E ven the saddest marriage can begin in perfect happiness. “I know it sounds strange,” Patricia Cohen tells me, “but back then we had a lot in common.” Patricia met her future husband, Steven A. Cohen, who would later be the founder and driving force of the $12 billion hedge fund SAC Capital Advisors and one of the richest men in the world, on a rainy summer evening in 1979. “It was coming down in torrents,” Patricia says, and so she ducked into a restaurant on the Upper East Side. Steve, bold even then, approached her at the bar. Patricia sized him up, and he wasn’t her type. He was a middle-class kid from Great Neck in a decent suit that, she still recalls, didn’t match his brown shoes. He was pleasant-enough-looking, in a Sears-catalogue way: short, with dark hair, a square jaw, big glasses over watery blue eyes, and a trim waist. He proudly told her that at 22, he was already a trader on Wall Street, an achievement that didn’t mean much to her. Patricia, four years his senior, was a working-class girl from Washington Heights who’d transformed herself into a sophisticated West Village woman. She wore a white camisole and a pale, rain-soaked silk skirt that stuck to her lovely legs. She worked at a publishing company, held fervent opinions about literature and theater, toyed with writing a screenplay, and usually dated writers.

Still, the eager junior trader grabbed her attention. “Steve was incredibly sweet,” she says. He wanted to impress her without quite knowing how, and it was endearing. “He just kind of was himself,” she says. They started dating three days later, and in six months they were married. They talked excitedly about how much they wanted a family, and thirteen months after the wedding their first child arrived.

But that was a very long time ago. Patricia, her lawyer, and I are in a restaurant near Lincoln Center on a bleak winter afternoon when she abruptly stops her story. Then I notice: She is crying. “He’s a bully,” Patricia manages. “I’ve been punished for twenty years,” since they divorced. “I just will never understand his anger, the turning on me. It’s really, really, really crazy. It’s so painful to me.”

In December, Patricia took a step toward dealing with her own considerable anger: She filed suit against her former husband, who is now worth $6.4 billion. Patricia demanded $300 million, accusing him of fraud under racketeering statutes—the suit was withdrawn after Patricia changed attorneys, but her new lawyer, Gaytri Kachroo, says she will soon refile. Patricia charged that at the time of their divorce, in 1990, Steve cheated her by hiding assets. But her suit didn’t merely seek financial redress; it was also a stinging personal attack, portraying Steve as not only cheap and deceitful but shady and secretive, a person who 25 years ago might have tried to evade taxes and trade on insider information, suggestions superfluous to the suit’s central claims but which nonetheless made headlines, and at a delicate moment. Steve’s company has been mentioned in connection with stock-manipulation probes, including one by the FBI. Patricia’s suit had affected Steve’s business at a time when he was trying to recruit new investors, no doubt a satisfaction in and of itself. “He’s in the most vulnerable position he’s ever been in,” Patricia wrote in an e-mail shortly before her suit was finalized.

For Patricia, pursuing her ex-husband is a catharsis long in coming. She wants her due—justice is her word for it. But there’s also obsession here, and maybe a kind of madness. For Patricia, the past is present, and now at last she can engage her long-held grievances on a big and public stage. “I’m so excited I can hardly contain myself,” she wrote gleefully in an e-mail as the suit was filed.

Patricia sometimes talks as if she were afraid of a man as powerful as Steve, certain that he has spies and allies everywhere. And yet at other moments, she’s sure she has the advantage. “Having been married to him I know what he’s made of and it’s not much; he’s a coward,” she wrote. “The twisted man is at heart a wimp.”

Whatever he’s made of, Steve Cohen is one of the great money managers of his time, moving markets, mauling giant companies, and returning about 30 percent on average to investors, after subtracting some of the highest fees in the business. He’s got a world-class art collection—Picasso and Cézanne, Koons and de Kooning, spread around his 32,000-square-foot mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, where he now lives with his second wife. He gives away millions—just last week, North Shore–Long Island Jewish hospital network announced it had named a children’s medical center after Steve and his second wife, Alexandra, following their $50 million gift—and still cultivates a “regular guy” persona, eating hamburgers at the local diner, showing up at sporting events for his and his new wife’s five kids. It’s a blessed life, with one large exception. Her name is Patricia. “She’s a terrorist,” Steve told a friend, “on a mission to make my life a living hell.”

