Sometime early Sunday morning this Memorial Day weekend, a work crew from the New York City Department of Transportation will arrive in Times Square. Waiting for a pause in traffic, the team will close off Broadway at 47th Street, directing southbound cars east to Seventh Avenue. In the weeks to come, construction workers will refashion the next five blocks of the boulevard, turning one of the world’s most congested stretches of asphalt into a 58,000-foot pedestrian plaza. The same will happen a few blocks south, where another stretch of Broadway—from 33rd Street to 35th Street, at Herald Square—will be closed to cars and, by fall, dotted with café tables free for public use.

This simple but dramatic act will amount to bypass surgery on the heart of New York. It will become the most visible component yet of Mayor Bloomberg’s citywide attempt to make New York’s streets calmer, greener, and safer. And it will establish the front lines of a growing movement to tilt the balance of asphalt power away from the automobile and toward cyclists and pedestrians.

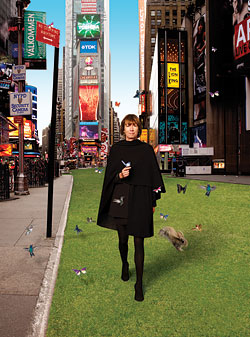

On a recent weekday, Janette Sadik-Khan, the city’s Transportation commissioner and the woman who dreamed up this plan, is standing at the heart of Times Square and surveying the mayhem around her. Though it is late morning and nothing like the Hieronymus Bosch tableau of the evening rush, traffic is still crawling and honking through the bizarre convergence of Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 45th Street. Pedestrians are spilling into the street. A biker shoots up Broadway riding in the wrong direction.

“From a transportation perspective, Broadway has been a problem for 200 years,” Sadik-Khan says. Fifty-thousand cars pass through this point every day, but the knot formed by the intersection of three streets limits traffic speed to roughly four miles per hour. And then there are the people—about 356,000 of them marching through Times Square daily, from aggravated office workers to bewildered midwestern tourist families with roller suitcases. This stretch of Broadway is 140 percent more dangerous than comparable stretches of a midtown avenue.

“You can try to tweak it with a little signal change here, maybe a traffic lane there,” Sadik-Khan continues. “But nothing has worked because you’re not reaching the fundamental problem, which is that midtown is basically broken. There’s just not enough space for people.”

People, however, are not all the same. You’d think that closing Broadway to traffic would be seen as a grand egalitarian gesture. Returning a public amenity like the street to the perambulating masses should be a source of democratic harmony. And yet it’s not. Plans like these never are. Perhaps it’s the sense of a centralized hidden hand at work. Or maybe it’s the fact that the streets are the ultimate shared resource, giving everyone a proprietary feeling about them. But redrawing the map of the city invariably stokes suspicion and resentment, and doing so at its absolute nerve center is being read by some as an act of provocation.

Sadik-Khan has been at her job long enough to know that one does not rearrange traffic in midtown lightly, so she has grounded her Broadway plan on assiduous analysis and computer modeling of traffic flow. She has managed a sophisticated PR campaign that has paid off with support from both the Times and the Daily News, as well as the business-improvement districts.

But even though her models suggest that simplifying the three-way intersections will enhance circulation, she has yet to convince many of the players who use Times Square the most. There are the practical complaints: Small-business owners worry that traffic will clog the side streets, making it harder to handle deliveries and pickups. Cabbies and theater owners are similarly concerned about dropping off ticketholders. Then there are the more abstract objections that have to do with a Transportation commissioner many perceive to be an anti-car radical. “Broadway in theory is a good idea, but unfortunately what’s a good idea for the city is not always a good idea for all the stakeholders,” says John Liu, an ambitious young City Council member from Queens who chairs the council’s Transportation Committee. For people like Liu, the Broadway plan is about something more than several blocks of midtown traffic. It’s a clash of values. “There is a sense of the elite telling the everyday people what’s good for them, and that’s simply not appreciated,” Liu says. “I think it can no longer be ignored, the demographic groups calling for these changes versus the demographic groups that protest.”

