The steel gate slides open, and into the visiting room walks Harrison David, 20 years old, unshaven and slouching, wearing a putty-colored Manhattan Detention Center uniform. In keeping with prison procedure, he didn’t know who was coming to see him until just before he walked through the door. He’s polite enough to shake my hand and candid enough to tell me he’s disappointed to see me. “To be honest, I thought you were going to be some of my fraternity brothers,” he says, “bringing me some socks and underwear.”

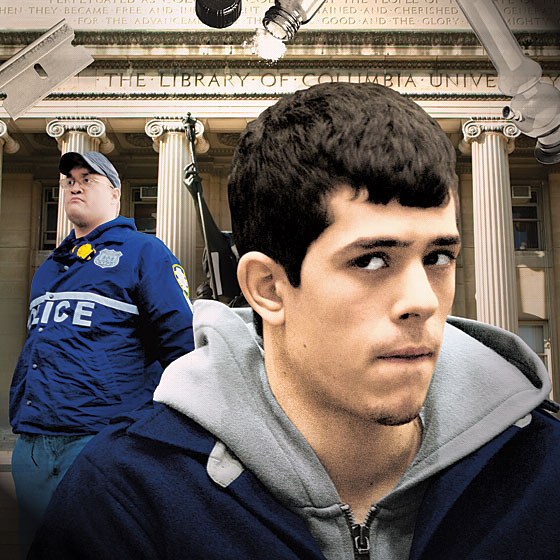

Fraternity row isn’t his home anymore. Eight days earlier, David was a dark-haired, boyish financial-aid student who roamed the Morningside Heights campus with 5,600 other undergraduates. He was an engineering major who once talked about wanting to be, literally, a rocket scientist. Now he stands accused of being the lead offender in a campuswide drug-dealing ring, the largest operation of its kind at a local college in recent memory. In a dawn raid on December 7, NYPD officers formed bunker teams carrying battering rams and stormed the dorm rooms of David and four other students, then arrested them and hauled them downtown in front of local-news cameras. “Operation Ivy League” was said to involve five months of undercover work, including $11,000 in marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy, Adderall, and LSD buys. “This is no way,” police commissioner Ray Kelly deadpanned at the press conference, “to work your way through college.”

David was the first Columbia student the police investigated, the one who inadvertently led cops to the other four, and the only one accused of selling cocaine, a higher class of felony that carries a greater likelihood of jail time. He was also the only one said to be connected to a drug supplier implicated in a violent kidnapping plot—and the last of the five to be bailed out. His father, Dave David, a cosmetic surgeon and sometime TV talking head from Massachusetts, had visited his son but hadn’t put up the money to free him. “I guess he’s doing what he thinks a dad should be doing, trying to teach me a lesson,” David says. “I tell you what. If I had a kid who was in jail, I’d bail him out first and then do whatever parenting I’d do with him.”

With his Southie mumble and scowl, David could pass as a refugee from the rougher precincts of Boston. The truth is another matter. He grew up comfortably in Wrentham, Massachusetts, a Boston suburb best known for its outlet mall. He was the oldest of six children. His parents divorced when he was 6 years old, and the children shuttled between the two houses for much of their childhood. After a year at a private boarding school, David attended the public King Philip Regional High School, in Wrentham, where he studied aerospace engineering and was president of the science honor society. Schoolwork came easily to him—he says he was one of two kids from King Philip to be accepted into an Ivy League university—but David seemed to work hardest at not being thought of as a grind. He played tennis, ran cross-country, went to parties, and smoked his share of pot (he has a marijuana-related youth offense, a felony that he pleaded down to a misdemeanor). For his speech as class salutatorian, David had to submit the text beforehand, but didn’t want to, so he wrote some nonsense and gave it to the principal, then spoke off the top of his head, ending by quoting Jimi Hendrix to a crush of applause. Three years later, Harrison is still proud of that speech.