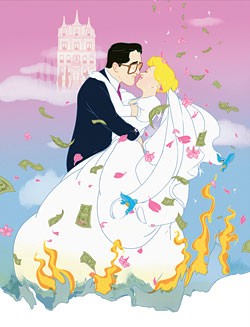

Illustration by Marcos Chin

Steven A. Cohen was born to be a trader. His father worked in the garment industry, while his forceful, stern mother taught piano 60 hours a week—though Steve notes that none of the eight children can play. Steve got more than his share of attention—he was a star student and athlete—but he craved more. “You’d do better in a family of two kids,” said his mother, also named Patricia.

In his parents’ household, money was tight and earning it much valued. “Money makes the monkey jump,” his mother liked to say. And Steve had a gift. In high school, he took a summer job at a clothing store just to be near a brokerage. “So I could run in and watch the tape during my lunch hour,” he told author Jack Schwager. The tape recorded the minute-by-minute changes in stock prices, and Steve could read it like a textbook. “In those days, [if you watched the tape] you could see volume coming into a stock and get the sense that it was going higher,” he told Schwager. Another summer, his job was playing poker late into the night, which he credits with teaching him how to take risks. He learned quickly. His younger brother Donald remembers seeing wads of $100 bills spread on his desk in the morning. Right out of Wharton, where he was an undergrad, Steve was hired as a trader, and was soon affiliated with Gruntal & Co.

In the go-go eighties, Patricia and Steve led what looked like a dream life. Money seemed to flow to Steve by some law of nature, and they liked to spend it. They traveled first class, and had a 5,500-square-foot apartment on East End Avenue, one among several homes. Steve liked Patricia to look great, an interest she shared. “I could buy as much clothing as I liked, as much as $50,000 in one month,” she later wrote.

Patricia stayed home tending the family and decorating their homes, partly from thrift stores—even then, she says, Steve had a miserly streak. Certainly, Patricia appreciated the lavish side of their lifestyle. But the job that supported it caused her problems. Trading is taxing work, and Steve internalized the stress. His moods would swing up and down with the Dow. “He used to come home beat-up, impatient, at the end of his wits,” Patricia says, and then take it out on her. “He could be demanding, hypercritical, and a screamer; if he had a bad day, he’d explode.”

In Steve’s view, it would have helped if Patricia sympathized with the strain on him. Instead, she seemed put out, as if his working so hard was self-centered. Steve understood how the market affected him; after the relationship collapsed, he went on Prozac for a time. But he could have used a little appreciation—after all, he was “going to war,” as he referred to his job, for her and their two children. But after work she’d meet him at the subway exit with the kids, as if to say, Okay, your fun time is over. As Steve experienced it, she didn’t want him to be happy.

Patricia comes from a fractured family, and she has her own ideas of the good life. She issued dramatic, “evangelical” speeches urging Steve to remember the simpler, family-centered pleasures, like trips to Disneyland or splashing in the pool with his children. She pressed him to change. Somehow she’d missed a fundamental element of Steve’s character—she hadn’t realized how ambitious he was. “Maybe I mistook his youth for idealism.”

By 1988, things were almost over—though, of course, they weren’t. Patricia insisted on divorce, but Steve beat her to the punch, serving her with papers charging that she’d abandoned him and refused to have sex. At first Steve moved out, but then, partly on his attorney’s advice, he returned to their sprawling apartment, with the kind of explanation that would echo for the next two decades. “I had every right to do so,” he wrote in an affidavit. “I paid all the expenses.” Their romance had turned into its mirror image. Steve now took some pleasure in Patricia’s discomfort, though she pushed his buttons, too. As he wrote, “She well knows how to do [that].” There’d even been a fight; Steve hit her, she says. “The one physical confrontation we had during this entire period was provoked by [Patricia],” Steve wrote. “Although she called the police, it was not necessary that she do so.” And yet even as they were divorcing, their connection was intense. They continued to talk on the phone for hours at a time, and even sometimes slept with each other. Neither one could get away.

