Before the sun has risen over the Bronx River, an alarm chimes in 17-year-old Grace Padilla’s bedroom. Sliding from the lower bunk, she pads to the bathroom, flips on the light, brushes her teeth, then gathers up her hair into a short ponytail, which she wraps with a long row of black extensions and knots into a tight bun. She’s quick and efficient, with none of the preening one might expect of a high-school junior. At 6:30 a.m., she goes back into the bedroom to wake her 2-year-old daughter.

Along with her grandparents, her mother, her sister, and her child, Grace lives in a small two-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a nondescript brick building in Hunts Point, where nearly half the residents live below the poverty line and roughly 15 percent of girls ages 15 to 19 become pregnant each year. It’s the highest teen-pregnancy rate in the city, more than twice the national average.

“Lilah, wake up,” Grace whispers, leaning in close. Lilah bats her mother away with a tiny hand and nestles up closer to Grace’s own mother, Mayra, who had moments before returned home from her night shift as a cashier at a local food-distribution center and slipped, exhausted, into Grace’s place in the bed.

“Come on, let’s go get dressed,” Grace pleads, pulling her daughter from under the covers as Lilah begins crying, flailing her arms and legs.

“Come on,” Grace begs. She fights to keep her mounting frustration in check and then counts down the seconds before she’ll make Lilah go stand against the wall, her usual form of punishment. “Five … four … three … two … one.”

The threat is enough. Lilah’s body goes slack, her screaming dissipates to a whimper. Grace is able to wrestle her into the clothes she’d laid out beforehand. But the child’s screams have woken Grace’s grandparents, who are now in the galley kitchen, arguing in Spanish. Her grandfather has Alzheimer’s. He accidentally makes decaffeinated coffee, which infuriates his wife.

At 7:20, Grace smoothes a tiny hat over Lilah’s curls, bundles her into a coat, then jostles schoolbooks into a bag. In the empty lot across the street, a rooster starts to crow.

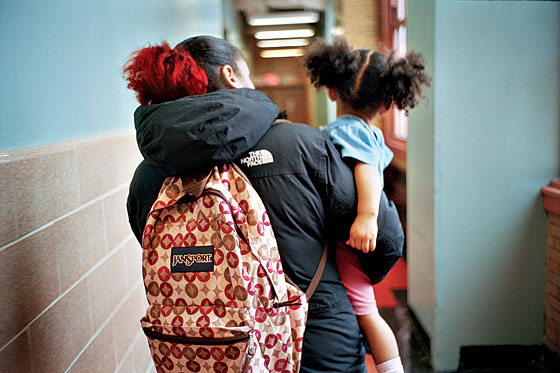

When Grace arrives at Jane Addams High School for Academics and Careers, she joins the daily parade of mothers—pushing strollers, grasping the chubby fists of toddlers, perching bundled babies on cocked hips—making their way to basement room B17, the headquarters of the school’s Living for the Young Family Through Education (LYFE) center. Run by the Department of Education, the LYFE program operates in 38 schools in the five boroughs, teaching parenting skills and providing on-site day care to teen parents who are full-time students in New York City’s public schools. Jane Addams hosts one of the most active branches in the city, with sixteen mothers currently in the program.

While the students sign in on a clipboard, social worker Ana C. Martínez flits among them with her checklist of concerns. Is this baby eating enough? (Yes.) Does that one still have a cough? (No.) When will the heat be turned back on in one young mother’s apartment? (Uncertain.) If it isn’t soon, has she considered going to a shelter? (She has.)

“How’s the baby?” Martínez asks Grace.

“She’s fine,” Grace answers.

Satisfied, Martínez turns her attention to Lilah. “Can I get a hug?”

“No,” the child replies coyly, pretending to hide behind her mother’s legs.

“Pretty please?”

Lilah finally concedes, jumping into the woman’s arms.

Martínez laughs. “We have to play that game every morning, don’t we?”

