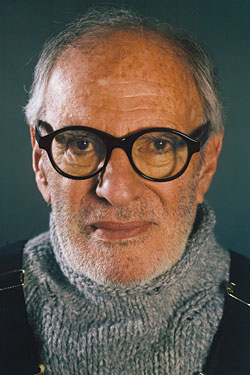

The Associated Press was at least half-right when it ran a headline, in 2001, saying Larry Kramer was dead. He was awfully close. Because he’d been sick for several years, many people who didn’t know him thought he had died already, presumably from AIDS. But AIDS, for so long his cause, was not Kramer’s problem. His long-standing HIV infection had never progressed, the virus perhaps having found that rare human host more ornery than itself.

Rather, he had end-stage liver disease, the result of a hepatitis B infection contracted decades earlier. His partner, David Webster, an architect and designer, kept him as comfortable and hopeful as possible in their Greenwich Village apartment and Connecticut country house. Still, at only 66, Kramer knew it was time to close up shop. He appointed a literary executor: Will Schwalbe, a young family friend who was then the editor-in-chief at Hyperion. Among the properties that would eventually fall under Schwalbe’s purview were plays including The Normal Heart and The Destiny of Me, the novel Faggots, the screenplay (from his Hollywood days) of Women in Love, and a raft of journalism, blog posts, op-eds, and historically important letters and e-mails. These were works that marked the world: that prompted, in a way rarely accomplished by words on paper, social action. He might have died proud of that alone.

And yet to Kramer, everything he’d been known for was just a prelude to a massive unpublished work called The American People, at which he’d labored on and off since 1978. All the plays and speeches put together would not equal it in extending his argument about the centrality of gayness in human achievement. It would also, he believed, deliver the coup de grâce to those who had for years forbidden his work entry past the polished gates of art, consigning it instead to the slum of agitprop. The American People would prove him a citizen of both neighborhoods, which were actually not even separate.

The only problem was that it wasn’t nearly done, and time was running out. “He had thousands of pages of manuscript,” recalls Schwalbe, who started working with Kramer on the material that summer, using index cards to map out the plot. “It was his legacy—and it was a mess.”

But Kramer didn’t die. On December 21, 2001, in a thirteen-hour operation, he received the liver of a 45-year-old Pittsburgh-area man who had suffered a brain embolism.

The new organ seemed to set Kramer’s clock back a few decades. His chest hair, white before it was shaved for the transplant, grew back black. The liver also seemed to recalibrate his humors, pushing his reflexive biliousness and melancholy sweetness to greater extremes. Perhaps that’s why it was possible, earlier this fall, to find him waving shyly from a leather-upholstered, artificial-flower-bedecked, horse-drawn carriage as it clopped through the streets of Dallas. Dressed in white overalls (they don’t disturb the scars the way pants do) and encrusted with turquoise (as amulets against relapse or rejection), he looked more like a retired folk singer than the gay world’s leading apostle of unrest.

He was, strangely, the honorary grand marshal of Dallas’s 2009 pride parade. Never having been so honored in New York, he was flattered. Still, after a lifetime spent in opposition, at 74 he seemed to find the perquisites of tribute both awkward and insufficient. What happened to the convertible he was promised? Was the day too hot for the horse? Would anyone listen to his speech at the end?

For he was aware that few of the 35,000 revelers along the parade route seemed to know who he was, despite a sign hastily attached to the coach and despite a three-minute biographical video that for the previous few weeks had been looping in gay bars amid the regular fare of sports, music, and porn. The video, produced by the Dallas Tavern Guild, which also produces the parade, emphasized the AIDS work that made Kramer both a hero and a lightning rod for controversy, in particular his co-founding of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982 and, when that ended badly for him, his creation of ACT UP in 1987. Arguably, these organizations were responsible, in their good-cop-bad-cop way, for bringing drugs to market that now make it possible for millions of HIV-positive people to live reasonably normal lives. As a side effect, they also instigated a fundamental shift in the way the public participates in decisions about health policy and pharmaceutical research. His former archenemy, now friend, Anthony Fauci, longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, divides American medicine broadly into two eras: “Before Larry and after Larry.” So while it was nice that Dallas named him an honorary grand marshal, putting him in the company of such luminaries as Bruce Vilanch, why has this man not been awarded a Nobel Prize?