Illustration by Marcos Chin

Finally, in 1990, the divorce was finalized, a milestone that solved little. Each stuck to his or her own version. Patricia believes he lost his way, strayed from their vows, forgot about his family. “There was something else that was more important to him.”

“What is that?” I ask.

“Well, he’s very rich,” she says.

As Patricia saw it, he loved his money more than her.

The divorce was a disaster, too. Steve gave Patricia $1 million in cash and their East End Avenue apartment, which he considered more than fair. He’d first declared his net worth at $16.9 million, according to a July 1, 1988, disclosure. Later, he wrote off $8.75 million of that as a bad real-estate investment—one focus of Patricia’s lawsuit—and recalculated his worth at $8.2 million. Thus, he later wrote, Patricia got more than half, a figure arrived at by valuing their East End apartment at $3.8 million.

As for monthly support, he first agreed to $3,730 for the kids and household costs (plus he paid for camp and school and other expenses). All told, in 1990, he spent $125,619.30 on Patricia and the children. It’s a measly sum compared to his income—$4.3 million in 1989, according to a copy of his income-tax statement, and nearly $12 million the year before. But Steve thought that he had more than met his obligation. He wasn’t required, and he certainly wouldn’t volunteer, to pay for “spousal maintenance.” He suggested Patricia get a job, perhaps as a general contractor, for which she’d shown an aptitude in selling their seven other properties. Or maybe she should write that script she’d talked about.

In 1991, just a year after the divorce judgment, Patricia returned to court. She was broke. The real-estate market had followed the stock market into collapse, and she hadn’t been able to sell the East Side apartment. “[Steve’s ex-]wife and children are on the verge of being put out on the street because his wife … is virtually penniless,” her lawyer wrote. Patricia clearly hadn’t managed her money optimally. Her own lawyer seemed to commiserate with Steve. “I readily concede that she needs guidance [with money],” he wrote. (There was an $80,000 bill from Bergdorf.)

Steve’s response to the mother of his children was, essentially, tough luck. She’d made her deal, let her live by it. That she was back in court so soon was “chutzpah,” Steve wrote. He even found fault with a $50,000 gift she’d made to her mother. “If she is in as bad financial shape as she claims she should get this money back from her mother,” he wrote.

The family they’d both once wanted was caught between them. Steve worked at being a decent father, though it was sometimes a challenge. Patricia complained to the judge that one afternoon Steve left the kids, then 10 and 5, to watch TV in his apartment while he headed to the gym. “The health club [was] located in my building [and I went] for an hour or so,” he wrote, arguing that it was all part of “a pathetic vindictive attempt” to alienate his children from him.

And to Steve, she seemed to be succeeding. As a 10-year-old, their daughter complained to him that he didn’t “give her mother enough money.” “She is fighting her mother’s battles,” Steve wrote later.

The affidavits read like a screaming match, but, the anger temporarily spent, Steve and Patricia managed to negotiate a settlement. Steve made several accommodations and in 1992 raised his monthly contribution to $10,400. In 1996, it climbed to $16,000, and from 2000 through 2003, he paid $18,000 per month in child support, which is tax-free to her, plus school tuition and “extraordinary” expenses. (In 2004, as the younger went to college, he reduced the payment to $9,000.)

It was, in Steve’s universe, not a lot of money. But he felt it represented an instance of generosity, and it exasperated him that he couldn’t get an occasional thank-you and some respect. Deep down, he viewed himself as “a softy” and not cheap, as he told one friend, and he couldn’t understand why Patricia wouldn’t see him that way.