The girls cluster around a table laid out with bagels and jam, which Martínez serves every morning, both to entice her charges to be at school on time and also to make sure they get enough to eat (“Some don’t at home,” she clucks). She admits that the LYFE program, which serves 500 families and costs taxpayers about $13 million a year, has its naysayers, people who think that it makes life too easy for the mothers and diverts money from students who’ve made more-responsible choices. “But the reality is, teens are having kids, and we’ve got to work with them,” she says. “They’re entitled to an education.”

Grace greets Jasmine Reyes—a soft-spoken senior whose 2-year-old daughter, Jayleen, is Lilah’s best friend in day care—before going over to peer at Nelsy Valerio’s infant. When Iruma Moré enters the room with her 8-month-old daughter, Dymia, Grace beelines for the baby, unwrapping her from a pile of blankets.

“Dymia, Dymia, Dy-mi-a,” she chants, bouncing the child on her lap. “She’s so little,” Grace marvels wistfully.

Iruma giggles. “I try to feed her all the time,” she says, as she drops into a chair next to a locker crammed full of diapers. Though all four of Iruma’s older sisters were teen mothers, she didn’t know her school had day care until her sophomore year. “I started seeing the mothers coming in with their babies and stuff, and I always used to wonder where they take them,” she says. One day, she looked through a doorway and it was like peering into a magic cupboard—a roomful of babies with soft skin and fine hair. Iruma thought she might like to have one of her own. By her junior year, she was pregnant. “I wasn’t using nothing, no protection, so I mean, I knew it was gonna come sooner or later.”

The nursery is a clown’s paradise, brightly painted and well outfitted with funds donated by makeup artist Bobbi Brown. (In addition to the traditional high-school curriculum, Jane Addams teaches a number of vocations, including cosmetology, which Grace is studying.) Grace and Iruma each commandeer a crib and begin to strip down their daughters to their underwear, so that a caretaker can check the children for marks. Then the mothers fill out a form about when their child last ate, the child’s mood, how the baby has been sleeping. Just before the bell rings for second period, they leave the nursery and head upstairs to school. For the next seven hours, they’ll get to be kids again themselves.

Grace got pregnant in January 2006, less than a month after her 14th birthday and soon after she lost her virginity to a 15-year-old boy from the neighborhood named Nikko Vega. He was the only person she’d slept with, or even wanted to. After he broke up with a girlfriend (“A ho,” Grace sniffs), she began cutting her eighth-grade classes to meet him at his apartment. Even then, she had full curves and a round and inviting face. She was normally sweet, but if pressed, she could fire off a string of expletives so fast the words blurred together. Nikko liked that about her. One day, the two of them found themselves playing more than Nintendo, and they just let it happen.

“It was heat-of-the-moment stuff,” Grace says of having sex for the first time. Getting pregnant wasn’t even on her mind. But it was on Nikko’s: “A couple of hours after, I was thinking, like, Damn.” He eventually asked Grace if she should go on birth control, but they knew that would make her mom suspicious. They decided to take their chances, though it bothered Nikko to be so reckless. “A lot of people I knew had kids young, and I didn’t want to be one of them,” he admits. He had hoped to go to college on a football scholarship, had even made a pact with his friends to put off fatherhood. “Like, ever since we were younger, we all spoke about, ‘No kids.’ All of us.”

“It didn’t work,” Grace says archly. “Everybody he grew up with has a kid now.”

Grace didn’t know she was pregnant for months. She didn’t get morning sickness, headaches, or cramps. She still did step dancing, played football after school, rode roller coasters when her mom took her to a theme park, fit into her regular clothes. She hadn’t been having her period long enough for its absence to be a major cause for concern. When she went to a neighborhood clinic to get tested, just in case, and the results came back positive, she was shocked. “I didn’t really know what to do,” she says. “I didn’t know what to ask. I was just like, ‘What?’ ”

When she told Nikko, he walked away without saying a word, but a couple of hours later, he returned, driven back by the hangdog devotion he has for Grace and by fear of her disapproval. She told him that she wanted to keep the baby and that she was happy about the decision, “in a sad sort of way.” She loved babies, but she wasn’t sure what she was getting into. To the extent that he could be there for her, an extent that even he understood to be meager, Nikko said he was onboard.