Between her plans for Broadway and her smaller interventions scattered across the city, Sadik-Khan has unwittingly touched off New York’s latest culture war, a street fight of sorts. To her supporters, she is a heroic figure of vision and inspiration—the woman who tamed the automobile and made the city safe for bicyclists. To her opponents, she’s the latest in an extensive line of effete, out-of-touch liberals: the hipster bureaucrat. All parties would agree she’s an unusual Transportation commissioner, a title that may call to mind a paunchy, mustachioed male with a penchant for dirty jokes. Sadik-Khan is a stylish, young-looking 49-year-old whose skirts don’t always pass her knees. (“I am a gay man, but I appreciate a sexy-looking woman!” says her friend the former restaurateur Florent Morellet.) She lives in the West Village and often bikes to work. She frequently enlists celebrities like Jay-Z, Diane Von Furstenberg, and David Byrne to headline DOT press ops. “She’s a rocket,” says her friend and City Planning director Amanda Burden. “Courageous, determined, hilarious, fearless, and exuberant. She laughs like no other person I deal with in the entire city.” She is also the most powerful advocate of the city’s burgeoning biking scene, heretofore a largely countercultural force. (“Biking is the new golf,” she’s been known to tell Wall Street crowds.)

Starting next week, the Times Square portion of Broadway will be closed to traffic. By the fall, it will be converted to a 58,000-square-foot pedestrian plaza.Photo: Courtesy of the New York City Department of Transportation

Before Sadik-Khan’s appointment in 2007, the job of the Transportation commissioner was understood to be fairly straightforward. “Transportation engineers are sort of like plumbers with college degrees,” says Paul Steely White, director of the cycling activist group Transportation Alternatives. “They see their job as solving the clogs and keeping cars and trucks moving.” For a string of previous commissioners, including her immediate predecessor, Iris Weinshall, this meant fixing, expanding, and streamlining roads—all in the service of managing flow.

Sadik-Khan’s approach to traffic management is not as extreme as it may first appear. Many transportation experts now recognize that adding more lanes to a traffic-clogged road is a poor long-term solution for gridlock, because over time more lanes just attract more cars. (This, in a nutshell, is why cities with the most highways tend to have the most traffic.) Sadik-Khan’s Broadway plan, which reduces lanes and improves streetlight timing, reflects this new evolution of traffic theory. Eliminating the three-way intersection at 34th Street, for example, means that cars on that street and on Sixth Avenue will no longer have to sit through green lights on Broadway; the DOT predicts that this will shorten wait times by nearly a third. Southbound drivers on Seventh Avenue should expect a 17 percent improvement in travel time between 59th Street and 23rd Street. Northbound motorists driving up Sixth Avenue can supposedly look forward to a 37 percent improvement.

But even though the Broadway plan has been pitched as a way to ameliorate traffic, it’s apparent when touring Times Square with Sadik-Khan that the planning problem that most animates her is not car congestion but people congestion. “This is a plan to pedestrianize a street, not to mitigate traffic,” says someone who has discussed it with DOT officials. “This was a plan about greening New York, outdoor space, and seating. It was almost a happy accident that they found that traffic could be mitigated.”

In this offhand remark one can see Sadik-Khan’s truly revolutionary vision. She has fashioned herself the city’s streets commissioner, rather than the city’s traffic commissioner, and has not been shy about imposing a vision of the 21st-century street that seizes it back from the automobile. “One of the good legacies of Robert Moses is that, because he paved so much, we’re able to reclaim it and reuse it,” she says. “It’s sort of like Jane Jacobs’s revenge on Robert Moses.”

Her acts of revenge are now visible throughout the city. A new traffic pattern in the meatpacking district has opened up a large pedestrian space protected by planters and bollards. A similar conversion has taken place in Dumbo. Two lanes of Broadway have been closed to traffic between Times Square and Herald Square since last August, allowing for a new bike lane and a pedestrian esplanade with café tables—a preview of what’s to come this summer. Her most visible markings are the bicycle lanes you see everywhere, 180 miles more of them since 2006. These are small-scale interventions, but they serve an ambitious strategy. “I am basically the largest real-estate developer in New York City,” Sadik-Khan likes to say at public events. For a Jacobs disciple, she has a lot of Moses in her.

