The shower is a thing of beauty. Stainless-steel well point buried twenty feet below a cast-iron hand pump connected by gutter pipe to a 55-gallon drum draining through a garden hose into a propane-fueled heater hooked to an electric pump hooked to a car battery hooked to a gas generator. Flick a switch, turn a valve, and voilà: a hot shower in the woods.

Roughly three hundred feet down a rutted dirt road, in a dappled expanse of scrub pine and oak on the outskirts of Lakewood, New Jersey, about 40 men and women have made for themselves a provisional home. Dozens of tents sprawl across several acres. In addition to the shower, there is an outhouse tent with a flushable toilet pilfered from an old RV. There’s a kitchen trailer with a working range. There’s a community tent with turquoise leatherette sofas, and a washer and dryer that, when connected to the generator and filled with collected rainwater, operate as a de facto laundromat. There’s a chicken coop and a vegetable garden. There was even once a goat named Molly, passed off to a local farm because no one could stomach the taste of her milk.

The camp looks something like the scene of an extended hunting trip, but it is in fact a homeless encampment—possibly the largest in the tri-state area, not that any governmental body has bothered to keep track. Some call it Cedar Bridge, after the nearest paved road.

At night, its residents gather around campfires telling Tales of My Homelessness. Some begin with a release from jail, others with a failed business, a failed marriage, a failed drug test, or a failed ability to deal with the daily grind of a nine-to-five. Michael’s story began in New York City, where his work as a union electrician dwindled with the Dow.

“I was working with my landlord. I would send him 500 bucks, 300 bucks. Then finally I got a summons to appear in court.”

“Don’t you just love that?” asks Mary Beth, who is playing hostess tonight outside her low polyester tent.

“Three days later, I’m walking up to the apartment, I see the doorknob is different. There’s a sticker on the door: NO TRESPASSING. TENANT HAS BEEN EVICTED. Well, I managed to salvage what I wanted.”

Mary Beth nods in understanding. “I had the same thing happen, but I made sure I kept the windows unlocked, and I crawled through at night.” This was after she had been fired from Wal-Mart in what she believes to be a systematic effort to rid the company of full-time employees. “Wal-Mart sucks.” Her first night at the camp, listening to all the unknown noises of the forest, she was petrified. The next day she met Big Gerry, who had lost his house and his wife after his fitness center failed. She moved into his tent that night.

Tonight is frigid, the first unexpected cold snap of fall. Down the pathway, other fires flicker like a string of Chinese lanterns. Flashlights pass in the distance. A church group has arrived bearing large tins of pasta and salad. Tracy, who has recently assumed the role of one of the camp’s leaders, pauses in front of Big Gerry’s fire to spread the word. “There are people with food down there—kids and a lady. If anybody wants to go see what they have, now would be the time.” She perks up, remembering a bit of gossip about a new arrival to camp. “You seen the new kid yet? Wait until you see his face. He is cute as hell. He’s about 19. Tall, thin, lanky. But he has no brains!”

“Guess what he asked Mary Beth,” Big Gerry interjects. “ ‘What time do they come down here to pick up the laundry?’ ”

The absurdity of the question gets a rousing laugh out of everyone.

“I said, ‘Excuse me?’ ” Mary Beth feigns mock indignation.

“Well,” says Big Gerry, looking at her across the flame. “We’ll be out of here soon.”

They say it was once a dumping ground, but besides a few oddities found here and there—a rusted gun, a license plate from 1932—there’s no evidence of that now. The expanse is verdant and shadowed, with trees towering over a swath of land cleared of undergrowth in a long-ago forest fire. An idyllic place to set up camp.

Or so thought the Reverend Steve Brigham when he stumbled across it three years ago. He had a job with a high-voltage electrical contractor for the Port Authority—changing lightbulbs on the Bayonne Bridge—and made decent money. But since 1999, when God called upon him to help the homeless, he’s been providing the down-and-out he meets in Lakewood with provisional comfort: a tent, a sleeping bag, a propane heater.

Years ago, Steve had toyed with being homeless himself, living for long stretches of time in campers and tents and buses. Once he and his former wife drove out West to sleep on beaches and in canyons for five months. They tried to consume as little as possible, to live close to the rhythms of the land. There was a difference, of course, between the destitute homelessness he encountered through his church work and this kind of voluntary camping. But Steve related to the vagabond, meager lifestyle, and he started searching for some place better to send the Lakewood homeless community, a place where one might even choose to live. When Richie, a longtime itinerant who was living behind an industrial park, asked for help in finding a home, Steve bought a tent and started hiking through the woods. He found the clearing off Cedar Bridge Avenue, and moved Richie there in the spring of 2007.