It took Grace a month to work up the nerve to tell her mother. When Mayra came home from work one day, Grace, her older sister, Samantha, and her cousin were sitting in front of the building waiting for her “like there was a funeral.” In the elevator ride up to the apartment, Mayra looked from one girl to the next. “Which one of you is pregnant?” she asked. She thought Samantha would answer, but when she didn’t, the realization set in that it was her younger daughter who was in trouble.

“How could you?” Mayra screamed, standing in their living room, shaking with anger. “How could you? You see our situation, you see what I have on my plate. How could you be so selfish?”

Grace ran to her bedroom, sobbing. Mayra stayed in the living room, sobbing. Mayra’s own mother walked in the door and demanded to know what was going on.

“Your granddaughter,” Mayra wailed, “your 14-year-old granddaughter decided you needed to see a great-grandkid.”

“Oh my God,” the old woman said. “¡Ay, Dios mío! ¡Ay, Dios mío, ayúdenos!”

For a month, Mayra cried every day. Having gotten married at 16 and had Samantha at 17, she was loath to become a grandmother at 36. She had asked Grace repeatedly if she had started having sex, and the girl had always denied it. Between her parents and her own children, the apartment was already overcrowded, and money stretched thin. She threatened to send Grace to live with her father, who had left the family a decade ago. For years, they hadn’t been able to track him down. Now he had a new family in Philadelphia, and Grace had been in cautious contact. But when they called to tell him about the pregnancy, he made it clear that she wasn’t welcome. Grace hasn’t spoken to him since.

Mayra was surprised to find herself seriously considering abortion as an option. The South Bronx has a high birthrate in part because in this largely Hispanic and Catholic community, the idea of terminating a pregnancy meets with such intense disapproval. Her mother told her that she would not be able to live under the same roof if they went through with it, but Mayra didn’t see how Grace could manage to raise a child, nor did she want to put her daughter through the difficulty of labor only to give the baby away. Grace guessed that she was about four months along and agreed to visit an abortion clinic. The sonogram showed that the baby was due in ten weeks.

“Ten weeks?” Mayra asked. “This is a 14-year-old who’s been to theme parks, eaten junk food the whole time, had no prenatal care. Ten weeks? I don’t know what this baby’s gonna be like.”

The nurse nodded sympathetically, but there was nothing to be done. “There’s nowhere in this country where they’ll do that abortion at seven months.”

Mayra set about preparing for the baby. She arranged for Grace to be enrolled in Jane Addams, the closest school that had a LYFE program. She put a call out to friends and family for a crib, a stroller, secondhand baby clothes. She started making doctors appointments, pleading her daughter’s way into clinics that didn’t have openings until after the baby was due. Grace looked so young when she brought her in, no one could believe she was the one who was pregnant.

Grace’s water broke in the hallway of Jane Addams the second week of her freshman year, a full month before her due date. Thinking she had wet her pants, she called her mother from a bathroom stall.

“Um, I want to go home,” she said when Mayra picked up.

“Why? What happened?”

“My pants are all wet.”

“What do you mean your pants are all wet? Did a car splash you or something?”

“No. Like, they’re all wet. Like, I went into the bathroom, and they’re all wet.”

“Oh my God,” Mayra cut in. “Your water broke. Oh my God! You’re gonna have this baby in that school!”

When Grace arrived at Albert Einstein hospital, she was having contractions. Her mother stepped outside to calm her nerves with a cigarette, and Grace took the moment alone to ask her doctor if it was possible that she might die in childbirth. He reassured her that the chances were infinitesimally slim. “He sugarcoated it,” she says. “He was a nice guy.”