That they don’t have a category for pains in the ass is only one reason. Amnesia is another. History may be long, but gay history has to rebuild itself from scratch every few years. Though Kramer was a biblical figure, the Jeremiah if not the Moses of the AIDS struggle, his achievements are, by the standards of a fast-forward culture, archaeological. It was 1978 when the jaw-dropping Faggots scandalized the gay bon ton. (“How dare you give away all our secrets!” the playwright Arthur Laurents supposedly complained to him at the time.) Faggots might have sunk permanently under a wave of hostility had not the first reported cases of a new disease, three years later, made the novel’s famous warning to gay men (change your ways “before you fuck yourself to death”) seem prophetic. But a prophet was not what Kramer wanted to be. That he was for too long one of the few people screaming about “the gay cancer” (and collecting money to fight it at the ferry dock in the Pines) just made him angry—and the sentiment was reciprocated. In response to his 1983 New York Native article “1,112 and Counting,” a condemnation of government inaction and gay nonchalance now acknowledged as a landmark of activist journalism, he was dismissed by his peers as a nasty prude. And in response to his mounting disappointment with what he regarded as the insufficiently militant tactics of GMHC, he left—or got kicked out the door.

But that was 26 years ago, and the articles and screeds he produced as the devastation continued were already published as a historical collection (Reports From the Holocaust) in 1994. The Normal Heart, in which a Kramer-like figure named Ned Weeks acts all Kramer-like and gets ousted from an organization like GMHC, was old enough five years ago to deserve a revival at the Public Theater. The production made for rich entertainment but could not have given a young person any sense of the degree to which the original had guilted and galvanized audiences in 1985, permanently altering New York’s—and thus the country’s—conversation about AIDS.

Well, not permanently. The attention of gay people is mostly elsewhere these days. And though a few twentyish admirers thank Kramer for teaching them, via his books, to fight, they have little else in common with him. He was never much of a youth, even in his youth. In Faggots—a Boschian nightmare of sexual excess fueled, Kramer argues, by the characters’ internalized homophobia, but more proximately by drugs and alcohol—it’s the Kramer mouthpiece, Fred Lemish, who harshes everyone’s highs. (Kramer says that despite its humor, the book was not satire but pure reporting.) Today he barely drinks, and not just because of the new liver—yet he seems to find it unremarkable, or even exciting, that his partner co-owns a leather-and-jeans bar called the Dallas Eagle. It was in fact Webster, a member of the Tavern Guild, who proposed Kramer for grand marshal, keeping the whole thing a secret so as not to disappoint Kramer should the proposal be rejected.

Webster is almost uniquely exempt from Kramer’s absolutism, perhaps because it never worked on him. Fetishized in Faggots as the beloved but untouchable Dinky Adams, Webster kept Kramer at bay even when they were lovers in the late seventies; after they broke up, they did not see each other until seventeen years later, when Kramer sought him out to design the country house in Connecticut. Now Webster takes meticulous, if not exactly doting, care of Kramer: an apple, a bottle of water, and half a sandwich were neatly prearranged in Kramer’s parade tote bag. That the two men are together after all this time—though often in different cities—is, as Kramer sees it, a validation of the virtue of persistence, though it can also be read as the opposite; his persistence may be what originally pushed them apart. In any case, nothing’s perfect: “I know I’m not the love of his life, and that hurts,” Kramer says.

Clearly, though, Webster is the love of his: “I still look at him and can’t believe he’s here. I can’t believe he puts up with the likes of crazy me.” Webster says he does so by engaging not with “the public Larry” but with the “little boy who just wants to have a friendship.” As composed as Kramer is kvetchy, Webster prefers to be the “backstage wife”—to have “my own life and not live in his spotlight. Nor he in mine.” That was evident at the parade: When Kramer reached the end of the route and backtracked to watch the tail of the event, he shouted joyfully at the Dallas Eagle float, with Webster dancing atop it. Trim and distinguished, Webster is one of the few 62-year-olds who can still pull off the bare-chested-with-leather-sash-and-armbands look. But he did not hear Kramer’s cheers.

