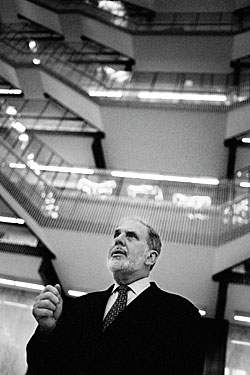

John Sexton, NYU’s president, is doing what he does best: selling. “You want to contrast the way NYU is in the city and Columbia is in the city,” he tells me. Columbia’s campus, sitting at the southern edge of Harlem, is a walled city, the more-than-metaphorical ivory tower. But at NYU, there’s “not a single gate, not a single blade of grass,” which isn’t strictly true, but close enough for a great salesman burnishing his brand.

Sexton is seated at a conference table in his office on the top floor of NYU’s Bobst Library, wearing rumpled navy slacks and a sky-blue sweatshirt from his alma mater, Brooklyn Prep. “Frankly, I dress this way anytime I have an excuse,” he says. When Sexton became president, ten years ago, many believed his drive was to elevate NYU to compete with the Ivy League. In fact, his ambition is grander. He sees the city and the university as a single unit, a node of talent and creativity and, of course, money. And he’s not marketing only to the country’s bright high-school students but also to the global meritocracy. “The analogy that I use is to the Italian Renaissance, when there was Milan and Venice and Florence and Rome, and the talent and creative class moved among those points,” he says, tracing circles with his hands for emphasis.

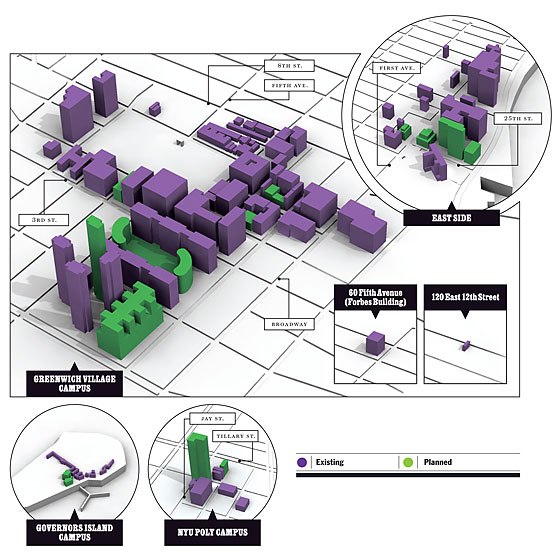

New York, with its population of immigrants and transients of all races, creeds, and socioeconomic categories, not to mention its global reach, is the perfect city to build such a vision, but some changes will have to be made. Big changes. NYU is proposing to add 6 million square feet of new space across New York City in the next twenty years, with half the growth taking place in the historic blocks of the Village—the equivalent of three Javits Centers. The proposal, known as NYU 2031, is the culmination of four and a half years of design work by a team of world-class architects that included Toshiko Mori, a Harvard professor and former chair of Harvard’s architecture program. In the Village, NYU is proposing to build four new buildings, including a 38-story hotel and residential tower and a 1,400-bed freshman dorm alongside the I. M. Pei towers that the university owns. Sexton’s vision, and his argument, bears some resemblance to the famous G.M. adage of the fifties: What’s good for NYU is good for New York City, and vice versa. And what it means in practice is that the core of downtown New York is on its way to becoming a college town.

Sexton’s pitch to me is that NYU needs this space if it is to compete for top faculty and set the agenda for cutting-edge research in emerging fields like neuroscience and genomics. But the university’s plan to double its rate of growth over the next two decades has sparked a bitter turf battle with neighborhood activists who have mobilized to block NYU’s moves. NYU’s expansion and the conflict it inspires expose a deeper debate about the changing nature of the city and NYU’s role in it. A generation ago, New York was a place you went when you graduated from college. Columbia, and especially NYU, were urban afterthoughts.

But in the span of 30 years, NYU transformed itself from a regional commuter school to a national university that attracts 90 percent of its students from outside the city. NYU now has more than 40,000 students, making it the largest private university in the country. The university’s view is that this growth has been a boon to the Village and the city. “Having 40,000 students is like having year-round tourists,” says Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at NYU. “They spend their parents’ money and don’t consume too much of public service and add to the nightlife.” The Bloomberg administration welcomes this growth. “The city has more students in colleges and universities than Boston has people,” says Seth Pinsky, president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation. “What’s important about the educational sector is that it allows us to showcase the city to the leaders of tomorrow. It helps increase the intellectual firmament of the city. The thoughts and research that take place inside our university campuses help us seed business outside the university setting. It provides a double whammy.”

