only after about five letters and more than six months that I was able to get him to repay.” Tony feels he was simply being responsible; someone had to be. “I became the dirty dog,” he says.As his mother aged, Tony says, his job turned more difficult. Brooke was increasingly “erratic” and impulsive. She fired her social secretaries one after the other—one because her skirts were too short. She spoke about friends “sponging off” her, which, as one confidant said, “was so unlike Brooke.”

When she was 98, Tony wrote to Dr. Howard Fillit, a geriatric specialist, to better understand the changes in her. She was delusional at times, he wrote. “Are you my only child?” she asked him. She misplaced eyeglasses, gloves, and blamed a maid for hiding them. And in lucid moments, she felt awful. “I don’t know what’s the matter with me. I feel I’m losing my mind,” Tony reports her saying.

Dr. Fillit diagnosed mild dementia/Alzheimer’s type, which comforted Tony when she turned on him. One day, she told Tony she didn’t want him to accompany her to the doctor. “You only want to see how soon I will die,” she told him.

As she aged, she increasingly turned to Tony to manage the households. And Tony to Charlene—“We’re married, you know,” he says. “Brooke was very thankful that he was there for her,” says Auchincloss. By 2006, when Brooke was 104, her life was increasingly limited. She’d outlived a generation of friends. Younger ones drifted away; Brooke didn’t always recognize them. Tony and Charlene warned some off.

By then, Brooke used just a few rooms in the vast Park Avenue duplex. Tony felt sensible economies were in order. Brooke’s chauffeur had been with her forever, but now his principal duty was to walk her dogs. Tony and Charlene let him go, saying she could use their driver. In early 2005, Tony and Charlene closed the Holly Hill house and fired the butler.

Brooke’s friends hated that they closed Holly Hill, where they were sure Brooke would prefer to be. One day in spring 2005, Robert Silvers, editor of the New York Review of Books, visited Brooke with Annette. “It isn’t right,” Brooke told them. “I want to go to the house.” She was crying. Tony and Charlene felt it important that she remain in the city, near doctors and friends.

Philip Marshall, one of Tony’s twin sons, was the first to become alarmed about Brooke’s living conditions. Philip, a tenured professor of historic preservation at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island, isn’t close with Tony. His father had left Philip’s mother when Philip was 8. Since then, father and son had spent some pleasant vacations together. Still, for Philip, the word fatherly in relation to his father provokes a laugh.

Philip insists he has no animus toward his father. “My concern was for my grandmother’s well-being,” he says. At times, Philip seems to feel sorry for his father, suspecting he’s subject to stronger wills, like that of Charlene. Whatever sympathies Philip felt, on July 24, 2006, he filed an aggressive petition with the court. He wanted his father stripped of responsibility for his grandmother, and he painted a Grey Gardens–like picture of her living conditions. “My father,” Philip’s petition says, “has turned a blind eye to [my grandmother], intentionally and repeatedly ignoring her health, safety, personal and household needs, while enriching himself with millions of [Brooke’s] dollars.” Philip evinced special concern for his grandmother’s well-being, and her dignity. “Why should my grandmother who was accustomed to dining with world leaders and frequented 21 and the Knickerbocker Club, be forced to eat oatmeal and pureed carrots, pureed peas and pureed liver every day, Monday through Friday, months on end?” “Her Park Avenue duplex is in such a dirty and dilapidated state.” … “Her bedroom is so cold in the winter that my grandmother is forced to sleep in the TV room … on a filthy couch that smells, probably from dog urine.” Nor was she permitted a visit by her beloved dachshunds, Boysie and Girlsie.

Most disturbing, according to Philip, doctors’ visits had been cut back. “Needed prescriptions are inexplicably stopped,” says the petition. Tony refused to let nurses call 911 without permission. Tony, the petition seemed to imply, was trying to hasten Brooke’s death.

Philip approached David Rockefeller, Brooke’s longtime friend, and afterward Annette (Rockefeller also helped pay Philip’s legal bills). Philip proposed that Annette take care of his grandmother. A judge swiftly appointed her temporary guardian, a decision that became permanent as part of a settlement with Tony.