David arrived at Columbia in the fall of 2008. He pledged Alpha Epsilon Pi, known as a Jewish frat, and skated through classes, just as he had in high school. He says he kept up a 3.2 grade-point average at the engineering school. From his dorm room, in John Jay Hall, he also quickly became known as one of the school’s more industrious pot dealers. He’d run up and down the John Jay stairs to sign buyers in. The transactions took place in his room, quickly and with a minimum of conversation. “He did what he did like a trade,” says a classmate.

Pot at Columbia is, for a certain segment of the student body, like a public utility—it’s just there. A student dealer typically finds his way to one of a handful of fairly well-known off-campus suppliers who service the school. Some of those suppliers are former Columbia students; others grew up dealing to current students elsewhere in the city; still others are slightly bigger time, dispensing large shipments of pot they get directly from Seattle or California. The students who hook up with those suppliers are prized by some not just for the air of cool that dealing can sometimes confer but for assuming the risks of obtaining pot so their classmates don’t have to. For the most part, nobody has to leave the confines of Morningside Heights. Most students who use drugs at Columbia do so recreationally, and substances harder than acid are relatively rare. If anything, the school stands out only in how highly functional the students can be despite the partying. “The difference is they’re doing homework too,” says a friend of the accused students.

From left: Adam Klein, Christopher Coles, Michael Wymbs, and Stephan Vincenzo. Photo: Rudy Sulgan/Corbis (Columbia); John Marshall Mantell/Sipa Press/Newscom (Klein); Steven Hirsch/Splash News/Newscom (Remaining). Illustration by Gluekit.

David and the four other students who were arrested weren’t running an organized drug ring so much as catering to various niches of the marketplace, police say, in a loosely coordinated way. David met Chris Coles freshman year, and Coles became a friend. He is African-American and grew up in the D.C. area. He studied philosophy and hung out with other black students and social activists. Friends say Coles seemed to struggle to make his tuition payments.

David and Coles both hung out with Stephan Vincenzo. Everyone knew Vincenzo; half-Mexican and half-Colombian, he was a high-fiver and backslapper. While getting a full ride as one of 1,000 Gates Millennium Scholars nationwide, he wrote poetry for the Spectator and worked as a model and party promoter. During freshman-orientation week, he invited his entire class, via Facebook, to a party that’s still talked about, and in time, his party-promoting business branched out around the city. “People used to laugh at the modeling,” a friend of Vincenzo’s says. He was parodied in the campus “Varsity Show” and had lighthearted stories written about his legend in a campus journal called The Fed. “It’s funny that everyone wants to know what I’m doing,” Vincenzo once joked. “But it comes with a price. I can’t drink, I can’t holla at a girl without everyone knowing what I did.” Vincenzo’s actual name is Jose Perez, but he wanted something flashier; Vincenzo is a nod to Al Capone. Despite his Gates money, Vincenzo had living expenses to pay for, and a role to play as a downtown impresario.

David thought of Adam Klein as something of a younger brother. A fencer from a middle-class family in New Jersey, Klein was studying neuroscience and hoped to become a doctor. Klein spent his summers working at a Dairy Queen; his mother is a fifth-grade teacher, and his father was recently laid off from a job selling art supplies. He was fascinated by LSD’s effect on brain chemistry and used some of his money to go to Bonnaroo, Rainbow Gathering, and Burning Man. Mike Wymbs is a fraternity brother of Klein’s. His father is an international-business professor at Baruch College, and his mother is a tax lawyer; they live on the Jersey shore at Beach Haven. Apparently the wealthiest of the five students, Wymbs, like David, was enrolled in the engineering school, where he maintained a 3.5 GPA. Majoring in applied math, he served as vice-president of the student council.

Each of the five students had his own tribe and allegedly worked his own niche. David moved into the AEP house, Coles lived in the Intercultural House, Vincenzo rushed Pi Kappa Alpha, Klein pledged to Psi Upsilon, and Wymbs lived in the East Campus high-rise dorm. Police say the students specialized in different products as well: David and Coles pot; Vincenzo pot, Adderall, and ecstasy; Klein LSD; Wymbs ecstasy and acid. Like Macy’s and Gimbels in Miracle on 34th Street, the five friends would allegedly send customers to one another now and then—but if this was a cartel, it was extremely low-key (no one has been charged with conspiracy). “It wasn’t like people were saying, ‘If you want this drug, go to this guy,’ ” says one customer. “You had to know in order to know.”