Universities—and this is an argument that Columbia makes, too—are a recessionproof employment engine. But this may come at a cultural cost, with the university culture smothering the things that have always been most distinctive about downtown. Harvard Square is lovely—but it’s also not the vital center of a real city, nor are the main drags, for instance, of Ann Arbor or Berkeley. Universities create their own gravity: the more massive, the more dominant.

Where Sexton sees a new Renaissance, many in the Village see a new feudalism, with Sexton cast in the role of domineering overlord. NYU has been growing at a rate of 125,000 square feet per year since its founding. “The institution seems to think this is about manifest destiny. Unfortunately, it’s not about manifest destiny, it’s megalomania,” says Susan Goren, a vocal community activist. “I remember the Village with Bob Dylan on the bus, Mick Jagger at the Lone Star. All it is now is NYU kids texting and walking into you wherever you go.”

Much of the anger in the Village is rooted in NYU’s poor development track record. The university’s history of overbuilding goes back two generations, to the days of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs. The Times’ legendary architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable described NYU in 1964 as having a “consistent blindness to the area’s architectural and historical features.” NYU has only further antagonized the Village by constructing buildings like the hulking Kimmel Center, which towers over Washington Square, and the 26-story high-rise on East 12th Street that it bought and converted into a 700-bed freshman dorm. “They’re the new Robert Moses,” declares David Gruber, the chair of Community Board 2’s arts-and-institutions committee.

The Moses analogy can be crude in its own way—Marc Jacobs and Carrie Bradshaw, not to mention the financial industry, did their part to transform the Village into a theme park—but it is certainly true that NYU is the largest single force shaping development in the Village. When he took office, Sexton vowed that NYU would improve its approach to development and sought to communicate with community leaders. He agreed to join a task force run by Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer to allow the Village to influence NYU’s designs. Sexton is a conciliator. He hugs nearly everyone he meets. But he is also a brilliant debater who relishes a fight. When I ask if he’s worried about whether activists will try to block his plans, his eyes narrow. “We live in a time of slogan politics and demagoguery, and if you’re going to take that personally, you shouldn’t be the president of a university,” he says flatly, “and I never do.”

Sexton is fond of quoting the late Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who once said that if you “want to create a great world city, establish a great university and wait 200 years.” It’s a view shared by Marty Lipton, the legendary M&A lawyer and NYU’s board chair. “It’s been 58 years since I attended my first class at the NYU Law School, and I’ve lived in or close to the Village ever since,” Lipton told me. “What NYU has done is not just change for the better its immediate surroundings in the Village; it’s NYU that gave rise to the shift of the cultural and social center of Manhattan south of 14th Street.”

Some of the people who were painting and playing and clubbing and shopping and just plain living in Greenwich Village in the past few decades might take issue with that statement. But regardless of whether NYU is the egg that gave birth to downtown’s chicken, the university is now on the verge of swallowing the chicken.

On a muggy evening back in June, about 200 Village residents packed the floral-print ballroom inside 75 Morton Street’s Activity Center. The meeting was hosted by Manhattan Community Board 2. The board called the meeting to listen to NYU’s architects present their designs for a 400-foot-tall hotel to be built on the landmarked I. M. Pei–designed superblock in the heart of the Village. A few days earlier, NYU had leaked the renderings of the proposed concrete-and-glass tower to The Wall Street Journal. Neighborhood reaction went nuclear. Representatives from the Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation circulated through the crowd, handing out leaflets. Local press lined the back wall of the room. NYU’s lead architect, Mark Husser, opened his presentation but was immediately shouted down when he explained that NYU’s planned building would be taller than the adjacent Pei towers. “In this case, we felt it should be distinct and it should be taller,” he said.

“How much taller?” yelled a voice from the audience.

Husser started to answer. “The new building is 300 and …”

“How many stories?” another cried out.

“Thirty-eight stories,” Husser responded, eliciting gasps and groans.

“What are the existing buildings?” came a shout.

“Thirty stories,” he said.

“How many feet?”

“The existing building is 300 feet high.”

“And your building?”

“Three hundred eighty-five feet high.”

