On the morning of September 30, the lawyer Joe Heinzmann arrived at 100 Centre Street, the ominous-looking courthouse in downtown Manhattan, for a hearing. At the metal detectors, he removed his keys and iPhone. Then he heard the court officer.

Nobody in. Nobody out. Lock it down.

Steel barricades were placed in front of the doors. What was going on? Was this a drill? A massive line formed. Shortly, correction officers were combing the streets in gladiator garb—flak jackets, riot helmets, leashed dogs.

Heinzmann saw an officer he knew. “What, you guys lose another one?” Heinzmann joked.

In fact, that was what had happened, the cop told him sheepishly.

A con had escaped. The officer showed him a picture of the wanted man—it was one of his own clients, Ronald Tackmann.

“It was my guy,” Heinzmann tells me as we drive to Rikers Island. As assigned counsel, Heinzmann has represented the rainbow of criminal offenders. He’s never defended anyone like Tackmann. “Most people will go through their lives never doing something that bold that successfully,” he says. “The degree of success here is at the absolute highest level. No weapons. No violence. And out the front door of the courthouse.”

There is a kind of genius there. Tackmann is a career criminal, with multiple felony convictions, but he’s something else: an artist in several different mediums—painting, sculpture—one of which happens to be escape. And, as with any artist’s talent, the limitations and difficulties distilled and purified it. Freedom, however, seems to be too large a canvas. A day after his escape, he was recaptured. He faces trial on several robbery charges early in the new year. If convicted, he may spend the rest of his life in prison. “This is a guy who has more fun figuring out the puzzle than completing the puzzle,” Heinzmann says. “The challenge is over, so why bother with the rest? The rest is just detail.”

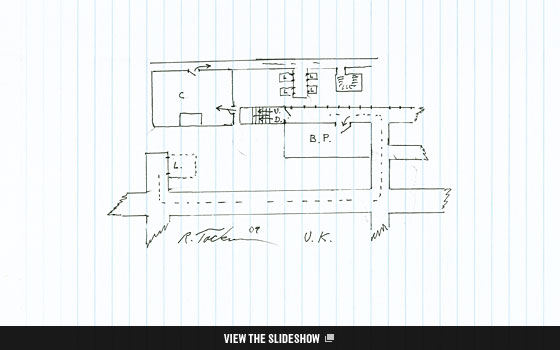

Heinzmann and I passed Rikers Island’s endless skein of rusted barbed wires and finally arrived at North Infirmary Command, where Tackmann is now being held. “This is where we keep our high-profile inmates,” a captain tells me.

We walk down gray corridors, past a glass case filled with Rikers toys—nails wrapped in string, homemade shanks, cigarette-lighter blowtorches. Up the elevator, we are led into an old hospital room. The room is as cold as a meat locker. An official from the NYC Department of Correction is here to listen in on the interview. Another correction official, who is investigating the escape, is also here. We all shiver in our suits, eager to hear: How did Tackmann do it? “Well, this move,” Tackmann says, leaning in close. “I found this move a couple of months before.”

Tackmann does not look like a prison legend. In fact, he looks ill. His skin is as white as the belly of a frog. He says he has hepatitis C, cirrhosis, diabetes, and a hernia. His hair is an unlikely shade of brown—he colors it with jailhouse coffee—and he combs it over in a Ponyboy-like pompadour. He grins. He chuckles. It doesn’t make sense. He’s looking at sixteen to life for his most recent charges, a life sentence considering he’s been denied parole every time he’s been in front of the board. So what’s so funny?

“You gotta have a sense of humor,” Tackmann says.

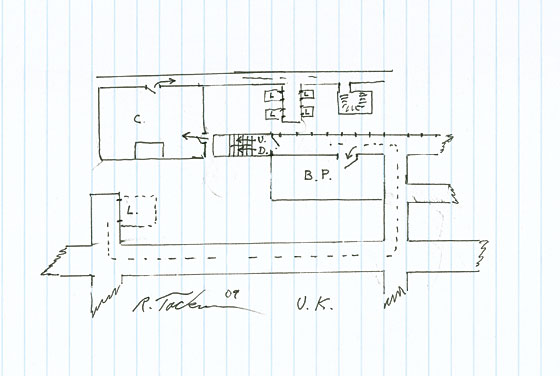

Back to the move. When he went to court for hearings, he could see the system was flawed. He would arrive on the twelfth floor in handcuffs and attached at the waist to a dozen other inmates. A correction officer would lead them into the bull pen, an area where inmates wait for their lawyers. From the bull pen, the inmates would follow their lawyers or court officials either up a set of back stairs into a courtroom or down a set of stairs.