David says he got $37,000 in financial aid each of his first two years, but needed to pay $54,000 in tuition and living expenses. He closed some of that $17,000 gap each year with a combination of Stafford and private loans. Drug dealing helped close some of the rest of it. A campus dealer might buy an ounce of pot for $380 and sell it for $65 per eighth of an ounce bag, or $520 an ounce, netting $140 per ounce—if he didn’t smoke any of it himself. A hardworking dealer who moves, say, ten ounces a week could take home $1,000, or maybe $40,000 in the course of a school year. Still, all told, David tells me he currently owes as much as $50,000 in loans.

The spring of his sophomore year, friends say, David became more intense. “The consensus is that he had a coke personality,” says one source, “where you need that extra uninhibited push—because you don’t give a fuck.” On spring break, Harrison went to the Ultra Music Festival in Miami, staying in a suite at the Eden Roc resort with his friends, living large. “I can’t say a lot about what I did there,” he tells me, “but we made some money and had a lot of fun.”

Until then, a source says, David hadn’t been in the habit of selling outside his little circle. But he was exhilarated now, financially motivated, and ready to take some risks. “One guy he used to work with had a bit of a falling out with him over the summer,” says another source. “He was saying that Harrison wasn’t discreet.” In June, David found an apartment share for the summer in Hell’s Kitchen and started looking to buy some coke.

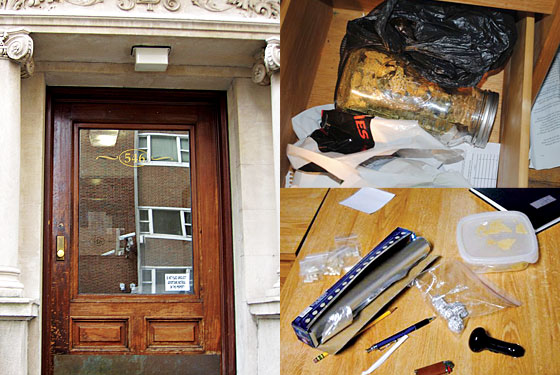

Counterclockwise from left, 430 East 6th Street between First and A, where Miron Sarzynski lived; marijuana plants and air pistols police say they found in the apartment.Photo: DNAInfo/Benjamin Fractenberg; Courtesy of Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City of New York/NYPD (Remaining)

The alleged supplier of the Columbia drug ring is a scrawny, fidgety 23-year-old East Village pot dealer named Miron Sarzynski. When I visit him at Rikers Island, he cries and vows more than once, as ingenuously as he can manage, to turn over a new leaf. “I never thought it could happen to me,” he says. “There’s two sides to me.” He’s not trying to get through prison by being tough. Compared with Harrison David, he’s a complete mess.

Sarzynski says he came to America from Poland when he was 13 and went to the High School for the Humanities in Manhattan. His parents are divorced. His mother works at Columbia University Medical Center, and his father stayed in Poland. He drifted into dealing, he says, after dropping out of the Borough of Manhattan Community College. “I wanted to make my own money,” he says, and a security job and two clerical jobs didn’t last. Last summer, he and his girlfriend, Megan Asper, moved from Journal Square in Jersey City to a tiny studio on East 6th Street, where Sarzynski set up two storage closets with LED lights and a ventilation system, each able to hold about twenty marijuana plants, as well as the fixings for DMT, a synthetic hallucinogen.

“We’re in love,” he tells me of Asper. The two had met about six months earlier in the webcam chat room on the Stoners United social network. They never made much money selling pot; Sarzynski even worked part time cleaning apartments, advertising on Craigslist.

It isn’t clear how David met Sarzynski. Sarzynski says it was through an NYU student dealer who had a high opinion of David, and a source close to David says it was via a close friend of David’s at Columbia. In any case, they met in June, when David was living in Hell’s Kitchen. David’s share of the rent that summer was $1,300 plus utilities. He was dealing to pay the rent, a source says, and worked construction a few days a week. He was also using more cocaine. “I didn’t even go down there,” a friend of another of the accused students says, “because it was just him doing a lot of lines.”