And from there, things only got worse. The room exploded with applause when Andrew Berman, the executive director of the Greenwich Village Society of Historic Preservation, stood up and said NYU’s plan is “a little like BP saying they show respect for the environment.” A woman from the audience summed up the collective sentiment nicely. “This is a crime against the Village, and it must be stopped.”

To hear NYU tell it, the university has learned from past mistakes and is seeking to build in harmony with the neighborhood. “This is a really strong historic-preservation move for us,” Toshiko Mori told me. The plan calls for adding a slender glass tower that will house the hotel and faculty condos on the Pei site. According to one senior NYU official, the hotel idea, which isn’t finalized, is being pushed by NYU’s executive vice-president, Michael Alfano, who oversees the university’s finances. If the hotel gets approved, NYU plans to partner with a hotel operator to run it. It will be open to the public, but NYU is building it to cater to out-of-town faculty attending conferences on campus and visiting parents. On the block to the north, NYU wants to build a pair of bulbous academic buildings in the interior courtyard of Washington Square Village. And to the east, the plan calls for taking down the bunkerlike Coles Gymnasium and replacing it with a seventeen-story mixed-use building with a dorm, academic space, a supermarket, and an underground gym. NYU says that although it plans to build up, it will improve the open space by putting a lot of facilities underground and through better landscape design while adding much-needed retail services to a desolate block. It’s an audacious plan that will require NYU to get approval from the city to rezone the area with a commercial designation, a major bone of contention. “Most of the development would come on property we already own,” Sexton says. In NYU’s view, Moses already did the damage, so adding large structures to those blocks won’t harm the Village. “In a way, the dirty job was done by Robert Moses,” Mori says. “It’s a scar. It makes a lot of sense to frame the site where large buildings already exist. It does the least amount of damage to the existing context.”

NYU is, in terms of students, the largest private university in the country. If the current development plan, titled NYU 2031, is approved, it will have a campus to match—centered in one of the most hallowed neighborhoods in the world, with outposts in Brooklyn and Governors Island. Should downtown be a college town? We're about to find out.

Map by Jason Lee

Some of NYU’s architects think it’s wrong to apply the terms of the old neighborhood battles to this fight. “There are people who have this leftover kind of half-baked Jane Jacobs attitude,” said Matthew Urbanski, NYU’s lead landscape architect. “They [think] she was saying ‘no no no’ to everything. She was a very positive person.”

“Jane Jacobs would be the first person on the barricade saying, ‘NYU, we can’t let you take over and build more and more,’ ” counters Andrew Berman, referring to the author who was the patron saint of small-scale Village life.

This time, NYU wanted to get the politics right. The university approached its strategic plan with the discipline of a political campaign. It hired an outside PR consultant and staged open houses to solicit feedback from residents. To appease opponents, NYU has been unsparing in criticizing its own architectural mistakes. Kimmel is an example of “what not to do,” Mori says. Some see politics in this kind of blunt talk. Kevin Roche, the acclaimed Irish-American architect who built Kimmel, is angered by NYU’s views. “That’s one way to get on in the world,” he said of Mori’s comments. “I would never comment about another person’s work like that. It’s silly. That’s a part of the tactic of trying to get the neighbors onboard.”

“Sexton’s vision seems to be: What’s good for NYU is good for New York, and vice versa.

Building on the Pei blocks brings major risks. While NYU’s architects believe adding the hotel in the middle of the block will preserve unobstructed views in Pei’s original towers, building on the landmarked site requires approvals from the Landmarks Preservation Committee. And there was always the chance that Pei might speak out against the proposal. Berman had spoken with him privately in a bid to win him over. “We wanted to make sure Andrew Berman couldn’t call him up and get a quote from him saying his site is sacred,” one person involved in NYU’s planning told me. “One word from Pei could have killed the whole thing.”

And so in February 2008, NYU scheduled a meeting with the 93-year-old Pei to present its designs. Pei sat quietly as Husser, the Grimshaw architect who designed the new building, presented the renderings for the NYU hotel. And then he spoke. To their relief, the only request he made was to clean the Picasso statue on the site.

“We kept him abreast out of respect,” Mori told me. “Historic buildings can be a dead artifact, but it gives them a longer life once a new building creates a new dialogue. In that way, cities survive.”