The more Tackmann went to court, the more he noticed that once the inmate at the head of the line would get uncuffed and turn into the bull pen, he would be out of view of the correction officer at the back of the line. He could then avoid the bull pen and dart down the rear stairs.

He’d still have to get out of the building. And for the knowledge to accomplish this, he had to reach back to his hard years of criminal apprenticeship. In his upstate sojourns, Tackmann was often housed near celebrities like John Lennon’s killer, Mark Chapman (“Not a bad guy; he has a wife that looks just like Yoko Ono—that’s fucked up!”); serial killer Joel Rifkin (“He always treated me right”); and Howard “Buddy” Jacobson, the famous horse trainer convicted of murdering his model ex-girlfriend’s new lover. Jacobson escaped. He persuaded a friend to pretend to be his lawyer. In the lawyer-conference room, Jacobson’s friend removed a suit and razor from his briefcase. Jacobson changed into the suit, shaved, and walked out of prison pretending to be his own fake lawyer.

Tackmann’s ruse was hatched in the same spirit. On the morning of September 30, Tackmann prepared for court in Manhattan. He dressed in a light-gray three-piece suit that he thinks was his stepfather’s. He wore two sets of dress socks. One around his feet, the other around the Rikers Island slippers he was ordered to wear (“to make them look like shoes; they looked like suede shoes”).

As he was bussed to the courthouse, he rehearsed the move in his mind.

When you come up to the twelfth floor, you’re handcuffed with like twelve people on a chain. The C.O. is right there with you.You have to be ready, so if the move is there …

That day, the move was there. “I was in the front of the line. The C.O.—it was some new guy. He un-handcuffed us in the hallway, and I was the first one around the corner.”

Tackmann raced down the stairwell and knocked on a courtroom door. A court officer opened it.

Tackmann had the shtick worked out—the lawyer in distress. “You know,” he said, “I was just with a client, and my mother is real sick in Bellevue. Could you tell me how to get to Bellevue? I gotta get over there fast; she is 80 years old.”

He wanted to sprint. The adrenaline was gushing. He calmly walked to the courtroom entrance as the sweat trickled around his neck. He raced down several flights of stairs and tried the door. It was locked. He walked down another flight. Locked. What is going on? Did they find out I was missing already? One more flight down. The door was open. He jumped in an elevator, got out on the ground floor, and walked into the street. Freedom. But not for long.

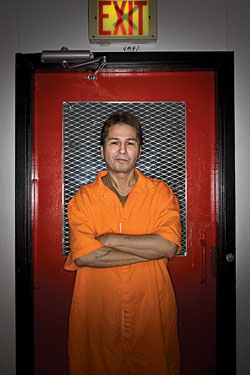

Tackmann’s rap sheet runs 24 pages long, with 57 arrests, including 27 felony charges that span the past four decades. Aside from a few incidents (like selling glue in 1969), Tackmann is a perennial stickup man. Sometimes he’d stash a toy gun in his waistband, or use a cigarette lighter shaped like a gun, or push his finger into the cloth of his jacket to simulate a weapon. His preferred targets were kid-friendly retail stores with names like Yogurt Rainbow. His crimes were crude theater, a game of dress-up. He’d walk in with a disguise, flash the fake weapon, and bark movie-sounding demands like, “You know what I want.” He was so unconvincing that sometimes his would-be victims chased him away. He was a hard-living party guy in tight jeans and half-buttoned shirts. He robbed to feed his drug habit.

“When we were doing stickups, it got to the point where it was like having a credit card,” he says. “I used to tell my partner, ‘We’re spending so much money on coke, we’d be better off having heroin habits. There’s no way we could spend this much on heroin.’ ”

He grew up in Queens with an aunt and uncle—his mother was working and his father, who was in the entertainment business, was out of the picture. Tackmann says he dropped out of school in the third grade to work on a hot-dog cart, a claim he later told me was an exaggeration. (“It was the fifth grade,” he corrected.) He was good with his hands and worked a few straight jobs, installing carpet or floor tile or aluminum siding. He even bought his own van and his own tools. But his lifestyle was more expensive than his means, and he began collecting criminal charges.