Sarzynski became David’s coke dealer (although he insists he never dealt to any of the other four Columbia kids), and the two men fell into a routine. They’d meet on the corner of 49th Street and Tenth Avenue, not far from David’s apartment. Sarzynski never sold David more than an ounce of coke at a time—a typical deal would be twenty or so one-gram bags at about $38 or $40 per bag. David could have then sold each bag for anywhere between $60 to $100, depending on the quality and the demand. Sarzynski’s suppliers were three guys from Queens—men he later told police were named Waffel, Pono, and Karate and who “took steroids” and “moved massive amounts of drugs.” He’d hooked up with them through Pono, whom he had known in high school.

“Why do you think I have to do this shit? My dad won’t pay tuition.”

Two months earlier, in April, the NYPD says it had received an anonymous complaint on its Crime Stoppers hotline about drug dealing at Columbia. The police sent an undercover officer to try to make some buys—a young-looking guy with long dirty-blond hair who went by the name of John. Friends of the accused students don’t seem to remember John. He apparently wasn’t posing as a student and didn’t attend classes or have friends at the school. According to the city’s Special Narcotics Prosecutor Bridget Brennan, the university was unaware of the entire operation until shortly before the bust. The police, it seems, didn’t want to have to get Columbia involved in helping to establish his cover.

According to one source, John found his way to David through the same Columbia friend who had introduced David to Sarzynski a few weeks earlier. John told David that he was selling drugs on a film set downtown and was looking for supply. David never stopped to think about why a downtown dealer would come looking for drugs at Columbia. Either he was too reckless or too interested in the money to care. The first buy recorded by police—more than 25 grams of pot, or more than enough for ten joints—came on July 29 at 7 p.m. inside an apartment at 517 West 113th Street. There was another pot buy on August 5 at 8:30 p.m. and a third on August 11 at three in the afternoon. David continued selling to John, a source says, even after getting angry at him for putting too much information in his text messages. “He texted like a retard,” a source says, but David never picked up on the clue.

Counterclockwise from left, Alpha Epsilon Pi, on West 114th Street, where Harrison David lived; capsules alleged to be ecstasy and a jar containing marijuana police say they found in the house.Photo: DNAInfo/Leslie Albrecht; Office of the Special Narcotis Prosecutor for the City of New York/AP Photo (Remainging)

When John saw David lay out some lines during one deal, he started pressing him for coke—so David sent John to Sarzynski. John’s first videotaped coke purchase from Sarzynski, police say, was on August 17 at about 9:15 p.m. near First Avenue and 4th Street. John allegedly went back to David for pot and coke on August 24, then back to Sarzynski’s apartment for more coke on the 25th. At about this time, police say, David was doing a few deals with another dealer from Brooklyn named Roberto Lagares. Whatever he was doing with the coke, he appeared to be going through it too fast for just one dealer to keep up.

David says he came back to start his junior year in September to unwelcome news. Owing to changes in the economy, he says the university told him, he would no longer be receiving financial aid. David appealed the decision and won back about $10,000 in aid, but still didn’t know how he was going to pay for the rest of his tuition or his expenses. David says his father suggested he go into the military. The idea may have seemed unlikely, but David considered it. He talked to recruiters and was veering toward the Army; they’d pay for his college once he came back, or he could transfer his credits and enroll for a free ride in a military engineering program. But he walked away from that plan. He liked Columbia too much. He wanted to be with his friends. He decided to keep taking classes and deal with problems as they came up.

On September 7, the police orchestrated a coke buy with David and then a pot deal on the 23rd they say involved both David and Coles. A source says once David referred John to Coles, John eventually made the rounds and met other Columbia dealers. Coles allegedly sold John more pot on October 6. Coles and Vincenzo allegedly sold Adderall to John on October 13. David, Coles, and Vincenzo all allegedly sold him pot on October 25. When he wasn’t doing the circuit at Columbia, John was doing double duty downtown with Sarzynski. He bought cocaine and a vial of LSD on September 14. On that deal, John brought along another undercover officer—a slightly older, muscular Italian guy with a mustache. Sarzynski was told his name was Rob.

