Peter Sheehy, a history teacher at the Horace Mann School, sat in his bedroom, trolling the Internet. It was the fall of 2006, shortly after lunch on a Saturday afternoon. The school year had just begun. Not a good start, Sheehy thought. On Thursday, J.T. Della Femina, the newly elected student-body president and son of advertising magnate Jerry Della Femina, had brought a female club leader to tears at the opening high-school assembly when he introduced her at the podium as “the Queen of Mean.”

Now, in the hallways and in the school newspaper, students and teachers were fiercely debating the presence of sexism on campus. The students defended J.T.’s words even as the teachers deplored them.

MYSPACE, Sheehy typed into Google. He had never been on social-networking sites before, but he was troubled by the reaction to the assembly, and his worry triggered a thought. Not long ago, a student had told him that classmates were photographing a math teacher with their cell phones and posting the embarrassing pictures online. (Sheehy was chairman of the faculty-grievance committee.) Perhaps it was worth taking a look.

Logging on to MySpace proved too complicated, but then he recalled a faculty seminar he’d attended the previous spring, in which Adam Kenner, Horace Mann’s technology director, had demonstrated how to monitor student Facebook pages. All it took was a Horace Mann e-mail account, a false name, and a year of graduation. Following Kenner’s lead, he logged on to Facebook using middle names. Sheehy found no evidence of the photos but within a few minutes stumbled on something much worse.

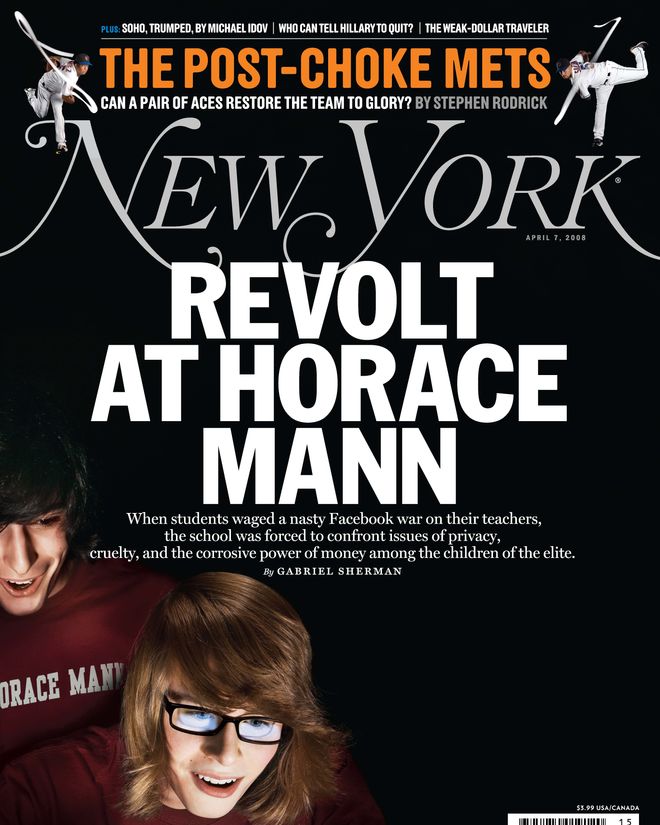

Cover Story

The Web page for a Horace Mann Facebook group titled the “Men’s Issues Club” mocked a student organization on campus called the Women’s Issues Club. The 44 members of the parody club included children of both trustees and the legion of prominent names who send their children to Horace Mann, which sits in the top rung of private schools in New York. One club member referred to an English teacher as a “crazy ass bitch” and a French teacher as an “acid casualty.” Another boy boasted that he’s “the only person here who actually beats women when hes [sic] drunk. no joke,” while still another bragged that he had “banged” a teacher “in [the] music dept. bathroom” and “will get great college rec” for the accomplishment. The boys lamented Star Jones’s “fat and wrinkled ass,” “sex in the city,” and “feminism,” proclaiming, “WHERE DO THEY BELONG?!?!????!!! IN THE KITCHEN!! IN THE KITCHEN!!!” The club summed up its mission thus: “For too long men have not had a way to express themselves and their beliefs in society. Men need to have a voice, we aren’t meant to be seen and not heard. Let freedom ring, bitches.”