In 2000, he even insisted on moving Patricia and her kids into a bigger place, but that became yet another case study in family dysfunction. Steve was renovating his Greenwich mansion and thought it was time to also improve his children’s living conditions—the son’s bedroom was a converted dining room. He got Patricia a 2,340-square-foot three-bedroom on Central Park West, renovated it for her, whatever she wanted. But Patricia had to move out during the renovation, and she felt evicted. To add to her sense of injury, Steve and his new wife, Alexandra, whom he married in 1992, kept the title in their name, giving her a $1,471.49-a-month lease in perpetuity. In Steve’s mind, it was for her own good. That at least kept her from mortgaging the place and running through the money and ending up homeless. In Patricia’s eyes, it also kept her subservient, a vassal of the wealthy lord, where once they’d been equals. His so-called generosity enraged her.

Illustration by Marcos Chin

Steve is a long way from the Sears-catalogue junior trader. He’s 53, soft-chinned and paunchy. He’s been bald for years, and what’s left is closely cropped and gray. He runs a huge investing business now, and is aggressively growing it; he can’t think of anything he’d rather do in life. Steve is a demanding boss, overseeing 300 managers, traders, and analysts, all of whom know the guiding principle. At SAC it’s “down and out”: Lose money and you’re gone. For years, Steve liked to sit at the head of a large table, a video camera broadcasting his every move and comment to his traders, each of the master’s gestures important. His own trades account for some 10 percent of the company’s profits. He likes to jump in and out of short-term bets, a game that keeps his interest up. He’s mellower now. The market no longer beats him up emotionally—he can even lose $100 million of his personal money, as he did one day not long ago, and shake it off.

His vast fortune insulates him, no doubt, but Steve cites another reason for his equilibrium. “I have a wonderful wife,” he says. In 1991, Steve met Alexandra Garcia through a dating service—she was the only one of twenty women who responded to his invitation. “She’d always wanted to marry a millionaire,” a friend told BusinessWeek, though she also saw Steve’s other charms. She thought he was the funniest person she’d ever met. (Steve took note: Patricia had found his sense of humor stupid.) Alex didn’t want to change Steve; she wanted to be with him. “The day we met I knew I was going to marry him,” she later said.

Alex, now 46, a dozen years younger than Patricia, is Puerto Rican and sweet-looking, with lovely skin and surprising hazel eyes. She didn’t graduate from college, but she’s bright and pointed, with a gentle, responsive laugh and her own sense of injury. She doesn’t come from privilege. She was born in the projects in Harlem, though, like Patricia, she grew up in Washington Heights. That upbringing didn’t make her feel entitled, and she dislikes people who do.

Patricia Cohen: “I just will never understand his anger, the turning on me.”

Steve Cohen: “She’s a terrorist on a mission to make my life a living hell.”

These days, Alex helps give away millions to charity, shows up at events on Steve’s arm. Still, she wears Gap and drives to Costco, alert to bargains. And she takes care of her man. She doesn’t complain that he works too much; she lauds his devotion to their kids. If he has a bad day at work, she cooks his favorite meal, pasta with anchovies.

Steve lives like a comfy king with his queen in a lavish compound with a fully loaded sports complex: hockey rink and basketball court, swimming pool, and, on the grounds, a two-hole golf course and a home for Alex’s parents. “I don’t need a house this big, but you know what? Why not?” Alex told The Wall Street Journal.

And on the wall hangs the world’s most expensive art. Steve moves the art market, too, often overpaying, which seems part of the pleasure. He spent over $500 million on a Picasso, a Warhol, a de Kooning, a Van Gogh, one of Monet’s Water Lilies. He just picked up a Jasper Johns for $110 million. And he paid $8 million for Damien Hirst’s shark in a tank of formaldehyde, apparently his joke about the hedge-fund world.

Steve made the art decisions, and he left Alex to run the household, including the finances—which means, among other things, she controls her predecessor’s cash flow. It was a special twist of the knife. After all, Alex wasn’t well disposed toward Patricia. Before they were engaged, Alex and Steve broke up four times because he kept returning to that woman.

