On a recent Wednesday, Michelle Obama looms over a crowd of about 200 in Pontiac, Michigan, a Detroit suburb after which the car was named. In her chic outfit—sleeveless navy dress, delicate gold jewelry, peep-toe patent-leather shoes—she verges on six feet, and her firm-hold Jackie O. coiffure adds a few inches to the top. The dress fits snugly, with a bit of blue-and-orange-beaded flair sewn near her chest bone, sparkling like a costume necklace from a flea market. These days, Michelle campaigns about twice a week—she’ll appear at one public event per city, then a fund-raiser, and hop back to Chicago to see her kids before they fall asleep. Fund-raisers are important, since her husband is not taking public financing for his campaign, but they are private events, which allows Michelle to engage in what appears to be a lot of campaign stops but only adds up to one or two solitary hours per week in front of cameras.

The exercise during these hours is to say nothing. In front of this crowd, Michelle has morphed into a repository of emotion, an Oprah-esque icon of inspirational womanhood who promises the same feel-good message with an even softer delivery. Her voice is pitched in the range of Tila Tequila. Her eyes are grottoes of compassion. The singular blemish on her otherwise gorgeous face—the eyebrows, in person, are not quite as angular as one expects—is her brow, which has worked into a groove too deep to be eliminated by a slick of foundation.

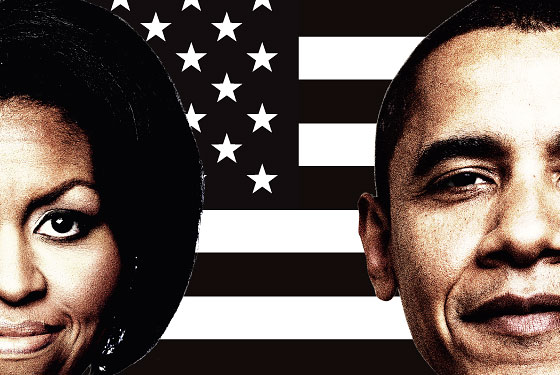

Michelle’s presence could not be more powerful, but she has done her best to obscure her boldness since mid-June, when the campaign began to roll out a new image for her with an appearance on The View. “All this talk about softening my image just really cracks me up,” she protests later, via e-mail. “I’m the same woman I’ve always been.” Early in the campaign, she came off as sassy and sarcastic, teasing Obama about his morning breath and forcing him to quit smoking before she gave him permission to run for president. She assessed our divided country candidly, calling it “downright mean” and full of people “guided by fear.” Now she has another purpose: to let people cry. A square blue box of tissues has been placed onstage, next to an unattractive plant.

“She’s going to be good,” says one woman, in the audience. “She’ll have us all crying!”

And cry they do, sharing their stories of health-care crises, job losses, subprime-mortgage nightmares, about daughters dumping their out-of-wedlock babies at their door and toddlers who are forced to split a hamburger because there’s no money for two. It’s group catharsis with Michelle as Mary in the Pietà, with the groove in her forehead becoming increasingly pronounced. The purgation goes on for an hour, with only the most minor of laugh lines: “I wasn’t stimulated by President Bush’s stimulation,” says one woman, from the balcony. “Will President Obama do something similar to a stimulus process?” Michelle laughs, then says, coyly, “Yes, Barack is talking about doing something for short-term stimulation.”

Things are starting, blessedly, to come to a conclusion when she finally lets the veil slip, revealing a bit of her old self. “I don’t want to sound like a broken record,” says Michelle, dodging a question about her husband’s policies to help small-business owners. “But I’ve decided to stay away from getting Barack’s policies wrong, because it’ll be on the front page.” She puts her hand on her hip. “Then he’ll be like, ‘You said what?’ ” She nearly snaps in the air. “ ‘Yeah,’ ” she says, puffing out her chest, “ ‘I said you were gonna do this and that!’ ”

A prospective First Lady carries a heavy symbolic burden, but the notions that have coalesced to tongue-tie Michelle Obama are particularly dense. She’s a type we’ve rarely seen in the public eye, a well-educated woman who is a dedicated mother, successful in her career, and happens to be black. This has created confusion for some people, who seem desperate to find a negative quality in her: She’s too big, too masculine, too much like a drag queen. While Obama may be able to play with urban tropes, like dusting off his jacket à la Jay-Z or speaking in a black patois when the time calls for it, Michelle has been increasingly forced to curtail her personality during the campaign, lest she attract rumors of uttering a verboten, anachronistic word like “whitey” or find herself labeled a “baby mama.” As much as any political campaign is an extended meditation on authenticity, the question of just how black the Obamas are has become particularly loaded. Michelle must project herself as black to one community, but she also must act white to another, whatever either adjective means nowadays.