When Weinshall stepped down in 2007 to become a vice-chancellor at the City University of New York, it wasn’t clear what Mayor Bloomberg wanted in her successor. The mayor hadn’t shown much interest in innovative transportation policy and had been content to let Weinshall—a Giuliani appointee (and Chuck Schumer’s wife)—run a status-quo operation. The DOT’s last bicycle-program director, Andrew Vesselinovitch, had quit the year before, writing in the Times a month after he left that “our efforts were so rarely encouraged, and so often delayed, that I came to the conclusion that the department is not truly committed to promoting bicycling in New York.” That may have been mostly Weinshall’s doing, but some say the resistance came from higher up. “I’ve heard from DOT people that the mayor really doesn’t like bikes,” says one biking advocate. “He has that Upper East Side–pedestrian attitude. Getting run over by a Chinese deliveryman—that to him is a ‘cyclist.’ ”

On the other hand, Bloomberg was putting the finishing touches on PlaNYC, a blueprint for expanded green space and a reduced carbon footprint for the city that would require substantial rethinking of key government agencies—especially transportation. PlaNYC was a lot more radical than the mayor got credit for at the time, and a serious departure from how he thought of the city’s physical landscape. It also demonstrated Bloomberg’s affinity for symbolic gestures (like the gimmicky idea of planting 1 million trees). Not only were Sadik-Khan’s ideas about public transportation and open space consistent with PlaNYC, but she, too, intuitively understood the power of symbols—a café table or even a bicycle—to illustrate an appealing vision of the city’s future.

Last summer, the Department of Transportation remapped Broadway above 23rd Street. Downtown traffic that used to cross Fifth Avenue now merges with it on the west side of the street.

1. A dedicated bike lane runs to the east of three lanes of Fifth Avenue.

2. Three lanes of traffic were converted to 41,700 square feet of public space.

3. Café tables are maintained by the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership.

4. The discontinued sections of Broadway and Fifth Avenue were painted over with an epoxied gravel surface. Photo: Courtesy of the new York City Department of Transportation

Sadik-Khan had her own prior experience in city government, but it was the mind of an activist, not an engineer, that led her to transportation. “I’ve always been interested in politics, and that probably stems from conversations around dinner tables,” Sadik-Khan told me over breakfast in the West Village. Her father was a managing director at Paine Webber, but she seems to have been most inspired by her mother, an environmental activist who has worked with quality-of-life groups like the Citizens Housing and Planning Council. From her, Sadik-Khan inherited a green streak that dovetailed with a passion for transportation—which, after all, involves core questions about energy and the environment. (Sadik-Khan’s mother also covered City Hall for the Post, presumably affording her daughter a minor degree in political intrigue.) She earned a law degree from Columbia and briefly worked as a corporate lawyer before joining the Dinkins administration in 1990 and quickly becoming his top transportation adviser. After Giuliani’s election, she went to Washington to be deputy administrator of the Federal Transit Administration. By 1999, she was a senior vice-president of the international engineering firm Parsons Brinckerhoff, traveling the world and swapping ideas with just about every transportation thinker who matters.

On some level, Bloomberg may ultimately have been attracted to Sadik-Khan’s pure force of personality. She shares with him a quick and impatient temperament, a disdain for bureaucratic muck, and a soft spot for visionary, internationally influenced thinking. But when the appointment was made, some entrenched members of the city bureaucracy were skeptical. “The transportation world is a small, cozy, and generally a pretty dreary crowd,” says one city transportation insider. “So when you have a woman who is younger and dresses well, sure there’s going to be some teeth-gnashing among the men in their sixties Brooks Brothers suits.” Sadik-Khan stoked these concerns when she quickly hired several prominent figures from the ranks of the activist class who had long clashed with DOT. Her chief policy adviser, Jon Orcutt, for example, is a former executive director of Transportation Alternatives, which was founded in 1973 as a confrontational pro-cyclist group and evolved into a more mainstream advocacy outfit. “The agency had been at complete odds with the activists,” says one former department employee. As Sadik-Khan brought in her team, “there was some sense that the inmates had taken over the asylum.”

The Broadway plan is about something more than several blocks of midtown traffic. It’s a clash of values.

But Sadik-Khan tried to be inclusive, sitting down with her new colleagues and other city-government officials to explain her vision—fast and bold expansions of space for bikers and pedestrians—and offer them a more inclusive role in it. “She integrated old and new staff,” says one DOT employee. “It wasn’t like she came in and axed everyone who had been here for ten years.” One success story was Michael Primeggia, a 30-year DOT veteran who’d spent half of his term as the department’s traffic-management chief. Some transportation activists called Primeggia “Dr. No” because he epitomized the city’s entrenched car-first attitude. “He was as ornery and curmudgeonly as you can get,” says Sam Schwartz, a Koch-era traffic commissioner who calls Primeggia his protégé. But Primeggia credits Sadik-Khan for including him in her plans, even bringing him along on a spring 2007 fact-finding mission to Copenhagen. Amanda Burden, who also joined the trip, remembers watching him explore the Danish urban planners’ paradise: “I saw Mike Primeggia on his knees measuring the width of the bike lane, and I said, ‘I have died and gone to heaven!’ This agency is transformed!”