Being heard matters terribly to Kramer now. (Listening to others is harder; he wears expensive hearing aids that sometimes get misplaced and must be protected from the curious palate of his dog, Charlie.) Temperamentally unsuited to ceding the pulpit, he has never accepted the national gay organizations as competent advocates for gay people, and, in the wake of New York’s failure to pass a same-sex-marriage law, can only repeat his contention that state-by-state incrementalism on such matters is “a waste of time.” If it depresses him, that’s because it’s personal: “I can’t afford to wait for gay marriage in ten years!” he moans. “Unless something radically changes, I won’t be able to leave my estate in any sensible way to David, and everything we built up together suddenly won’t be there to support him. That’s criminal.”

Depression wasn’t so much a problem back in the days of his AIDS activism, when he was “operating on all cylinders.” The posture of opposition cured him, if temporarily, of the anomie and drift that had defined his awful childhood (bullying father, unprotective mother) and young adulthood (he tried to commit suicide during his freshman year at Yale). After his glamorous but unfulfilling movie career (mostly spent in London) and a big flop Off Broadway in 1975, he was happy to be fully occupied with AIDS. “It was a euphoric feeling: to be useful, to not have enough hours in the day,” he says. “And I came to realize that I had been given this, like a reporter who gets parachuted behind enemy lines and gets his first big story. I was the one left alive to tell it.”

But now that there isn’t any political issue he “wants to get in on or that wants me to get in on it,” what story can he tell?

Welcome to Larry Kramer’s Third Act.

At the moment, The American People towers high on a desk that has overtaken his book-lined living room. From a simple insight, it has grown to some 4,000 pages. “Ronald Reagan kept making speeches about ‘the American people,’ ” he says, “and it totally pissed me off because his American people didn’t include me or us. So that’s the name of the book, but it’s the gay American people.”

Kramer is stingy with details, perhaps because the book beggars description: a screed that swallowed a history, or vice versa; the combination further swallowing parts of Kramer’s oeuvre (Faggots and The Normal Heart are embedded in their entirety); the whole thing framed as a tale, complete with villains, heroes, and something like a plot. Whatever it is (he grudgingly calls it a novel, for legal reasons), he believes it to be an entirely true work. Certainly it’s epic. From primordial Florida swamps to the homophilic colony at Jamestown to Lincoln’s male love and the “holocaust” of AIDS, he reframes the country as a gay creation, culminating with the advent of modern antiviral drugs: “the single greatest achievement that gay people have accomplished in history.”

If the drugs were gay people’s masterpiece, he clearly intends this book to be his. How any publisher will produce it (in several volumes? As an e-book?) is not Kramer’s immediate concern, though Schwalbe hopes they can cut about 20 percent, and polish the rest, by 2011. In any case, what interests Kramer now is getting it done while he’s still healthy, and then getting it read. It’s not an intellectual exercise. He has a messianic need to show the world, especially but not only the gay world, how much it has lost to the bowdlerizing of history. Indeed, when I ask Schwalbe what previous work the book reminds him of, he immediately says Moby-Dick: “strange, visionary, moral, questing, and also filled with fascinating and odd digressions.” Not to mention an authorial stand-in who is part all-seeing Ishmael and part maniacal Ahab.

“It’s not some suburban novel,” Schwalbe adds. “It’s a history of evil in America from the dawn of time, and I don’t mean bad upbringings but real evil: malefaction. And it’s a history of gay people from the dawn of time. The denouement is when evil attacks gay openly, in full force—and the cataclysmic effect that has.”

Though The American People includes controversial sections set in worlds and times Kramer has himself experienced, it is his “queering” of beloved historical figures that will surely get the most attention. “His idea of history is that everyone was gay: Joe Louis, De Gaulle, anybody,” jokes Kramer’s friend and Yale classmate Calvin Trillin. With Lincoln, at least, Kramer isn’t alone; recent academic studies, and articles in the popular press, have debated the nature of Lincoln’s feelings for his roommate Joshua Speed, with whom he shared a bed for four years and a loving correspondence thereafter. But Kramer says he has new evidence, including details of other male lovers, that expands on accounts that first came to light when a diary and stash of letters were supposedly found under the floorboards of a building in which Lincoln and Speed lived together. Even so, what he writes about other famous names in American history will, he advertises, prove “far more stomach-turning” to the masses.