The lunatic-fringe memes of terrorist fist bumps and jelabas can be reasoned away. But race in America is a matter of deep family neurosis. A real conversation about it, such as the one invited by Obama in his speech after the controversy over the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, would be full of missed communication and mutual incomprehension—not the best discussion to have during election season. Even though pretty much everyone—even Al Sharpton—would agree that grievance politics has run its course, that doesn’t mean that the grievances are gone. In general, most white people think that America’s problem with race has been solved, and any suggestion that it hasn’t tends to ignite an unstable keg of guilt and anger—the kinds of feelings Oprah would tell us to confront head-on, though it’s easier to live in denial.

The Obamas, who embody a drama with race as its central theme, know the score, racially speaking, even if they can’t say that they do. By virtue of Obama’s calm, collected nature—most likely learned during his childhood in Hawaii, where losing one’s temper is taboo—he has been able to completely defang the stereotype of the angry black male (with a helpful foil in John McCain, who seems perpetually on the verge of smoke pouring out of his ears). There’s only one moment where Obama got a little upset, on Good Morning America, reprimanding conservatives for beating up on Michelle—“Lay off my wife,” he said, then flashed his zillion-watt grin. In any case, he earned extra points for that, because who doesn’t love a man who stands up for his woman? For the first time in years, this presidential couple seems not only to be an egalitarian unit, but like they’re really in love with each other (the fist bump, whether it was spontaneous or not, had a lot of eye contact associated with it).

The description of the Obamas’ life together displays no evidence of their connections to black culture, especially now that it’s not prudent for them to join a new church before the election. They take pains to make sure their lifestyle is as boring as possible. They’ve easily resolved knotty personal issues: Michelle’s 71-year-old mom, Marian Robinson, takes care of the girls, so they don’t have to hire a nanny, which would make them look a little too buppie. (The girls still have the packed schedule of upwardly mobile kids: soccer, dance, drama, gymnastics, tap, tennis, piano. Obama doesn’t like them watching TV.) “When we’re all together in Chicago, we like to play games like charades,” Michelle tells us. “We also love a busy house, which means potluck dinners with our close friends and family as often as we can.” We have little idea of the racial makeup of such potlucks. “Some of Michelle’s closest friends are white, and her sister-in-law Maya is white,” says Angela Acree, a friend of Michelle’s. “She says reporters always get these shocks when they call up her white friends. ‘Yeah, I’m a white girl!’ her friends will say. ‘Now, what’d you want to know?’ ”

And what does the white world know about black people like the Obamas, really? “The black middle class is the most invisible, unknown group in the country,” says Gayle Pemberton, a professor of African-American studies at Wesleyan University. “There are millions and millions of people in it, and yet we know nothing about them.” One would think that the Obamas enjoy being called the black Kennedys, but maybe they don’t. “This Camelot myth has formed around Barack and Michelle, but they come from almost the opposite place in the world from the Kennedys,” says Obama’s friend Kenneth Mack, a law professor at Harvard University. “If you saw Barack on a yacht, that would be pretty unseemly. He’s the guy from the basketball court who used to go around in jeans and a leather jacket. In law school, he was really uncomfortable with the markers of elitism, like even dressing in a suit.” It’s a sitcom, this miscommunication between black and white people: In fact, a manager in Hollywood told me that he’s getting calls from producers searching for TV writers to work on All in the Family–style shows for next year—they know the country will be hungry for this type of comedy if Obama is elected.

While Michelle hasn’t made many interesting statements in public—it’s a very small canon of comments, over the course of almost two years of campaigning—they’ve taken on enormous meaning. She’s not quite as smooth a political player as Barack: “Whenever Obama enters the room, there’s a sense of calm and satisfaction,” says a former campaign aide. “Michelle can get a little more tense. Before she goes on-camera for interviews, we’d have to give her a couple of minutes to compose herself. She’ll sit down, raise her hands over her head, and go, ‘Ugh, God!’ ” That’s a mask she’s wearing in public, most of the time, and we aren’t sure what is underneath. When she uttered her fateful words about how, for “the first time in my adult life, I’m really proud of my country,” she unleashed an explosion of emotion, because everyone who’s awake could read between the lines—she was angry about the treatment of black people in America. And anger will not do. Besides, what does she have to be angry about, with her Ivy education and Hyde Park mansion? Isn’t she herself an example of the fact that racism is over in America?

