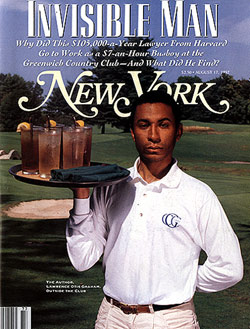

From the August 17, 1992 issue of New York Magazine.

I drive up the winding lane past a long stone wall and beneath an archway of 60-feet maples. At one bend of the drive, a freshly clipped lawn and a trail of yellow daffodils slope gently up to the four-pillared portico of a white Georgian colonial. The building’s six huge chimneys, the two wings with slate-gray shutters, and the white-brick façade loom over a luxuriant golf course. Before me stands the 100-year-old Greenwich Country Club—the country club—in the affluent, patrician, and very white town of Greenwich, Connecticut, where there are eight clubs for 59,000 people.

I’m a 30-year-old corporate lawyer at a midtown Manhattan firm, and I make $105,000 a year. I’m a graduate of Princeton University (1983) and Harvard Law School (1988), and I’ve written eleven nonfiction books. Although these might seem like good credentials, they’re not the ones that brought me here. Quite frankly, I got into this country club the only way that a black man like me could—as a $7-an-hour busboy.

After seeing dozens of news stories about Dan Quayle, Billy Graham, Ross Perot, and others who either belonged to or frequented white country clubs, I decided to find out what things were really like at a club where I saw no black members.

I remember stepping up to the pool at a country club when I was 10 and setting off a chain reaction: Several irate parents dragged their children out of the water and fled. Back then, in 1972, I saw these clubs only as a place where families socialized. I grew up in an affluent white neighborhood in Westchester, and all my playmates and neighbors belonged somewhere. Across the street, my best friend introduced me to the Westchester Country Club before he left for Groton and Yale. My teenage tennis partner from Scarsdale introduced me to the Beach Point Club on weekends before he left for Harvard. The family next door belonged to the Scarsdale Golf Club. In my crowd, the question wasn’t “Do you belong?” It was “Where?”

My grandparents owned a Memphis trucking firm, and as far back as I can remember, our family was well off and we had little trouble fitting in—even though I was the only black kid on the high-school tennis team, the only one in the orchestra, the only one in my Roman Catholic confirmation class.

Today, I’m back where I started—on a street of five- and six-bedroom colonials with expensive cars, and neighbors who all belong somewhere. As a young lawyer, I realize that these clubs are where business people network, where lawyers and investment bankers meet potential clients and arrange deals. How many clients and deals am I going to line up on the asphalt parking lot of my local public tennis courts?

I am not ashamed to admit that I one day want to be a partner and a part of this network. When I talk to my black lawyer or investment-banker friends or my wife, a brilliant black woman who has degrees from Harvard College, law school, and business school, I learn that our white counterparts are being accepted by dozens of these elite institutions. So why shouldn’t we—especially when we have the same ambitions, social graces, credentials, and salaries?

My black Ivy League friends and I talk about black company vice-presidents who have to beg white subordinates to invite them out for golf or tennis. We talk about the club in Westchester that rejected black Scarsdale resident and millionaire magazine publisher Earl Graves, who sits on Fortune 500 boards, owns a Pepsi-distribution franchise, raised three bright Ivy League children, and holds prestigious honorary degrees. We talk about all the clubs that face a scandal and then run out to sign up one quiet, deferential black man who will remove the taint and deflect further scrutiny.

I wanted some answers. I knew I could never be treated as an equal at this Greenwich oasis—a place so insular that the word Negro is still used in conversation. But I figured I could get close enough to understand what these people were thinking and why country clubs were so set on excluding people like me.

March 28 to April 7, 1992

I invented a completely new résumé for myself. I erased Harvard, Princeton, and my upper-middle-class suburban childhood from my life. So that I’d have to account for fewer years, I made myself seven years younger—an innocent 23. I used my real name and made myself a graduate of the same high school. Since it was ludicrous to pretend I was from “the streets,” I decided to become a sophomore-year dropout from Tufts University, a midsize college in suburban Boston. My years at nearby Harvard had given me enough knowledge about the school to pull it off. I contacted some older friends who owned large companies and restaurants in the Boston and New York areas and asked them to serve as references. I was already on a leave of absence from my law firm to work on a book.