By the time Nikko arrived the following afternoon, Grace was in the throes of “the worst pain I ever felt in my life,” she says, gasping just at the thought. She refused to allow him in the room. “I was in so much pain I really just wanted to kill him. I said, ‘I advise security, doctors, nurses, everybody on this floor, if that man reaches this room, it’s gonna be chaos, because this is all his fault.’ ”

On Sunday, September 17, 2006, at 2:55 a.m., Delilah Joli Vega was born, alert and healthy.

At the McDonald’s on Prospect Avenue, teenagers crowd the counter, munching fries and competing for attention, the boys with their hooded sweatshirts pulled down low over their eyes, the girls in tight jeans and baby tees, nameplate jewelry shimmering, hair ruthlessly slicked back into high ponytails. As Iruma orders a pile of cheeseburgers and two Happy Meals, Grace and Jasmine drag high chairs up to the table and settle in with Nikko. The conversation is no different from that at any other table in the place, except for the constant interruption. There’s drama going down on Grace’s block—“Dumbass Samantha was talking about, ‘Oh, if Sasha did punch A.J. in the face, it wasn’t ’cause A.J. hit her, it was over Killah …’ ”—but she can’t focus on the story with Lilah sending golden arcs of boxed apple juice into the air.

“Lilah, you’re spilling the juice,” Grace points out. “You’re. Spilling. The. Juice.”

Jayleen, Jasmine’s daughter, looks over at Lilah, then squeezes her own juice box with vigor.

“You must want to get smacked,” Grace tells her, raising her eyebrows before turning to the girl’s mother. “I been telling you about that, Jasmine.”

“Later, later,” Jasmine pleads, not in the mood for a parenting lesson. But the fact is the mothers often act as a check on one another, imparting what parenting wisdom they have, holding one another to a certain standard. Grace, particularly, prides herself on her parenting skills. She’s observant. She’s strict. Her mother, Mayra, taught her how to take care of Lilah but refused to do the tasks for her. Grace was the one who changed Lilah’s diapers, fed her, got up in the middle of the night when she cried. “She’s not Baby Alive, is she?” Mayra would ask. “There’s no off-button on her.”

Having teenage parents does mean that Lilah is prone to mimic teenage behavior. “Her attitude is serious,” says Grace. “She’ll be like, ‘Mind your business.’ Mind my business? You better be talking to the milkman! I love her, but sometimes I just want to bop her on her head.” But the good manners Lilah displays in front of company—if not always at home—testify to Grace’s efforts.

Even now, as Lilah eyes the chicken nuggets that Iruma has been tearing into bite-size chunks for Dymia, she doesn’t reach out and take one. “Hee dat icken, Mommy?” she asks politely.

“I see that chicken,” Grace answers. “But you asked for a burger, so now you’re gonna eat a burger.”

“She didn’t ask for a burger. You said she wanted a burger,” Jasmine points out. “You’re mad mean.”

Grace shrugs off the comment, as a girl from their school pauses on her way past their table.

“Hey! What’s up, baby?” she coos at Dymia before turning to Iruma. “She’s getting so big. Oh my God!”

Iruma pushes her glasses up on her nose and smiles contentedly. “Yeah, she getting big.”

“Oh my God, you’re so cute!” The girl stares at Dymia, shaking her head in amazement.

In the South Bronx, the stigma of having a child at a young age is remarkably absent, not just because teen parenthood has long been pervasive but also because the family structure is such that children often grow up raising younger siblings, nieces, and nephews. Adding a child of their own into the mix doesn’t seem like it will change much in terms of daily routine, but it does feel like a rite of passage, a one-way ticket to adulthood. Motherhood cements a girl’s fertility, her femininity. Louder than any clingy top or painted lip, it broadcasts that now she’s a woman. And for some girls, that’s appealing. When The Tyra Banks Show did an online survey of 10,000 girls across the country, one-fifth of them said they wanted to become teen moms. The latest Centers for Disease Control report shows a 3 percent increase in teen pregnancy in 2006 after more than a decade of decline. At Jane Addams, round bellies orbit the hallways like planets. The school doesn’t keep track of pregnancies, but according to the attendance officer, one week this spring, seven girls out of a student body of about 1,500 were out of school to give birth.