In February 2005, Mike Bloomberg invited Sexton to lead a two-day retreat on Staten Island for senior City Hall officials. With the mayor’s reelection campaign ramping up and agendas for a second term being drafted, Bloomberg had tapped Sexton to lead a discussion about expanding the city’s economic base beyond the traditional sectors of finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE, in the parlance of urban planners). “He asked me to talk to the commissioners about what would make New York City an idea capital in 2050,” Sexton recalls. It was a topic Sexton had been thinking a lot about. Since being appointed president of NYU, in 2001, after a celebrated run as dean of NYU Law School—where he bulked up the faculty by poaching academic all-stars and boosted fund-raising—Sexton had become something of a scholar-statesman-futurist, racing around the world giving speeches and interviews to promote his utopian vision of a tomorrowland where universities are the centers of a new type of metropolis built on ideas and intellectual capital. “There’s a way the pope and Rudy Giuliani were both right when they said New York City is the capital of the world,” Sexton says, “so how do you sustain that?”

Before Sexton briefed Bloomberg’s team, he wanted to coin a slick slogan to sell them on a post-FIRE future. On his way to the meeting early in the morning, he was still struggling to come up with a label when he thought of his wife, Lisa, who at the time was the president of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, the philanthropic arm of billionaire Revson’s Revlon company. Sexton was reminded that Revson’s biography was titled Fire and Ice. The combo stuck. “I came up with the phrase that FIRE was ‘necessary but not sufficient.’ What was needed was ICE: intellectual, cultural, education,” Sexton says. “People think I’m an intellectual, so people think ‘Fire and Ice’ came from the Frost poem or this great Valhalla myth that connects to it. I’m confessing this on the record, I guess,” he tells me, pausing to consider whether to finish the thought. “In fact, the phrase comes from a lipstick.”

Shortly before I sit down with Sexton, he had welcomed Olivia Woodward into his sun-filled office. Woodward, the teenage daughter of Shaun Woodward, Gordon Brown’s secretary of state for Northern Ireland, was in town on a college tour visiting Harvard, Yale, and NYU, and Sexton had agreed to sell her on NYU. He had first met Woodward about two years ago, when he was in London meeting with Brown. “The last time I saw her dad was when I, a young guy from Brooklyn, got to go up to visit with the prime minister and have breakfast with him,” Sexton later told me. After breakfast, Sexton had been introduced to Woodward and told her to consider NYU in a few years. “I got an e-mail from [her father] a few weeks ago. He wrote, ‘Olivia’s never forgotten that meeting; we’re actually coming. She’s a junior now, beginning the application process.’ ”

Sexton’s pitch to Woodward is the same he delivers to me: New York is “in and of the city.” In recent years, Sexton has become an acolyte of the urban theorist Richard Florida, author of the book The Rise of the Creative Class and the director of the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto. Florida told me that cities like New York are “the greatest college campuses in the world.” His ideas meshed with Sexton’s belief that cities need universities to attract this new class of global intellectual. It was a tweak of Thomas Friedman’s theory of a leveling of the playing field. “Instead of a flat world, it’s flat with spikes of excellence,” Sexton says.

In the not-so-distant future of Sexton’s imagining, NYU will become the hub of a network of world cities interconnected by NYU branches. And so this fall, NYU debuted a branch in Abu Dhabi, welcoming 150 freshman who will be awarded full NYU degrees in four years. This is partly a business decision. Unlike its Ivy League rivals, NYU has a chronically underfunded endowment—just $2.5 billion compared to Harvard’s $28 billion—a legacy of NYU’s history as a second-tier regional commuter school, as well as the fact that it’s plowed money back into development. Sexton’s uptown rival Columbia has triple the endowment with just half the students. The Abu Dhabi deal provided a major source of funding: The Abu Dhabi government donated $50 million up front and is committed to footing all the costs of NYU’s Abu Dhabi campus, plus lavishing more dollars on NYU in the future. Sexton is looking for his next outpost, and advanced talks are under way with the Chinese government to open an NYU in Shanghai or Beijing, with similarly generous financial terms.