Shocked, Sheehy continued trolling. He then found a Facebook Web page for “McGuire Survivors 2006,” a student group dedicated to his colleague, Danielle McGuire, a 33-year-old history instructor with a liberal bent who had taught at Horace Mann for a year. The page’s profile picture was a grotesque illustration of the black slave Tituba, one of three women first accused in the Salem witch trials. Scrolling down the page, Sheehy again found trustee children behind the Website. Derogatory slogans about McGuire included “Official Minority Rights Officer and Head of Protection for Feminist Society” (McGuire is white) and “Representation of Oppressed ‘Indians’ of America.” The club called on prospective members to join if “you know what it is like to be a McGuireite; you have an entire volume of doodles in your history notebook; you have never done the reading; you are scared to enter history class for fear of brainwashing,” concluding ominously, “you don’t know if you will leave class alive.”

Horace Mann has always been a pressurized place, the junior division of New York’s elite. Parents of current students include former governor Eliot Spitzer, Hillary Clinton pollster Mark Penn, fashion designer Kenneth Cole, and Sean “Diddy” Combs. But the Internet has added a new kind of pressure. For Horace Mann, this new reality emerged in the winter of 2004, when an eighth-grader e-mailed a cell-phone video of herself masturbating and simulating fellatio on a Swiffer mop to a boy she liked, who in turn forwarded the clip to his friends. In short order—as these things inevitably do—the video popped up on Friendster for millions to view. “Swiffergate,” as the scandal became known, roiled the Horace Mann community.

Adam Kenner, who had taught in the school’s technology department for twenty years, began lecturing parents, students, and teachers on the risks of social networking. “Nothing online is private, not even if you are only sharing it with your best friend,” he said in one speech. “Don’t post anything online you wouldn’t want posted on a bulletin board in your school’s hallway.”

These Facebook pages, however, were something different. Kids have always ragged on an unpopular teacher or ridiculed an unfortunate classmate. But sites like Facebook and RateMyTeachers.com are changing the power dynamics of the community in an unpredictable way. It is as if students were standing outside the classroom window, taunting the teacher to her face. Should they be punished? There were, as yet, no rules or codes for how a school should address such issues. (Horace Mann, through its PR advisers Kekst and Company, declined to comment.)

But the questions provoked by the Web postings ran deeper than these. Who should make the rules? In the past, there had been at least a rough assumption that teachers were parental surrogates, authority figures who were charged with making decisions regarding education and discipline, and that the rules governing this kind of behavior were clearly the faculty’s to make. But the frenzy around college admissions is driving a private-school arms race, funded by wealthy parents who believe their contributions entitle them to substantial input in the running of the schools. Now, at times, teachers can seem merely like hired help. Horace Mann alumnus William Barr, the U.S. attorney general under President George H.W. Bush, believes that the school has become “too much of a business.” “The school needs and wants a lot of money,” he says, “so the influence of the business community becomes very strong. It’s a symbiotic relationship. But in the long run, the school loses something.”

The students were more aware than ever of where the real power resided. So when the Facebook situation was brought into the open, the teachers found themselves powerless to act, and the students did not passively wait to be disciplined.

Sheehy knew the Facebook pages had the potential to be explosive. The previous spring, the board had been furious with a colleague of Sheehy’s in the history department, Andrew Trees, after he published a satirical novel about an unnamed New York City private school (bearing a strong resemblance to Horace Mann) and its craven and corrupt board of trustees. Around the time Trees admitted in a letter to the Horace Mann student newspaper that he was the author of Academy X, some board members wanted him fired.

On Monday morning, September 25, 2006, Sheehy alerted Thomas M. Kelly, the head of school, to the Facebook clubs, and Kelly called an emergency meeting after school, attended by the grievance committee and department heads and deans. Within hours, several board members’ children were pulled off the Web pages. It was becoming clear that this was something the powers at the school would rather sweep under the table.