One of Sadik-Khan’s first projects was the creation of what she calls “the complete street.” She built a prototype along Ninth Avenue in Chelsea, where a protected bike lane runs between the sidewalk and parallel parked cars, thus narrowing the avenue by one lane for motorists. At 14th Street, a narrow pedestrian strip is dotted with tables and chairs. “You can accommodate bikers, cars, pedestrians, and create open space,” she says one chilly, damp morning, as she walks by the tables. “There’s a guy, despite the weather, sitting there, headphones on, enjoying a little public space. There’s really a hunger for more space in the city, and we’re doing everything we can to quench that.”

The new Ninth Avenue layout was inspired, as are many of Sadik-Khan’s ideas, by another city—in this case, the pedestrian wonderland of Copenhagen. “I am an unabashed thief,” she says. “I basically go around the world borrowing ideas from other places.” One early trip took her to Bogotá, Colombia, where the city’s former mayor, Enrique Peñalosa, led her on a five-hour bike tour. But Copenhagen, often called one of the world’s best-designed and most livable cities, has had a particular influence over her. The city center features eighteen car-free areas and several pedestrian promenades, all stitched together by an elaborate network of bicycle and pedestrian paths. The city impressed Sadik-Khan enough for her to give its mastermind, the 72-year-old urban planner Jan Gehl, a consulting contract. (She raised funds for his fee privately, through private foundations.) Gehl did not always mesh seamlessly with city bureaucrats, but his influence can already be felt, especially on the Chelsea bike lanes and the Broadway redesign.

Gehl is also a believer in acting incrementally—implementing modest changes that demonstrate a larger vision. Which is why the bike lanes in Chelsea initially ran for just a few blocks on Ninth Avenue (and have recently been expanded up to 31st Street, and on Eighth Avenue). The Broadway plan was preceded last year by the closure of two lanes. The Summer Streets program shut down Park Avenue for three Saturdays last August, and was judged enough of a success that it will be replicated this year.

But if politics calls for moving in increments, it can also call for speed. Sadik-Khan moves fast, sometimes making changes literally overnight in guerrilla-style operations conducted with little more than paint cans and a few planters. (For this reason, her projects tend to be quite inexpensive.) “In New York, everybody’s an expert, everybody’s got a point of view, and everything involves delay—and sometimes litigation. So whenever possible, Janette has taken a fait accompli approach,” says Bob Yaro, president of the Regional Plan Association. He recalls how the city created a new plaza from a small sliver of asphalt at Madison Square, where Broadway awkwardly intersects 23rd Street and Fifth Avenue. “At 11 p.m. one night, they started putting out bollards and chairs and striping paint, and the next morning—it was just, done deal!” (The result was 41,700 square feet of new public space.) “I’ve dealt with DOT since 1982, and this is the strongest team at the top in terms of getting things done,” says Dan Biederman, president of the 34th Street Partnership. “This is breakneck speed.”

That speed is possible in part because, while Sadik-Khan takes pains to involve local community-planning boards, she doesn’t run her projects past the City Council. She is careful to line up allies, but she doesn’t always court those whose input might cause trouble. So while according to Biederman she started having off-the-record meetings about the Broadway plan months before going public with it, taxi-industry representatives and some Broadway theater owners say that they were consulted barely or not at all. Her approach, says Liu, “has not been all-inclusive. It has been selectively inclusive.” Says one person who has followed New York City transportation policy for many years, “I’ve been in this business a long time, and I am absolutely shocked to see how a group like Transportation Alternatives is literally writing transportation policy in the city of New York—unchecked.”