In his former role as dean of the law school, Sexton competed fiercely with the Ivies, and as president, he understood that NYU needed to dramatically increase its physical plant if it was to challenge the elite schools for top scientists and researchers. NYU’s student population had grown to 38,000. Partly, growth was a business consideration: NYU pays for most of its operations out of student tuition. More students meant more revenue for new academic programs. But by 2001, NYU was overcrowded. “I had a yearlong transition process, and one of the headlines that came out of that process is we were deeply space-deprived,” Sexton says. Specifically, faculty had been pressing him to build more housing. Housing plays a major role in academic recruitment, and NYU needed more apartments to lure professors to the city. “Issues about housing play a large role in recruiting,” says Sylvain Cappell, professor of mathematics at NYU’s famed Courant Institute. “I would say this to candidates: ‘Being in New York is like Bucharest in the old days. One more bedroom is a big deal.’ ”

Sexton’s ambitions haven’t sat well in all corners. Liberal professors have expressed deep reservations about the relationship with Abu Dhabi, a régime with a questionable track record on human rights; tolerance for gays, lesbians, and Jews; and free speech. “In my mind, it’s blood money because it’s sweated labor of the migrant workers,” says Andrew Ross, a university union leader, professor, and vocal critic of the Abu Dhabi plan. “There’s a lot of pressure not to cause a fuss about this.” This fall, Ross and his allies’ fears were stoked when NYU professors who showed up to teach found out that Abu Dhabi had reneged on a promise to pass legislation that would protect NYU’s campus by creating a free-speech “cultural zone” on the island. At a faculty meeting in September, Ross confronted Jess Benhabib, interim dean of arts and sciences, over the matter. “The promise was that there would be a bubble on the campus, and no legislation was passed to that effect,” history professor Mary Nolan said, recalling the meeting. NYU says the régime will protect academic freedom. “They have kept every promise,” says NYU spokesperson John Beckman.

To Nolan, Sexton’s vision places growth above all else. “NYU is becoming like many universities: It’s increasingly a corporation, and run like a corporation, in a very top-down way. Every university positions itself in the academic marketplace. This is the new game. Power has been sucked up to the top level.”

For Sexton, globalization is the logical expression of NYU’s unique history: Albert Gallatin and 99 other citizens established NYU in the nineteenth century without campus walls at a time when the leading universities—Harvard, Cambridge, Yale, Princeton—inhabited the pastoral-campus ideal. Sexton sees global expansion as the continuation of this openness. “New York is literally the miniaturization of the world,” he says. “We’re the first ecumenical university. And New York is the first ecumenical city. It’s the first experiment in the miniaturization of the world and whether or not humankind will succeed in creating a community of communities or whether a clash of civilizations will occur.”

Last year, NYU and Sexton agreed that he would stay in place until 2016. Recently, NYU presidents have served ten-to-fifteen-year terms. At 68, Sexton is liable to be on the final leg of a journey that has taken him from his home in Belle Harbor, in the Rockaways. In 2007, his wife, Lisa, suffered an aneurysm and died. She was 54. Sexton was devastated. In some ways, NYU has become like his family, and he has poured his life into realizing his vision. He is famous for drinking as many as twenty cups of coffee per day and sleeping just five hours per night. Many see Sexton contemplating questions of his legacy, but he dismisses the idea when I bring it up. “I don’t think of my legacy,” he said. “Twenty Thirty-One is not worth a life. Maybe the opposition to 2031 is for some people.”

Sexton’s focus on development came at a time when universities across the city were on a land grab. Uptown, Columbia was clashing with residents in West Harlem over plans to build a seventeen-acre campus by eminent domain. Fordham pursued 1.5 million additional square feet. The New School, too, under president Bob Kerrey, was trying to expand its downtown footprint. Seeing all this, Scott Stringer, Manhattan borough president, sought out Sexton to see if he could change the dynamic citywide. Stringer had the idea to form a task force comprising NYU, Village residents, and politicians to bring the warring factions to the table. It was essentially an effort to forge a new model for development, where the community and NYU could hash out their differences and craft a plan that would mitigate some of the outrage. “Everyone understood the relationship had to change,” Stringer says. “Their my-way-or-the-highway approach a generation ago was a great mistake.” Stringer told Sexton that NYU needed to come up with a long-term development plan. Sexton agreed. “I said, ‘We’re not doing it this way. You have to put all your cards on the table,’ ” Stringer recalls.