After one last deal on September 21, John stopped his visits to Sarzynski, and Rob became Sarzynski’s regular customer. Rob came along for a coke deal with Sarzynski on the night of September 30 and met one of Sarzynski’s coke suppliers—one of the three men from Queens. Two weeks later, on October 13, Rob got a phone call from Sarzynski, who was furious about not getting $4,200 that his Queens connections owed him. He said he wanted revenge.

Sarzynski admits to it all now. “I was very emotionally angry,” he tells me. Rob seemed like a tough guy to Sarzynski, and he asked Rob if he knew anyone who could help him kidnap one of the dealers for ransom. He says Rob got back to him and said he had two black friends and some Spanish friends who were “itching” to do it. Sarzynski outlined his plan to Rob a few days later, October 17, inside a stairwell of his East 6th Street apartment building. The conversation was recorded. “I want my four Gs,” Sarzynski said. “You take everything else. It will pan out because that guy makes all the money for them. He is the head. They need that guy, they will pay money for him … We’ll tell them, ‘You’re going to give us $10,000 right now, or they’ll never see you again,’ and they’ll bring it down. They’ll want no one to die over $10,000.”

At about 1:30 p.m. on October 20, police say, Rob picked up Sarzynski and headed to Queens to stake out where the would-be kidnapping would take place. Sarzynski says Rob brought a Canon camera and took photos of the Queens guys. As he rambled on in a rage, Sarzynski’s plan kept changing. “We should just take the main guy,” he said first. “Then just fucking go up to his main place and get all the money. Or just make one of their soldiers do it. They’re going to be shitting their pants, because I know they got the money, and they’ll give it up because they don’t want to die. And if that guy dies, the business dies.” Then Sarzynski went on about how Asper, his girlfriend, was also furious about getting ripped off. “She called them fucking skanks,” Sarzynski told Rob. “She was, like, ‘If we can’t find anybody, we’ll do it ourselves.’ ” Finally, he fantasized some more about what he’d do if he could. “I would go behind them with a fucking Taser, taking everything they got, and then—pop! In the head.” After that, “something nasty,” he said, “like put a few drops of acid in his mouth and then leave him there. I would have done something very nasty.”

A week later, on October 27, Rob drove to Sarzynski’s building on East 6th Street and asked him to come outside with a bottle of LSD. It was 11:10 a.m. About ten minutes later, Sarzynski came out and handed him the bottle.

“I bagged those two last night,” Rob said.

“You’re kidding me!” Sarzynski said.

“You gotta be my lookout,” Rob told him. “We’re going to their place.”

“But they’ll see me!”

“No they won’t. You just have to wait outside.”

Sarzynski got even more excited. “Okay. I had a dream last night we got them.”

Then came the police. They cuffed Sarzynski and Rob, too, maintaining Rob’s cover, and shoved them both into a police van. Inside, Sarzynski kept talking. “If they go to my apartment, I’m fucked,” he told Rob. “I got weed growing, my girlfriend is there, I got acid. I’m going to give up everybody.”

The police raided the apartment and brought out Megan Asper.

“Oh, good,” she said when she saw Rob. “I thought you were a cop.”

With Sarzynski locked up, Operation Ivy League continued through November. Using John and, perhaps, some other undercovers, police say they fanned out and made buys from all five of the accused students. Coles led them to Vincenzo, they say, then Vincenzo to Wymbs and Klein. In November, the cops say they bought LSD from Klein twice (sixteen acid-laced candies in all), ecstasy, pot, and Adderall from Vincenzo, mollys (ecstasy in powder form) four times from Wymbs, pot twice from Coles, and pot three more times from David.