The camp has been attracting residents ever since. A few newcomers would appear every month, and Steve responded by giving them each a plot of land. “There was no structure,” he says. “I was just eyeing out places that looked good in the area and setting people up.” By 2008 Steve realized that Cedar Bridge was becoming a permanent fixture—and a permanent home to certain residents—and that it was growing faster than any other homeless enclave in the area. He became more ambitious, reasoning that if he consolidated his efforts, he could make a sustainable, even thriving community out of Cedar Bridge. He began building a system of rudimentary services to provide the residents with rigged-up approximations of modern life. About a year ago, having quit his job to fully focus on his mission, he moved into the camp himself.

Lakewood is an easy hour’s commute from Manhattan and part of a county that, for most of the last decade, was the fastest-growing in New Jersey. The former resort town might seem to be the sort of place that would offer a soft landing, but it has been shaken hard by the recession; people there have little economic cushion, and the few social services available were not prepared for an onslaught of poverty. There are currently more than 1,000 homeless in Ocean County, but the one homeless shelter has only four beds. “They seem to think that if they don’t offer them anything, the homeless will just go away,” Steve says. Last March, there were twenty people living in Cedar Bridge; by the end of the year, the population had more than doubled.

Not that living in the woods is easy. Drinking water must still be carted in from town. Perishables quickly perish. Cell phones must be charged with a generator. A few of the residents have found employment—Darren has a job at a grocery store, and Little Jerry works at a car wash—but besides odd day jobs, most rely on Social Security, unemployment, or welfare. Getting work or a bank account or even food from a food pantry requires I.D., and those tend to disappear when you have no place for safekeeping.

Yet even a cursory survey of the tents suggests that the camp is more than just scraping by. One has a fully stocked bookshelf. Another houses a chifforobe. The neighborhood beautification award goes to Nina, the Polish lady, who has festooned her camper with exotic fans and stuffed bears, and surrounded it with planters and tiki torches. All things considered, Cedar Bridge is a rather improbable success, as much commune as way station. “I think this is the best structure that a homeless person could hope for,” Steve boasts. “It’s as good as it can get.”

The biggest issue facing the camp is heat. Last winter, Steve spent over $2,000 a month on propane, but with donations having dropped by more than half from an annual high of $50,000, he fears he can no longer afford the fuel. His solution: 16-foot-tall ventilated tepees constructed out of wooden two-by-threes, wrapped in a hide of industrial plastic, and heated by wood-burning stoves.

This idea of drawing fuel from the forest appeals to Steve, whose call to serve the homeless dovetails with a personal philosophy of social progress. “I believe we have to go back to natural renewable systems as a society,” he explains, “and I thought that implementing this with the homeless would be a nice place to start.” He refers to Cedar Bridge as a “laboratory experiment,” one in which he can test the back-to-basics, sustainable way of life he feels is not only advisable but increasingly necessary. Working with those who have dropped out of society, he envisions building a new one, harmonious and self-reliant, infused with Puritan restraint. “People have been geared to think that the path of least resistance is the ideal,” he says. “We’re trying to show them a system in a microcosm and showcase to people that it does work.” But trying to build a Utopia in a forest in New Jersey would be a daunting task for even the most committed idealists, which the residents of Cedar Bridge are decidedly not.

Steve has set few rules for the camp, understanding that people who wind up homeless are usually not good rule-followers, and that holding them to a stricter behavioral standard than even the average person, as many shelters do, can be counterproductive. He expects people not to bring drugs into the vicinity, to do their share to keep the camp tidy, and not to drink to the point of becoming a public nuisance. Otherwise, he has let the camp more or less run itself.

Over the course of its three-year existence, Cedar Bridge has experimented with almost every kind of social governance, from a band of loose alliances to a tribalist society to a pseudo-monarchy to a democracy prone to bouts of anarchy. The camp’s first self-appointed leaders, a couple called Frankie and Dragon, ruled with an iron fist. Frankie weighed close to 300 pounds and liked to be called “The Queen.” She hoarded the camp’s donations, sharing them discriminatingly. When she “programmed up” and left with Dragon in the fall of 2008, power shifted from her tent at the west end of camp to the east, where a couple named Benny and T. were gathering tents of friends around them. Benny and T. were involved in “drama,” which in camp terminology means drugs.

