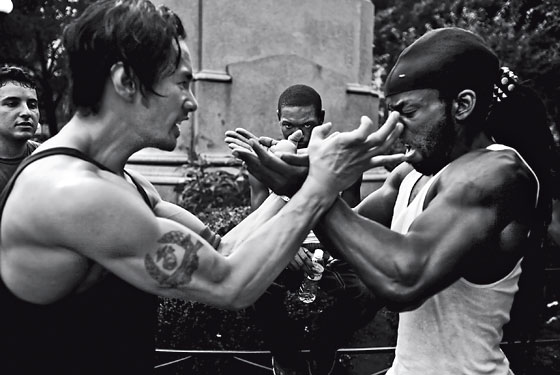

It’s a summer Friday night in Union Square. A short-haired preacher shouts about the perils of using the Lord’s name in vain. A high-on-something teenager listens for a moment, then flips off the evangelist with both middle fingers. The kids standing around them laugh, but only for a second. There’s a commotion by the subway kiosk at the southeastern corner of the park. It appears to be a fight. Two young men are locked together, their arms on each other’s shoulders, muscles and tendons bulging. The man on the left is a twentyish white guy, about six foot two and maybe 220 pounds, with bushy brown hair. He wears camouflage shorts and a T-shirt that reads I’M THE GUY YOU SHOULDN’T GO HOME WITH BUT WILL, SO WHY NOT JUST GO HOME WITH ME NOW? He could be a surf punk, except that he’s too big for that. The other man—a slightly darker-skinned guy, maybe a little younger—is massive, too, but he’s got a smooth, red-cheeked face and a layer of baby fat that make him look vulnerable, if not a little scared.

The two men wrestle some more, then separate and start throwing punches. Surfer Guy throws a hard right that lands on the other man’s kidney with a sickening thwack. A crowd has gathered, but no one tries to stop the fighting. Instead, people snap pictures with camera phones. The older man hoists the younger one over his shoulder. There’s a millisecond’s midair pause, then—thump!—both men crash to the concrete. The crowd lets out a cartoonish “Ooh!”

A friend of the younger man starts screaming. “Louyi, roll over him! Roll over him, and put your fingers in his eyes.”

Louyi does as he is told. He wriggles off the ground, grabs hold of the other man’s T-shirt, and spins on top. Surfer Guy gasps for air and whimpers.

“Finish him,” someone shouts.

Several hundred people are now watching; they’ve formed a circle. Across 14th Street, shoppers fill the windows of the Whole Foods and Filene’s Basement stores, turning them into luxury boxes. Louyi doesn’t stick his fingers in the other man’s eyes. He merely presses his fists into them until Surfer Guy surrenders.

Louyi stands up, flashes a Li’l Jack Horner smile, and pumps his fist.

The crowd is silent, slack-jawed. Midtown office drones, girls carrying Forever 21 bags, German tourists—no one knows quite what to say.

Now a black man with short dreads walks toward the fighters. His chest is bursting out of a tight white tank top, and a dog collar hangs around his neck. He squints at the onlookers with a wild stare. Everyone gives him a wide berth. But then he breaks into a childish grin. He’s just fucking with people.

“That’s Legend,” a bystander whispers to a man standing next to him.

Legend gives Louyi a benedictory soul shake. Louyi beams.

Then Legend turns toward the crowd and seeks out another black guy who was filming the first fight. He’s wearing long jean shorts and a baseball cap with spikes on it.

“Science, you ready?”

Legend and Science go at it themselves for fifteen minutes, exchanging a series of kicks and punches and an assortment of other cinematic martial-arts moves. When they’re done, they bow and embrace.

The crowd claps. Legend speaks. “We’re the Union Square Spartans,” he says. “Who wants to fight next?”

Ever since Chuck Palahniuk published Fight Club in 1996, rumors have circulated about illegal underground fights held in the basements and boiler rooms of New York and elsewhere, modeled after those in the book and, several years later, the Brad Pitt film of the same name. The most quoted line from the movie was “The first rule of fight club is, you don’t talk about fight club.” That’s not the Spartans. They fight in public, outdoors, at one of the city’s busiest crossroads. They want to be seen. Where Palahniuk’s characters were mostly middle-class white guys, the Spartans are mostly black city kids, some of them homeless. They put their fights on YouTube. They know many among their growing body of fans take voyeuristic pleasure in watching them fight, and they’re somehow looking to make money off the whole business, but they are warriors without a business plan.

Legend is leaning against the brass railing that surrounds the George Washington statue. The neon glow from the Coffee Shop lights up the night behind him. It’s been an hour since he and Science fought. He’s shirtless and drenched in sweat. He has his arm around a pixieish white girl whom he calls Strawberry, except when he calls her Snowflake.