By 1985, the justice system had lost patience with him. And the feeling was mutual. The same year, facing a hefty sentence in state prison, Tackmann decided to escape for the first time. His inspiration came from statues that Hispanic inmates had carved from soap.

“I looked at them and said, ‘Didn’t John Dillinger make a gun out of soap and escape?’ So I carved out a gun.” He used black paint pilfered from his Rikers art class to paint the barrel, brown paint for the handle. He stole small screws from old clippers in the barbershop and plugged them into the soap. Another metal piece he used for the nub. He cannibalized a broken pair of eyeglasses and used part of the frame as the gun’s trigger guard. To stash it, he built a secret compartment out of cardboard. He painted it the same color as his cell wall and placed the compartment near his toilet.

Next, he conducted a test. To use the soap gun in his escape, Tackmann needed to convince himself it was real. He pulled it on an inmate to see if the appearance was menacing enough. The man’s fearful recoil told him all he needed to know. He also needed a handcuff key and was able to purchase a plastic one from inmates who got them on the black market. He then needed the courage. On a transfer upstate from Rikers, near exit 7 on the New York State Thruway, he tapped the metal nub of the soap gun against the metal screen on the Department of Correction bus.

Turn around and look. Slowly. I got a gun back here. Listen carefully. You’re going to see your wife and kids tonight. Nobody’s got to die. Driver, shut off the bus. I want you to let me out. You do anything stupid, I’m going to shoot your partner.

The guards looked at the gun. They did as Tackmann said. One guard removed his jacket and hat. Tackmann put them on. He locked the guards in the back of the bus with the other inmates and drove back to Manhattan. Over the walkie-talkies he heard reports that the bus was missing and pulled over near 118th Street, ready to run. He heard the other inmates clamoring, begging him to let them out. He opened the back door of the van to help them. Two cons, hoping to get their sentences reduced, jumped him. He was punched, tackled, and charged with his first escape attempt.

“That’s the one thing I never told anybody,” Tackmann says, recounting the story. “How did I get [the gun] on the bus? This is something you can’t stuff—you know, put it in your ass.”

I press him for the answer.

“Hey, Copperfield has tricks he don’t tell nobody, right?”

Within six months, Tackmann had made another gun. This one, at least in theory, was a significant advance. “Every time I got on a bus, the C.O.’s, they’d say, ‘Tack, you better fire a shot through the windshield next time or no one is going to believe you.’ So I thought, That’s a great idea!”

The trigger of his new weapon was a matchstick and striker. The gunpowder was graphite from pencil shavings and charcoal, and the barrels were made of aluminum from cans.

“Each barrel was tested,” Tackmann says. “But I never tested each barrel together. So when I fired the first shot, that ignited the second shot. I say, ‘Freeze, drop your guns.’ They say, ‘We ain’t dropping shit.’ ”

He ended up in Attica, where he became an obsessive gunsmith, something that did not endear him to the authorities. From a report in Attica shortly thereafter: “Officer Yavicoli came upon a package of Blend tobacco in Tackmann’s cell that didn’t feel right … Hidden in the package was a facsimile of a .25-cal. automatic pistol.” At Clinton Correctional: “Upon having the cell door opened, inmate Tackmann dove to the rear of his cell by the toilet … parts of a homemade handgun made from a bar of soap were found in the toilet.” A year later, Tackmann was disciplined for writing a letter in which he allegedly threatened to “start teaching everyone up here how to make five types of guns! And in two years this place will look like the OK Coral [sic]!”

“You know what’s faster than the speed of light?” Tackmann says. “Thought. Think about it. We can think about Mars and be there. You can travel anywhere with the mind.”

Locked down 23 hours a day, in accommodations known as the Box, he escaped into his own imagination. He was a kind of jailhouse Leonardo da Vinci. His primary medium was paint: oil, pastel, watercolor. When he didn’t have paint, he used dye from food. When he didn’t have brushes, he made them from his own hair. He also sculpted. He used soap and a homemade prison papier-mâché to craft masterpieces. (His formula: one slice of bread to four sheets of toilet paper, soak, wring, repeat—add salt if available.)

There were also countless inventions. He sketched blueprints for energy-efficient houses he might build for himself one day, and filled notebooks with esoteric instructions (“Growing Penicillium Molds”) and endless ideas for gimmicks (“Toilet Paper That Will Not Tear”) and get-rich-quick inventions: pizza on a stick, a one-man jet helicopter, a pocket-size survival tent, peanut butter and jelly in the same tube.