This guy is everything to everybody,” says a black man darting through crowds outside the campaign event in Pontiac, peddling a stack of Obama T-shirts for $10 each. “Love, my favorite color’s blue, and you’d look fine in it,” he hollers into a Cadillac, driven by a white woman with a ton of kids in the back. He keeps up a monologue, about his younger days with Stokely Carmichael, and the way that Obama has inspired him to get back in touch with a kid he fathered years ago. He talks into the window of the car: “See, Barack is the son of an African immigrant, which I like since I adopted me a country years back, but he’s a Harvard grad, with a white mom and white grandma.” The lady reaches onto the dash for her purse, and forks over the cash. “Black as this guy is,” he tells her, “he’s whiter than you!’ ”

One of Obama’s central arguments, and one he embodies, is that racial categories are obsolete. The inherent promise is that he’ll transcend identity politics, moving us into a post-p.c. era where one’s origins and orientations do not stand in for your beliefs—a time when even decolonized, self-actualized, bisexual Latinas won’t feel the need to constantly define themselves. But it’s not hard to discern race in the patterns of the Obama campaign. In July, about a third of Obama’s public events were speeches given in front of primarily minority or black audiences, with the exception of his overseas extravaganza. Yet nearly every night is taken up with fund-raisers, which primarily draw white donors. It’s a journey through class and race segregation in America, every day.

It’s much remarked upon that the rhetoric Obama has chosen for primarily black audiences—of discipline and personal responsibility—is edifying to different ears as well; his Father’s Day speech at a black church was a soft-sell Sister Souljah moment, announcing that the brothers are not going to get a pass just because he looks like them. But in person, at a primarily African-American town hall in Powder Springs, Georgia, he’s playful in these discussions, engaging in a kind of call-and-response between leader and flock. He lengthens his vowels, loses a bit of the midwestern accent, and if he doesn’t exactly break out into laughter, he grins easily. Obama is particularly comfortable in front of black audiences, who inspire him to be passionate and energetic. Watching him, I wondered if in this context he would use the N-word, if only to make a point. (Although Michelle would give him hell for it: “I don’t tolerate the use of that or any other disrespectful or denigrating term,” she tells me.)

Obama paces the stage. “Parents—you gotta turn off the television set and put away the video games,” he says, lifting an arm. “You gotta have a curfew!”

“That’s right,” bellows the crowd.

“And go to your parent-teacher meetings, and help your kids with their homework!”

“Come on!”

“And if your kid gets in trouble at school, don’t blame it on the teacher. But at the same time, teachers got to behave!”

Afterward, the crowds mob him. One woman comes dashing out, holding her hand up. “I’m never going to wash my hand,” she yells. “I gotta get a plaster-of-Paris mold!”

Obama is almost a singularity in America, in that he understood his blackness—and its costs—intellectually before he felt it.

Here in Powder Springs, they know that Obama is one of them. But the unsettling part, the one that Jesse Jackson was trying to get to, is that Obama is also very much not like them. Up close, he has a lot of Harvard in him, too. He has a princely air, with a habit of keeping his chin positioned a little too high and sniffing the air repeatedly. He’s a waif, much thinner than one would expect, except for a pair of broad shoulders that pull at the ends of his gray suit jacket. On a rope line, Michelle is boisterous and playful—“You a real sister!” one woman tells her, holding her hand for too long—whereas Obama tends to zip through crowds, with no hand held for more than a couple seconds at a time (to be fair, his Secret Service detail is said to be large and twitchy, owing to concerns that harm may come to him because of the color of his skin). He’s got a great friend in his smile, but there’s nothing special about his eyes, and they are not looking for yours.

But black people realize that Obama is doing what every successful black man in America has to do: flip the script. “There’s a lot of people out there who want Obama to be all pro-black,” says Eric Dickerson, the former NFL running back, at Tao one evening for Michael Strahan’s golf charity event. “But we’re living in the United States, and this country is mainly white. You have to conform, you really do. I think he’s fine the way he is. He got both sides of the culture, like Tiger Woods. None of us can denounce one or the other—we have to have both. That’s just the society we live in.”