Steve has always hoped that the two sides of the campground, separated by a footpath, would share supplies and cooperate. But as new members arrived, they tended to gravitate to one or the other, largely along racial lines: Mexicans and whites at the west end, African-Americans at the east. Everyone but a few Puerto Ricans got along with the Mexicans, who, thanks to a language barrier, mostly kept to themselves. But between the other groups, an attitude developed that both sides describe as “the hell with everybody else.” Donations dropped off on one side tended to disappear there. If one group ran out of food or propane, it couldn’t rely on the other to provide it. Each side felt that it was being more generous than the other.

Steve had heard the grumbling around camp, but he hadn’t realized he was dealing with a full-blown coup.

This summer ushered in an era of representative government when the residents of Cedar Bridge agreed to grant control to two recent arrivals, Mike and Tracy. Mike, a construction worker and Lakewood native, was a familiar face to many, though this is his first experience with homelessness. Tracy’s is more of a chronic case, as a felony on her record has made it difficult for her to find work. An interracial couple, they plunked down their tent right in the middle of the camp and mostly put an end to the squabbling. They are a charismatic pair—he playing the cool cat to her mother hen—and their ascendancy is as close to a majority vote as Cedar Bridge is ever likely to get.

They’ve taken their roles seriously. A veteran waitress, Tracy often cooks for the camp, whether it’s hot dogs on the grill or something more elaborate, concocted from whatever happens to have been donated. (“I’m making something crazy,” she announces one night, throwing Romaine lettuce into a pan of sizzling bacon.) Mike keeps the keys to the storage tents, dispensing canned goods and toilet paper as needed. His supervision ensures that no one hoards donations or, worse, “trades them for crack,” as has been known to happen. “You have to keep a good sense of what’s going where, who’s using it,” he says.

Today a large donation of clothes has been dropped off, and Tracy has been organizing it, putting aside little piles for different people. Now she meanders through camp, peddling goods. “Men’s briefs! Brand-new! 32-34s!”

About a third of the camp’s residents are women, and, lucky for Tracy, no one is the exact same size. It’s not easy to “shop” in the dark, but once back at the donation tent, she pushes her glasses up on her nose, perches a flashlight on a defunct washing machine, and starts systematically going through trash bags.

“I don’t know about this brown shirt. I don’t think the buttons look right,” she says, placing it to the side. She holds a pair of jeans up to the light. “Hmmm … these are small. They may fit the new girl.” She starts a pile.

Not all the donated clothes are necessarily camp-appropriate, but few people expect to be there forever, and as Tracy explains, “Nicer clothes are donated than I could ever afford.” At one point, she holds out a slinky black skirt with a long slit up the back. “This is cute,” she says. “Okay, you can put a pair of high heels on, a nice cami … Burgundy shoes! Burgundy shoes would really kick that. I could wear it for Christmas.” Later she stumbles across a bag with teddies, a miniskirt, and a string bikini the size of a cocktail napkin, all of which get divvied up.

A pregnant woman named Cynthia wanders in and pounces on a stretchy denim jumpsuit (“Oh, I so want that. Oh, fuck yeah!”) before Tracy pushes a box of maternity clothes in her direction. In the box is the find of the night—a prenatal heart listener with the batteries still working—though a bag of purses also causes excitement. The women check them for forgotten cash before Cynthia selects a snakeskin clutch for her growing pile. How is she going to get all this to fit in her tent, she wonders.

Tracy laughs and shakes her head. “Nobody’s going to be allowed to go shopping with me anymore.”

At the end of October, the cold eases into a perfect Indian summer. The residents of Cedar Bridge mill around the picnic tables in T-shirts, grilling hamburgers, playing cards. It’s easy to forget that any day now, winter will be bearing down.

That thought has not escaped Tracy. Unlike Steve, she has no interest in sticking around Cedar Bridge any longer than necessary. Her criminal record makes it difficult to qualify for subsidized housing, and though she’s put in applications, she still can’t manage to get a job. Without a job, her prospects for getting an apartment are dim. Without an apartment, she can’t get an address, which she needs in order to receive a loan to attend beauty school. Mike has passed the drug test at Wal-Mart and is waiting on the background check, which he’s sure he will pass, but it’s been a few weeks since he’s heard anything. Tracy doesn’t want to spend the holidays in a tent, but she consoles herself by telling Mike that at least here she feels needed.