That Philip’s charges of elder abuse proved unsubstantiated hardly mattered. The process he initiated led to other troubling allegations. The court had appointed JPMorgan Chase as Brooke’s financial guardian. Chase alleged that over the past several years, millions had indeed shifted from Brooke’s account to Tony and Charlene’s, and at a time when Brooke was “incapacitated.” Susan Robbins, the attorney appointed by the court to advocate for Brooke, fueled the suspicions, noting that Tony and Charlene received more in the wills as Brooke declined.

In Tony and Charlene’s living room, the sound of a passing siren grows so loud it seems to be in the room. Conversation halts. Charlene serves Perrier. She grew up in modest circumstances and still likes to bake. She sets a plate of chocolate-chip cookies atop a pile of books on a table. “People ask us if we’re going to move to 778 Park Avenue,” says Charlene, referring to Brooke’s address. “No! This is our home.”

The siren fades. Tony returns to an earlier theme, his mother’s love. He has dug up some letters that reveal her feelings. Most date from 30 years ago, when Tony was an ambassador. Tony is interested in sharing them, particularly since he believes they show his mother’s true attitude toward Philip and his brother. “She thought they were only interested in her money,” Tony tells me with raised eyebrows. Charlene has the butler fetch the letters.

The letters are fascinating, though not only for the reason Tony proposes. Brooke is a natural writer, and they are lively, gossipy, snide, among the charms for which she was beloved—Tony’s given me eleven, some of which are excerpts. She names a person who died. “I can not pretend to be sad as I never liked him,” she writes. She confides that she’s going for “a tuck in my face. I definitely need it as I … look a million yrs. old.” She includes telegraphic accounts of her social life. Tony may be the diplomat, but one never forgets that Brooke moves in the highest circles. She dines with Henry Kissinger and a senator and a governor who is “a bit of a bore.”

Tony is right. The letters are loving, adoring, even maternal. “That a man can be happy, completely fulfilled! … My joy is your joy,” she wrote. “You are useful, wise and happy, an unbeatable combination.” Tony’s also right that Brooke rattles off complaints about her grandsons. “They have not been taught anything,” she writes. A graver offense is that they are dull. “If they played tennis or golf or were keen about swimming—if they were gay and anxious to have fun—but they are not,” she writes. Worse yet, they are indifferent to her charms. “One feels it if someone really cares—I have no ‘charisma’ for them.” All her life, Brooke had, as she said, been obsessed with pleasing people. Her grandsons’ indifference hurts. “You know how upset I get if rebuffed. I have never been able to overcome my vulnerability.” Once wounded, Brooke suspects motives. “All I mean to them is money,” she says. “They were very happy when we first arrived in Paris because I was buying them things, but now that the ‘giving’ has dried up so has their affection.”

And yet Tony may have missed the real import of these letters. Brooke complains about the ragamuffin boys (who in these letters are in their teens and twenties), but she is interested in them. She invests in their futures, for which she has hopes. She’s desperate to “open their eyes even a little bit on a world of … good manners and civilized conversation.” And Brooke wants Tony to join in this project. Yes, she runs down Philip’s young male flaws and showers Tony with praise, but Brooke was always an instinctive diplomat. The subtext is that she wants Tony to be the father Philip needs—the one Tony never had. She lobbies for a summerlong father-son reunion in Tony’s latest African posting. “Philip needs help,” she writes. “He needs to respect and look up to someone. No preaching can do it, but to see you in action would be an eye opener for him. I hope that you can arrange it.” She offers to pay his way. “After all,” she wrote, “what is more important than to have your children turn out well?”

No one ever heard Annette de la Renta say she disliked Tony and Charlene. “She has good manners,” says a friend. But Annette and Tony were natural rivals—Brooke liked to say Annette was like a daughter to her. “I knew that Annette loved my grandmother unconditionally,” says Philip.