“I do not think it is too much to state that Washington was major gay,” he says. “That the big love of his life was Hamilton, who returned that love, and that Lafayette and Washington were involved with each other romantically over many years. Others I go into include Lewis, who was desperately in love with Clark, and who committed suicide when the expedition was over and he would be with Clark no more.” He says he has “much, much better stuff” about J. Edgar Hoover than anyone has reported, as well as on FDR’s foreign-policy adviser Sumner Welles, former CIA counterintelligence chief James Jesus Angleton, and even Kramer’s old nemesis Ed Koch, who has lived in the same building as Kramer since he left Gracie Mansion, and who always denied joining the fold.

That the idea of “big queen” George amuses us—I giggled at Kramer’s phrase, and was upbraided—is itself a historical problem. However thin the proof he adduces, why should it seem silly or sacrilegious to investigate the matter? In any case, Kramer isn’t interested in proof, or facts, or the historian’s dainty calculus of context and social construction. He’s interested, ravenously, in the possibility, surely the likelihood, that at least some famous American men before 1968 had sex with other men. With their “nonstop effusive correspondence that rivals anything in Barbara Cartland,” he asks, do we imagine that none of them knew how to use their penises? In effect, Kramer is removing the quotation marks scholars have put around the flowery language of previous eras; he is turning “romantic” back into romantic and “love” back into love. When Hamilton, in a 1779 letter to his comrade John Laurens, writes that he wishes “it might be in my power, by actions rather than words, to convince you that I love you,” a sexual reading can seem unconvincing. But it’s harder to dismiss a line like this, from the same letter: “I have gratified my feelings, by lengthening out the only kind of intercourse now in my power with my friend.”

Academics may argue that the Oxford English Dictionary dates the first published use of “intercourse” in its sexual sense to 1798, but Kramer isn’t cowed by pedantry. Nor is he fazed by those who ridicule the historians on whose work many of his inferences are based. They have been marginalized, he feels, by a gay Catch-22 that casts doubt on the judgment of anyone who in seeking new understandings finds them.

Kramer can’t understand why “every gay person doesn’t agree with everything I say.”

Though he is “dying to say more” on the subject, and barely manages to stop himself before the name Andrew Jackson pops out, he doesn’t want to leave the impression that The American People is a cavalcade of presidential outings. Rather, it is an attempt to reveal history in a different light, in part by identifying gay heroes hitherto denied us. Neither the AIDS movement nor gay liberation in general created the central figure he dreamed of, around whom a cult of inevitability might form. In Faggots, a character Kramer says he based on Barry Diller is punished for failing to fill that role despite his wealth and connections and access to the tiller of popular culture. Many others have been found wanting since. Kramer himself clearly hoped to be what Malcolm X was to Martin Luther King: the scarier radical who made the more presentable figure look moderate. But since no gay Martin Luther King came along, Kramer went looking for him in the past.

It was not hard to find him, his long legs and stovepipe hat sticking out from beneath the rumpled bedclothes. But bringing gay Lincoln to life has been a trickier proposition and directly led to what Kramer calls, along with his fallout with GMHC and the “self-destruction” of ACT UP, one of his major life disappointments. It began when Kramer’s good friend Tony Kushner told him over lunch that he was working on a screenplay about Lincoln for Steven Spielberg. Kramer pounced at the opportunity: “I hope you’re going to make him gay,” he said. Kushner wasn’t sure, so Kramer followed through—for three years—with a barrage of e-mails and references and offers to set up meetings with people who might be convincing. Communications eventually broke down, with Kushner telling Kramer (as Kramer recalls): “Why must everybody agree with you?”

“How could he not have agreed?” Kramer indignantly asks. “And how could he not have used his position of power in being the writer on this script to at least promulgate the possible notion that he was gay?”

Kushner, whose blurb on the paperback edition of Faggots describes it as one of the “few books in modern gay fiction, or in modern fiction for that matter, that must be read,” remembers it differently. “Anyone who’s been in a situation like this with Larry,” he says, “and many people have, will find implausible his account of what happened, in which he’s made himself sound reasonable and interested in serious discussion. From the first moment I told him I was writing the script, he made it clear that our friendship wouldn’t survive should I fail to obey orders. It got uglier after that, or rather, Larry’s rhetoric and behavior did. Finally, this spring, I stopped responding to his e-mails.”