Grace got pregnant at 14. She told Nikko that she wanted to keep the baby and that she was happy, “in a sad sort of way.”

The mothers watch as the girl from school continues on her way, joining a booth where a group of teenagers have piled in together, plopping on each other’s laps, laughing loudly at each other’s jokes. None of them have children. They seem not to have a single care. The chasm between being a parent and being a kid was difficult to intuit until it was crossed. Now Grace knows it well. When Nikko once teased her about all the fun she would have without him if she went to college, she leveled a cold stare at him and asked, “How am I gonna have fun in college with a child?”

Iruma fishes her cell phone out of a bag and presses a few buttons. Hip-hop starts to blare from the little speakers, setting a more festive mood. The moms relax. Jayleen and Lilah bounce in time to the music.

“Jayleen, you want to dance for everybody?” Jasmine asks. “You want to get on the table and dance?”

Jayleen tries to climb out of her high chair, and Jasmine lifts her up onto the bench, where she plants her feet and shakes her little bottom back and forth.

“Oh, she gotta donk, she gotta donk,” Jasmine chants, as Jayleen’s dance grows increasingly outrageous. The moms laugh.

Sometimes it’s hard not to act their age. “You need to be adult and mature, but you’re still young,” says Grace. “Adults have fun all the time. They still joke, they still laugh. They can’t take your kid away just because of that.”

When Grace gets home from school one afternoon, her grandparents have two eyes of the gas stove burning to drive away the apartment’s chill. She steers Lilah away from the flame and to the refrigerator, where she allows her to choose a snack. Lilah points at a pitcher of red liquid, and Grace fixes her a bottle, waiting for Nikko to get home from the GED program he started the week before. When he does, he waves a sheet of loose-leaf paper in front of her. It’s his first assignment, a short essay on why he should be a candidate for the program.

“I need to finish school for my 2-year-old daughter,” he starts off in an even hand. “I need to finish school for her because she follows everything that I do, and I feel that it is time for me to step up to the plate.” At the bottom of the page, his teacher has written “good ideas, good motivation” and given him a B-plus. Grace seems pleased. “Oh snap, babe. Now what are you gonna do to get an A-minus?”

She’s only half-joking. Even if it is sometimes misplaced, Grace has a highly evolved sense of propriety. She expects to be treated a certain way, expects Nikko to embrace his responsibilities as a father. Her loyalties now are to Lilah, and her world is delineated: There are the players and hustlers and birds, people best avoided; then there are the “cousins” and títís and “brothers,” people she may not be related to by blood but who do well by her and her daughter. She’s not quite sure yet where Nikko falls. “He be all right,” she says.

It took a long time for Mayra to accept Nikko as a de facto member of the family. It wasn’t just his role in the pregnancy—she understood that Grace was equally at fault—it was his own neglectful upbringing that gave her pause. She refused to have his name listed on Lilah’s birth certificate until her own mother interjected. “You’re gonna leave her birth certificate just blank under father, like she doesn’t know who her child’s father is?” the older woman asked, horrified.

Since Lilah was born, Nikko has spent a smattering of nights in jail, mostly for getting in neighborhood fights or, as he says, “being in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Because his mother did not force him to go to school, he has not a single high-school credit. When Mayra took him to family court for child support (a requirement of the LYFE program), Mayra told the judge that she didn’t expect any money from Nikko, that she would prefer he get an education rather than a job now, so that he could support his child later; but the judge still awarded them $25 a month—less than the cost of a box of diapers—which Nikko’s mother agreed to pay until her son turned 18. Grace and Mayra have still not seen a cent.