Brooke and Annette were different. Brooke was regal, the natural center of attention. Annette, who is married to the fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, is shier. Public speaking petrifies her (which made her public effort on Brooke’s behalf “courageous” and “heroic” to her circle). Together, though, they seemed cozy, gossipy. (Annette sometimes flew from her place in the Dominican Republic to Brooke’s Maine house just for lunch.) They loved dogs. After Brooke bought a dachshund named Boysie, Annette, saying the dog was lonely, got her another named Girlsie. They loved clothes; they had great legs. Later, when Brooke was housebound, Annette would stop by on her way out for the evening to show Brooke what she was wearing.

Their friendship continued at the De la Rentas’ coral-stone mansion in the Dominican Republic, Oscar’s native country. Annette said it was a place for family and friends. That included the Kissingers, who jetted down for an en famille Christmas, as well as the Clintons, Baryshnikov, and Barbara Walters. Brooke flew down, too, of course. Once she was there with Betsy Gotbaum—Betsy, New York City’s public advocate, is one of Annette’s childhood friends. Betsy remembers that they swam with the dolphins. Betsy was afraid. Brooke, in her nineties, jumped right in.

Both Brooke and Annette also shared a belief that the upper crust had obligations, particularly to the Culture, capital C. For years, they’d been in a book group together with other dignified socialites, Susan Burden and Anne Bass, and, for intellectual heft, the writer Renata Adler. And together they supported the city’s crown jewels, as Brooke called them. Annette had followed her mother, Jane Engelhard, onto the board of the Met, where Brooke, of course, served, too. (As did Tony, though his participation was, as Annette’s circle says, a favor to his mother.) Annette and Brooke also served on the New York Public Library’s board. The Astors helped found it, and Brooke almost single-handedly made it a fashionable charity, donating $25 million in her lifetime. “It is impossible to overstate her importance,” says president Paul LeClerc. Annette was sure that Brooke wouldn’t forsake the institutions they’d worked so hard for all those years. “Annette felt that Brooke was wronged,” says Betsy Gotbaum. “There’s nothing in this for Annette.”

Tony and Charlene saw things in equally stark terms. “Annette was pushy and wanted to ingratiate herself with Brooke,” says Charlene. She had an eye on Brooke’s social throne. “Brooke was a rung on the ladder for Annette,” says Charlene.

Brooke’s circle, including Annette, were never particularly interested in Tony and Charlene. “It’s not Tony’s fault that he’s kind of boring,” says one. They didn’t credit his accomplishments.

“Madagascar?” a friend had ribbed Brooke. “Have you ever heard of a bad ambassador to Madagascar?” “That’s enough out of you,” Brooke said. And then came the inevitable refrain. “She bought the ambassadorships, didn’t she? Why would anybody make Tony an ambassador otherwise?”

Brooke loved Tony, they conceded. And they knew, too, that Tony had a happy married life. “He has a real marriage, unlike everyone else in that circle,” says one of his friends. Tony sometimes thinks he and Charlene might have been married in a former life. They hold hands, engage in long embraces. Still, says a friend, “no one is going to a party at Tony and Charlene’s.”

Indeed, their relationship, for this crowd, seemed tawdry. Tony and Charlene had met in Maine, in Northeast Harbor, where Brooke summered. For 23 years, Charlene was married to the local Episcopal priest, Brooke’s priest. “He was a good priest, but not a good husband,” says Charlene. “We’d grown apart.” Charlene left her husband in 1989, moving out of the rectory.

“We weren’t naughty,” says Tony.“Not that I didn’t think about it,” says Charlene. “I thought, Wow! What a gorgeous man.”Six months later, Charlene moved to New York. Tony soon decided that his 30-year marriage to his former secretary had run its course. “When I got to know Charlene,” he says, “I decided not to live on in misery but to marry in happiness.”

“I know that Charlene has not been permitted to visit my mother in a year,” Tony said to Annette. “But I would like it if she could come up and see my mother. This may be the last time.”

Ugly gossip followed them. What did the young minister’s wife see in the 65-year-old son of the town’s richest resident? It didn’t help that Charlene left three kids behind. Abandoned them, said the papers, though her kids didn’t feel that way. “Granted, she wasn’t in the room next door anymore, but she didn’t abandon us. She’s always there for all of us,” says her son Robert, 30. But Brooke was displeased, and complained to friends that she didn’t know how she could still go to church.