Obama is almost a singularity in America, in that he understood his blackness—and its costs—intellectually before he felt it. It was a choice, which he made open-eyed. Obama’s life growing up in Hawaii amongst haoles, Filipinos, and Japanese just wasn’t like a black man’s on the mainland. The African-American population of the state in the seventies was less than 2 percent, and the disenfranchised population in the islands were native Hawaiians. It was before the advent of MTV, so ghetto-speak wasn’t ubiquitous, and kids who liked to slum it with language played with pidgin. “Barack loves coming back to Hawaii because it is a gentle place, a place he can be himself,” says his half-sister, Maya Soetoro-Ng. “He had friends from all different backgrounds when he was growing up, and a lot of them were local. They’d cruise around in their beat-up beach buggies, going bodysurfing. Barack didn’t surf—his sense of balance wasn’t all that great.”

Not a single ancestor of Obama’s had blood from Hawaii, a place farther away from anywhere else than any other place on Earth (California is the nearest shore to Hawaii, at 2,600 miles away). His mom, Stanley Ann Dunham—given a boy’s name by her father because he’d hoped so much for one—was a free-spirited anthropology student at the University of Hawaii when she met Obama Senior, the first African student at the university. (As a black comedian put it, jarringly, at an Obama fund-raiser and comedy workshop I attended recently, “His mom screwed the darkest nigger she could find in 1969.”) The couple separated when he was 2, with his mother marrying an Indonesian, and his father eventually returning to Kenya to take more wives before dying broke and bitter.

From his mother, Obama received the message that blacks were the chosen people: “Every black man was Thurgood Marshall or Sidney Poitier; every black woman Fannie Lou Hamer or Lena Horne,” he has written. “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” He knew there was something wrong with this picture and started to resent her for her naïve romanticism, embarrassed by the way she cried when they went to see Black Orpheus. A pattern started to emerge: There was the white tennis pro who had told him not to touch the schedule of matches on a bulletin board because his “color might rub off,” or the assistant basketball coach who told him, after they lost a pickup game with some black men, that they shouldn’t have lost to a bunch of “niggers.” There was even his white grandmother, who refused to take the bus to work after a guy harassed her at the bus stop—not just any guy, but a black guy.

In Obama’s autobiography, Dreams From My Father, he puts a pivotal part of his racial awakening in high school, a largely white private school in Honolulu. There, he met a half-black and half-Japanese student who taught him that the slights he brushed off when he was younger were the product of institutional racism. But this student, Keith Kakugawa, has denied to the Chicago Tribune that he played such a role, claiming that “Barry’s biggest struggles then were missing his parents. His biggest struggles were his feelings of abandonment. The idea that his biggest struggle was race is bull.” Obama’s memories of attending parties on military bases with black soldiers, in an attempt to feel connected to his race, have also been called into question by other black students. (Kakugawa has had a hard time fitting into the world himself: He’s been convicted three times for drug offenses and as of a year ago was homeless on L.A.’s skid row, which could call his memory into question.)

By college, Obama was still not sure where he belonged. At Columbia, he dated a white girl for a long time. One night, after seeing a provocative play by a black writer in New York, she asked him why black people were so angry all the time. “We had a big fight,” he writes. “When we got back to the car she started crying. She couldn’t be black, she said. She would if she could, but she couldn’t. She could only be herself.” The gulf between them was too deep. They split up quickly.

While Obama struggled to incorporate blackness into his life, Michelle had to learn to integrate into the white world. She grew up in a strong black community on the South Side of Chicago, with a father who was a pump operator for the City of Chicago’s water department and who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at 30. It’s a story that embodies the American Dream, or a black version thereof. “Even though my father depended on the assistance of a cane and eventually a motorized cart, even though he was in pain, he was never late and never complained,” says Michelle. “He did it every single day so he could send me and my brother to some of the best schools in the country. His priority was to provide for his family and give his children the tools to succeed in life, and he did.” (The loss of Michelle’s father, in 1990, led her to pursue a life of public service: “It was a real awakening for me,” she says.)

Michelle’s father wanted her to succeed in elite society, so she left the neighborhood for Princeton University, a place where she felt more like an outsider than Obama ever could have. She hung out at the Third World Center, part of a tight-knit circle of friends who didn’t belong to eating clubs, and worked an after-school job every day, waking up at dawn to do her schoolwork. Her thesis, “Princeton-Educated Blacks and the Black Community,” sought to answer the question of whether black students like herself—in 1985, the year of her graduation, this was a small group—would choose to assimilate to the white professional world or decide to aid lower-income communities after graduation. The thesis speaks of an experience of alienation felt by many rising black Americans trying to make it in the white world, but to some eyes it may make her seem insufficiently grateful for the fruits of her success. “I sometimes feel like a visitor on campus; as if I don’t really belong,” Michelle writes in her introduction. “Regardless of the circumstances under which I interact with whites at Princeton, it often seems as if, to them, I will always be a black first and a student second.”