Around the time Stringer and Sexton agreed to form the task force, NYU’s relations with the Village had hit a new low. In 2005, NYU announced it was partnering with the Hudson Companies, a Manhattan developer that had already begun work on demolishing the St. Ann’s Church on East 12th Street, leaving the façade and erecting a 26-story building on the site. The brick structure, the tallest building in the East Village, is architecturally undistinguished, to say the least. The dorm became a political wedge issue. NYU was embroiled in a labor dispute with grad students over Sexton’s refusal to recognize their union. The neighbors, represented by the union’s law firm, filed for a temporary injunction to block the construction, but the injunction was dismissed. NYU got its dorm. But turning the development into a dorm came at a heavy political price. “We didn’t add a square foot!” Sexton told me. “Did we change the age of the people? Yeah! Okay, we did. Unless you’re going to say students are venal and yuppies are not? It wasn’t the substance of the issue, it was about a general symbolic politics and a churning and a deconstructionism and making things as difficult as possible, and the demagogues got involved.”

NYU recognized 12th Street was politically costly. “It was a defining moment for us: How did we get this so wrong?” says Alicia Hurley, NYU’s vice-president for government affairs.

NYU took a new development tack. Historically, it had pursued a maximalist approach to real estate, buying up land whenever it became available. Now it staged open houses with Village residents to solicit feedback. Sexton pushed his architects to look for building options outside the Village. It was decided that the nursing school would move to the East Side of Manhattan, and NYU drew up plans to build a campus of as much as a million square feet on Governors Island. But NYU’s internal analysis showed it would still need to add some 3 million square feet in Greenwich Village. Architects began meeting weekly for three-hour sessions to draft a long-range plan. The focus of development began to center on the superblocks south of Washington Square. The blocks were a creation of Robert Moses and the urban-renewal campaigns of the mid-fifties. In the early sixties, NYU bought the land for just $10.50 per square foot from the struggling developer and commissioned I. M. Pei to build three Le Corbusier–inspired towers. The blocks were initially derided by Village residents but have since been reconsidered; in November 2008, the Pei towers received landmark status from the city.

Meanwhile, relations inside Stringer’s task force were becoming strained. NYU officials felt they were making concessions and grew frustrated that their new openness wasn’t being rewarded; Village leaders felt NYU was ramming through its plan and ignoring their calls to consider building in the financial district, where lower-Manhattan community leaders have sought out NYU to build. Sexton told me there are certain buildings that just have to be in the Village. “If students have to walk between classes, you can’t have those outside of a zone,” he says. “Certain activities like the gym and so on have to be nearby, otherwise students can’t get to them to use. Freshman dorms, it’s much more important they be in close, simply because freshmen are typically coming from all over the world or the country and it’s their first time in New York, and you need them in a protected environment.”

“We’re not talking about putting it in Staten Island or Westchester,” David Gruber, a task-force member, says when I mention NYU’s argument. “We’re talking about two fucking subway stops away. You can’t do that?”

NYU’s pitch was “like BP saying they show respect for the environment,” said Andrew Berman.

It’s a recent morning, and Gruber and I meet over coffee at a café on Bleecker Street. Gruber has lived in the Village for the past 30-plus years and has become a leading community voice on NYU matters. He’s bald, with tufts of wild hair on the sides of his head, and looks like the aging hippie that he is. After graduating from Columbia, he ran off to India. “I went to see lost horizons and meet the Dalai Lama,” he says. “Then we get up to Kashmir, and everyone is doing something—they’re either smoking hash or they’re buying carpets.” After returning to New York in the mid-seventies, Gruber spent a career making and losing small fortunes in various business ventures. Gruber’s now doing well in real estate. He tells me he came to the NYU debate with an open mind, but the university’s tactics have radicalized him. “They’re real fuckups,” he told me earlier.

The task force suffered another blow last summer when Berman got a call from a neighbor on Macdougal Street who had snapped a photo of NYU construction crews demolishing a wall at the historic Provincetown Playhouse, which the university was converting to offices for the law school. Berman was outraged. NYU had promised the task force it would preserve the original bricks of the theater in which Eugene O’Neill once worked.

When Gruber ran into Alicia Hurley at a task force meeting days later, he was incredulous. “What, was it an accident?”

“It was a mistake,” Hurley replied. “Someone in my office thought it was okay to do it because they need to support the foundation.”

“Are you crazy? Are you out of your mind?” Gruber exploded. “You could have supported that wall!”

“It’s done. What am I supposed to do?”

Gruber had a solution. “Fire your whole staff.”

“I can’t do that,” Hurley said.

“You’re saying you didn’t know about it? Your office doesn’t buy toilet paper without checking with you, and you’re telling me a wall comes down? Tell me who it was, and fire them.”