A lot has been happening at the camp. Three of the Mexicans disappeared, and everyone fears that they were picked up by Immigration. An older man named Aaron had to go to the hospital in the middle of the night because of fluid around his heart. Another pregnant couple moved in. Petey, one of the remaining Mexicans, learned that his mother had died, and so the camp pooled its money to help him get a rush passport and transportation back to Puebla for the funeral. The camp’s two Frankies, normally friendly and mild-mannered guys, caused a scene when Little Frankie made a pass at Big Frankie’s wife, Zenayda, at which point Big Frankie smashed him over the head with a half-empty beer bottle, leading to a trip to the emergency room and fifteen stitches. Cynthia asked Tracy to be the surrogate grandmother of her baby. Cynthia then fought with her boyfriend, Ellwood, and ran away for the night, threatening to have the baby aborted. And, in order to get away from Big Frankie, Little Frankie was the first of the residents to move into one of Steve’s sustainable tepees, which everyone else has decided is not worth the bother.

But the event that threatens most to destabilize the camp begins with a call to Steve late one afternoon. A woman from El Salvador had been fired from her job as a live-in maid when her employer became frustrated with her level of English. She has no papers, nowhere to go—and she has a 9-year-old son.

The residents of Cedar Bridge have often clashed with Steve on whether to accept newcomers, worried that his open-border policy will strain resources and cause problems in town. Technically speaking, Steve is no longer supposed to bring new people to the camp. The township recognizes Cedar Bridge to the extent that it collects its garbage, but the mayor has made it clear that he does not want the camp to grow. This is a compromise that Steve has often breached. “If somebody comes to me and doesn’t have a place to go, I’m going to give them a tent,” he says.

Rumors have been circulating through camp all fall that Lakewood will shut down—maybe even bulldoze—Cedar Bridge, making Steve’s willingness to accept a child seem almost careless. Mike speaks to him on behalf of the camp.

“For the most part, I think that’s pushing the limit. The first time you get a child down here, they’re gonna want to know how that child’s going to school, does that child have shots. If DYFS”—the New Jersey Division of Youth and Family Services—“comes down here with the sheriff’s department, you can hang this place up.”

“If we say we exhausted our options …” Steve says. “The only option this woman had was to be here.”

“No, no, no, Steve.”

“I’m not gonna have somebody wander the streets out there.”

“Okay, well, you know something? All you have to do is make that step and it’ll be your last with this.”

Just after dark, a van pulls up to the access road, and a small woman and a tiny boy get out. Steve leads them down to the Mexican part of camp, hoping that someone can translate his message that they have a place at Cedar Bridge if they want it. The mother seems mostly concerned about whether Immigration ever visits the camp. The boy wants to know if he can still go to the same school. He looks around at the tents nervously. Everyone stares at him. Now that he is here, it is obvious even to Steve how out of place a child would be at Cedar Bridge.

Steve says he will make some calls to find someone else who needs a live-in. For tonight, they are invited to stay with the woman who found them and first contacted Steve, and who now stands wringing her hands and apologizing that she can’t take them in for good. “My grandkids live with me,” she says, “and they just don’t understand poverty. All they understand is video games.” On the walk back to the van, the woman and child are silent. Steve’s flashlight catches the looming outlines of the tepees. As the boy passes, campers peer from their tents, thankful to see him go.

By Thanksgiving, mutiny is mounting. The child’s visit has spooked everyone, not least because it demonstrated just how impossible it is for Steve to say no. Plus, Steve has begun inserting himself into the day-to-day operations of the camp, and his growing involvement is viewed as a form of babysitting. He recently moved into a tepee, as if to show everyone else how it’s done. But no one wants to be forced to move, and Steve’s appeal to sustainability means little to those who see their stay at Cedar Bridge as temporary, and who bristle at the prospect of a winter spent chopping wood. His tours of the camp are bringing in donations, but everyone’s a little weary of being part of the dog-and-pony show, and many believe Steve would be able to afford propane if he didn’t share the money donated to Cedar Bridge with other homeless encampments. When the camp receives a large shipment of Thanksgiving turkeys and Steve delivers some of them elsewhere, protests are made. When he takes away the generator the following week as punishment for the trash left lying about, indignation rises. Without a generator, the residents complain, there’s no hot water. No one can shower for three days.

