Earlier this month, a throng of parents and 5-year-olds stormed the limestone steps of City Hall. Tiny towheads clutched black balloons and nagging placards: WE’RE STILL WAITING! They were waiting for kindergarten seats in hallowed District 2, a middle-class magnet that sprawls from York Avenue to the Battery. The children were earnest and adorable—and, to Mayor Bloomberg’s chagrin, there were entirely too many of them.

Based on numbers from the Department of Education (DOE), District 2 is 96 percent full in aggregate, and whole neighborhoods are overrun. On the Upper East Side alone, a thousand extra children are crammed into seven elementary schools. And now hundreds of rising kindergartners had been told that there simply wasn’t room in their zoned schools for the fall: 152 on the Upper East Side, 90 in the Village, dozens more downtown—plus a hundred or so refugees from Yorkville’s P.S. 151, still needing a home after their building was condemned in 2001.

Though the squeeze seemed sudden, it wasn’t sparked by the recession; the DOE had not been swarmed by downturned private-school families. (Girded by their own deep waiting lists, private schools can’t keep up with record demand; they harvest their 2,500 or so kindergartners, boom times or bust.) In reality, the public-school squeeze was a matter of demography. As Manhattan’s post-9/11 baby boom produced more and more youngsters in recent years, schools took more kindergarten sections than they’d been designed to hold. This just happened to be the year they ran out of extra rooms. “They knew this was coming,” says Andrew Beveridge, a Queens College demographer. “But they’re acting like, ‘Oh, Jesus, this is a surprise.’ ”

With the next school year approaching, families in limbo were understandably vexed. These were middle-class—many of them upper middle class—parents who’d played by the rules; they were planners, forward thinkers, with the savvy and income to plant their flags in optimal school zones. Now they were aghast to find their children’s futures altered by some tool of chance. “That’s the ultimate act of political cowardice—put in a lottery, so that everyone’s blameless,” said Michael Beebe, a hedge-funder whose daughter was wait-listed at P.S. 234 in Tribeca, three blocks from their loft.

While some cursed the DOE, others blamed themselves. After hearing that the Village’s dual zone for P.S. 3 and P.S. 41 was over capacity, Sacha Penn, a single mother and P.S. 3 graduate, tried to enhance her lottery chances by making the larger 41 her first choice. But her game theory backfired. Only 108 families chose P.S. 3, and all were taken in. Well over 200 picked P.S. 41, which had but 138 openings. “I should have researched it better,” Penn said tearily. “I didn’t take care of my daughter. I didn’t secure her a spot.”

Starved for answers, the parents swapped rumors of where their 5-year-olds might end up: Chinatown? Brooklyn? Roosevelt Island? For the P.S. 151 left-behinds, the DOE’s worst-case scenario was a junior-high-school basement. “They’re keeping us in the dark,” fumed Glenn Hardy, a criminal-defense attorney. “Every week, we’re getting a different story.”

Even taken together, the numbers of those affected were perhaps not so compelling—unless, of course, your child was among them. But in a time of shaken moorings, the waiting lists had resonance. “Enrolling kids in kindergarten is like picking up the garbage and making the streets safe,” says Clara Hemphill, the founding editor of Insideschools.org. “It’s a basic government service that anyone expects.” When the administration fails in such a task, says Brad Hoylman, who chairs Community Board 2 in the Village, “it’s a crisis, and not only of seats. It’s a crisis of parental confidence in the system.”

The waiting lists were but one symptom of the overcrowding causing parents concern. Class size rose this year citywide, despite a $149 million state earmark to lower it. Principals have had to expropriate science labs, art studios, even libraries for needed classroom space. At P.S. 290 on East 82nd Street, according to parent leader Andy Lachman, a reading class convenes in a small bathroom—sans sink and toilet, to be fair. A year ago, a mother named Anna took a tour of crème-de-la-crème P.S. 6 off Park Avenue, alma mater to Chevy Chase and J. D. Salinger. As they passed what looked like a janitor’s closet, Anna peered inside the dim and airless space. She saw four kindergartners huddled around a single desk for small-group math: Dickens meets differentiated learning.