I pieced together a wardrobe with a polyester blazer, ironed blue slacks, black loafers, and a horrendous pink-black-and-silver tie, and I set up interviews at clubs. Over the telephone, five of the eight said that I sounded as if I would make a great waiter. But when I met them, the club managers told me I “would probably make a much better busboy.”

“Busboy? Over the phone, you said you needed a waiter,” I argued. “Yes, I know I said that, but you seem very alert, and I think you’d make an excellent busboy instead.”

The maître d’ at one of the clubs refused to accept my application. Only an hour earlier, she had enthusiastically urged me to come right over for an interview. Now, as two white kitchen workers looked on, she would only hold her hands tightly behind her back and shake her head emphatically.

April 8 to 11

After interviewing at five clubs and getting only two offers, I made my final selection in much the way I had decided on a college and a law school: I went for prestige. Not only was the Greenwich Country Club celebrating its hundredth anniversary but its roster boasted former president Gerald Ford (an honorary member), baseball star Tom Seaver, former Securities and Exchange Commission chairman and U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands John Shad, as well as former Timex spokesman John Cameron Swayze. Add to that a few dozen Fortune 500 executives, bankers, Wall Street lawyers, European entrepreneurs, a Presbyterian minister, and cartoonist Mort Walker, who does “Beetle Bailey.” [The Greenwich Country Club did not respond to any questions from New York Magazine about the club and its members.]

For three days, I worked on my upper-arm muscles by walking around the house with a sterling-silver tray stacked high with heavy dictionaries. I allowed a mustache to grow in, then added a pair of arrestingly ugly Coke-bottle reading glasses.

April 12 (Sunday)

Today was my first day at work. My shift didn’t start until 10:30 A.M., so I laid out my clothes at home: a white button-down shirt, freshly ironed cotton khaki pants, white socks, and white leather sneakers. I’d get my official club uniform in two days. Looking in my wallet, I removed my American Express gold card, my Harvard Club membership ID, and all of my business cards.

When I arrived at the club, I entered under the large portico, stepping through the heavy doors and onto the black-and-white checkerboard tiles of the entry hall.

A distracted receptionist pointed me toward Mr. Ryan’s office. I walked past glistening silver trophies and a guest book on a pedestal, to a windowless office with three desks. My new boss waved me in and abruptly hung up the phone.

“Good morning, Larry,” he said with a sufficiently warm smile. The tight knot in his green tie made him look more fastidious than I had remembered from the interview.

“Hi, Mr. Ryan. How’s it going?”

Glancing at his watch to check my punctuality, he shook my hand and handed me some papers.

“Oh, and by the way, where’d you park?”

“In front, near the tennis courts.”

Already shaking his head, he tossed his pencil onto the desk. “That’s off limits to you. You should always park in the back, enter in the back, and leave from the back. No exceptions.”

“I’ll do the forms right now,” I said. “And then I’ll be an official busboy.”

Mr. Ryan threw me an ominous nod. “And Larry, let me stop you now. We don’t like that term busboy. We find it demeaning. We prefer to call you busmen.”

Leading me down the center stairwell to the basement, he added, “And in the future, you will always use the back stairway by the back entrance.” He continued to talk as we trotted through a maze of hallways. “I think I’ll have you trail with Carlos or Hector—no, Carlos. Unless you speak Spanish?”

“No.” I ran to keep up with Mr. Ryan.

“That’s the dishwasher room, where Juan works. And over here is where you’ll be working.” I looked at the brass sign. MEN’S GRILL.

It was a dark room with a mahogany finish, and it looked like a library in a large Victorian home. Dark walls, dark wood-beamed ceilings. Deep-green wool carpeting. Along one side of the room stood a long, highly polished mahogany bar with liquor bottles, wineglasses, and a two-and-a-half-foot-high silver trophy. Fifteen heavy round wooden tables, each encircled with four to six broad wooden armchairs padded with green leather on the backs and seats, broke up the room. A big-screen TV was set into the wall along with two shelves of books.

“This is the Men’s Grill,” Mr. Ryan said. “Ladies are not allowed except on Friday evenings.”