In the weeks after Thanksgiving, Tracy and Mike, realizing that Steve is not about to renege on the propane issue or any others, hatch a plan to take control of Cedar Bridge by aligning themselves with the township. Along with a couple recruits from camp, they arrange a covert meeting with Lakewood’s Fair Housing officer, who agrees that Mike should assume Steve’s role as the Cedar Bridge representative in town. Mike says he thinks he’s found someone willing to supply the camp with propane, and together the group starts hashing out ways to circumvent Steve’s authority. As evening approaches, Mike and Tracy return to camp, heady with the scent of revolution. Tracy pops open a beer can as if it were a bottle of bubbly, ticking off the things that have been discussed. “We’re getting our own website for donations, they’re gonna set up a bank account that’s administered by a panel, we’re talking about taking the tepees down, they’re going to make sure that we have enough propane so everybody has heat, we’re going to restructure some of the places so they’re winterized, maybe get the tarps we need to keep the snow off—Steve’s not doing any of that.”

“He doesn’t want to do it,” Mary Beth interjects.

“No,” Tracy agrees. “He refuses. He just keeps bringing new people. He’ll bring anybody down here and they can stay here forever, but he won’t help them get a job. He doesn’t want people to leave.”

“We can’t have people in the woods for the rest of their lives,” says Mike.

Tracy nods. “Now we’re ultimately accountable, not Steve. If somebody brings new people into this camp, we need to know about it. As a collective community, we will decide to let people in and out.”

“It’s gotta come through me,” says Mike.

“We make the decisions,” Big Gerry agrees. “You know what? We’ll sit down with a pad and whatever and write our shit down, our notes.”

“I gotta start giving out different jobs to different people,” says Mike.

“Oh, you know I’m right there—where are the cigarettes?”

Mike remains pensive. “Let me tell you something. It’s a lot to take on, if you’re not sure that you can handle it. I mean, me? I know I can. All y’all got to do is help me.”

“Right,” Tracy says. “And we need to make it work.”

Mary Beth raises her can. “We’re trying to make it—”

“A functional community!” Big Gerry exclaims.

“A family community!”

“Like … a rural subdivision.”

“We should get a ledger sheet from Staples.”

“Well, we can do that.”

“Yeah! Let’s get a ledger sheet.”

“First of all, we have to get a system going, and once we get the system going, then we stick with it.”

“That’s that.”

“We’re gonna be responsible for ourselves.”

“Can I have a cigarette?”

“No.”

“You have to lead by example.”

“We’re going to take what we want. We’re going to make the system work for us for a change.”

“We gotta do something.”

“Right.”

“This is a stepping-stone.”

“This is a long time coming.”

“Can I have a cigarette?”

Two weeks before Christmas, the conflict at Cedar Bridge comes to a head. Mike’s plan to receive a private donation of propane has moved forward, and his benefactor, a local contractor named Bob, arrives one afternoon to pick up the tanks for refueling. This takes Steve by surprise. He had heard the grumbling around camp, of course, but he hadn’t realized he was dealing with a full-blown coup. The propane will thwart, or at the very least delay, his plan to move the residents into tepees. Don’t they understand that he’s looking out for the camp’s long-term interest?

When Mike and Bob return from the gas station carrying full twenty-pound tanks, Steve confronts them. The tanks are his property, he says. Who will take responsibility if one explodes? But Mike is firm in his belief that Steve is denying Cedar Bridge the fuel it needs to survive the winter. When Bob chains the tanks together and gives Mike the key, Steve calls the police. The standoff comes to an uneasy resolution. “I just put my cable and lock on top of his chain and lock, and now it takes two keys to open the propane tanks,” says Steve.

Three days into this shaky détente, a blizzard hits the East Coast, dropping close to two feet of snow on Cedar Bridge—the worst storm anyone can remember spending outdoors. Half the camp evacuates, going to sleep in church basements or motel rooms, waiting out the worst of it. Those who remain round up brooms to sweep the roofs of their tents throughout the night. Most eventually give up, falling asleep in the community tent, where one side begins to buckle under the accumulation despite efforts to bolster it with wooden poles. By morning, most of the tents have collapsed, their sunken shapes hardly discernable from snowdrifts.