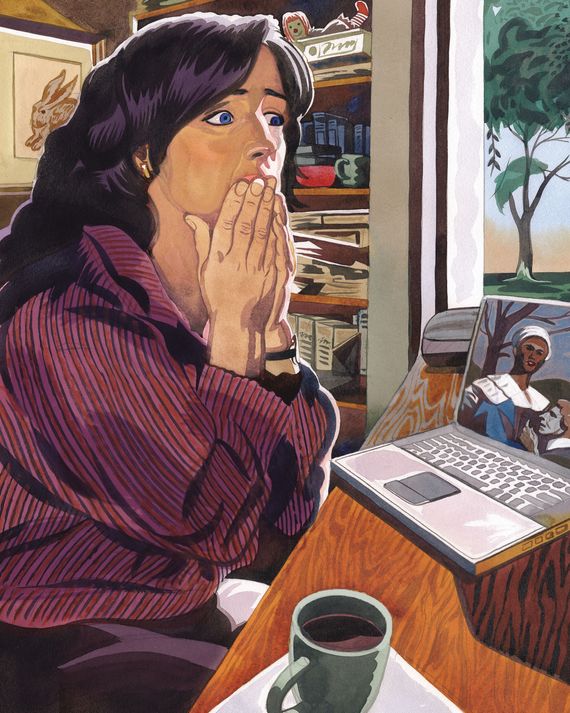

Meanwhile, the history department informed Danielle McGuire about the club specifically targeting her. From her computer in the history-department office, she logged on (using her married name) and stared at the screen, aghast. Immediately, she recognized the crude illustration of Tituba, whom she had lectured on last year. Tituba as Aunt Jemima, she thought. The artist had painted a racial slur. In every word on the page, McGuire saw herself depicted as a witch or a bitch. She trembled a little as she read the names of the members. There was the daughter of one board member, who had e-mailed from her daddy’s BlackBerry requesting extra credit. And the club’s creator, who daydreamed in class. (The Facebook page sometimes seemed to have been written not so much to attack the teacher as to express admiration for a boy she liked. “I formally dedicate this group to … a survivor (hopefully) and a friend,” she wrote. “Didn’t think he was going to make it, but he pulled through and got a hug!”) And a rich kid who got caught up in the wrong crowd. And then, McGuire saw the name that bothered her most. We’ll call him Jeffrey Robbins.

Jeffrey was McGuire’s most antagonistic student from sophomore U.S. history the previous year. Jeffrey challenged McGuire’s focus on liberal politics and civil rights, proposing to write his class research project on plagiarism in Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches and saying that his hero was Roy Cohn—himself a Horace Mann alumnus. The previous spring, after he lost a student-judged essay competition, Jeffrey had stormed into the history-department office, railing against McGuire’s sexism and claiming she was biased against his work. A few weeks later, Jeffrey accused McGuire of maligning his mentor, Sam Gellens, a more conservative world-history instructor, in class. The school investigated and found no evidence to substantiate his claims.

On Tuesday afternoon, September 26, McGuire informed Barbara Tischler, the high-school principal, that she viewed the Facebook group as connected to Jeffrey’s earlier conflicts with her. The page had exhorted students to join McGuire Survivors if “your name is Jeffrey Robbins” and “you are excited to enter history class to see Jeffrey Robbins pace around and get angry.” Clearly, Jeffrey was behind the group, McGuire explained, as Tischler listened impassively.

At a faculty meeting in the cafeteria after school the next day, Kelly said that punishments for students would be severe—and then proceeded to castigate the faculty for engaging in “similar behavior” by logging on to the Websites surreptitiously, and instructed them to straighten their “moral compasses.” “Your contracts are under review, and you’re being watched by the kids,” he said.

To McGuire, this was a shocking statement on a number of levels. She too had been at Kenner’s seminar the previous spring—as had the high-school principal and almost the entire faculty—and McGuire had followed his instructions in accessing Facebook. Kelly, however, didn’t acknowledge that the meeting had taken place—and thus that the administration had in effect sanctioned McGuire’s tactic. Instead, he tried to suggest that such ugliness was part of the job—he spoke of a time when, in his previous job as a public-school superintendent in Westchester County, he had been the target of online hate groups. Three times Kelly repeated that he had been called a “nigger lover.”

Kelly had been at Horace Mann for just over a year when the Facebook scandal erupted, and he hadn’t earned the trust of large segments of the faculty. What is clear is that Kelly, in the Academy X affair, had shown a keen grasp of the principles of political expediency. When Trees admitted to Kelly that he had written Academy X, Kelly was forgiving, urging him to announce the news in a letter to the school’s student newspaper, the Record. “I want to be clear that I have not tried to paint a portrait of Horace Mann,” Trees wrote. “Dr. Kelly has already read the book, and he assured me that he did not think it would cause any major problems.” Then, around the time the letter appeared in the paper, some members of the board leaned on Kelly to fire Trees. In early May, Kelly called Trees, Sheehy, and Barry Bienstock, chair of the history department, to his office for a meeting. “Just so you know,” Kelly began, “the pushback—I said that there’ll always be some—has occurred.”