Next was the brightly lit connecting kitchen. “Our kitchen serves hot and cold foods. You’ll work six days a week here. The club is closed on Mondays. The kitchen serves the Men’s Grill and an adjoining room called the Mixed Grill. That’s where the ladies and kids can eat.”

“And what about men? Can they eat in there, too?”

This elicited a laugh. “Of course they can. Time and place restrictions apply only to women and kids.”

He showed me the Mixed Grill, a well-lit, pastel-blue room with glass French doors and white wood trim.

“Guys, say hello to Larry. He’s a new busman at the club.” I waved.

“And this is Rick, Stephen, Drew, Buddy, and Lee.” Five white waiters dressed in white polo shirts with blue “1892” club insignias nodded while busily slicing lemons.

“And this is Hector and Carlos, the other busmen.” Hector, Carlos, and I were the only nonwhites on the serving staff. They greeted me in a mix of English and Spanish.

“Nice to meet all of you,” I responded.

“Thank God,” one of the taller waiters cried out. “Finally—somebody who can speak English.”

Mr. Ryan took me and Carlos through a hall lined with old black-and-white portraits of former presidents of the club. “This is our one hundredth year, so you’re joining the club at an important time,” Mr. Ryan added before walking off. “Carlos, I’m going to leave Larry to trail with you—and no funny stuff.”

Standing outside the ice room, Carlos and I talked about our pasts. He was 25, originally from Colombia, and hadn’t finished school. I said I had dropped out, too.

As I stood there talking, Carlos suddenly gestured for me to move out of the hallway. I looked behind me and noticed something staring down at us. “A video camera?”

“They’re around,” Carlos remarked quietly while scooping ice into large white tubs. “Now watch me scoop ice.”

After we carried the heavy tubs back to the grill, I saw another video camera pointed down at us. I dropped my head.

“You gonna live in the Monkey House?” Carlos asked.

“What’s that?”

We climbed the stairs to take our ten-minute lunch break before work began. “Monkey House is where workers live here,” Carlos said.

I followed him through a rather filthy utility room and into a huge white kitchen. We got on line behind about twenty Hispanic men and women—all dressed in varying uniforms. At the head of the line were the white waiters I’d met earlier.

I was soon handed a hot plate with two red lumps of rice and some kind of sausage-shaped meat. There were two string beans, several pieces of zucchini, and a thin, broken slice of dried meat loaf that looked as if it had been cooked, burned, frozen, and then reheated.

I followed Carlos, plate in hand, out of the kitchen. To my surprise, we walked back into the dank and dingy utility room, which turned out to be the workers’ dining area.

The white waiters huddled together at one end of the tables, while the Hispanic workers ate quietly at the other end. Before I could decide which end to integrate, Carlos directed me to sit with him on the Hispanic end.

I was soon back downstairs working in the grill. At my first few tables, I tried to avoid making eye contact with members as I removed dirty plates and wiped down tables and chairs. I was sure I’d be recognized.

At around 1:15, four men who looked to be in their mid- to late fifties sat down at a six-chair table while pulling off their cotton Windbreakers and golf sweaters.

“It’s these damned newspeople that cause all the problems,” said Golfer No. 1, shoving his hand deep into a popcorn bowl. “These Negroes wouldn’t even be thinking about golf. They can’t afford to join a club, anyway.”

Golfer No. 2 squirmed out of his navy-blue sweater and nodded in agreement. “My big problem with this Clinton fellow is that he apologized.” As I stood watching from the corner of the bar, I realized the men were talking about Governor Bill Clinton’s recent apology for playing at an all-white golf club in Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Holt, I couldn’t agree with you more,” added Golfer No. 3, a hefty man who was biting off the end of a cigar.

“You got any iced tea?” Golfer No. 1 asked as I put the silverware and menus around the table. Popcorn flew out of his mouth as he attempted to speak and chew at the same time.

“Yes, we certainly do.”

Golfer No. 3 removed a beat-up Rolex from his wrist. “It just sets a bad precedent. Instead of apologizing, he should try to discredit them—undercut them somehow. What’s to apologize for?” I cleared my throat and backed away from the table.

Suddenly, Golfer No. 1 waved me back to his side. “Should we get four iced teas or just a pitcher and four glasses?”