The picketing children at City Hall were evidence of vast demographic shifts in the city and early warning signs of what lies ahead. They were also proxies for big questions: How has the school system changed—and whom, now, is it for? What’s the more important goal—school choice or community cohesion? And how will Bloomberg sustain a middle-class presence in the system when its interests are sometimes at odds with his agenda? As the State Legislature revisits the issue of mayoral control, the waiting lists could be seen as a case study of the Bloomberg era—what works and what doesn’t.

Back in 2002, when Bloomberg won direct and unprecedented control over the city’s schools, he confronted a system that was fractured among 32 district power bases—a fair number of them dysfunctional. For too long, Bloomberg thought, the business of education had been left to amateurs. Under his reign, the DOE would be a model of corporate discipline and streamlined hierarchy, freed from the sway of special interests or the babble of debate. His chancellor, former Bertelsmann CEO and antitrust czar Joel Klein, would take hard stands for uniformity and standardization; no child would be neglected, not in the farthest reaches of town. Their goal was nothing short of “transformation.”

Lost in the system’s reinvention, however, were parent and community voices—a loss felt acutely in middle-class enclaves like District 2. Before mayoral control, this district had unparalleled independence. It was the one place in the city where parents could help imagine and create new high schools, triumphs like Millennium and Eleanor Roosevelt. Shorn of access to the honchos who could rein in a rogue principal or get a playground fixed, parents had nursed a sense of grievance long before the combustion of the moment. But the neighborhood school was the last middle-class preserve, and the idea that it couldn’t be counted on seemed the greatest insult of all.

“The chancellor’s idea of equality,” Hemphill said, in a sentiment echoed on the steps of City Hall, “is that middle-class parents should be treated with the same disdain with which poor parents have always been treated.”

Twenty or so years ago, before the dawn of Triburbia, moneyed families in Manhattan were famously small and transient, with a one-child policy that was the envy of Beijing. By the time that child reached 5, or a second was on the way, the move was almost automatic: to cut bait for more space in brownstone Brooklyn or the fabled schools of Hastings or Montclair, New Jersey. In the wake of the mid-seventies fiscal crisis and the white flight that followed, the city abandoned nearly a hundred school buildings that might have come in handy of late.

By the mid-nineties, as crime fell and District 2 schools burnished their reputations under superintendent Anthony Alvarado, parents began to linger. “You get to kindergarten and it’s, ‘Well, I guess we’re going to try it,’ ” says Rebecca Daniels, who grew up in Manhasset and now chairs the district’s Community Education Council. “Then you get to third grade and—‘We’re here, this is great.’ By then you’re in the PTA, and the next thing you know you’re fund-raising for the Little League.”

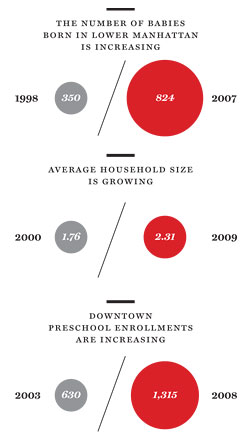

The changes were cumulative and dramatic. In a 2007 study of 2005 census data, demographer Andrew Beveridge found three transformative facts:

First, Manhattan’s under-5 set had shot up by 32 percent in five years, compared to roughly 4 percent for the population overall.

Second, most of the growth came from white toddlers, up a stunning 40 percent. They outnumbered their black and Latino peers for the first time since Lyndon Johnson ruled the White House.

Third, those 35,000 white toddlers were exceedingly fortunate. Compared with New Yorkers in general, their parents were older (mostly thirtysomethings) and better educated and with a median income of $284,208—89 percent more than the next richest group of white-toddler households, in San Francisco.

(Topping the trend off were the twins and triplets. According to Michele Farinet, the parent coordinator at P.S. 41, sixteen sets of twins entered the school’s kindergarten lottery this year.)

Growth is not spontaneous; a city must build it before they will come. When Bloomberg promised to reinvent downtown, and by extension the rest of New York, after 9/11, he stoked residential development with an array of tax breaks. Unlike the towers of old, the buildings that sprang up weren’t marketed as pieds-à-terre for Port Washington sophisticates or glam toeholds for junior execs. In a borough once synonymous with the studio apartment, the new Manhattan properties featured three and four bedrooms, plus the signature millennial amenity: the building playroom.