“For me personally, and as head of the school, it’s satire,” Kelly told Trees and his colleagues gathered around Kelly’s conference table. “It’s fair game. It’s my job. I get criticized, and if you don’t want to be criticized, then you know what, live in a hole.” C’est la vie, in other words. “At this point in time the school does not see a legal issue … We’re going to handle this like everything else we handle here: by the book, standard operating procedure.”

His only concern, in fact, was the likely media frenzy the book would prompt. Kelly pledged to remind faculty not to talk to the press, invoking the “Swiffer incident.” The student newspaper’s review of the book would be the most delicate. “Everyone is trying to find out if I’m going to squash a Record review … I said, ‘It’s not my place.’ ” Kelly added, however, that he planned to put the Record’s archives behind a private firewall as soon as he could, but not now. “Just because your book is out,” Kelly confided. “It would look creepy.”

Despite his assurances, Kelly stressed that the board would not be so forgiving. “It’s frustrating to some trustees because in the corporate world, you don’t need cause, you just fire people,” he cautioned. “I’m trying to referee there. I said, ‘Guys, take a deep breath. With all the things going on, this is a book written by a faculty member that’s not unlike other things that have been written,’ ” Kelly said. He even played with the idea of writing a Horace Mann tell-all himself. “They’re nervous about me because I joked with one of them. I said, ‘What, are you kidding me? I only have two years left on my contract here, I’ll do Academy X uncensored!’ And they’re like, ‘That’s not funny.’ And I’m like, ‘Guys, think about it! David Schiller’ ”—the English-department chair, who became high-school principal last year—“ ‘says it all the time, and he’s right: There’s no better story than a Horace Mann story.’ And someone says, ‘Tom, what if you get hijacked by the media?’ I said, ‘Then my response to Larry on Larry King Live will be, “I just got here, I’m trying to clean this shit up.” ’ ”

Despite the pressure from the Horace Mann board, Trees remained on the payroll and returned to teach in the fall of 2006. In one way, his presence on campus further complicated the Facebook crisis: If a teacher could write what he wanted without punishment, why should students be disciplined for posting to sites that weren’t intended to be public? Even before being directly confronted by the administration, many students seethed at the perceived violation of their privacy. And in their fury, of course, the students had powerful allies: their own parents on the board. “It wasn’t just that students were threatened by the faculty; the faculty was threatened by the students,” the then–student-body vice-president, Michael Marcusa, recently recalled. “There was an erosion of trust.”

“We all knew which teachers were on Facebook, and that made it awkward to be sitting in class with them,” says Sonya Chandra, former editor-in-chief of the Record and member of another derogatory Facebook club.

On Thursday morning, September 28, Tischler sent an e-mail to the entire high school calling for a mandatory assembly on Friday to discuss the Facebook incident. “Make no mistake,” she wrote. “This is a serious issue, and there will be consequences for some students.”

That morning, Kelly called Sheehy to his office and said he was getting more pushback from board members, who were demanding that faculty be disciplined for accessing their children’s Facebook pages. After the meeting, Sheehy called his lawyer. Then a senior, who hadn’t viewed the sites himself, submitted a letter to the Record criticizing McGuire and another teacher for accessing the Facebook pages. Having learned that she was named in the letter, McGuire e-mailed Kelly and a dean who oversaw the paper hours before the newspaper was set to close, warning that she would sue for defamation if the letter appeared in print. Later that afternoon, Sheehy sent Kelly a memo from the grievance committee pressing him to censor the letter and protesting the board’s involvement. “We have been concerned by the involvement of [a member of] the Board of Trustees, in a disciplinary matter involving one of his children,” Sheehy wrote. “We consider this a clear conflict of interest and we trust that you will urge [the trustee] to allow the school to exercise its disciplinary responsibilities in relationship to its students.”

Kelly didn’t respond to the complaint regarding the trustee but commanded the Record to hold the letter.