Hurley wouldn’t budge, and for Gruber the episode still stings. “When someone says some junior person allowed that to happen, that strains credibility,” he told me. “I don’t believe that’s what happened.”

Hurley told me the Provincetown controversy is a political effort by opponents. “They view the entire project as a disaster. That’s a pile-on effect,” she said. In a way, she’s right to be frustrated. NYU made concessions in the original Provincetown design to appeal to community concerns. They scuttled blueprints for a ten-story building and replaced it with a seven-story brick building that blended in with the surrounding blocks. “[The opposition] doesn’t show any proportionality. Even when NYU does something good,” says John Sutter, the Villager editor-in-chief and a longtime NYU observer. “This was almost an infantile point of view.”

In late March 2010, after four years and 50 meetings, the Stringer task force published a 40-page report. The document contained strong language and called NYU’s “proposal to put 2.8 to 3.5 million square feet in the area, or anything close to that figure … overwhelming.”

While Stringer had formed the task force to build consensus, the closer NYU came to releasing its strategic plans, the more the group was becoming unglued as NYU and its opponents jockeyed for position in the looming public battle. Soon, confidential details of the task force were leaked to the press. A month later, Stringer disbanded it.

Stringer told me the official reason was that the task force’s off-the-record format wasn’t appropriate now that NYU had submitted its plans to the city for public review. There is a debate about whether the effort was successful in checking NYU’s growth. During the final meeting of the task force this summer, Terri Cude, a spokesperson for the Community Action Alliance on NYU 2031, repeatedly asked Gary Parker, NYU’s director of government and community affairs, what the university had changed about its plans since the task force had issued its report. NYU was pressing ahead with its bid to build the hotel and academic buildings in the Village.

“What did you change?” Cude asked.

“Well, Terri, they’ve informed our conversations, because—”

Cude interjected. “I asked you what have you done since March 25, since we gave you our recommendations?”

“The task force has been a resounding failure,” Berman recently told me. “It’s 100 percent a political effort to get them to secure the public approvals they need for this plan. They’ve made people willing to give them a chance, but people were disgusted with the process. NYU wasn’t willing to move an inch. They were unwilling to live up to their commitment.”

NYU says it did follow the recommendations, by focusing to build on its own land and seeking growth outside the Village. “Now fully half our growth will be outside the Village,” NYU’s Beckman told me.

Stringer said the opposition benefited from having NYU put its plans on the table. “The biggest contribution is we now know what the plan is,” he told me. “What was so frustrating about this development process is it wasn’t transparent. You may hate the NYU development proposal, but at least you know what it is.”

Now both sides are bracing for a messy public fight. Last month, NYU submitted its plans for the fourth tower on the Pei site to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and last week, Community Board 2 held a meeting in which attendees denounced NYU’s proposal. It’s the first step of a complex approvals process that will unfold over the next year. If NYU hoped that Pei would remain quiet—he won’t. Last week, I spoke with Henry Cobb, a founding partner of Pei’s firm. Cobb told me that Pei hasn’t made up his mind about the hotel design—there’s a chance he could speak out against it. “We will comment at the appropriate time, and our comment will be clear and concise,” he said.

NYU has made some missteps already. This spring, as it announced the 2031 plan publicly, it had to withhold more-detailed architectural renderings at the last moment, because it had yet to float the proposals by City Planning officials, according to one source familiar with the matter. (NYU didn’t comment.) NYU can’t afford many more stumbles. One of the most controversial elements of the plan is its request to gain control of narrow strips of open space along Mercer Street and La Guardia Place, among others, that belong to the Department of Transportation—land that was left over from Moses’s failed plan to build the much-derided expressway through the Village. “This is kind of a Jane Jacobs versus Robert Moses fight of the gods,” Gruber says. The earliest NYU could begin building would be 2013. But both sides understand that whether this plan gets approved will determine the shape of the Village for the next generation.

Near the end of our interview, I ask Sexton what would happen if NYU is thwarted in its campaign to build. Sexton told me that NYU can build on land it owns nearby when a building restriction expires in ten years. “We can grow anyway! I mean, we grew for twenty years before. If that’s denied, we have an as-of-right building that will be five feet away. Which we’ll do! Maybe we’ll be forced to add seven stories to the Catholic Center.”

Sexton says this with a smile, but his intention is clear. “What’s good for NYU is good for the city” is a slogan that, one way or another, New Yorkers are going to have to get used to.