Alex, who raised a child partly as a single mother, has her own issues with Patricia. “Why didn’t she get a job?” she wonders to friends. Now it’s Alex who combs through Patricia’s bagfuls of receipts and writes the checks. “I paid for every paper clip,” she told a friend, “if it was for the kids,” and that’s over and above the child support. She keeps records of every single disbursement, from a futon for $173 to the daughter’s car and taxi rides, for a bulging $19,800 in 2001, to the son’s car service to school in Riverdale (Patricia thought the kids were entitled to be driven to school), another $6,400. In 2001, Alex wrote checks to Patricia totaling $576,950, though the average annual payment, including child support and all other expenses, was closer to $400,000 while her kids were at home, according to documents. Of course, however generous the sum, it was no hardship for Steve. In 2001, Steve earned $428 million, according to Institutional Investor.

The arrangement drove Patricia crazy, and maybe it would have gotten under anyone’s skin. Steve insisted on being asked for money—or begged, as Patricia saw it—and then expected praise in return. And what he gave was hardly “proportionate,” as she said. She thought her kids were entitled to better. Were they his shabby relations left to daydream about the lavish parties and cushy lives of their half-siblings, like Cinderella dreaming of the ball?

Alex’s son, not even a blood relation, moved into a $3 million apartment in Tribeca. Steve and Alex kept the apartment in their name and offered Patricia’s daughter the same deal, but the daughter declined. She wanted the property in her name. Otherwise it was just one more way to live in the king’s court. Steve refused—he saw it as tough love. He wasn’t going to let his kids live off their father’s success. And also there was the gift tax he’d have to pay, which occurred to him, too.

Still, he wouldn’t let anyone say he ignored his children’s needs. There were years he gave Patricia’s daughter a $100,000 stipend—in 2005, it was $123,000. But a sense of deprivation is deeply ingrained in the kids. The daughter doesn’t even tell anyone that her father is a billionaire. She doesn’t have the money to show for it, so what’s the point?

At times, the struggle with Patricia was unbelievably petty. For Steve, generosity is a complicated impulse. He likes to keep control. He moved Patricia into a new apartment, but shortly after, in a March 22, 2002, letter from his attorneys Bronstein Van Veen, Steve told her that he will only pay for his kids’ “books required specifically in the course syllabus,” adding, “You will be expected to provide the syllabus.” His daughter, a film student at the time, was warned not to buy movies if they could be rented. And then, on June 24, 2002, a letter states, “Mr. Cohen has previously requested and wishes to reiterate that requests should not come directly to him from the children,” as if that would make him uncomfortable.

Patricia and Steve haven’t had a conversation in a decade, a decade in which Steve burnished a reputation as art collector, philanthropist, market genius, and simple Greenwich homebody. But Patricia still believes she knows a deeper truth.

In March 2006, Patricia saw a 60 Minutes segment about her ex-husband that she says finally opened her eyes. Steve had been sued by Biovail, a large Canadian pharmaceutical company that alleged that he plotted to drive down its stock price, which he was betting against. The Biovail suit was later dismissed. Still, in Patricia’s account, the program revealed that Steve was capable of anything. As far back as 1991, she’d accused Steve of hiding his matrimonial finances, but the TV show reawakened her suspicions. She says she felt a sudden duty to the truth, as well as to her financial well-being. And it launched her on an obsessive three-year search into Steve’s business past, involving dozens of calls and tracking down her former husband’s business associates.

In short order, a warning came. Steve planned to continue paying Patricia $9,000 a month, though he would no longer legally owe her a thing. But her snooping had gotten back to him. In October 2007, Patricia says, a message was conveyed through her son: Patricia “should not bite the hand that feeds [her].” Patricia had some savings, but she was in a precarious financial position—and she saw something far more precious than financial security slipping away. Patricia, who’s still single, had devoted her life to her children—it’s her career, as even Steve acknowledged. “[She makes] the children her whole life,“ he wrote, though he didn’t mean it as a compliment. But now they were grown-ups, making their own way. And Steve was insinuating himself back into their lives, throwing money at them, as she saw it (being his usual generous self, as he saw it). He rented an apartment for his daughter in 2006 for about $2,000 a month and bought his son a car at a cost of $32,000.

The kids were still devoted to their mother, but the parental dynamic had shifted, and Patricia felt pushed to her limit. “I no longer have any influence on either of them. I am no longer a parent but a witness,” she wrote in a dramatic October 30, 2007, e-mail to Steve. Patricia was heartbroken by these developments—but also oddly liberated. She told Steve that she was “someone who has nothing at stake,” nothing left to lose, and issued a warning of her own: “If you choose to remember me as someone who is feeble, unintelligent, or lacking tenacity, that would not be correct.”