In the end, though, it was hard to keep blaming Nikko, a child, for what Mayra saw as his mother’s failings. When he didn’t have a winter coat, she bought him one. When he was hungry, she fed him. When his mother kicked him out after a fight with her boyfriend, Mayra temporarily let him stay with them. Over time, he grew on her. “I basically showed her a lot of respect,” says Nikko. “A lot of butt kissing,” corrects Grace. Mayra realizes that, in his capacity, he is a good father: He’s present. Though other girls are still dating the fathers of their children, Nikko is the only boy who visits the LYFE center. A certificate stating that he completed LYFE’s fatherhood-training program hangs in a frame over Grace’s bed. “The only reason I don’t press it is because this baby knows who her daddy is,” says Mayra. “And she loves her daddy.”

Still, both Mayra and Grace find their patience sputtering. In the three years since Grace got pregnant, Nikko hadn’t held a single job or completed a single class. Mayra sees the writing on the wall. She knows that the statistics are not in Nikko and Grace’s favor: Only 40 percent of teenagers who have children get their high-school diplomas, and 64 percent of children born to unmarried high-school dropouts live in poverty. “Life isn’t about you anymore,” Mayra is quick to inform him. “You brought someone else into this world that you have to care for. If you’re gonna be that type of person that’s gonna just not do nothing—and because of that, statistics is gonna land you back in jail—you may as well say bye to them now while Lilah’s small and can get over you fast. Because this baby’s not visiting nobody in jail.” At the beginning of this year, to make good on her word, she gave him one month to prove to her that he was in school or had landed a job. Right at the deadline, he signed up for his GED.

Sometimes Grace feels that she’s leaving Nikko behind. She talks of going to college, studying business, opening her own beauty salon, getting her child out of Hunts Point, away from the “hustlers and divas.” She expects that there will come a day when she alone is responsible for providing for Lilah. “You can hope, we can all hope that Nikko’s gonna do something to better himself and want to be there and provide for his family,” Mayra tells her. “But the fact remains, if he doesn’t, he wouldn’t be the first boy. You wouldn’t be the first single mother.”

One evening early this spring, the young family has the Padilla apartment to themselves. Mayra sleeps soundly behind the closed door of the bedroom, resting up for her night shift at eleven. Grace’s grandparents are at church, her sister out with friends. At times like these, Grace likes to pretend the apartment belongs to her and Nikko, that she doesn’t live with her mother and he doesn’t crash at a friend’s place, that they’ve managed to make a life for themselves and Lilah on their own.

Nikko prepares a bowl of popcorn, while Grace flips through channels on the TV, stopping at a music video she knows Lilah likes. The little girl follows along with the dance in the best rendition a 2-year-old could possibly muster, stroking her hips as they wiggle furiously and then flapping her wrists like a drag queen. When she looks behind her to make sure her parents are watching, Nikko and Grace laugh at her presumption. As parents, they share an easy rapport. She teases and prods him gently; he defers to her with a good-natured grin.

Later, there’s homework to be done. Grace has a field trip tomorrow, so her load is light, but Nikko struggles to write an essay on the three branches of government. Once he finishes his GED, he’s hoping to enroll in junior college. Grace pulls out her U.S. history folder, shows him a few photocopied papers, then goes into the kitchen to heat up frozen chicken patties.

After they eat, she gives Lilah a bath, crouching by the bathtub and allowing her daughter to splash around as long as she likes. “You a monkey,” she says, laughing as Lilah dunks her head under the water and then shakes out her curls. “When she was a baby, the funnest part was the bath because her faces were just priceless.” While Nikko heats up a bottle of chocolate milk, Grace towels Lilah off, rubs her down with lotion as the child tries to squirm out of her grasp—“She likes running around naked”—and dresses her in a diaper and footed fleece pajamas. Nikko puts his homework aside to give Lilah her bottle, stretching her out across his lap and rocking her gently. He waits until she’s asleep to kiss Grace good-bye.

“Love you, babe,” he says.

“Love you too.”