I ask Kramer if the way Lincoln might be portrayed in a Hollywood film was worth losing a friend over—in particular a man he used to describe as a comrade and, yes, a gay hero.

“I don’t want him as a friend if he’s going to be this kind of a person,” Kramer answers instantly. “He disappointed me mightily. He was no longer a gay hero, because he was not willing to sign on to this fight. There was enough information out there for him to create a character in which this was possible, and he was refusing to do that, and I don’t know why.”

Kramer seems genuinely mystified, but this is a man who also says he can’t understand why “every gay person doesn’t agree with everything I say—and I’m serious!” Others might argue that the requirements for a movie are not the same as those for an academic biography. That an artist gets to write what he wants. (“I don’t submit my work for political preapproval to anyone,” says Kushner.) That there are things about Lincoln more important than his being gay, if he was. But Kramer’s lifelong project has been at all costs to expand and complete the historical picture; art is not separate from politics or exempt from its exigencies. Odd that in this argument he should have turned against Kushner, of all people, who has done as much as anyone in that cause. And yet not so odd, if you interpret Kramer’s quest as an attempt to find and promote a great gay father in history since there was none in his childhood or, despite his desire to manufacture one, in his life since then. In that sense, Kushner did something far worse than refusing to toe the Kramer line: He assassinated gay Lincoln—this time, at the movies.

“I’ll be happy to discuss my thoughts about Lincoln,” says Kushner, “if and when my screenplay—not one word of which Larry has seen—is filmed. Until then, perhaps he should drop his unhealthy obsession with my writing and concentrate on his own.”

Kushner is not alone in exile from Kramer’s good opinion. Kramer and Edmund White—another co-founder of GMHC—have been sniping at each other for years. Of White’s Farewell Symphony, a sex-drenched memoir-as-novel that resembles Faggots, except that Faggots is a critique of promiscuity while White’s book reads as a giddy cook’s tour of it, Kramer wrote: “There are so many faceless, indistinguishable pieces of flesh that litter these 500 pages that reading them becomes, for any reasonably sentient human being, at first a heartless experience and finally a boring one.” Now the feud has devolved into Internet mudslinging. In a Wikinews interview, White and his partner gleefully deride Kramer as “too ugly” to have fully participated in the seventies Fire Island scene and compare him unfavorably to “real writers” who don’t spend their time “yelling in public.”

Kramer doesn’t buy that opposition, pointing to the long tradition of great literature, from Swift to Dickens to Zola, that amounts to politics by other means. Rather, he justifies outrageousness as necessary, citing Joe Papp, who had nurtured The Normal Heart at the Public Theater: “If you haven’t made somebody angry, you haven’t done your job.” But the advent of electronic yelling has changed the stakes. When Kramer is inflamed, he doesn’t just schedule a speech but zaps an e-mail to everyone on his considerable list of very powerful names. In 2008, the writer Michael Cunningham, a friend since ACT UP days, found himself publicly shamed—in just those words, “shame, Michael, shame”—by an e-mail Kramer sent, as Cunningham puts it, to “about 10,000 of his closest friends.” The crime? In its World Voices festival that year, the writers’ organization PEN, of which Cunningham was a board member, had not included enough gay panels or gay voices. (Around a dozen gay writers participated, though it was hard to count; as Michael Roberts, then PEN’s executive director, says, the work of people like Kramer has in fact made it possible for authors not to define themselves on the basis of sexual orientation.) In a return e-mail, Cunningham suggested that “public shaming” may not be “the most effective initial reaction to a disagreement with a peer,” to which Kramer (according to Cunningham) replied, “Michael, stop whining.” Things quickly devolved into what Cunningham calls “a La Brea Tar Pits fight.”