Of course, Brooke hadn’t cared for any of Tony’s wives. In front of Charlene, Brooke suggested that Tony marry Pamela Harriman, the Washington socialite and widow of Averell. (“I sort of swallowed hard,” says Charlene.) Charlene’s emotiveness, her weight, her laugh—a cackle, one thought—marked her as not one of the club. “Brooke rolled her eyes,” the friend said.

To Tony and Charlene, this was just snobbery. She ministered to the needy, she worked for charity, too. “I think they hate her because she doesn’t fit into their clothes,” says one of their supporters. Some of Brooke’s friends are sure that Brooke hated Charlene. “That wasn’t my experience of Brooke. I thought we were close,” Charlene says. “If I bought a pink sweater, I’d buy her a pink sweater, too. I was going to say we exchanged gifts, but she gave me more than I gave her. We did a lot of things together. We shopped.” Brooke picked out Charlene’s clothes when they shopped. Brooke also lent Charlene pieces of her remarkable jewelry collection. Charlene wore Brooke’s spectacular emerald necklace, Vincent Astor’s last gift, to the Tony awards. She took it as a token of Brooke’s affection; Brooke’s friends saw it as bad form—Brooke wasn’t dead yet.

Whatever her true feelings, Brooke realized that Tony loved Charlene and Charlene Tony. And Brooke, as everyone said, loved Tony. “She makes Tony very happy,” Brooke often said. Tony took this as a great comfort; Brooke’s friends, of course, heard it as tight-lipped dismissal.

Even Tony knows that the fight over his mother’s legacy is in ways a fight about Charlene, the interloper. “There are a number of people actively interested in the case, beginning with my son Philip, who were hoping that this would separate us if not kill us. Instead, we love each other even more.”

Brooke enjoyed making changes to her will in the library at Park Avenue, one of the most beautiful rooms in New York, it’s often said. The bookshelves are detailed in brass, the walls lacquered in red. She had 3,000 leather-bound volumes—“I’ve written some of them,” she said. She’d hung her lovely Childe Hassam painting over the mantel of French marble, not far from an inconveniently located call button—once, one of her many suitors accidentally leaned on the bell in mid–marriage proposal.

On December 18, 2003, Brooke signed a codicil that reads, “After much thought and discussion with my son … I have decided to do for my son, Anthony Marshall, what my late husband did for me. ” She reduced her gifts to the Met and the library and created the Anthony Marshall Fund with 49 percent of her charitable monies. It represented a combined loss for the institutions of perhaps $20 million.

Once before, Tony had been on the brink of such a role. “My mother had said at one point she wanted me to be president [of the Vincent Astor Foundation],” Tony says. Tony was delighted by her change of heart. “I’d love that,” he told his mother. “I think it’d be great fun.” But then Brooke had shut down the charity and spent its assets.

Tony tried out the phrase “my foundation.” He’s considering giving to the American Museum of Natural History.

The losing institutions were furious. “Promises were made” was the word at the library’s trustee meetings. They’d known Brooke’s intentions for years. In anger, the library didn’t invite Tony to his mother’s tribute; nor did the Met.

To Tony, it seemed his growing list of enemies wanted to get at him however they could. In fact, a court evaluator found after extensive investigation that he hadn’t abused his mother, hadn’t reduced her medication or her doctor’s visits; nor did he restrict 911 calls. Her doctor ordered those. Tony didn’t restrict her diet; the court examined the grocery bills. Brooke’s beloved dogs were kept from her, but only because they cut her increasingly fragile skin.

And yet, it’s true that on Tony’s watch her way of life frayed. There was a draft under her bedroom windows; an awning was tattered on the terrace, so she couldn’t take the sun. She had always loved fresh flowers—she’d filled her apartment with them. Tony decreed that flowers were only to be in the rooms she used—and purchased at the local market. Beloved staff members were gone. And the remaining staff feuded. After Tony and Charlene fired the chauffeur, no one stepped forward to walk the dogs. Brooke’s pantry became a dog run. Tony perhaps didn’t even know.