Buzzing around Legend is a tiny tough-talking kid throwing kicks in the air. He looks 12, but he’s really 16. Everyone calls him Chucky. The high-on-something preacher-hater reappears. He introduces himself as Shadow. He’s a Spartan, too. The rest of the happy few go by names like C.J., Two-King, and Joker.

Still, this is clearly Legend’s show. He’s attended by two faithful aides-de-camp: Science and a shy, gangly kid named Spider. A cheap cigar is hollowed out and filled with pot. I ask Legend about the Spartans. “There’s always been a caste system,” he says. “There’s always been the clerics, there’s always been the scholars, and there’s always been the warriors.” Legend talks in flowery, cryptic terms. “Just because you say the color gray doesn’t exist doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist,” he says. “The same thing with the warriors. We’re the warriors of now.” The Spartans are run by the Triangle. “The Triangle is our leadership council,” Legend says. “Me, Spider, and Science are the Triangle.”

A few days later, I find Legend, Spider, and Science ducking out of the rain in what they call their Bat Cave, a small overhang adjacent to the Virgin Megastore across from Union Square. Legend grabs my arm. “C’mon, we’re going on a mission.” I trail the Triangle and Strawberry into the rain. The mission turns out to be just a quest for slightly better shelter, which we find on a 15th Street construction site across from the Park Bar. A joint is passed around, and the three men talk about how they met.

Legend says he grew up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, near the Gates housing projects. “They called it the ‘Death Gates’ because someone was getting murdered there every week,” he says. Legend’s father was a Navy SEAL. “When I was 3 or 4, he started tossing a heavy bag at me, and I had to dodge it. It was all soft, but it would knock me on my ass, so I had to learn how to move.” Legend claims his father taught him martial-arts moves and secret holds he’d learned in the Navy. As he got older, he says, his father would be gone for long stretches at a time. “You know, on secret missions or supervising projects.”

“The Spartans are the fighters,” says Science, “but Union Square is all of Sparta. It was like we had the idea in our heads, and the movie ‘300’ came out, and we were like, ‘Aha.’ ”

Legend is clever and could be inventing his myth as he goes along. Still, some of his story is demonstrably true. He says he joined the Crips at 12. “My whole neighborhood is Bloods, but I always do the opposite.” He shows me several scars on his arm, then places my hand on a small indentation on his forehead. “I went over to a friend’s house in Bed-Stuy one day to smoke weed and play video games,” he says. “I just opened the door, and two guys started beating me with a baseball bat with a nail on it. My friend just watched.” He says the attack was random.

Legend’s mother eventually gave up on raising him, he says. He was farmed out to group homes in the Bronx, where he attended Adlai E. Stevenson High School. “Nobody bothered me at Stevo, because I’d already grown into the face I have,” he says. Although Legend looks black, he insists he’s more than half Native American. “By the time I was 17, I realized I had the Native American stone face. It can be really intimidating.” He spent most of his high-school years cutting class and gang-banging, but talks dreamily about how much he loved learning about war and history, particularly warriors like Geronimo.

While he was working as a bouncer around town, he started visiting underground fight clubs, mostly in Chinatown. Legend says he would find himself in a basement surrounded by screaming drunks. Another fighter would enter the circle, and they would battle with no rules until one of them was unconscious. Legend says he’d leave the room with concussions, broken ribs, and maybe a couple of hundred dollars. “Those places, they only stop the fight if the crowd stops cheering or begins leaving,” he says. “They don’t really care if you live or die.”

Legend, who is 23 now, says he has an apartment in Sheepshead Bay, but he spends most of his time in Union Square and often sleeps there. He drinks some, but his self-medication of choice is pot. “Weed is what keeps me right,” he says. “The only time I get nervous and agitated is when I can’t get any weed.”

In fact, Legend has a volatile personality. At any given moment, he can toggle between wise and childlike, open and guarded, loving and menacing. Most of Legend’s friends are mostly girls, he says. “Guys are weird. I don’t get along with them. They seem threatened by me. I’ll be like, ‘Hey, I’m just chilling, doing my thing, you just do your thing.’ But they always seem to want to put out your light just because your light is stronger.”

While Legend is talking, Science is drawing medieval fighters in a sketchbook. He says he grew up on the Lower East Side and has twin sisters who just graduated from college. “My dad was just a sperm donor, I didn’t get along with my mom, and I was out of the house when I was 12,” he says.

Science lived with family and friends through his teens, but he’s been mostly homeless for the past decade. “I’ve always been a ronin,” he says, referring to the Japanese term for a rootless warrior.