Earlier this year, reporters tracked down the student who was assigned to be Michelle’s freshman-year roommate but transferred out of her room because her mother was unhappy that she had been assigned a black roommate. “Honest to God, Michelle doesn’t even remember that girl,” says Angela Acree about Michelle’s reaction to reporters’ calls on the topic. “She didn’t tell Michelle why she was leaving—she just left. Michelle was like, ‘Aiight!’ ” She laughs. “What I can’t believe is that Princeton actually agreed to move the girl’s room—and they gave her a single! They should’ve put her in a room with eight other white girls and been like, ‘Okay, you happy now?’ ”

“The fact that Barack did not choose a lighter-skinned woman sends a message to me,” says one supporter. Says another, “When I look at Michelle, Barack doesn’t have to be any blacker for me.”

Michelle and Barack’s trajectories crossed at Sidley Austin, a white-glove law firm in Chicago, in 1989. Obama was a first-year associate from Harvard Law School, from which Michelle had graduated the year before. Obama spent three years in between college and law school working as a community organizer in Chicago, so by the time he reached Harvard he was more of a fully formed personality. He moved easily in circles at school where Michelle wasn’t as comfortable, becoming the first black student to helm the Harvard Law Review. He thought deeply about the same conflict that Michelle wrote about in her thesis. “I could work in the black community as an organizer or a lawyer and still live in a high-rise downtown,” he writes, in Dreams From My Father. “Or the other way around: I could work in a blue-chip law firm but live in the South Side and buy a big house, drive a nice car, make my donations to the NAACP.”

At the firm, Michelle was assigned to be Barack’s mentor, but she began with suspicions. “Everyone was raving about this smart, attractive, young first-year associate they had recruited from Harvard,” she’s said. “Everyone was like, ‘Oh, he’s brilliant.’ I said, ‘Okay, this is probably just a brother who can talk straight.’ ”

On one level, it’s obvious that Michelle completed Barack’s American story, the one he told in Dreams From My Father. His fluid identity can startle people. But the couple’s all-American nuclear family—sold with masterful stagecraft on magazine covers from Essence to People to Ladies’ Home Journal—is reassuring. “She’s my rock,” he says, at every opportunity.

To black people, Michelle represents authenticity. It’s hard to overstate black love for her: “The fact that, as a successful black male, Barack did not choose a lighter-skinned woman, as most of them do, sends a message to me,” says a black female supporter at the Pontiac rally. “Michelle is highly sophisticated, yet she comes from the most humble background possible—no one can say she grew up in Martha’s Vineyard and she’s not really black,” says supporter Alicia Nails, a lecturer at Wayne State University, standing nearby. “I’ll tell you my personal philosophy about people: If I want to know who you are, I look at who you sleep with, and who you give your name. When I look at Michelle, Barack doesn’t have to be any blacker for me.”

On their first date, Barack and Michelle ate ice cream from a Baskin-Robbins and went to see Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. It’s a heavily symbolic moment, so perfect that it could’ve been scripted. Afterward, they discussed the scene where Mookie, played by Lee, throws a garbage can through the front window of Sal’s pizzeria to start a race riot. “I think that specific scene represented the character’s frustration with the lack of opportunity and feelings of powerlessness that he saw within his own community,” says Michelle. “And that’s what is so wonderful about the excitement surrounding Barack’s candidacy—his campaign is really about bringing people together to realize their own power in more productive ways.”

Do we want to know which side Obama would have been on, outside that pizza parlor in Brooklyn? He likely would’ve tried to talk Sal and Mookie out of a rash act, though there wouldn’t have been time for that. Michelle doesn’t mention the side he favored on their first date. It’s too loaded a question for a transcendental, post-racial candidate. The feelings unearthed in Lee’s movie, while submerged, are still unhealed twenty years later. The promise of Obama’s campaign, and the notion embodied in their relationship, is to heal those wounds without further pain. But can that really be possible? After 400 years, some doubt is unavoidable.