Tracy hides out in her tent, wearing long johns and reading a paperback romance under the covers of her cot. She’s resentful of the fact that she worked to save tents longer than their owners did and, in the end, struggled to save her own. “I didn’t have to be here,” she fumes. “I could have been in a fucking motel.” Her voice turns plaintive. “But there are a lot of people here, and what were they going to come back to?”

Steve rode out the blizzard much better in his tepee. “I lit the fire, got it warm, and then I crawled in and I was fine,” he says. In fact, all of his tepees have withstood the storm. In the community tent, there’s talk of moving into them once the snow melts—many tent poles have snapped, leaving some residents with no choice. But despite this partial vindication, Steve remains distracted and deflated.

As night falls, he drives to a Spanish-speaking church to search for several of the Mexicans who had abandoned camp during the storm. In the car, he mulls over Mike’s attempted coup. “He’s looking for the easy way. Most of the homeless are. I was just hoping they would be more sympathetic to my standings. Sometimes I wish they’d be a little more grateful.” He stares at the rutted white arc of road illuminated before him. “They don’t see it, you know,” he finally says quietly. “They don’t see it.”

When he arrives at the church, the Mexicans are no longer there. No one knows where they’ve gone, or if they’ll return to Cedar Bridge. For tonight at least, they’re choosing another brand of homelessness.

The Reverend Steve Brigham, the founder of Cedar Bridge. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

A 9-year-old and his mother arrive at Cedar Bridge. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Mike, one of the camp’s leaders, inside the community tent. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Charles, in a plume of burning garbage. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Sharon, in her tent. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Tracy, one of the camp’s leaders, preparing dinner. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

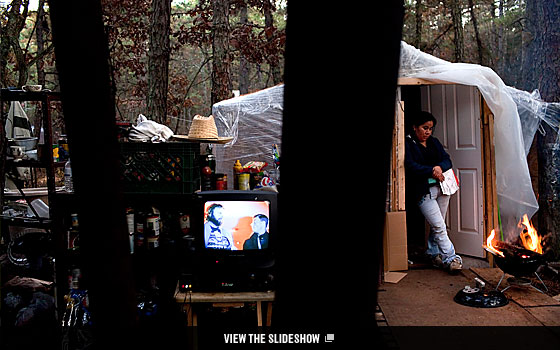

Zenayda, a Cedar Bridge resident, cooking as neighbors watch Bloodsport. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Cedar Bridge residents gather in a makeshift heated lounge. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Cheryl, outside the bathroom. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Tracy, one of the camp’s leaders, walks toward the kitchen trailer to prepare early-morning coffee for the Cedar Bridge residents. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

A homeless resident walks down a stretch of unpaved road that leads to the Cedar Bridge campgrounds. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Big Frankie cuts firewood at the west end of camp. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Charles, outside his tent. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Little Jerry lights a cardboard beer box as kindling wood. Chris and Little Jerry scrapped the trailer hoping to sell the parts for $600. They got $30. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Brian staples plastic sheeting into wooden planks to construct the camp’s tepees. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Nina smokes a cigarette in front of her decorated camp trailer. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Tracy cries in the kitchen trailer after being yelled at by a former member of Cedar Bridge over the issue of the pantry-tent lock. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Mike, Tracy, and Big Gerry eat leftover breakfast food donated by a charity group. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

KC sports his new “pimp” hat he found in a clothing donation received that day. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Chris, Little Jerry, and Mike serve themselves chicken soup from the kitchen trailer. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Most of the men in the west end of Cedar Bridge watch Bloodsport on a TV hooked up to a generator as Big Frankie’s wife, Zenayda, cooks dinner. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Zenayda poses with a stuffed animal while cooking dinner. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Chris, Mike, Big Gerry, and Little Jerry relax in their newly constructed lounge made from torn-down tepees. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Mike peeks in, while Little Jerry keeps warm inside the heated lounge tent. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Nina uses a bonfire to cook her food. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

A tent lit by its wood-burning stove. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Chris and Little Jerry share a cigarette in the heated lounge tent. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Angel tries to sleep in the noisy community tent. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Chris and Little Jerry walk from the homeless encampment toward a Lakewood city street filled with traffic. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network

Cedar Bridge in late fall.Scroll to explore the panorama. Photo: Benjamin Lowy/VII Network