In 2007, the Department of Buildings issued permits for 31,918 units, a 35-year high-water mark. By the most conservative estimate, that year’s activity alone brought hundreds of millions of dollars into the city coffers in closing taxes, much of it from buyers lured by strong public schools. But a disconnect yawned between development and the children it engendered. The crux of it, says Beveridge, is revealed in PlaNYC 2030, the mayor’s blueprint for a livable city of 9 million people—who, it should be noted, will be making lots more kindergartners. The document called for parkland within ten minutes of each New Yorker and a local war on global warming, but spent less than a sentence on the DOE’s capacity needs. “School construction is not part of the plan—full stop,” Beveridge says. “They plan all the other infrastructure, but they don’t worry about the schools.”

Bloomberg had fashioned a city of cranes and baby strollers, but only the cranes fell into his field of sight. “The city booked the revenue,” says Eric Greenleaf, the chair of P.S. 234’s PTA overcrowding committee, “but it didn’t book the cost.”

The surging tide of toddlers wouldn’t have surprised anyone caught in Maclaren gridlock at Bloomingdale’s or the lines at the Bleecker Playground swings. But someone apparently forgot to tell the Department of Education and the School Construction Authority.

It was hard to fathom how Klein’s brain trust could have been so Van Winkled to the emergence of family-style Manhattan. The Buildings Department sits around the corner from the DOE’s home at the Tweed Courthouse. Both report directly to Bloomberg, who is nothing if not nimble and decisive. And yet the left hand had no truck with the right—here was mayoral control without the control.

An explanation might lie at the very hypercentralized heart of the Bloomberg-Klein regime. By gutting the “bureaucratic dinosaurs” of the community school districts and their seasoned apparatchiks, the chancellor lost his middle management in the field. There was no one to notice the sudden glut of maternity stores in the Village—or to see where a new school might be needed most or how soon. Klein’s lieutenants were like air travelers peering down at Ferraris that seemed to inch along; they were poor judges of velocity.

The DOE has no in-house demographer. Instead, it contracts with the Grier Partnership, a husband-and-wife team in Bethesda, Maryland. Eunice and George Grier “simply get the most-recent birth data,” Eunice explained to me. They consider net migration but not housing starts or up-zonings. As a result, they tend to forecast lower enrollments in development hot spots, a distortion that “leads to perpetual [school] overcrowding in these neighborhoods,” according to the city comptroller’s office. (While the School Construction Authority says it tweaks the Griers’ projections with development data from three city departments, it won’t reveal its formula.) As late as last year, the Griers foresaw a mild but steady decline in District 2’s kindergarten enrollment between 2009 and 2016. They finally smelled the Enfamil and about-faced in February, projecting a modest 6 percent hike over the same span.

Following the Griers’ lead, the DOE historically “looked for seat need based on district,” says press officer William Havemann. “We said, ‘District 3 is not using all of its space, so we don’t need to build in District 3.’ ” But districtwide figures are worthless in defining need in a given zone, which explains why so many elementary schools are bloated. While the department’s new five-year capital plan (titled “Building on Success”) claims to gauge need by neighborhood, there is still no sign of the fine-brush, zone-by-zone analyses that are de rigueur in most major school districts.

Addressing a recent meeting of the District 2 Community Education Council, Deputy Chancellor Kathleen Grimm apologized for the waiting-list chaos: “We’re sorry. We have stumbled on some of this planning.” But the DOE’s demographic oversights seem too consistent to be mere lapses. They reflect an ideology, a leadership with no great fondness for zoned schools. If you believe that the overwhelming factor for student success is some fixed absolute of “teacher quality,” then it doesn’t much matter where instruction takes place—or how many children share the classroom. It’s a hermetic, data-driven conception of the learning process, per the corporate model: You pay teachers well (salaries are up 43 percent under Klein, topping out at more than $100,000), and then hold them accountable for student progress, as gauged by the imperfect measure of state test scores. If kindergartners need to be ported five exits down the L.I.E., all that counts is the skill of the figure at the front of the room. Parental involvement, neighbors’ interdependence, a 6-year-old’s fatigue after an eight-hour day—all of these are peripheral.