“Gay people are being persecuted in ways that make noninclusion on a panel look petty,” Cunningham says. “I’ve been to a few protests about gay people being murdered in Iran and Iraq, and I haven’t seen Larry at those. I give him his due for what he accomplished. I think he has made a real difference in the world—and abusive and slightly crazy Larry doesn’t negate heroic Larry. Probably one wouldn’t exist without the other. But he makes a fundamental mistake in abusing people who are on his side, insisting on a macho form of activism that reminds me of what I call Bad Daddy or Bad Boyfriend. Maybe he underestimates what a powerful figure he is to so many of us. Or maybe he doesn’t.”

Bad Daddy may be the template, but Calvin Trillin suggests a family dynamic that’s just as telling. Arthur Kramer, eight years older than Larry and straight, “was the single best big brother in the world,” Trillin says. “And the most tested. If there was a way to find out whether he could push Arthur away, Larry explored it”—writing about him unflatteringly in The Normal Heart, just for starters. “And no, there wasn’t a way.”

Arthur, a lawyer whose firm became a leader in pro bono gay advocacy, died in 2008. Though Kramer has no time for psychological interpretations based in family history (he asserts that his life essentially started with AIDS in 1981), his grief over the loss of his brother—and over the suicide of his best friend and AIDS ally Rodger McFarlane, in May—seems to be amplified by his inability to identify an equivalent fraternal love in the world and its institutions, which keep turning into his father instead.

Not that he ever stops looking. Despite the profound unhappiness of his student years there, no institution means more to him emotionally than Yale—his father and brother attended, and his father made it clear that he would not pass muster as a son if he didn’t get “that piece of paper with Yale on it.” Kramer has made two major attempts to underwrite gay studies (and students) there; the first was rejected in part so as not to encourage separatism on campus, while the second, eventually known as the Larry Kramer Initiative, and financed by a $1 million gift from his brother, has now joined the list of his Greatest Disappointments. What he hoped would be an ongoing center for the study of gay history ended, after five years, in 2006: the victim (Kramer maintains) of bureaucratic infighting, gender-studies gobbledygook, and “a monstrous unacceptance of what I was trying to have taught.” A university spokesman says only that “Yale produces leaders and Larry Kramer is one of them. He is a prominent alumnus, and Yale is proud to be the home of his papers.” Kramer says that being treated so shabbily by his alma mater was shattering and forced him to take antidepressants. But to judge by his 1957 senior-class portrait, in which he looks as if he has been interrupted while crying, you’d have to conclude that the shattering happened long ago, and that Yale has something to answer for, then as now.

It is not news to Kramer that he loses friends and institutions the way other people lose glasses. Sometimes he says he doesn’t care, but other times he admits it pains him deeply. “I’m complicated, what do you want?” he explains. His good name matters to him; he begs me to contact people who will say nice things about him. There is no shortage of fans, in fact. But few are unmindful of the danger of exile, especially those who have returned from it. Alison Richard, the vice-chancellor of Cambridge university, says Kramer is now her “dear friend,” though she no doubt remembers his calling her a “termagant woman” when she was Yale’s provost and stood in his way. “How we got from ‘there’ to ‘here’ is among the joyful mysteries of my life,” she wrote in an e-mail, “and I’m content to leave it that way!”

For someone so loving and sensitive, Kramer has a strangely vague sense of the effect his anger has on people. After all, in writing an autobiographical character like Ned Weeks in The Normal Heart, he would seem in some way to be acknowledging, if valorizing, his own bullying. (Kramer admits that he can see his fingerprints on what happened to him at GMHC.) Having learned at an early age to fight back loudly—his father “never spoke in anything but top volume”—he may not even hear his yelling as an expression of anger. Trillin thinks it’s usually just pump-priming, a clearing of the throat. “But the essential thing about Larry and AIDS,” he says, “is that he was right. And the theater of it had an effect. It made you think: If this normally civilized man was acting in this manner, then it really must be as bad as he says.”

But who is the enemy now? Not that old standby, the medical Establishment, which gave him a liver and thus his life. Nor his insurance company; Kramer gratefully pays almost nothing for the thousands of dollars’ worth of anti-viral and anti-rejection drugs delivered monthly to his door. As for homophobia, it may now be too diffuse to respond to the full-bore strategy of a Kramer-style attack. The “lack of anger” he finds around him, and which he has attempted in recent years to replenish from his own apparently bottomless supply, similarly cannot be attacked head on. And sitting on a sofa in his third-floor apartment (he’s terrified of heights because they invite jumping), sweet little Larry—asking after one’s health, cuddling his terrier—seems to know it. Of course one quickly remembers that even pets are made part of the struggle. A few years (and another dog) ago, when Koch moved into his building, Kramer was ordered by management to keep his distance, at least verbally. So when Kramer ran into the ex-mayor in the mailroom one day, he looked at his pooch and said, “Don’t go near him, Molly, that’s the man who murdered all of Daddy’s friends!”