For Philip and Annette, it was so sad. No one was managing Brooke’s care, her life, for her benefit, they thought. It looked all the more scandalous to them because, while effecting practical economies in Brooke’s life, Tony had a new yacht (for which his mother paid the taxes). He embarked on a leisurely summer at Cove End. Holly Hill was shuttered. Tony and Charlene were busy leading Brooke’s life, and with Brooke’s money, while, the charge went, her Park Avenue staff bickered over who would clean the couch.

Why the thrift? “It was Brooke’s money!” said one of Annette’s friends.

Chase’s investigators, starting with that premise, tracked the money. “There were a bunch of transactions during a three-year or so period implemented by Mr. Marshall for Mr. Marshall’s benefit which, we believe, [were] never knowingly consented to by Mrs. Astor and never authorized by her,” Leslie Fagen, the Paul, Weiss attorney representing Chase, told the court. (“Bogus and cruel,” retorts Ken Warner, Tony’s attorney.) Tony, who’d long held Brooke’s power of attorney, signed her checks.

In 2002, Tony says, he stumbled onto a buyer for the Childe Hassam painting. Brooke told a friend she felt pressured to sell it to support her lifestyle. But Tony says Brooke jumped at the chance. “How much did he offer?” she asked. For Chase, the suspicious act is not the sale for $10 million, but the commission. Tony took $2 million. “She wanted me to have it,” says Tony.

The next year, in August 2003, she gave Tony $5 million; “I do want you to have enough money to provide for Charlene on your death,” says a letter she signed on August 12. (“It didn’t come out of the blue,” says Charlene. “Her wanting to help me was a constant conversation for the eighteen years that I’ve known Tony.”) The same year, she deeded him her beautiful Maine property. Tony was always to get it in the wills, but only if he survived his mother. Tony quickly deeded it to Charlene. (Estate planning, thought Tony. He didn’t want his children to have it.)

In 2005, he gave himself a bonus, $2.4 million over two years. For someone with oversight of $82 million, this may not be excessive. He says Brooke’s accountant calculated the bonus. But Brooke didn’t know. “If mother was interested in financial details, I’m sure she would have agreed,” says Tony. Tony didn’t feel he did anything wrong. People told him he was underpaid. “In retrospect, I shouldn’t have done it,” he says. “It doesn’t look good.”

That Brooke’s generosity to Tony and Charlene accelerated in her last years is clear. But it was her wish, he insists. He remembers what his mother confided to him: “I want you to have everything.”Tony wasn’t embarrassed this time. “Thank you,” he said.Perhaps Brooke didn’t announce her intentions widely, but Tony and Charlene understood. “I think a certain amount of guilt came into her decisions,” says Charlene, “for not being the best mother.”“Atoning,” adds Tony.

“Her values changed at the end of her life,” says Charlene. “She wanted to make it up to Tony. She realized more and more of what he did for her. I know it.”

For Tony, his mother’s love had been elusive, but, finally, it came. “It made me sad that she hadn’t felt that way in the past,” he tells me late one evening. “I’m not talking about money, though sometimes money does reflect how one feels.”Chase doesn’t buy any of it. The bank proved a zealous investigator—“overly zealous,” a judge once said. Everything is suspect. The problem is that Brooke didn’t know what she was doing. “Incapacitated,” says Chase’s lawyer.

Tony, of course, had been among the first to notice the dramatic changes in his mother’s mental state. At the end of 2000, he wrote, she got lost on her Holly Hills estate; she washed up on a neighbor’s property, disoriented. “Difficulty in dressing.” “Writing/spelling are increasing problems.” She was confused about whether her income was an annual or a monthly figure. At a board meeting at the Met in April 2002, she couldn’t follow the proceedings. By the middle of 2003, Brooke would often trail off in mid-conversation; her short-term memory was extremely impaired. A staffer prepared a photo album of friends to help Brooke recognize visitors. “It is inconceivable,” says one person who’s examined the medical record, “that Brooke Astor could have understood what she signed.”