In the Box, Tackmann’s imagination moved in a thousand surprising directions. In notebooks, he scribbled down ideas (“How to Make a Ozone Generator”) and marginalia (“Note: the bikini first came out in Paris in 1946”). He sent some schematics (“How to Build a Kid’s Push Cart”) to a magazine called Backwoods Home that paid him a few dollars for the sketch. And to travel, he painted.

“I’ve been all around the world—in my paintings,” he says. “I could do an ocean scene, and I wouldn’t do another painting for like three weeks, just so I could put it on the shelf and go there. Hawaii. California. I never been there before. In my paintings I’m there.”

He painted the life he never had: an Indian woman on the banks of a river with a bow and arrow, or inside the Pyramids of Giza with three kittenish brunettes in G-strings. Tackmann painted them busty. He sketched their nipples hard. He painted their eyes looking at him, so he could be with them there in the Pyramids.

“You know what’s faster than the speed of light?” he says. “Thought. Think about it. We can think about Mars and be there. You can travel anywhere with the mind.”

In 2006, Tackmann was released. He hadn’t been to New York in twenty years.

“That was flipped out,” he says. “Like stepping out of a time machine. The only one in ’85 who had a cell phone was Captain Kirk.”

He pulled a life together for himself. He got a job laying flooring and got a girlfriend, Nancy Bruno. She has full lips and round cheeks, an easy smile. She didn’t know—why would he tell her?—about all of Tackmann’s years in the Box and his escapes. By the time he had won her over with his tireless charm, the way a day with him seemed to last forever—he had so many ideas, so many impulses, so many places he wanted to go—she didn’t notice that she had fallen for a failed stickup artist with a nasty cocaine habit. She herself was addicted to his personality, and when he was laying carpet she handed him his tools, just to be with him.

On a May night in 2008, Tackmann had friends over when plainclothes detectives pounded on the door late at night. The noise woke up Nancy and Tackmann’s mother, Genevieve Devine, who is 80 and has memory problems. They watched the cops put Tackmann in handcuffs and take him away. In police custody, he was questioned about the robbery of a Subway near a room he had rented in Queens and a half-dozen robberies a few blocks away from his mother’s apartment on the Upper East Side—stickups that had all of Tackmann’s signatures.

“I normally hit around First and Third avenues because I was lazy,” Tackmann allegedly told the police. “I never meant to hurt anybody … I just did it to get money for drugs.” At a Dunkin’ Donuts: “I think I got around $100. I left and went uptown (around 90th Street) to buy drugs. I think I was wearing a green camouflage hat. I was also wearing a plastic nose … I had a fake silver gun that I used, which was a cigarette lighter.” At World of Nuts Ice Cream: “I was wearing a black gangster hat with a big rim … I pointed a fake black gun at him … He told me the gun isn’t real, then he came around the counter and swung at me … We rolled out into the street, like it was an old cowboy movie. He got me in a headlock.”

Back in Rikers, Tackmann was now facing such a stiff sentence for the robberies that he couldn’t possibly plead guilty, because any plea deal would probably mean he’d die in prison. He was also sick, wondering how many years his liver had left anyway. In visits to Rikers, Nancy did as she was told. She smuggled Ronnie the slice of cheesecake he wanted, the BLT, the rolling tobacco, a match, the vitamins he said would help his liver. She hid the vitamins in her underwear and slipped them to Ronnie under the table. He squirreled them away in a compartment he fashioned in the sole of his shoe. A guard spotted her. She spent three nights at Rikers. “My heart couldn’t tell him no,” she says. She listened to him tell her to wait for him, that he would get out. She didn’t believe him. “The only way he’s getting out is in a coffin.”

But he got out, at least for a while.

On the morning of September 30, near 77th Street, his first act as a free man was stopping for a cup of coffee. He walked to his mother’s building a few blocks away, nodded to the doorman:

How you doin’? I just got out.

The doorman noticed his suit.

You look good.

Tackmann rode the gilded elevator. He knocked on his mom’s door.

What are you doing here?

I’m out. I got bailed out. But I gotta run.

He grabbed $7,000 he had stashed in his mother’s apartment and disappeared. It would have been reasonable to assume that a man with Tackmann’s criminal smarts would be on a Greyhound bus to Virginia or Florida or anywhere across state lines to get out of New York. But he went to Spanish Harlem. He purchased French fries at a White Castle, he says, and two cell phones. He then went to an apartment of a woman he knew named Candy and there met a man named Mike who lived in an apartment in Washington Heights. Mike offered his couch to Tackmann, who paid the man $100 to crash there. Tackmann stayed until early morning, when Mike’s female roommate came home from working a night shift and told him to leave.