Sadik-Khan’s sudden moves can have contentious results. Hasidic-community leaders near new bike lanes in Williamsburg complained about scantily clad women cycling past their homes. After angry residents intentionally blocked the lanes with their cars, a self-proclaimed group of “bike clowns” rode through the area in pointed hats handing out fake parking tickets and staging slapstick pileups. Meanwhile, at a recent meatpacking-district community-board meeting, nightclub owners complained that traffic-calming measures are slowing taxi traffic, and a debate ensued over whether the bollards at Gansevoort Plaza resemble female breasts with pronounced nipples.

The more substantive criticisms of Sadik-Khan’s approach suggest that even well-meaning alterations to the street can cause collateral damage. Take the newly designed Chelsea avenues. On the one hand, the mere existence of a broad, protected bike lane that swallows a lane of traffic is a minor miracle of progressive planning. But local business owners say the bike lanes have eroded their profits, preventing their customers from making quick curbside stops and forcing them to find new places to park delivery trucks. Gehl himself was initially unhappy with the design: He thought the bike lanes were too wide but was told they had to accommodate a standard-issue snowplow. And when you look at how the newly designed street gets used—the same amount of traffic in fewer lanes and a surplus of space for a fairly scant flow of cyclists—it can make even an enlightened urbanist wonder whether this was the most efficient reallocation of precious city space. It is certainly getting under the skin of some local merchants. “We’re pissed off,” the co-owner of Chelsea Florist on 22nd Street recently told the Villager.

Sadik-Khan has shown little patience for these critiques. “I think there’s a sense of ‘You don’t get it,’ ” says one former DOT employee. “It’s some bureaucrat telling us what’s best for our neighborhood,” complains Sean Sweeney, who directs the Soho Alliance, a volunteer community group that has sparred with Sadik-Khan over a Grand Street bike lane. “The DOT says, ‘Here’s where we’re going to create a bike lane, and you have two weeks’ notice.’ ”

Similar complaints were common during last year’s congestion-pricing debacle, in which Sadik-Khan played a key role. “You are either for this historic change in New York or you’re against it,” she warned Albany lawmakers, echoing remarks from the mayor. “And if you’re against it, you’re going to have a lot of explaining to do.”

It didn’t help matters that Sadik-Khan, racing up to one statehouse meeting, was pulled over and ticketed for illegal use of the car’s lights and siren. (She wasn’t driving.) The episode revealed nothing about the merits of congestion pricing but was a perfect cudgel for her critics. “As she was telling everybody else not to drive their cars, she was speeding her chauffeur-driven limousine to lobby us not to drive our cars,” says Assemblyman Jeffrey Dinowitz. “I think she’s an anti-car extremist. It’s kind of easy for Ms. Sadik-Khan to be holier than thou and tell people they have no business driving. She may live down the block from the subway station—but most people don’t.”

The chauffeured limo (it was actually a hybrid), the Manhattan subway riders—these are classic populist pressure points. But why does transportation reform have to feel so elitist? Related issues like obesity and pollution hit minorities and low-income residents hardest. Poor New Yorkers rely disproportionately on mass transit, and public space is all the more precious to those who live in cramped apartments.

Part of the problem is the movement itself. Like environmentalist groups nationwide, the city’s transportation-reform community is rooted in its affluent, white residents. (One of its main benefactors, for instance, is the financier and software developer Mark Gorton, who has spent millions funding outfits like Transportation Alternatives and Streetsblog.) Its constituents see the city differently from most New Yorkers—and they use it differently, too. The goal of making New York more pleasant to live in is the kind of goal one sets if one believes that, fundamentally, the city already works. It’s telling that battle lines get drawn between shopkeepers and cabbies on the one hand and do-gooding activists on the other. One side is always scraping to get by, the other sees the city as its laboratory and common playground.

“I’m basically the largest real-estate developer in New York City,” says Sadik-Khan.

“I think Janette is a visionary, and she brings a lot of energy and fresh ideas to her position,” says Liu, who is a candidate for city comptroller. “But that’s not necessarily her job. Her job is to do the best she can with regard to managing traffic and striking the balance between all the entities competing for street space.” When it comes to bike lanes and pedestrian malls, he adds, “there is not an overwhelming consensus for these kinds of changes. Some people are telling other people what’s good for them.”

While she must realize what’s going on, Sadik-Khan nonetheless leaves herself exposed to critics’ caricature of a cosseted elite, almost as if she’s happy to play John Kerry to Liu’s Sarah Palin. There’s her talk about cribbing ideas from faraway lands, her idealization of a European vision of comfortable living. And there’s her kinship with cultural figures like David Byrne, who designed nine whimsical bike racks for the department.