No doubt Brooke appeared to have good days. Enough people said so. Perhaps even Annette conceded as much. The day after Brooke amended a 2002 will, Annette accepted a gift from Brooke of a diamond necklace and diamond earclips worth $76,000. In August 2003, when Brooke gave Tony $5 million, her lawyer, Henry Christensen, of Sullivan & Cromwell, attested to her mental competence. He’d known her for years and knew about her diagnosis. “I had a good visit with your mother yesterday at Holly Hill,” he wrote Tony on August 14, 2003. And four months later, Christensen again attested to her competence when Brooke created the Anthony Marshall Fund. No one doubted that she was dramatically diminished. But often she seemed able to hold up her end of conversations. In February 2004, Freddy Melhado, Brooke’s longtime friend, dancing partner, and a supervisor of a significant part of her money, attended a luncheon at the Knickerbocker Club. Brooke read a good-natured 110-word speech thanking Tony for “what he has achieved managing my financial affairs.” Her physician, Dr. Rees Pritchett, also in attendance, doubted that Brooke could have composed that speech. She might have been able to read a text, but could she interrelate facts, process abstract concepts? Still, to Melhado, she seemed alert that day.

Tony didn’t take advantage of his failing mother, he says. Strong-willed Brooke knew what she wanted: to get him “everything.” The problem was that Christensen was dragging his feet. He’d taken almost a year to implement the Anthony Marshall Fund. It had also taken a year to transfer Cove End. “It was late in the game,” Tony says.

At this point a lawyer named Francis X. Morrissey Jr., a soft-spoken Harvard man whom Charlene had met in Maine a couple of decades earlier, entered the picture. Tony thought him generous and intelligent. Morrissey helped Tony and Charlene with their theater projects. He was involved with Charlene’s charity, Shepherd Community Foundation, which Brooke supported with a gift of $100,000. They say they didn’t know that Morrissey had for two years been suspended from the bar for an unauthorized withdrawal from a client’s account. “A shock,” says Tony. They knew he was kind, a friend to those in need, the elderly in particular, some of whom turned out to be rich. For his elderly clients, Morrissey seemed to always be there. He supervised health care, dressed them, even took them to the bathroom. “The best thing he would do,” remembers Charlene, “he would take them for lunch once a week just to make them feel loved and humanized and that someone cared about them. Francis has a very soft heart.”

Charlene says she didn’t know that he also had a knack for ending up in their wills. A woman from Maine left him 29 acres of choice Maine property. One man changed his will the day before he died, leaving Morrissey a Manhattan apartment. Morrissey was bequeathed a couple of Renoirs. The wealthiest of his clients once said Morrissey should have all of her $15 million estate.

Brooke had long enjoyed Morrissey’s company (she’d met him independently). They talked books; he sent her volumes to read and also flowers. In 2000, she thanked Morrissey for that “lovely floral bouquet you sent me—it was so dear of you,” and for their conversations. “As ever devotedly,” she signed. Or, “as ever with love.” Morrissey escorted Brooke to the opening night of Tony’s plays.“In the course of knowing and seeing him she became very comfortable talking to him,” says Tony.Charlene recalls, “For months, Brooke said to Francis, ‘I’m worried about Tony. I’m worried about his finances.’ ” Finally, Morrissey told Charlene and Tony, “Look, this poor woman is suffering. This is what she really wants to do.” He meant, Get Tony the money. And Christensen wasn’t moving.“Everybody finally decided it had to be done,” says Charlene. Christensen was Brooke’s lawyer; it wasn’t Tony and Charlene’s will, but something had to be done. This is what Brooke wanted. Morrissey was hired.

And so at tea time on January 12, 2004, Morrissey was seated in Brooke’s red-lacquered library. Brooke wore a smart blue suit, lovely against the red Louis XV chairs. Tony, in his usual coat and tie, joined them. Morrissey had hired G. Warren Whitaker, an estate lawyer with solid credentials from Day, Berry & Howard. Morrissey knew what Brooke wanted; Whitaker provided drafting experience. (Tony and Charlene let Christensen go the following month.) In Whitaker’s account of the meeting, he and an associate arrived at 4:15. Tony—to Whitaker, he is Ambassador Marshall—greeted them, then left.Morrissey handed Brooke the codicil to her will, which Whitaker had drafted.“Good,” she said. “I am not going to be around much longer.”She read the document, reading parts aloud.