Like Legend, Science once fought in underground fight-club bouts to make some cash. But he’s less of a tough than Legend. “It was down in Chinatown in a garage. We were surrounded by cars with their lights on, and I was really nervous. Then the fighter gets in the middle with me and it’s a woman. And I was like, Should I punch back? By the time I did, another guy jumped in the ring and I got the shit beat out of me.”

Spider, who’s 23, is painfully thin, and still has a trace of adolescent acne. He is the quietest member of the Triangle. He was born in Panama and moved to New York when he was 6. He first lived in Flatbush and then Crown Heights. Like Legend and Science, he never really knew his father.

Spider went to Louis D. Brandeis High School on the Upper West Side but got kicked out in the tenth grade after getting into a fight with another student. Spider left home at 16 and spent the next two years living in Union Square during the day and on the Q train at night.

In 2002, Spider headed to the Port Authority and settled in Norfolk, Virginia, before coming home. Now he’s the only one of the three to have a job, working at a nearby Papaya King. “I’m the most cautious of the three of us,” Spider tells me.

It’s raining harder now. Spider shivers. Strawberry and Legend do a little stoned dance to stay warm. Science tucks his sketchpad under his sweatshirt to keep it dry. I suggest we get a pizza at a place on Sixth Avenue. “No, a cheese will cost you like sixteen there,” says Spider. “There’s a place on St. Marks where you get one for eight.”

As we walk down Broadway, Legend shares what he sees as the Spartans’ purpose. “I want it to be competitive, but like a family,” he says, holding Strawberry’s hand. “It makes you tough, but it shows you love. I didn’t have that as a kid.”

The Spartans’ creation myth begins at the Pyramid Club, on the Lower East Side. Science worked for the club, but different floors would be rented out to independent promoters who provided their own security. One night in the winter of 2005, Science was summoned to handle a situation where a group of drunken men were harassing a woman. By the time he arrived, another bouncer was already on the scene.

“This guy went to the pressure point under the armpit on the first guy,” says Science with awe. “Then he hit his palm under the windpipe of another guy. I was like, This guy has moves.” Science and Legend escorted the offending patrons out of the club. “Once we got outside, we started talking about how we had both done martial arts as kids. Then we started sparring out in front of the club, right then.”

Science invited Legend to hang out with him in Union Square. The timing was excellent. Legend had been living with a girl in Brooklyn, but it had ended badly, with Legend’s girlfriend chucking a jar of applesauce at him, slicing open his arm. He had nowhere else to go.

At first Science and Legend had a different idea about how to make money off their fighting skills. They would spend hours talking about how cool it would be to choreograph fight scenes for the movies, then they’d work out sequences and perform them for their Union Square friends. Legend and Science taught some of their friends their moves. Spider was one of them, and the three men became close. Science nicknamed the trio the Triangle after something he read in a book about ancient warriors. “All warriors are equal,” says Science. “But there’s a triangle of warriors that leads the phalanx into battle. That’s us.”

Legend says he’s been known by that name since he can remember. Science’s real middle name is “Scientific” because his mom hoped he would become a scientist. Spider got his nickname because he loves Spider-Man comics. I ask Legend if he and the others will tell me their real names. No, Legend says. “When a warrior is born, he has a milk name, you know, from when all you drank was milk. But when he grows up, he gets a warrior name that is more who he is. This is who I am.”

“Words are power,” adds Science. “If I know your first and last name, I know who you are. I have access. I have more control over you.” He motions at Spider and Legend. “They know my government name if it’s an emergency. But I trust them. We’ve jumped out of windows. We’ve fought together. They’ve earned it.”

The Spartans’ fights started out informally. “We’d just spar with each other without any rules,” says Science. But over time, the Triangle started pairing up friends of similar ability, and rules were drawn up. The fights would follow the basic guidelines of mixed-martial-arts fighting, the hybrid combination of boxing, wrestling, and martial-arts moves that’s become popular in recent years on cable TV. The fights would consist of three rounds of approximately five minutes each (fighters could surrender earlier by tapping the concrete). There would be two critical deviations from mixed-martial-arts rules: No blows to the head were allowed, and fights would be about improving one’s skills, not about hurting or humiliating one’s opponent. The first rule was practical, the second philosophical.

“We figured out, if you were not punching to the head, it was legal to do this publicly and say we were just training,” says Science. “And we wanted this to be like a family. You get humiliated by the world every day. That’s not what we’re about.”