The weird hilarity of the remark made it famous, but Kramer wasn’t being funny; he was being true to his principles. “He’s so in-your-face, so outrageous, so offensive in his tactics, that for all the good work he has done he has been marginalized,” says Barbara Kellerman, who teaches Kramer alongside Lincoln and Lao Tzu in a course called Leadership Literacy at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “But that doesn’t mean the tactics aren’t necessary. Leadership is a question of the person meeting the moment. His extreme leadership met that extreme moment. It is arguably less suited to a moment that appears to be about slow and steady progress. Is Larry Kramer agile enough to adjust to the needs of the moment? That’s very much an open question.”

It was Kellerman who brought Kramer word of the latest—and, in some ways, most insulting—outrage against him, this time courtesy of Harvard. In October, the university’s art museum and Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts opened “ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993,” but nowhere in the exhibit’s online guide is Kramer mentioned. Furthermore, in all the ancillary “programs, speakers, panels, readings, what-have-yous,” Kramer wrote in one of his e-mail zaps, “there is not one appearance scheduled for the person who started it all.” His anger was not assuaged by a curator for the exhibit who told him (he says) that they had decided “only to use ‘young people’ so that the Harvard kids would identify more.” “I was boiling over and wanted to say, ‘You are selfish and incompetent,’ ” he continued, “but all I could blurt out was, ‘These kids should hear me!’ ”

It’s not vanity, or not just vanity. Kramer is genuinely concerned about the fate of others, a fate in which he believes himself to be crucially involved. He therefore worries constantly about the project that failed, the friendship that cratered. Recently he’s been up nights working the e-mail list to set up (with Scott Rudin’s help) a production of A Minor Dark Age, a startling 1973 play that he thinks may revive his theatrical reputation. And when he ran into Cunningham at a holiday party, he humbly reintroduced himself: “I’m Larry Kramer.”

“I know who you are,” said Cunningham. The two men apologized and kissed.

But no matter how many e-mails Kramer circulates, or fences he mends, the danger of rejection is everywhere, inside and out. The present constantly renews its depravity. No wonder he has turned his attention to history: as a corrective but also a salve. In history heroes are treasured for their peccadilloes, not vilified for them. (Lincoln, gay or not, was a very strange, emotional man.) In writing The American People, he can write himself a context he wants to be part of instead of the context he actually lives in. He can join a bigger parade than Dallas’s, or even New York’s.

But for the moment he has come to the end of the route. The last float has floated. Thousands of revelers have collected to cruise and mingle in Dallas’s Lee Park, where Michael Doughman, the Tavern Guild’s executive director, introduces Kramer: “If you’re a young person you may never have heard this name, but he is a true American hero.” There is polite applause.

Kramer has shown me what he intends to say. He will remind the crowd how they are hated, he will criticize passivity in the face of that hatred, he will paint a picture of the glorious days in which gay people made progress because they “fought like screaming fucking banshees.” He will say gay people are smarter and make better friends than straight people, a contention that might surprise Tony Kushner, if not Lincoln. All of this will draw the usual divided response. Commenters on the Dallas Voice website will start an online shouting match afterward: “His bloated and self-righteous performance today is further proof that times have changed, and changed dramatically.” “If it wasn’t for people like us, most of the people you call friends would probably be dead now.” “I rest my case.” At least that will be better than the local television news coverage, which is next to nil, not only for Kramer but for the entire pride event.

But Kramer doesn’t yet know about any of that as he bounds surprisingly nimbly up the stairs to the dais, grabs the microphone, and stares at the crowd in front of him, like a lover who hopes his passion will be returned but from experience knows better. If he ever finishes The American People, these happy, ahistorical citizens will be his audience. “Can you hear me?” he shouts. “Are my words coming through loud and clear?”