On December 5, police picked up David’s other alleged supplier, Roberto Lagares, near where he lived in the Kingsborough Houses in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Two days later, on the Tuesday before the end of fall classes, they rolled down Fraternity Row at dawn, surging up 114th Street, clogging the stairwells of four Columbia apartment buildings, pounding through doors, and walking away with a supermarket of acid-laced candy, four bottles of LSD, scales, ecstasy, Adderall, pot, and $7,200 in cash. The busts weren’t without glitches—they got Klein’s room at Psi-U wrong, because he’d traded rooms with someone on his floor. For a moment, frat brothers have been heard saying, the wrong man had an NYPD gun pointed in his face.

To some at Columbia, the arrests seemed arbitrary, or worse. The semiotics of the term “Operation Ivy League” were an endless source of discussion. Was the NYPD indicting the whole university in a class-tinged ploy for publicity? Coles reportedly complained that when they were taking Vincenzo out, they made him wear a Columbia sweatshirt for the benefit of the news cameras. Others said Columbia, with its considerable political clout, should have stopped the busts and handled the matter on-campus. “How could they have allowed it to escalate to this point?” wondered a close friend of one of the arrested students. Some started speaking of the arrested students as scapegoats, martyrs, even causes célèbres—“the Columbia Five.” Some say the drug business has slowed on-campus. “No one trusts anyone,” one student told me. Others say that’s not so. “There’s more bowls of pot to fill now,” says one former customer. “And I already know people who are filling them.”

Typical bail in a first-time nonviolent drug offense is usually around $5,000. But David got $75,000, Coles $40,000, Klein and Wymbs $35,000, and Vincenzo $30,000. A few of their lawyers privately floated conspiracy theories—not just that Manhattan Supreme Court Judge Michael Sonberg wanted to make an example of some Columbia kids but that the judge was feeling political pressure because of a case from a few weeks earlier. In November, Sonberg had granted a crack dealer named Lawrence Elliot a month to care for his sick dad before entering prison, and two days later he allegedly raped and robbed a City College student. “In hindsight, the judge deeply regrets the outcome,” a spokesperson for the court had said. The D.A., one of the students’ lawyers told me, “hung him out to dry on that.”

At the end of the day, it was almost certainly David’s carelessness, or at least his bad luck, that led to the arrests. “The rest of the guys were selling to their friends at very little profit,” says a close friend of another one of the arrested students. But David, the source says, had tried to go beyond that. Had David not stepped up the level of his enterprise or run into Sarzynski, it’s unlikely the police and Columbia would have ever been involved, however opportunistic or unprotective their subsequent actions may have been.

Five days after my visit, on Monday, December 20, Harrison David’s father came through with the bail money, and David was released. It’s likely that he and the others will receive plea-bargain offers from the D.A.—although David, the only one charged with a class-A felony, may find it hard to avoid significant jail time. The reforms of the Rockefeller drug laws allow for judges and the D.A. to offer reduced sentences. But the high visibility of this situation means that won’t happen easily. “This is not a typical case,” says one lawyer close to the matter. “You’re not exactly calling the D.A. and saying, ‘Come on, what’s the offer?’ ” Coles and Klein were seen packing up their rooms at Columbia, and it’s assumed the others have moved out too. The university has yet to take action on the five students’ enrollment status.

A source close to David says he has spent a lot of time thinking about the friend who connected him to John and Miron Sarzynski. Maybe the friend was a patsy—maybe he was betrayed. During our visit, David told me he was upset about being in prison—not scared straight like Sarzynski, exactly, but his eyes were more open now. Some of the guys in prison seemed innocent to him. It made him think more about the system and how it’s designed to bring some people down. One inmate heard David’s life story and told him he thought it would make a great book. All his adventures. Why did David do it? “Why do you think I have to do this shit?” he told police when they picked him up. “My dad won’t pay tuition.” (His father has subsequently said he has contributed “since day one.”)

While he was in jail, David spent a lot of time playing a card game with the other inmates called cutthroat. “It’s a fun game,” he told me. “The loser does twenty or 50 push-ups or whatever. So I’ve been doing push-ups all day.” He pulled up his uniform and flexed his right bicep. One day, he said, he’d like to teach cutthroat to his fraternity brothers.

Additional reporting by Kirk Carapezza and Elien Becque.