“I’d be happy to bring whatever you’d like, sir.”

Throughout the day, I carried “bus buckets” filled with dirty dishes from the grill to the dishwasher room. And each time I returned to the grill, I scanned the room for recognizable faces. After almost four hours of running back and forth, clearing dishes, wiping down tables, and thanking departing members who left spilled coffee, dirty napkins, and unwanted business cards in their wake, I helped out in the coed Mixed Grill.

“Oh, busboy,” a voice called out as I made the rounds with two pots of coffee. “Here, busboy. Here, busboy,” the woman called out. “Busboy, my coffee is cold. Give me a refill.”

“Certainly, I would be happy to.” I reached over for her cup.

The fiftyish woman pushed her hand through her straw-blonde hair and turned to look me in the face. “Decaf, thank you.”

“You are quite welcome.”

Before I turned toward the kitchen, the woman leaned over to her companion. “My goodness. Did you hear that? That busboy has diction like an educated white person.”

A curly-haired waiter walked up to me in the kitchen. “Larry, are you living in the Monkey House?”

“No, but why do they call it that?”

“Well, no offense against you, but it got that name since it’s the house where the workers have lived at the club. And since the workers used to be Negroes—blacks—it was nicknamed the Monkey House. And the name just stuck—even though Negroes have been replaced by Hispanics.”

April 13 (Monday)

I woke up and felt a pain shooting up my calves. As I turned to the clock, I realized I’d slept for eleven hours. I was thankful the club is closed on Mondays.

April 14 (Tuesday)

Rosa, the club seamstress, measured me for a uniform in the basement laundry room, while her barking gray poodle jumped up on my feet and pants. “Down, Margarita, down,” Rosa cried with pins in her mouth and marking chalk in her hand. But Margarita ignored her and continued to bark and do tiny pirouettes until I left with all of my new country-club polo shirts and pants.

Today, I worked exclusively with the “veterans,” including 65-year-old Sam, the Polish bartender in the Men’s Grill. Hazel, an older waitress at the club, is quick, charming, and smart—the kind of waitress who makes any restaurant a success. She has worked for the club nearly twenty years and has become quite territorial with certain older male members.

Members in the Mixed Grill talked about hotel queen and Greenwich resident Leona Helmsley, who was on the clubhouse TV because of her upcoming prison term for tax evasion.

“I’d like to see them haul her off to jail,” one irate woman said to the rest of her table. “She’s nothing but a garish you-know-what.”

“In every sense of the word,” nodded her companion as she adjusted a pink headband in her blondish-white hair. “She makes the whole town look bad. The TV keeps showing those aerial shots of Greenwich and that dreadful house of hers.”

A third woman shrugged her shoulders and looked into her bowl of salad. “Well, it is a beautiful piece of property.”

“Yes, it is,” said the first woman. “But why here? She should be in those other places like Beverly Hills or Scarsdale or Long Island, with the rest of them. What’s she doing here?”

Woman No. 3 looked up. “Well, you know, he’s not Jewish.”

“Really?”

“So that explains it,” said the first woman with an understanding expression on her tanned forehead. “Because, you know, the name didn’t sound Jewish.”

The second woman agreed: “I can usually tell.”

April 15 (Wednesday)

Today, we introduced a new extended menu in the two grill rooms. We added shrimp quesadillas ($6) to the appetizer list—and neither the members nor Hazel could pronounce the name of the dish or fathom what it was. One man pounded on the table and demanded to know which country the dish had come from. He told Hazel how much he hated “changes like this. I like to know that some things are going to stay the same.”

Another addition was the “New Dog in Town” ($3.50). It was billed as knackwurst, but one woman of German descent sent the dish back: “This is not knackwurst—this is just a big hot dog.”

As I wiped down the length of the men’s bar, I noticed a tall stack of postcards with color photos of nude busty women waving hello from sunny faraway beaches. I saw they had been sent from vacationing members with fond regards to Sam or Hazel. Several had come from married couples. One glossy photo boasted a detailed frontal shot of a red-haired beauty who was naked except for a shoestring around her waist. On the back, the message said, DEAR SAM, PULL STRING IN AN EMERGENCY. LOVE ALWAYS, THE ATKINSON FAMILY.