In previous wills, Tony had received an annual stipend; in 2002, it was 7 percent of what remained of Brooke’s personal money after bequests, perhaps $50 million. When Tony died, the remainder was to go to charity. In 2003, Brooke had pronounced herself satisfied with that arrangement. In this codicil, Tony gets it all in one lump sum and, for the first time, Morrissey explained to Brooke that Tony can leave property to his wife, “deranging,” Chase claimed, her long-established testamentary plans.

Whitaker may not have met Brooke before, but to him she seemed cogent. That afternoon, according to his memo, Brooke said, “They are happy?” She’s referring to Tony and Charlene. She often made the same comment to friends. That afternoon she phrased it as a question. Morrissey assured her they were.

“Are they happy in bed?” asked Brooke. Everyone laughed. Morrissey handed her a pen. “Should I sign Russell?” she asked, referring to her maiden name. She thought for a moment. “Tony likes me to.”Tony was thrilled by the change. “I was delighted she was giving it to Charlene,” he says. Charlene contemplates the fortune. “It would be wonderful,” she says. “It’s not going to change my life. I would give a hell of a lot of it away.”Of course, they know that others think they are taking advantage of Brooke; that they are stealing. In fact, Annette, who was bequeathed four dog paintings from Brooke, has asked the court to invalidate every will after 1997.

“The only word that comes to my mind is jealous,” says Charlene.“That we’re happy,” says Tony.“That Brooke and I did get along so well,” says Charlene.Two months later, in March 2004, Brooke signed a third codicil, which calls for her estate to sell Brooke’s properties before distributing the proceeds. It may have been a tax-planning measure, but it raises suspicions. Tony, now sole executor of Brooke’s estate, has named Morrissey and Charlene co-executors of the estate. The executors will benefit through increased fees. Whitaker didn’t attend this session. He had a scheduling conflict; an associate didn’t have a tie. Morrissey told him casual dress would be disrespectful. He didn’t come either. Morrissey is the supervising attorney and the notary on the document, which a handwriting expert later said couldn’t have been signed by Brooke.

For at least a decade, Brooke had planned her own funeral. She designated the hymns to be sung, and wrote a guest list. She put Tony in charge. Annette’s guardianship lapsed with Brooke’s death; a judge declined to appoint her administrator of the estate after Tony’s lawyer argued she would “pursue the vicious and self-aggrandizing vendetta.” Brooke expected her many friends to pack St. Thomas Church. Instead, many in Brooke’s crowd boycotted Tony’s event. For Tony and Charlene, it has become a painful and angry time. Tony’s health suffers; Charlene fears he may not survive the stress (it’s a threatening time, too; the grand jury could hand down indictments soon). Brooke’s generosity is contested, Tony’s reputation derided. Tony detests his son. Brooke’s friends detest Tony and Charlene. And others now claim Brooke’s loyalty and love. Tony knows his mother loved him—he consoles himself with thoughts of her. He thinks sometimes of the last months of her life.

Annette had moved Brooke to Holly Hill, where she was sure Brooke wanted to be. Annette had brought the dogs and filled the house with flowers, upstairs and down. Tony visited, providing the hour’s notice required by Annette. He sat in his mother’s bedroom. Mostly, she slept. Tony could see that her eyes were sunken. Still, her makeup was done. The staff applied eye shadow and cleaned her breathing tube. “More blue,” she’d tell the nurses, one of her last phrases. Tony held her hand. Sometimes Brooke’s arm or a leg moved involuntarily. It was hard not to think it was willful, as if she were trying. Tony talked to her. And sometimes Brooke muttered something. “I love you,” Tony is sure she said, which filled him with emotion. It was a thing she sometimes said in her last year to people in her life.

Additional reporting by Andrea Fjeld, Michelle Dubert, Catherine Coreno, and Sadia Latifi.