In the spring of 2007, the movie 300 opened at the Union Square Regal Cinema. The film retells the legend of the 300 Spartans who died fighting the Persian horde at Thermopylae. Spider, Science, and Legend watched it repeatedly, transfixed. “I came up with the name the Union Square Spartans,” says Science. “The Spartans are the fighters, but Union Square is all of Sparta. It was like we already had the idea in our heads, and the movie came out, and we were like, ‘Aha.’ ”

“When a warrior is born, he has a milk name, you know, from when all you drank was milk,” Legend says. “When he grows up, he gets a warrior name.”

Not long after the movie premiered, the Triangle watched as medieval combatants wielding spears and shields invaded Union Square. Turns out they were members of the Darkon Wargaming Club, a role-playing society that reenacts fantasy battle scenes. “They put a lifeguard chair up, and I ran up there,” says Science. “I shouted, ‘Spartans, what is your occupation?’ And everyone shouted back, ‘War!’ They let us fight them with their plastic swords, and of course we won. That made us think we could build a world, too.”

The Astor Place cube is just ahead. Legend, Science, and Spider run through traffic and start pushing on it. Legend and Science begin chanting, “Union Square Spartans! Union Square Spartans! Union Square Spartans!” At the moment, they look less like warriors than a pack of bratty junior-high kids. Then Legend shares a fantasy he has for the Spartans: “I’d love it to be the Union Square Spartans take on the Ukraine,” says Legend, his dark-brown eyes lighting up. “The Union Square Spartans take on Cuba.” He seems to believe that there would somehow be money involved. “Everyone in the club would make the same amount,” he says. “I wouldn’t get an extra penny just because I’m the leader.”

We arrive at 2 Bros Pizza on St. Marks Place a few minutes later. Two large pies are devoured in minutes. It’s not clear when the Triangle’s last real meal was. Legend shakes hands with the manager.

“Soon, we’re going to be famous,” proclaims Legend. “You can put a sign up saying PIZZA CHOICE OF THE UNION SQUARE SPARTANS.”

The man smiles and makes another pizza.

Although the triangle members were enjoying their newfound camaraderie and purpose, they were still flat broke. One day in April, Science showed up with a video camera; he had the idea of filming some of the group’s fights. Maybe, he reasoned, if people saw them, they would come down to Union Square and the Triangle could charge them ten bucks a lesson.

Legend and Spider thought this was an excellent idea. In April, Science created the Union Square Spartans MySpace page. He then placed some of the fights he filmed on YouTube. Alas, the Triangle’s original goal of attracting fighters willing to pay for lessons was a failure; Science says no one has paid.

But there was a publicity boomlet. The blog And I Am Not Lying wrote about the fights in May, other blogs followed, and crowds began to show up at Spartan fights. The Triangle enjoyed the spotlight in a charmingly time-delayed way. A printout of the And I Am Not Lying item arrived like a nineteenth-century transatlantic letter, three weeks after the fact. Legend carried it around for a while like a holy relic. There was one line he loved to quote: He kept asking the other Spartans, “Am I really ‘petite and diamond hard?’ ”

By June, up to 300 people were watching Spartan fights on a Friday night. Baristas at a nearby Starbucks, who had banned them for rowdiness, now welcomed them to use their bathroom. There was even a rumor that ESPN had contacted the Spartans about filming their bouts and airing them as the ultimate-fighting equivalent of Harlem’s Rucker League.

Still, Spider insists the group doesn’t fight for the attention. “We fight in public because we have nowhere else to fight,” he says. “And we fight because you get that rush of ‘Oh, shit, did you just see that move?’ That’s the same rush, whether there’s three or 300 people watching.” Besides, he says, “if the economy keeps going bad, we could be in a civil war in two years. We’re gonna need to know how to defend ourselves.”

It’s a hot weeknight. Legend and Science lead a wiry 19-year-old called Munkey and a newcomer called Mexican into the ring. Munkey expertly uses his lower center of gravity to his advantage, and within a minute, his opponent topples. Legend is impressed: “Munkey, way to use the leverage.”

Then two cops shoulder their way through the crowd. The police have more or less ignored the Spartans for more than a year now, but the crowds the group has started attracting seem to have engendered a change in policy. One of the cops has a crew cut, and he approaches Legend and Science. “We’re getting calls saying there’s fights going on in Union Square. You can’t do this here.”

Science tries to reason with him. “We’ve been doing this for a year. It’s just sparring. There are no blows to the face. Everybody does t’ai chi here. It’s the same thing.”

“I thought we were going to have a roundtable meeting about this,” Flow says. “This isn’t a democracy,” says Legend. “So why don’t you shut up, and let us handle it?”

“Look, we can argue all night,” says the cop. “Next time we come back, we’re arresting people.”