April 16 (Thursday)

This afternoon, I realized I was doing okay. I was fairly comfortable with my few “serving” responsibilities and the rules that related to them:

When a member is seated, bring out the silverware, cloth napkin, and a menu.

Never take an order for food, but always bring water or iced tea if it is requested by a member or waiter.

When a waiter takes a chili or salad order, bring out a basket of warm rolls and crackers, along with a scoop of butter.

When getting iced tea, fill a tall glass with ice and serve it with a long spoon, a napkin on the bottom, and a lemon on the rim.

When a member wants his alcoholic drink refilled, politely respond, “Certainly, I will have your waiter come right over.”

Remember that the member is always right.

Never make offensive eye contact with a member or his guest.

When serving a member fresh popcorn, serve to the left.

When a member is finished with a dish or glass, clear it from the right.

Never tell a member that the kitchen is out of something.

But there were also some “informal” rules that I discovered (but did not follow) while watching the more experienced waiters and kitchen staff in action:

If you drop a hot roll on the floor in front of a member, apologize and throw it out. If you drop a hot roll on the floor in the kitchen, pick it up and put it back in the bread warmer.

If you have cleared a table and are 75 percent sure that the member did not use the fork, put it back in the bin with the other clean forks.

If, after pouring one glass of Coke and one of diet Coke, you get distracted and can’t remember which is which, stick your finger in one of them to taste it.

If a member asks for decaffeinated coffee and you have no time to make it, use regular and add water to cut the flavor.

When members complain that the chili is too hot and spicy, instead of making a new batch, take the sting out by adding some chocolate syrup.

If you’re making a tuna on toasted wheat and you accidentally burn one side of the bread, don’t throw it out. Instead, put the tuna on the burned side and lather on some extra mayo.

April 17 (Friday)

Today, I heard the word nigger four times. And it came from someone on the staff.

In the grill, several members were discussing Arthur Ashe, who had recently announced that he had contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion.

“It’s a shame that poor man has to be humiliated like this,” one woman golfer remarked to a friend over pasta-and-vegetable salad. “He’s been such a good example for his people.”

“Well, quite frankly,” added a woman in a white sun visor, “I always knew he was gay. There was something about him that just seemed too perfect.”

“No, Anne, he’s not gay. It came from a blood transfusion.”

“Umm,” said the woman. “I suppose that’s a good reason to stay out of all those big city hospitals. All that bad blood moving around.”

Later that afternoon, one of the waiters, who had worked in the Mixed Grill for two years, told me that Tom Seaver and Gerald Ford were members. Of his brush with greatness, he added, “You know, Tom’s real first name is George.”

“That’s something.”

“And I’ve seen O. J. Simpson here, too.”

“O. J. belongs here, too?” I asked.

“Oh, no, there aren’t any black members here. No way. I actually don’t even think there are any Jews here, either.”

“Really? Why is that?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I guess it’s just that the members probably want to have a place where they can go and not have to think about Jews, blacks, and other minorities. It’s not really hurting anyone. It’s really a Wasp club… . But now that I think of it, there is a guy here who some people think is Jewish, but I can’t really tell. Upstairs, there’s a Jewish secretary too.”

“And what about O. J.?”

“Oh, yeah, it was so funny to see him out there playing golf on the eighteenth hole.” The waiter paused and pointed outside the window. “It never occurred to me before, but it seemed so odd to see a black man with a golf club here on this course.”

April 18 (Saturday)

When I arrived, Stephen, one of the waiters, was hanging a poster and sign-up sheet for a soccer league whose main purpose was to “bridge the ethnic and language gap” between white and Hispanic workers at the country clubs in the Greenwich area. I congratulated Stephen on his idea.

Later, while I was wiping down a table, I heard a member snap his fingers in my direction. I turned to see a group of young men smoking cigars. They seemed to be my age or a couple of years younger. “Hey, do I know you?” the voice asked.

As I turned slowly toward the voice, I could hear my own heartbeat. I was sure it was someone I knew.

“No,” I said, approaching the blond cigar smoker. He had on light-green khaki pants and a light-yellow V-neck cotton sweater adorned with a tiny green alligator. As I looked at the other men seated around the table, I noticed that all but one had alligators on their sweaters or shirts.