At the Friday-morning assembly the next day, Kelly stressed the need to begin a dialogue about appropriate speech. At the same time, the trustees convened on campus.

Then, after lunch, McGuire and Sheehy were walking in front of Tillinghast Hall when a woman wearing alligator sunglasses stormed up to them. It was the trustee whose daughter had formed the anti-McGuire club.

“You logged into Facebook under a false name,” the woman said, glaring at McGuire.

“I had a right to defend myself against defamation,” McGuire responded.

“Students are just blowing off steam,” the trustee said. “They’re very stressed; it’s not unusual for them to say racist and sexist things … The site is private.”

“No,” McGuire insisted, “it’s got 9 million users.”

“What you did was like breaking into my daughter’s room and reading her diary … ”

“No,” McGuire said, the emotion rising in her voice, “what your daughter did was the equivalent of posting something in Times Square.”

McGuire could not control herself any longer. “What your daughter did was actionable, and I’m not talking about this anymore,” she said before walking off.

Barry Bienstock, the history-department chair, walked over as McGuire walked away. The trustee was seething. She told the men that McGuire had called her daughter’s friend Jeffrey Robbins, who is Jewish, a “Nazi” in class the previous spring and encouraged them to investigate the matter.

Over the next weekend, the administration became concerned that the media had gotten a whiff of the scandal. On Sunday, October 8, Tischler e-mailed the faculty, pressing them not to talk to reporters. “Last Friday, a member of the HM community—a faculty member, student, or staff member—called the Daily News to discuss matters that are being addressed in the Upper Division through disciplinary action for students and continuing conversation with faculty,” Tischler wrote. “In all instances of press inquiries, our response should be ‘no comment.’ ”

The following Tuesday, October 10, Kelly and Tischler called McGuire into a meeting. Tischler accused McGuire of “tearing the community apart” by viewing Facebook. Kelly added that the board chairman wanted her to write a letter to the Record explaining her actions. This was part of Jeffrey Robbins’s campaign to harass her, McGuire protested. Kelly replied that, in fact, there was a new allegation—the one leveled by the trustee in front of Tillinghast Hall—that McGuire had called Jeffrey a “Nazi” in class. “I hate to tell you this,” Kelly said, “but there is a rumor of a tape.”

That night, McGuire sobbed. As a senior in college, after setting out to study world religions, she had decided to convert to Judaism. She had been married for a year now to a Jewish doctor at Bellevue. How could she be accused of anti-Semitism? A working-class girl from rural Wisconsin, she had earned a doctorate from Rutgers. Her essay “It Was Like All of Us Had Been Raped,” about sexual violence in the civil-rights era, was anthologized in Best American History Essays 2006. But none of that seemed to matter. Before going to bed, McGuire wrote Bienstock. She was afraid to come to work, she confided.

Back at school the next morning, McGuire burst into tears during class and went home early. Bienstock e-mailed Kelly. Jeffrey better produce the tape or back off, he wrote. That evening, Kelly called McGuire and told her that the rumors of a tape were unfounded. Before hanging up, Kelly expressed his unwavering support to McGuire.

On Friday, the Record ran McGuire’s letter. Instead of expressing contrition, as the board chair had wanted, McGuire defended herself. “I make no apologies for integrating race and gender into my classes,” she wrote. “I should point out that all the other U.S. History teachers do the same—apparently without being ridiculed. To single me out is revealing, and is a sign that parts of the Horace Mann community are not as enlightened as they pretend to be … Instead of taking stock of the damage done to the community by these postings, some students, with the implied consent of some adults in the community, shifted the blame, cried victim, and wrapped themselves in rights they are not entitled to.” She concluded: “Is there anything more adolescent and intellectually craven than this?”

In November, the school cleared McGuire of making anti-Semitic remarks. Two weeks later, the administration doled out punishments. Except for the creator of the “Men’s Issues” club, who withdrew from the school, the involved students received slaps on the wrist. Two kids served one-day suspensions; the rest were asked to say sorry. The creator of the anti-McGuire club apologized to McGuire profusely in person. In a memo to the faculty, the deans acknowledged the administration’s slow response. “As we move ahead from the Facebook ‘episode,’ ” they wrote, “we recognize that our challenge to create an environment in which such behavior does not occur again has only begun.”