On August 8, 2008, Patricia went to a city office at 31 Chambers Street to get copies of her divorce papers. She noticed computers that, a clerk explained, house a database of court cases. She punched in her ex’s name and, lo and behold, up popped Cohen v. Lurie, a 1987 lawsuit that she later called “my discovery.”

For Patricia, the documents offered not only a rare glimpse into the near-ruin of the future hedge-fund king but a window into his conniving character. The year was 1986, probably the worst year of Steve’s professional life. He was in a near-panic. The Securities and Exchange Commission was breathing down his neck, suspicious that in December 1985 he’d used inside information when he bet that RCA and GE would merge, ahead of the announcement. In June 1986, the SEC called him to testify, but he refused to answer any questions, invoking his right against self-incrimination. Then, to complicate Steve’s life further, the SEC started nosing around his other investments from the same period, especially those involving Brett K. Lurie.

Lurie was Steve’s “exceptionally good friend,” as Lurie wrote in an affidavit—Uncle Brett to the kids. He was also Steve’s onetime lawyer turned real-estate developer and, later, felon.

Patricia was very interested in the Lurie investments, too. Steve, she discovered, had given Lurie millions of dollars and didn’t at first bother with paperwork. And then she read that he’d tried to disguise his investments by putting Lurie on his payroll. It looked to Patricia like a clumsy scheme to gain a tax deduction (though Steve apparently didn’t go through with it).

By the time of Patricia’s divorce, Lurie was on his way to bankruptcy, and however fishy the transactions, they benefited no one. Steve wrote off his entire investment as worthless, to the tune of $8.75 million. With that one stroke, he’d halved the money he owed Patricia. And yet, as Patricia read the lawsuit, alarm bells went off. Steve had sued to recover only $7.5 million from Lurie. He had ripped her off for over $1 million, it seemed to her.

Steve made it through. The SEC didn’t charge him with insider trading. Eventually he recouped $408,000 from his Lurie investment. He didn’t tell Patricia about at least part of that, but it was less than 5 percent, hardly consequential for someone like Steve. Nor did she know that, as a lawyer’s letter indicates, Steve apparently threw good money after bad—as part of the settlement with Lurie, Steve invested another $1.3 million in the deals, accounting for the discrepancy Patricia finds suspect. But Patricia hasn’t seen that letter, and might not care anyway. For Patricia, it’s not only the specific sums that are telling. She looks at the entire story—suspicions of insider trading and cheating the tax man, and then taking the Fifth and blowing off paperwork—and sees the makings of something big and nefarious: a criminal enterprise, with Steve at its head.

Patricia believes that part of the $25 million with which Steve launched SAC in 1992 came from their profitable real-estate transactions, the seven she’d engineered with her hard work and market savvy. Steve’s view is that this is ludicrous, but for Patricia it’s another element of the deception, and one that cost her dearly.

Patricia’s claims face steep legal hurdles since, among other things, the alleged misdeeds happened so long ago. But Patricia has studied Steve for years, and she feels she’s finally got him where she wants him. “What will he say?” she asked a confidant. “ ‘Yes, I screwed her and my children, but I’m afraid, your honor, that the statute of limitations has run out?’ ”

At lunch with Patricia and her lawyer Kachroo, the food has come and gone. It’s almost evening; outside, the streetlights go on. Patricia says she won’t remarry: “You can’t be that wrong and allow yourself to ever do it again.” Plus, her story with Steve still isn’t over. She looks at me tearfully. “I am the mother of his children. How many people saw your daughter for the first time? It’s not being in love [that’s important] so much as having a history,” she says, as if she almost missed him. Even Steve occasionally seems to remember a more hopeful time. “How did this happen? How did we get here?” he asked a friend.

But sometimes, in a marriage, the past is never gone. For better or for worse. For poorer, or for richer.

Additional research by Sam Dangremond.