But perhaps most important, there’s her obsession with the bicycle. Even though cycling is up in the city—levels have doubled since 2000, according to the DOT—most New Yorkers see a bike as a luxury, or don’t have the space to store it, or live and work in places that do not make for a practical commute. In the longer term, a city like New York might reorganize around a more bike-friendly vision, with more dedicated lanes and better routes stretching from midtown into the boroughs. But in the meantime, the transfer of street space from cars and trucks to bikes is a shift in power, one that disproportionately benefits what could be called Bloomberg-voting New York.

Sitting in a West Village coffee shop, Sadik-Khan does her best to refute her critics. “It’s not just about, you know, elite people on fancy bikes,” she says. “That’s one of the most cost-effective ways to get around, and in tough economic times you don’t pay to get on a bike. That’s why we’re planning a much more robust bus rapid-transit network. We’re making it much easier for people to get around. I don’t think that’s elitism—I think that’s practical.”

But even supporters of Sadik-Khan’s agenda recognize that she has had a difficult timing selling it. “I think there has been a failure to explain how these projects are not elitist,” says Aaron Naparstek, editor of Streetsblog. “And the longer that’s out there, the harder it is to get projects done.” Maybe her challenge is partly a matter of style, even sexism—perhaps a gruff man in a cheap suit with the same ideas would find a better reception in Albany and among owners of ethnic family businesses. Part of the problem, though, is substance. While Sadik-Khan seems genuinely taken by the idea of bus rapid transit, she has clearly put it on the back burner—even though it would likely have practical and utilitarian appeal. But getting a new bus system going is a lot less sexy than making pop-up public spaces, or leading Bike to Work Day rides, like she did last Friday. It would take longer, cost more, and require a lot more bureaucratic tussling (with the MTA, no less). It would be a different kind of revolution—slower, more compromised, perhaps more lasting—and would probably require a different kind of revolutionary leader.

One morning earlier this spring, Sadik-Khan was standing onstage with Mayor Bloomberg and a gaggle of officials near an industrial park in Greenpoint to announce the city’s plans for its first wave of stimulus spending. It was an unglamorous scene, and while she issued her talking points like a pro, she didn’t exactly fit in—either in gritty Greenpoint or among the crowd of machine pols with whom she shared the stage. Toward the end of the press conference, a reporter diverted the subject to the city’s streets. “What’s the thinking about the Thanksgiving Day parade?” he asked. (The new Broadway will force the parade to find an alternate route down to Macy’s.) Bloomberg seemed mildly irritated. “We are changing Broadway,” the mayor responded, “which I think will make it a lot easier to get to the theater district, to get to shopping. We think it’ll be great for business, and for pedestrians, and for tourism. And it’s going to require some changes, and we’re studying them. Things change—there’s always going to be change.”

To make sure that change works, the Broadway plan is ostensibly a temporary pilot project. If the modeling is wrong and it goes awry, the chairs will be hauled off and the epoxy surface peeled away. But Sadik-Khan insists she has left little to chance. At the mayor’s request, she recorded several days’ worth of traffic patterns on the newly shrunken Broadway south of Times Square. Once Broadway closes completely, the city will conduct even more obsessive research: video monitoring, business surveys, hourly and daily traffic counts, pedestrian surveys, vehicle-classification surveys. Even critics of Sadik-Khan’s Broadway plan don’t see much chance that it will fail. One skeptic who has met with DOT officials says he came away with “a general sense that it isn’t really a pilot program, that it was a permanent change that would only be taken back if it was completely disastrous.”

If the Broadway plan does succeed, the next step (though Sadik-Khan is not talking this way publicly) will likely be to close more sections of Broadway until one day in the near future the entire boulevard has been converted to pedestrianized open space. It’s hard to characterize how dramatic a change that would be. Imagine a Manhattan with two major parks: one built in the nineteenth century as a confined space of bucolic wonder; the other refashioned in the 21st century as a long, open boulevard slicing the island on the diagonal. This would be the most striking alteration of the city’s physical landscape since the days of Robert Moses. And more than a little ironic, seeing as Moses constructed his empire of roads and highways while serving for 26 years as the city’s Parks commissioner. One wonders what he would think of a Transportation commissioner who dismantled New York’s most famous street and turned it into a park.