No one to the left of David Duke would ever admit to being racist. And nearly 70 percent of whites, according to a CBS/New York Times poll from last month, say that America is ready to elect a black president—in theory. But it seems that a lot of white Americans are wondering about what promised land, exactly, the Obamas are going to lead us to. Even if Obama is the kind of black politician that middle-American white voters can get behind, the secret fear is that he could be a black Trojan horse with all sorts of passengers like Wright—or onetime compadres Bernie Mac and Ludacris—peeping out from under the canvas. He could be … Michelle. Or at least what Michelle represents: a smart, angry black person in the White House.

This distrust manifests itself in all sorts of rumors about Obama. Outside a Subway in Atlanta, a bunch of white kids parse Obama’s lineage, at least the fanciful one that they learned about on the Internet. “It’s such a crock that Obama keeps saying he’s going to be the first black president,” says one of them. “He’s half-white, first of all, plus 44 percent Muslim, and only 6 percent African.” (The logic here is that Obama’s paternal line stems from an Arabic tribe.) This doesn’t make Obama any more appealing, though: Apparently, Obama’s uncle is also leader in Kenya of a group that’s “not Al Qaeda, but the other one.” These guys protest that their concerns about him are not about race at all, as one kid, a chin-stroking type studying diesel mechanics, takes over the conversation. “I think we’ve changed our attitudes toward African-Americans in my generation, in the South,” he says, in a measured, calm tone. “But the fact is that if I’m going to elect someone to the highest office in the land, his past needs to be clear.” He looks me straight in the eye, white person to white person. “For us, it’s an issue of trust.”

As I began to finish the reporting for this article, I mentioned to an Obama aide that I was interested in the different ways that Obama presents himself to black and white audiences. The aide hit the roof over this comment, which he claimed was racially divisive, and soon I received a call from Obama’s “African-American outreach coordinator,” who apparently clarifies race issues for reporters when they are perceived to have strayed. “I appreciate what you’re saying,” said Corey Ealons, “but I think it’s dangerous, quite frankly.” He thought for a moment. “The spirit of this campaign is about bringing people together and focusing on the things that are similar about us as opposed to the things that make it different,” he said. “Barack is one of the best political communicators in our history. If you’re somehow saying that he can’t be the same person with all people, that’s certainly not the case.” He paused. “Barack Obama is Barack Obama,” he said.

Obama is the candidate that the Democrats said they wanted—someone who could break down barriers and change the game. At this point in the election process, it’s hard to see the way we move past the race issue, out of the realm of coded discussions and weekly misunderstandings. But there’s a ton of people who aren’t feeling the same hopelessness—they didn’t think that they’d ever see a black presidential candidate in their lifetime, and are pretty thrilled about it. In some of my conversations with African-American voters, excitement is mitigated by a deep apprehension—will Obama really get a chance to lead the country, or will someone shoot him? When you want something so badly, you’re terrified it’s going to be taken away.

The black volunteers outside an Obama event at a middle school in Charlotte, North Carolina, talk about unity and hope, “the urgency of now” and “the spirit of change,” but after five minutes you can’t stop them from talking about the real reason they’re here. Obama is the Messiah, the one to unify all of us. Vanessa Lockhart, a lively woman in a Kente-cloth T-shirt embroidered with the message GOD SENT HIM FROM ABOVE, FILLED HIM WITH PATIENCE AND LOVE, AND CALLED HIM BARACK OBAMA, races through the crowd. “I met Michelle once, and her spirit was so beautiful,” she says. “I gave her a big hug and told her that Barack has an anointing on him by God. Michelle held my shoulders and said, very seriously, ‘Y’all take care of him, now. Y’all please take care of him.’ ”

Off to the side, David Claytor, a barrel-chested man in a red polo shirt, cleans his thin-rimmed black glasses. “This campaign has meant so much,” he says. “One day, I was going door-to-door handing out my Obama stuff, and I came across a house that was flying a Confederate flag. I thought to myself, ‘I don’t know if I want to go to this house. I’ve never been to a house with a flag like that before.’ When I knocked on the door, I saw that the person there was living in abject poverty. Now, I can’t believe that the conservative leaders are gravitating toward a flag, when their people are hurting.”

Claytor puts on his glasses.

“The fact is that it is time for racism to die,” he says. “But racism is a goat. People are lambs, and when a lamb is facing demise, it will lay down and accept it. A goat keeps on squealing, bucking, and crying at the slaughter.”

• Heilemann on the Color-Coded Campaign

• Talking About Not Talking About Race

• How the Obama Generation Will See the World