The morning was bright. It was his birthday, he was 56, and he was free. He went to a diner and saw himself in the paper. He got nervous, paranoid. He didn’t think the escape would be big news. He thought he’d get noticed if he traveled by subway. He hailed a taxi downtown to the wholesale district, around 28th Street, to buy supplies.

That night, he went to celebrate his birthday. “Steak dinner,” he says. “With what do you call it? Onions. And mushrooms. I had some wine with it. Like two, three glasses. I was high from that.”

He hailed the M101 uptown. He rode to Washington Heights to spend the night again at Mike’s place. He stepped off near 174th Street, at Amsterdam Avenue, and saw Mike sitting on his stoop. He walked toward him and stepped into the trap. Tackmann was taken into custody at 8:49 p.m. The police had been covering the block for the past hour. They’d been tipped off.

“Somebody gave me up for my fucking birthday,” Tackmann says. “Ain’t that something?”

Police searched him at the precinct and found, according to vouchers, a red wig, a red beard, black gloves, a black stocking, a makeup brush, makeup sponges, stage makeup, nose and scar wax, three hats (blue, tan, and black), a forged passport, a blood-sugar-reading device, two fake guns, and a small bag of cocaine.

“He was such a good boy, everyone liked him, even the prison guards like him,” his mother, Genevieve Devine, says when we meet. Her apartment on East 78th Street was old-school Upper East Side and is now a collection of plastic bags: his and her stuff bundled up from a recent bedbug fumigation. Tackmann’s prison belongings—his art, his porn—are bagged up in here. I can see his paintings on the walls. She points to one drawing under glass. “He did that one when he was 2 years old.”

The painting is a mess of snakes, shaded and colored in pencil.

“He’s too damn smart,” Genevieve says. “That’s what his problem is.”

Tackmann goes to trial in Queens for the Subway robbery in early January. Then he goes to trial in Manhattan for the additional robberies. His defense is that the man captured on videotape is really his oldest son, who looks just like him (the resemblance is remarkable). But the problem Tackmann has with this defense (aside from its highly questionable parental values) is that, even on the remote chance that a sliver of it is true, it all sounds like bullshit. If Tackmann’s son did the crimes, then why did Tackmann confess to them?

Tackmann’s response here is also problematic. He says he can’t read and was forced to sign his confession by the police. Tackmann has trouble reading—his jailhouse letters to Nancy, for instance, are peppered with poor spellings (“intress,” “cair”). Still, he managed to write the letters. He’s also an extreme escape risk. “He can’t even blow his nose without asking permission,” says his lawyer Heinzmann.

With his trials looming, Tackmann is upbeat. He calls constantly. At lunch, at dinner. He wants to talk about Libya, why I should invest in gold, whether I know anyone who wants to buy his mother’s television. Recently, he invited me to the Hanukkah party at Rikers Island. The party is held at night in a gym. Through the gates of their cells, inmates howl at the female guests (“Hey, mami!”) and bark at me (“What the fuck you looking at, faggot?”) as we enter the facility.

Tackmann scans the room as Lubavitch boys sing and dance to a keyboard klezmer. In Rikers, he decided to become Jewish because he likes the kosher food and the rabbi. He declines to wear a yarmulke (“It messes up my hair”) and eyes the gefilte fish suspiciously. At other tables, inmates sit with wives whose fresh eyeliner applied in the visitor’s bathroom now washes away in tears.

Tackmann ran out of tears long ago. We talk about his next disappearing act. He’s found “five ways off the island” but “only with the help of friends, you know, missionaries.” He doesn’t even dream of escaping from prison upstate. “You need four hours to get away before they find you, and those farmers, they got guns.”

I ask Tackmann’s tablemates what they think of him.

“He’s meshuga,” says Kenneth Glassman-Blanco, who has spent three years on Rikers awaiting trial on attempted murder.

“Well done,” Ivaylo Ivanov of Bulgaria says of the escape. He’s spent the last two years on charges involving spray-painting anti-Jewish slurs and swastikas in Brooklyn Heights.

“You’re that guy! It’s an honor to meet you, man,” says Mark Inesti, charged with robbery. He had had a question for Tackmann about the lawyer ruse.

“Why didn’t you take me with you?”