“I didn’t think so. You must be new—what’s your name?”

“My name is Larry. I just started a few days ago.”

The cigar-smoking host grabbed me by the wrist while looking at his guests. “Well, Larry, welcome to the club. I’m Mr. Billings. And this is Mr. Dennis, a friend and new member.”

“Hello, Mr. Dennis,” I heard myself saying to a freckle-faced young man who puffed uncomfortably on his fat roll of tobacco.

The first cigar smoker gestured for me to bend over as if he were about to share some important confidence. “Now, Larry, here’s what I want you to do. Go get us some of those peanuts and then give my guests and me a fresh ashtray. Can you manage that?”

April 19 (Sunday)

It was Easter Sunday, and the Easter-egg hunt began with dozens of small children scampering around the tulips and daffodils while well-dressed parents watched wistfully from the rear patio of the club. A giant Easter bunny gave out little baskets filled with jelly beans to parents and then hopped over to the bushes, where he hugged the children. As we peered out from the closed blinds in the grill, we saw women in mink, husbands in gray suits, children in Ralph Lauren and Laura Ashley. Hazel let out a sigh. “Aren’t they beautiful?” she said. For just a moment, I found myself agreeing.

As I raced around taking out orders of coffee and baskets of hot rolls, I got a chance to see groups of families. Fathers seemed to be uniformly taller than six feet. Most of them were wearing blue blazers, white shirts, and incredibly out-of-style silk ties—the kind with little blue whales or little green ducks floating downward. They were bespectacled and conspicuously clean-shaven.

The “ladies,” as the club prefers to call them, almost invariably had straight blonde hair. Whether or not they had brown roots and whether they were 25 or 48, ladies wore their hair blonde, straight, and off the face. No dangling earrings, five-carat diamonds, or designer handbags. Black velvet or pastel headbands were de rigueur.

There were also groups of high-school kids who wore torn jeans, sneakers or unlaced L. L. Bean shoes, and sweatshirts that said things like HOTCHKISS LACROSSE or ANDOVER CREW. At one table, two boys sat talking to two girls.

“No way, J.C.,” one of the girls cried in disbelief while playing with the straw in her diet Coke.

The strawberry-blonde girl next to her flashed her unpainted nails in the air. “Way. She said that if she didn’t get her grades up by this spring, they were going to take her out altogether.”

“And where would they send her?” one of the guys asked.

The strawberry blonde’s grin disappeared as she leaned in close. “Public school.”

The group, in hysterics, shook the table. The guys stomped their feet.

“Oh, my God, J.C., oh, J.C., J.C.,” the diet-Coke girl cried.

Sitting in a tableless corner of the room, beneath the TV, was a young, dark-skinned black woman dressed in a white uniform and a thick wool coat. On her lap was a baby with silky white-blond hair. The woman sat patiently, shifting the baby in her lap while glancing over to where the baby’s family ate, two tables away.

I ran to the kitchen, brought back a glass of tea, and offered it to her. The woman looked up at me, shook her head, and then turned back to the gurgling infant.

April 21 (Tuesday)

While Hector and I stood inside a deep walk-in freezer, we scooped balls of butter into separate butter dishes and talked about our plans. “Will you go finish school sometime?” he asked as I dug deep into a vat of frozen butter.

“Maybe. In a couple years, when I save more money, but I’m not sure.”

I felt lousy about having to lie.

Just as we were all leaving for the day, Mr. Ryan came down to hand out the new policies for those who were going to live in the Monkey House. Since it had recently been renovated, the club was requiring all new residents to sign the form. The policy included a rule that forbade employees to have overnight guests. Rule 14 stated that the club management had the right to enter an employee’s locked bedroom at any time, without permission and without giving notice.

As I was making rounds with my coffeepots, I overheard a raspy-voiced woman talking to a mother and daughter who were thumbing through a catalogue of infants’ clothing.

“The problem with au pairs is that they’re usually only in the country for a year.”

The mother and daughter nodded in agreement.

“But getting one that is a citizen has its own problems. For example, if you ever have to choose between a Negro and one of these Spanish people, always go for the Negro.”