Science tells him that they’ve applied for a permit. The cop laughs. “You think you’re going to get a permit for fighting in Union Square? That’s never gonna happen.” The cop stares down Science and laughs again. “You know, if you were doing this as a fund-raiser for the troops, you could probably get a permit.”

The cop and his partner walk away. The crowd disperses. The Spartans regroup under the George Washington statue. Everyone looks depressed. Legend glares into the distance.

After a minute or so, a Spartan named Flow speaks up. He’s a medium-built, studious-looking black guy, in his mid-twenties, with a Star of David necklace around his neck.

“I told you putting this on YouTube was a mistake,” Flow says. “We’re moving too fast. This wasn’t supposed to be about us getting famous.”

In the brief history of the Spartans, there has been relatively little dissension. But now, Legend, Science, and Spider surround Flow. Legend speaks first.

“You don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.” He looks at his two lieutenants for confirmation. “What do I keep saying? It doesn’t matter what the pawns do. We know the king.”

Flow looks confused. “What the fuck does that mean?”

“We know a guy who knows Ray Kelly,” Legend says. “We’ll be fine. We just ignore the pawns.”

“I thought we were going to have a roundtable meeting about this,” Flow says. “What happened to that?”

“This isn’t a democracy,” says Legend. “You’re not part of the Triangle. I tell everyone, ‘Do the things you love, and we’ll all get rich.’ We’re splitting everything with equal shares. I am not getting one dime more than anyone else. So why don’t you just shut up and let us handle it?”

“This isn’t what I wanted out of this,” says Flow.

Legend balls his fists. He has to be held back by Spider and Science. “Where do you think I grew up? It was Brooklyn, and it wasn’t Flatbush, I’ll tell you. It was Bed-Stuy.” Legend points at the indentation on his forehead. “Look, put your hand here,” he says to Flow. He tells him the story about the baseball bat. “No fucking reason,” he says. “That’s what life is about.”

Flow shifts his feet. Legend gets back in his face. “You’re either with us or I’ll cut you off. I’ll cut off your legs and leave you in the woods.”

Flow drifts off. Then Legend repeats the same line to no one in particular: “I am an antisocial sociopath who hates base behavior. I am an antisocial sociopath who hates base behavior.”

At the moment, you believe him.

A few days later, I come back to Union Square at dusk. Legend is standing in the same place where he and Flow had been arguing. But tonight, Legend is feeding a bottle to a cooing baby boy in Oshkosh B’Gosh overalls. The baby’s name is Xavier Jr.; he’s the son of two Union Square regulars. Strawberry handed him to Legend a few minutes before, but now he doesn’t know where the parents went.

“Let me show you something,” says Legend. “Babies are so cool.” He takes the bottle away for a second and touches Xavier’s dimpled chin. Xavier’s mouth magically pops open. “When they feel pressure there, they think it’s the bottle or the nipple,” Legend says as he reinserts the bottle.

We watch the baby feed for a moment. “This makes me think of my twins, Romeo and Caesar.” This catches me by surprise; Legend hadn’t mentioned he had children before.

“They’re 6. They live in Sheepshead Bay, but I don’t see them that much. Soon, I can start training them, if their mom lets me.”

He tells me the Spartans are in a state of flux. The NYPD precinct captain came out this week and reiterated that any more sparring would result in arrests. “We’ll move to Tompkins Square or somewhere else,” insists Legend. “Or get a permit.” But Union Square will always be base camp, he maintains. “We’re always going to be here. We’re always going to be the Union Square Spartans.”

I ask him about the supposed interest of ESPN in making some sort of deal with the Spartans. Legend ducks the question, but I find out later from Science that that was just a freelance promoter/huckster passing through the square and talking big. They never heard from him again. Still, Legend insists, other things are happening. He says a Staten Island fight club called the Greens saw video of the Spartans and have invited them out to Staten Island for a battle. “I watched some of those dudes fight,” Legend says. “They suck. We can take them all. This is just the start. This time next year, we’re going to have two gyms. One for training, one for us just to hang out.”

It’s not at all clear where they’d get the money, but that’s only one of the Spartans’ problems. In a few weeks, Legend will get picked up by the police for passing out on a Union Square bench and be hauled down to Centre Street on vagrancy charges. In the course of trying to find him again, I will find out that his real name is Glen Williams.

Tonight, Legend laughs when Xavier spits up on him and then hands the baby off to Strawberry. He looks out at Union Square. It’s the same scene as most nights. A man walks around with a sign that reads FREE HUGS, a New Orleans Dixieland band plays out of tune, and cabbies ride their horns. Legend gives a little wince.

“I love it here, but man, if we could get out, that would be great, too.”