If the new rules of the Internet were some of the forces that were creating chaos in the Horace Mann community, another, unquestionably, was money. For much of the past decade, Horace Mann’s central preoccupation, like that of many private schools, has been fund-raising. In 1998, the board, then chaired by Michael Hess, a onetime partner at the white-shoe law firm Chadbourne and Parke (and a founding partner of Rudy Giuliani’s consulting firm), launched the most ambitious expansion in the school’s history. The master plan for the school’s eighteen-acre Riverdale campus included designs for a 45,000-volume library, a 640-seat theater, a renovated middle school, a new cafeteria, and an outdoor “Shakespeare Garden” planted with flora referenced in the playwright’s works.

Horace Mann’s endowment was $60 million at the time, but the construction budget topped $100 million. To finance the project, the school floated $103 million in bonds certified by the city’s Industrial Development Agency over the next five years. According to documents filed with the IDA, Horace Mann’s total debt will reach $339 million, including principal and interest, over the 42-year life of the bonds. The board has since raised tuition (now $29,000) and has completed two major fund-raising campaigns, including selling the naming rights to its new buildings (lockers at $500,000, computer classrooms $150,000 a pop, the orchestra pit for $250,000).

One consequence of the debt has been the consolidation of wealth on the board. The last full-time educator to serve as a trustee, Barnard dean Marjorie Silverman, left the board in 1999. Nowadays the board is dominated by lawyers, investment bankers, and real-estate developers, and, possibly as a consequence, the school’s relations with its teachers have suffered.

In the fall of 2004, the board informed Horace Mann teachers that financial pressures would require a cut in their health insurance. (According to tax filings, Horace Mann spent $7.2 million on faculty benefits in 2004, a little more than the $5.7 million financial-aid budget. That year, the school’s payments on construction reached $7.3 million.) In one tense meeting in November 2004, Steven Friedman, then board treasurer, chided the instructors for making “poor consumer choices” with their health coverage (citing Celebrex, the popular but costly arthritis drug). If they would not downgrade their health plans, the board might be forced to cut financial aid, he said. Following the meeting, a long-serving photography teacher sent a letter to then–board chair Robert Katz, Goldman Sachs’ general counsel, and the faculty objecting to the cuts. “I can’t begin to tell you how many faculty members I’ve heard wonder that baseball diamonds are more important than faculty health in the long-term future of the School,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, the board was facing resistance from faculty during the search for a new head of school. In April 2004, Eileen Mullady, who had run Horace Mann since 1995, announced she was leaving to run a private school outside San Diego. The board told faculty that they could have an advisory role but would have no voting rights in the final selection. Some faculty members bristled at the board’s secrecy, circulating a petition that protested the search. The board rejected the entreaties and narrowed the initial pool of candidates down to four finalists.

Just as the board announced benefit cuts, the first finalist in the head-of-school search arrived on campus for interviews. Of all the candidates, Kelly, who’d been superintendent of the Valhalla school district in Westchester, stood out for his lack of private-school experience. He had spent the first ten years of his career teaching children with severe mental handicaps before becoming a public-school administrator. But the board was impressed with his experience running a large, complex school system and his experience with construction, though things had not always gone as planned. In 2003, Kelly had allowed construction companies to dump debris at Valhalla schools in exchange for building new athletic fields atop the pile, but the plan backfired. (A 2005 report published by State Comptroller Alan Hevesi found that the “fill-for-fields” scandal was a “windfall for the construction companies that saved as much as $19.4 million in dumping fees but a disaster for taxpayers who must pay nearly $3.8 million” to clean up the mess.) At the time Kelly told the Westchester Journal News, “You have to come and see what we’ve gotten: two new baseball fields and synthetic turf on another. That’s how I rationalize what a nightmare this has been.”

After the board had interviewed the candidates, Peter Sheehy and Jennifer McFeely, head of the guidance department, met with Katz to recommend that the school continue its search. On January 5, 2005, the board announced that the job had gone to Kelly. Over lunch that day, David Schiller told Sheehy, “This is a tragic day for Horace Mann.”

Andrew Trees remained on the sidelines during the Facebook imbroglio. A month after the scandal, however, David Schiller, Trees charges, told a colleague that Kelly had claimed Trees was at work on a second book, this time a nonfiction exposé of Horace Mann. (Trees later explained that he was writing a book, but its subject was the science of dating.) Schiller’s allegations baffled Trees, but because no administrator had confronted him directly, he did not bother to set the record straight.