“The chancellor’s idea of equality is that middle-class parents should be treated with the same disdain as poor parents.”

Those close to Klein say he is agnostic when it comes to neighborhood schools, that he views them as one of several workable modes of learning delivery. But one imagines that the zoned schools’ inefficiencies must trouble him. Because of the distortions of real estate and race, among other things, some schools become too popular and others underutilized—a waste of space.

The chancellor promotes a different model: a system of choice, where parents are consumers whose role is to pick the right product for their child. Klein has labored doggedly to enrich the system with a bigger menu: from charter schools to galaxies of small high schools to an expanded universe of gifted-and-talented programs. Some experiments thrived and others fell away, just as Klein intended. For that was how families would mold the system to their needs: by choosing what worked and voting with their feet.

School choice has much to recommend it. These options have kept many families in the system who historically might have opted out, and better served some who couldn’t afford to leave. Still, the ideal of the neighborhood school—free and open to all within its domain—remains seductive to parents. “My goodness, how marvelous to have your children around the corner and to easily walk them to school,” says Deborah Meier, a pioneer and founding principal in the small-public-schools movement in New York. “They get sick, you can hop over there. The children’s friends live nearby. The pull has to be enormous, especially if you haven’t got a nanny and all those advantages that private-school parents have.”

At the end of the day, the parents of District 2 have an embarrassment of options, save one: a guaranteed seat at a school nearby that isn’t bursting at the joists. In the DOE’s perfect universe, they fear, every school would be “of choice”—transcending proximity, unconstrained by relationships outside its doors. “What they don’t get,” Andy Lachman said, “is that parents love to bring their kids to school, they love walking to the PTA meetings, they love picking their kids up—and the kids do better, too. Joel Klein just doesn’t get it.”

From the beginning of his “Children First” initiative in 2002, Bloomberg framed his campaign for mayoral control as a civil-rights struggle, a sequel to Brown v. Board of Education. By standardizing policy—in curricula, testing, and now even kindergarten admissions—and liquidating the community school boards, he would cancel the advantages of parents with sharper elbows or shrewder navigation skills. Klein would be the mayor’s Great Equalizer, the “voice for the voiceless,” and school choice their means to bulldoze the playing field and close the racial achievement gap. In the view of one of the chancellor’s closer confidants, there is “no question that Joel talks much more about providing better choices for parents and kids in poor neighborhoods than about maintaining the quality in more-affluent neighborhoods. That’s been a much more important mission to him, as it should be.”

To a point, the mission worked, at least in some of the places some of the time. After surveying the scorched earth in East New York and the South Bronx, the chancellor flooded their zones with books and energetic young teachers. Middle schools still lagged and central Harlem stayed hopeless (except for its high-performing charters), but progress was undeniable. As Hemphill saw it, “Schools that were on the very, very bottom of the barrel moved up, from nobody knowing how to read to a third of the kids knowing how to read, and that meant something.”

But Klein was missing something on the other end of the spectrum. Not only were upper-middle-class parents sticking with public schools, but a richer city was creating a need for more schools in wealthier neighborhoods. By failing to keep up with this demand, the DOE eroded opportunity for poorer students as well. In the world of urban education, density trumps diversity. The more children per square city block, the tighter the zone and the more homogenous the school. Up until a few years ago, rich white neighborhood schools freely offered variances to families fleeing inner-city “dead zones.” But with in-zone demand swamping supply, the variance is now a relic of the past. At P.S. 199 on the Upper West Side, only 10 percent of the kindergartners were black or Latino last year; at P.S. 150, only 7 percent. Even the wealthiest Manhattan catchments include poor families, to be sure; 9 percent of the children at P.S. 6 are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. But for parents living beyond the gold coasts, Hemphill says, “school choice has pretty much evaporated.”