One of the women frowned, confused. “Really?”

“Yes,” the raspy-voiced woman responded with cold logic. “Even though you can’t trust either one, at least Negroes speak English and can follow your directions.”

Before I could refill the final cup, the raspy-voiced woman looked up at me and smiled. “Oh, thanks for the refill, Larry.”

April 22 (Wednesday)

This is our country, and don’t you forget it. They came here and have to live by our rules!” Hazel pounded her fist into the palm of her pale white hand.

I had made the mistake of telling her I had learned a few Spanish phrases to help me communicate better with some of my co-workers. She wasn’t impressed.

“I’ll be damned if I’m going to learn or speak one word of Spanish. And I’d suggest you do the same,” she said. She took a long drag on her cigarette while I loaded the empty shelves with clean glasses.

Today, the TV was tuned to testimony and closing arguments from the Rodney King police-beating trial in California.

“I am so sick of seeing that awful videotape,” one woman said to friends at her table. “It shouldn’t be on TV.”

At around two, Lois, the club’s official secretary, asked me to help her send out a mailing to 600 members after my shift.

She took me up to her office on the main floor and introduced me to the two women who sat with her.

“Larry, this is Marge, whom you’ll talk with in three months, because she’s in charge of employee benefits.”

I smiled at the brunette.

“And Larry, this is Sandy, whom you’ll talk with after you become a member at the club, because she’s in charge of members’ accounts.”

Both Sandy and I looked up at Lois with shocked expressions.

Lois winked, and at the same moment, the three jovial women burst out laughing.

Lois sat me down at a table in the middle of the club’s cavernous ballroom and had me stamp ANNUAL MEMBER GUEST on the bottom of small postcards and stuff them into envelopes.

As I sat in the empty ballroom, I looked around at the mirrors and the silver-and-crystal chandeliers that dripped from the high ceiling. I thought about all the beautiful weddings and debutante balls that must have taken place in that room. I could imagine members asking themselves, “Why would anybody who is not like us want to join a club where they’re not wanted?”

I stuffed my last envelope, forgot to clock out, and drove back to the Merritt Parkway and into New York.

April 23 (Thursday)

“Wow, that’s great,” I said to Mr. Ryan as he posted a memo entitled “Employee Relations Policy Statement: Employee Golf Privileges.”

After quickly reading the memo, I realized this “policy” was a crock. The memo opened optimistically: “The club provides golf privileges for staff… . Current employees will be allowed golf privileges as outlined below.” Unfortunately, the only employees that the memo listed “below” were department heads, golf-management personnel, teaching assistants, the general manager, and “key staff that appear on the club’s organizational chart.”

At the end of the day, Mr. Ryan handed me my first paycheck. The backbreaking work finally seemed worthwhile. When I opened the envelope and saw what I’d earned—$174.04 for five days—I laughed out loud.

Back in the security of a bathroom stall, where I had periodically been taking notes since my arrival, I studied the check and thought about how many hours—and how hard—I’d worked for so little money. It was less than one tenth of what I’d make in the same time at my law firm. I went upstairs and asked Mr. Ryan about my paycheck.

“Well, we decided to give you $7 an hour,” he said in a tone overflowing with generosity. I had never actually been told my hourly rate. “But if the check looks especially big, that’s because you got some extra pay in there for all of your terrific work on Good Friday. And by the way, Larry, don’t tell the others what you’re getting, because we’re giving you a special deal and it’s really nobody else’s business.”

I nodded and thanked him for his largess. I stuffed some more envelopes, emptied out my locker, and left.

The next morning, I was scheduled to work a double shift. Instead, I called and explained that I had a family emergency and would have to quit immediately. Mr. Ryan was very sympathetic and said I could return when things settled down. I told him, “No, thanks,” but asked that he send my last paycheck to my home. I put my uniform and the key to my locker in a brown padded envelope, and I mailed it all to Mr. Ryan.

Somehow it took two months of phone calls for me to get my final paycheck ($123.74, after taxes and a $30 deduction).

I’m back at my law firm now, dressed in one of my dark-gray Paul Stuart suits, sitting in a handsome office 30 floors above midtown. It’s a long way from the Monkey House, but we have a long way to go.

All names of club members and personnel have been changed.