On Sunday, January 28, 2007, Kelly informed Barry Bienstock that he would not be renewing Trees’s contract; in effect, he was being fired. (Faculty who pass a performance review after three years of teaching are granted automatic contract renewals, and the school’s handbook outlines a process for termination. Trees had been at the school for six years and had never been afforded a formal dismissal process.) The next afternoon, Kelly told Trees that he was “a really great teacher” and the school had “no complaints” about his professionalism. But hypothetically speaking, Kelly wouldn’t offer a job to a teacher if he knew the applicant was writing a “satirical review” about the school. Therefore, Kelly was giving Trees the option to resign. If he didn’t accept? “I don’t know what I’ll say to people when they call and ask why we’re not keeping you,” Kelly said.

Later that week, Sheehy and the three other members of the faculty-grievance committee resigned their positions in protest. In March, Trees’s attorney, Ed Little, met with the school’s lawyer, Mark Brossman, and vice-chairman of the Horace Mann board, Cahill Gordon & Reindel partner Howard “Peter” Sloane. Before Little could open negotiations over severance, Sloane cut him off. “The answer is zero,” he said. “Maybe we’ll give him a letter of recommendation, but he’s out.”

News that Trees was leaving was closely held. Over the spring, he quietly packed up his office, bringing a few books home each day. But on Friday, May 18, Sheehy wrote a letter to the Record disclosing Trees’s departure. “The short-term satisfaction that some may receive by the expulsion of Dr. Trees from our community will, I fear, be overshadowed by the chilling effect that such an act will have on the open and free exchange of ideas that is crucial to a secure and healthy institution,” he wrote. Some students protested Trees’s firing. One class studying civil disobedience staged a walkout, and enlisted another—studying Bolshevik history—to walk out, too. But other students had somewhat subdued reactions. (In the Record the previous spring, a snide, un-bylined review had noted that Academy X “leaves HMers wondering just how much of the book is real—and I’m sure that we all hope that the explicit sexual urges that teachers in Academy X feel towards their students and co-workers are more fictional than the large bell tower that Trees describes as adorning the school.”)

Students questioned once again why the same teachers who had cracked down on student expression on Facebook were now defending the free speech of a colleague who had made fun of students in his novel. “When it was students saying things about teachers—and I’m not equating—they were immediately punished,” said Jessica Moldovan, a member of the class of 2007. “And when it was a teacher making certain statements about students, about the way we act, many of which were fabricated and exaggerated, you know, he was fighting back and saying freedom of speech.” Other students complained about teachers who passed around petitions in class defending Trees. “It was borderline coercive,” said Michael Marcusa, then student-body vice-president. “The overall principle of trying to bring students into a dispute with the administration is unprofessional.”

The week before final exams, Sheehy collected signatures from some 60 scholars and public figures on a petition voicing support for Trees, and submitted it to the Record. After the editors called Kelly for comment, he censored the letter, citing legal grounds.

On graduation day, last June, Trees packed up his remaining books and left campus. Danielle McGuire, who sat two desks down from Trees in the history-department office, was also leaving. In March, Kelly informed her too that the school would not be renewing her contract. (She’s now on a fellowship at the University of North Carolina’s Center for the Study of the American South.) “The really good students make you forget about all the crap,” McGuire recalled recently. “Now when I go back through this, I can’t believe this shit … It was so clearly about the culture of money and power and lack of a willingness to really take a firm stand over what was right and wrong.” Martin Bienenstock, a Dewey & LeBoeuf partner whose son was in McGuire’s class, regrets the board’s decision. “The issue of privacy was misapplied totally,” he says. “After having heard what was said about her, she easily could have filed a lawsuit and gotten that material in discovery. She decided not to sue. Frankly, that was a concession on her part. Lots of lawyers would have taken that case.”

In November, Trees’s new attorney, Thomas Mullaney, filed a lawsuit in State Supreme Court against Horace Mann, alleging that the school’s firing of Trees violated its employment agreement. The suit also alleges that Schiller defamed Trees by falsely accusing him of drafting a nonfiction tell-all in the fall of 2006.