In some of the poorer districts in the outer boroughs, families are left with the worst of all worlds: underperforming zoned schools that have no room. The DOE perennially “caps” the enrollments of dozens of schools in the Bronx and Queens and Brooklyn, busing hundreds of kindergartners out of places like Elmhurst or Norwood. In the northwest corner of the Bronx, the poorest urban county in the nation, District 10 leads the city in capped schools—seven by the count of the DOE, nine by that of Marvin Shelton, the president of the district’s Community Education Council. (The crush can only worsen this fall, given the closure of kindergartens at city-run day-care centers: more than 3,000 of the city’s least-advantaged 5-year-olds, thrown into the DOE’s Mixmaster.) The children are bused miles east to west in rush-hour traffic and arrive home so exhausted they take two-hour naps. More than a dozen other schools dodge formal caps by shunting students to annexes blocks away or hauling makeshift “mini-schools” or double-wides onto their properties. At P.S. 46, in the Fordham-Bedford area, a hulking blue trailer was installed in the schoolyard in the late seventies. “It was supposed to be a temporary facility,” says Ronn Jordan, who graduated from the school in 1976 and now helps lead the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, “but temporary became permanent.”

When it is your child who’s affected, says Gaudy Valdez, a pocket of overcrowding feels more like a canyon. P.S. 8, in Bedford Park, is typical of these parts: 71 percent Latino, 78 percent free-lunch rate, 142 percent utilization rate. Though Valdez and her husband and their 6-year-old daughter, Hannah, live just down the block, the kindergartens are capped. So Hannah watches friends and neighbors file inside while she waits outside the door for her bus to P.S. 382, a ride of stress and daily drama. There are mornings in the cold or rain, and the bus is late, when she asks: “Can we just stay here today?” And her mother must reply: No, it isn’t your school. “We feel horrible about it,” Valdez said. Recently, P.S. 8 informed her that there might be no room for Hannah in first grade, either.

One evening in December, Eric Greenleaf entered his lobby at 150 Nassau Street and stopped short at a front-desk display. The building staff had lined the desk with holiday stockings, one for each child who lived there. “It was very cute,” said Greenleaf, a marketing professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business. “But it also gave me a chance to see just how many kids were in the building.”

From 124 occupied units, Greenleaf expected to count around 35 stockings—a number in line with the CEQR (or SEE-kwer, for City Environmental Quality Review) standard for Manhattan, allowing for a handful of private-school defections. As it turned out, the stockings numbered 51. By the time he finished his tally, the professor realized that the schools in lower Manhattan were going to be even more crowded than he had thought.

Downtown is the epicenter for Manhattan’s next wave of overcrowding, a problem that could dwarf what we’re seeing today. The downtown building boom since 9/11 has more than doubled the number of homes there between 2000 and 2008. (While construction has slumped this year, it is expected to add another 2,725 units between 2009 and 2011.) What’s more, by 2007, the proportion of downtown households with children under 18 had risen by nearly a third since 2004, to 25 percent—and four of ten childless couples said they were “very likely” or “extremely likely” to have children within three years.

At the elementary-school level, the CEQR for Manhattan is .12. In other words, the School Construction Authority would expect twelve public-school pupils from pre-K through fifth grade to be spawned by every hundred units of new development. A while ago, it occurred to Greenleaf that the ratio might be badly lagging demography in parts of Manhattan—that the borough might be edging closer to Staten Island (a CEQR of .21), if not Brooklyn (.29). With twins in second grade, the professor had a vested interest in seeing how the neighborhood’s rapid growth might play out in its schools. So he set about tracking the relationship between downtown births (as reported in the city Health Department’s vital statistics, a year after the fact) and the combined kindergarten enrollments at P.S. 234 and P.S. 89, the two zoned schools, plus P.S. 150, a small districtwide school that draws primarily from downtown.

After a post-9/11 dip in 2002, births in lower Manhattan went on a steady climb: from 565 in 2003 to a stunning 760 in 2006. Greenleaf found that somewhat more than half of these totals would be reflected in downtown’s public-school registers five years later. Last spring, he presented his findings to two overcrowding task forces, and his research became part of the parent-led campaign that spurred the city to open the Battery Park City and Spruce Street schools inside Tweed a year before their buildings were ready.