Tackmann laughs. “You could have been my client.”

“You’re the greatest, man. They didn’t give you a lot of extra time on that?”

“Nope.”

“Nope?”

“Nope.”

“Why not?”

Tackmann smirks. “Because I’m going to beat ’em at trial.”

He also has a backup plan. It might not happen in Rikers, at the Hanukkah party, or upstate. But when the time comes, he will know what to do. This is his gift. “I see ways out,” he says.

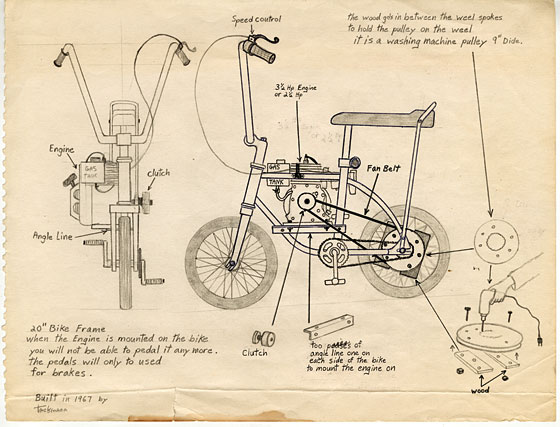

Tackmann’s Art

Tackmann makes his prison pieces from materials at hand. The inspiration for the work on this page, which he called, Before There Was Computer Games “, was the memory of going to the supermarket as a kid and begging his mother for a quarter for the ride.

Photograph by Henry Leutwyler for New York Magazine

Jet and Eagle

Oil on Paper, 1990s.

Courtesy of the Tackmann Family

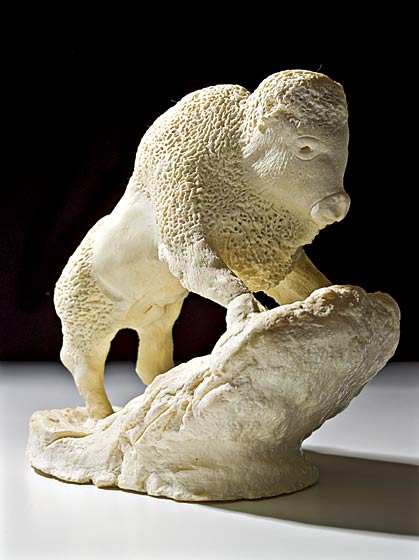

Buffalo

Prison soap over a frame of wooden pencils, date unknown.

Photograph by Henry Leutwyler for New York Magazine

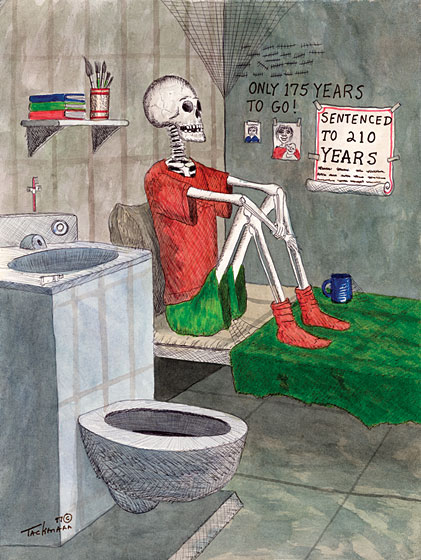

Doin’ Time

Made for serial killer Joel Rifkin, 1990s.

Courtesy of the Tackmann Family

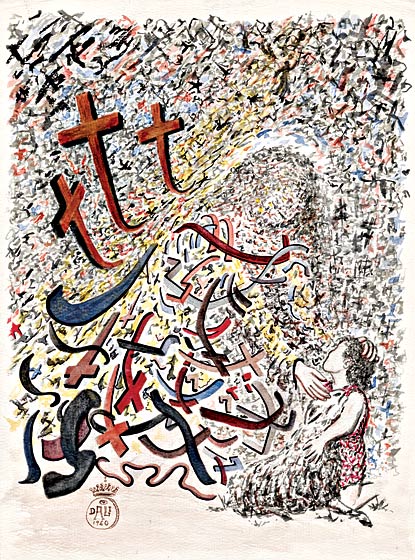

Virgin Mary

Paintings in the style of Dalí, 1990s.

Courtesy of the Tackmann Family

Tackmann’s Escape from the Courthouse at 100 Centre Street. Photograph by Henry Leutwyler for New York Magazine