In February, Horace Mann’s lawyers filed a 121-page motion to dismiss, claiming that the school employs teachers on one-year contracts without any guarantees of renewal and that Horace Mann rightly didn’t renew Trees’s contract, since he had embarrassed the school in a work of fiction. “Reaction in the School community to the portrayal of ‘Horace Mann’ in Academy X once the book was published was swift and overwhelmingly negative,” Kelly said in an affidavit. “The School concluded that Trees’s continued employment, under the circumstances, would be divisive and distracting.” (In a meeting with Trees the previous May, Kelly said he had heard complaints “second- and thirdhand.”)

Reconciliation between Horace Mann’s students, faculty, and administration has been agonizingly slow to come. Last spring, the administration canceled the student elections after several candidates ridiculed classmates during campaign speeches. After the voting was halted, Jeffrey Robbins became a campus populist, railing against the teachers’ involvement in the election, and the administration decided to let the election proceed.

For his part, Peter Sheehy always planned to return for his ninth year at Horace Mann this school year. But in August, Kelly invited Sheehy to join him for lunch with David Schiller, the high-school principal. At the Mercer Kitchen, near the Soho loft that Sheehy shares with his wife, Us Weekly editor Janice Min, Kelly and Schiller informed Sheehy it was time for him to take a sabbatical, “paid or unpaid.” It wasn’t punitive, they claimed.

Over the next week, Sheehy and Schiller worked on the terms of the leave, with little progress. The night before teachers returned to school this fall, Schiller called Sheehy at home. “Look, let me just tell you, I have not gone over to the dark side, okay?” Schiller began. “I mean, Tom,” he said, referring to Kelly, “needs me to succeed in the school. And Tom likes me. I mean, maybe I should feel bad about that, but I don’t. I feel good about that because it’s going to help me change the school, okay?”

Sheehy pressed Schiller to sign a formal letter stating he could return to Horace Mann the next year or the school would pay out his salary. “I just feel I’m in a very highly unusual situation,” he kept repeating. “I need to be protected.”

Schiller countered that Kelly probably wouldn’t sign any such agreement. “You know, what’s going to be is going to be,” Schiller said. “It will take a lot of generations to undo the bad shit that has happened. But I have some ideas about how to begin. And they involve holding people to their commitments, they involve talking about values, they involve the dean of faculty, and they involve, you know, rules. And having people live up to the rules, because the rules come from our values. And I don’t think that has happened at Horace Mann.”

Sheehy needed more than lofty assurances. “You weren’t there when Tom promised Andy that his job was secure, waited a year, and instead of firing him, said, ‘Oh, I’m not renewing his contract.’ Okay, very cute, all right? And what happens next year when he says, ‘I’m not firing Peter; I’m just not renewing his contract’?”

“I’ll regard it as a betrayal of me,” Schiller said.

Schiller tried to buy time, telling Sheehy they could hammer out an agreement in the coming days. But Sheehy wouldn’t have it. If Horace Mann didn’t sign his letter, he would return to campus and teach that week. In that case, Schiller warned, the school would strip him of his teaching duties.

“I’m not paranoid,” Sheehy said. “Clearly some people wanted me fired, you can’t deny that.”

“I’m not denying that,” Schiller conceded.

Schiller added that even if Horace Mann let Sheehy go, he would remain loyal and write a letter of recommendation for him. “It’s not in Horace Mann’s interests that you should be trashed. It just isn’t,” he said. “I’ll write you the letter now, you can have it and put the date on it … Maybe Tom is harboring some deep, dark, evil idea, but I don’t think so. I would know. Now, if something becomes litigious during the year, you’d be well advised to have a conversation with him.”

“It’s amazing to look at the supposed brain power of the board, or at least their earning power, and try to figure out how they made some decisions,” Sheehy said, sighing.

“I don’t know what the hell they’re going to do, and they don’t answer to me,” Schiller replied.

The tension eased. Sheehy realized he had no choice but to take the sabbatical.

“I love you, and you’re my friend,” Schiller went on. “I don’t want to deprive you of the school. I really don’t. I know it means a lot to you. But I also have to think about the health of the upper school as a whole. And I think that it’s probably a good idea, given the situation, to let everyone step back and chill out, and not to be reminded of the shit that went down last fall”—Facebook—“or the shit that went down the previous spring”—Academy X. “We need to put that behind us and get a new piece of history.”

That week, Jeffrey Robbins assumed office as the newly elected student-body president.