Still, the holiday stockings nagged at Greenleaf. Just before New Year’s, as the 2007 vital statistics came online, he paged down to the column for live births for the lower Manhattan community district: 824, another 8 percent higher than the year before. It was enough to confirm that the two new downtown schools would be stopgaps at best. Even assuming that all the downtown schools took in the United Federation of Teachers maximum of 25 per kindergarten classroom, Greenleaf calculated that they’d be well beyond their intake capacity by 2012. “That’s when the crunch comes,” he says.

And there is no good reason to believe that downtown’s population will stop there. Lower Manhattan is verging on 70,000 people. At a birthrate of fourteen per 1,000 (Park Slope in an off year), that translates to roughly 1,000 babies per annum—and 550 kindergartners, more or less, five years later. The five downtown schools are designed to hold only 375. The math looks inexorable.

To be sure, the DOE has a demonstrated talent for brinkmanship. It could forestall the crisis by moving the Spruce Street middle school elsewhere, or collapsing upper grades into larger sections. But the longer-term solution would be to build two additional elementary schools downtown, on top of the two incubators opening this fall. Aside from recessionary headwinds, the hitch is lead time; it typically takes five years or longer to site and open a new school in Manhattan. Which means they should have started two years ago.

John White, the DOE’s 33-year-old chief of portfolio development, has become the department’s public face and its fluent, unflappable voice. His job is to align programs and needs in a system of 1 million children, 1,200 buildings, and 130 million square feet—and, of late, to cool inflamed parents who see those needs as underserved. “I think we should frame crisis as a time when children’s well-being is endangered,” he says. “I would not characterize this as a crisis. It is a problem that we’re addressing.”

On the waiting-list front, he is banking on substantial attrition from families opting for gifted-and-talented programs or from private-school double-bookers: “Come June, these lists will be much, much smaller, if they even will exist at all.” Last week, White reported that all of the 70-odd families remaining on the Village lists would be absorbed at P.S. 3 and P.S. 41 this fall; space was freed by moving the schools’ pre-kindergartens elsewhere in the neighborhood. He also said that the P.S. 151 families had found at least a short-term home at a former parochial school on East 91st Street.

White argues that fault for the “pockets of consistent overenrollment” in District 2 belongs to the benighted days before mayoral control: “That’s the old school board’s lag, and we are living out the results.” The district is “just beginning to see the fruits” of the current administration’s more astute planning, he says, with close to 2,500 new seats coming on line by 2012. Another 3,000 or so are budgeted in “Building on Success,” which rolls out on July 1. The allotment sounds impressive, but according to Leonie Haimson of the research-and-advocacy group Class Size Matters, District 2 actually needs 9,238 new kindergarten-through-eighth-grade seats by 2012 to meet the state’s mandated class-size-reduction goals. “I think we have a disaster waiting to happen,” says Haimson. “We’re seeing the very beginning of it now, and it’s going to leave this school system in shambles.”

Manhattan borough president Scott Stringer worries about a tipping point of school overcrowding. “Parents go where the school is,” he says. “If we can’t meet that need, they leave and they don’t look back—and that’s when we lose our tax base.” But Beveridge doesn’t foresee any substantial out-migration from the city. Recessions hurt mobility: “If you can’t sell your apartment, it’s hard to move,” he noted. In fact, the financial industry’s implosion might bring more children into District 2 schools, as real estate becomes affordable for a broader spectrum of buyers. “That $2.4 million condo might look a lot better at $1.5 million—and it has three bedrooms, so then you stay and have a kid. If the housing market drops faster than the job market, then the trend [toward higher enrollments] could continue, easily.” A child-centered, more-populous Manhattan has all the signs of “a long-term demographic trend,” he says.

The bright side is that all too many cities—Cleveland, St. Louis, Washington, D.C.—have the opposite quandary, where the middle class has deserted the public schools en masse. In New York, said Dan Weisberg, the DOE’s chief labor negotiator before joining the New Teacher Project, “we take for granted that we have schools that are going to be attractive to middle-class residents.” The hold lists in District 2, he went on, are an expression of “more demand than we can meet at this point … In some ways, it’s a happy problem.”

But try telling that to the 5-year-olds still waiting for their desks—or to the ever-growing cohort of younger ones behind them.

Additional reporting by S.Jhoanna Robledo