The 55 inaugural addresses before the one Barack Obama will deliver next week have run the gamut from poetic (rarely) to prosaic and platitudinous (often), but all have shared a common premise: the promise of newness. Though claims of fresh starts and clean breaks are de rigueur for incoming presidents of both parties, the Democrats have tended to be more explicit—and extravagant—about it. Franklin Roosevelt spoke of “writing a new chapter in our book of self-government,” John Kennedy of “creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law.” Jimmy Carter said his election augured “a new beginning, a new dedication within our government, and a new spirit among us all.” Bill Clinton proclaimed (redundantly) in his first inaugural that “a new season of American renewal has begun,” and in his second he uncorked a veritable neoteric orgy: heralding the coming of “a new century in a new millennium … on the edge of a bright new prospect in human affairs”; calling for a “new vision of government, a new sense of responsibility, a new spirit of community”; intoning that “the promise we sought in a new land we will find again in a land of new promise”—invoking that final phrase five times for good measure.

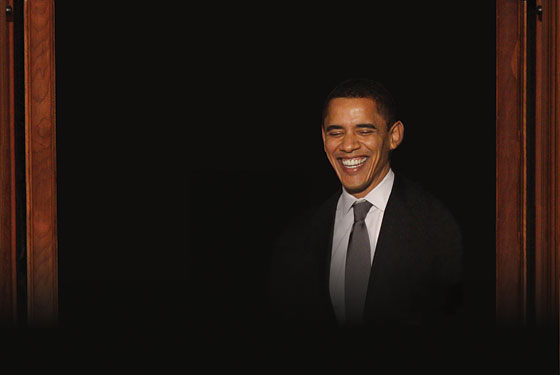

Obama, of course, will not need to strain so hard to cloak himself in the aura of novelty (though his people apparently aren’t taking any chances—the event’s official theme, borrowed from the Gettysburg Address, is “A New Birth of Freedom”). As much as the country has grown accustomed to seeing Obama’s mug on their TV screens, the sight of a black man taking the oath of office still promises to shock. But the signifiers of Obama’s newness extend far beyond his race: They are generational, temperamental, intellectual, experiential. He has no real precedent as an occupant of the Oval Office.

Not that this has forestalled the punditocracy from the nonstop analogizing of Obama to his predecessors. He’s the new JFK, the new FDR, the new Lincoln, the new (albeit inverted) Reagan. And the attempts to pinpoint Obama along the ideological spectrum have been similarly unrelenting. The right looks at his economic-stimulus plans and spies an old-school, big-government liberal. The left looks at the tax cuts in that same plan, his hawkish foreign-policy appointments and decidedly nonprogressive economic ones, and his invocation invitation to Rick Warren, and wonders, “Hey, was this guy really serious about all that centrist talk during the campaign? We thought he was only kidding, that he was one of us all along!”

Obama is difficult to pigeonhole not simply because he’s new but because of the newness of the moment that he—and we—inhabit. It’s a moment dominated by an economic crisis that’s shaken bedrock beliefs about the infallibility of free markets. A moment when a revised architecture of power is arising globally, challenging America’s status as an unrivaled superpower. When the networked age has finally arrived, inciting the implosion of the broadcast paradigm that governed politics in the Industrial Age. When the country is being transfigured demographically, hurtling toward becoming a majority-minority nation.

This crescendo of forces produced Obama, made his ascension possible. Now he has a chance to shape the new era, to leave his stamp on it. “This really is the first presidency of the 21st century,” says Simon Rosenberg, head of the Democratic advocacy group NDN. “Those who try to hold on to twentieth-century descriptions of politics are going to be disappointed and frustrated by what’s about to emerge in the new administration, because American politics no longer fits into the old boxes—and neither does Obama. For better or worse, what he is doing is building a new box.”

By every indication, Obama’s efforts to build that box are being guided not by any hoary orthodoxies or deep partisan convictions but by a strict adherence to the doctrine of pragmatism. He brings to the task not just a new team and a new agenda but the makings of a new kind of political machine. The questions now are whether he can turn his rhetoric about transcending polarities into an effective governing strategy; whether he can forge a cohesive legislative coalition to advance his aims; and, if he can and does, whether the Democratic Party will still look remotely like itself—or more like, well, him.

Every president aspires to transform his party into a graven image of himself—but few are actually able to pull this le parti, c’est moi maneuver. Obama, however, is in a stronger position than most in this regard, in no small part because of his mastery of the media and technology that dominate the new era.

Three days after Obama won the White House, I happened to be in San Francisco for the annual Web 2.0 conference, moderating a panel on the impact of the Internet on the election. I began by observing that 2008 struck me as being like 1960: a campaign in which a new medium (TV then, the web now) emerged as not just important but dominant—the prime arena for political communication and engagement. The claim was meant to be provocative, spark dissent, but none of the panelists disagreed. Arianna Huffington went so far as to maintain that “were it not for the Internet, Barack Obama would not be president; were it not for the Internet, Barack Obama would not have been the Democratic nominee.”

Huffington is reliably quotable, if not always quotably reliable, but that day she was exactly right, I think. Beyond Obama’s consistent clarion message of change, the two essential ingredients of his success were his campaign’s fund-raising and organizing prowess, and neither would have been possible without the web. His team’s innovations were built on the groundbreaking work the consultant Joe Trippi had done for Howard Dean in 2004. “We were the Wright brothers proving that you could actually fly,” Trippi once told me. “Four years later, the Obama campaign is landing a man on the moon.”

The huge sums the Obama campaign harvested from small donors via the web are justly famous. But the scale of its web-enabled grassroots network was nearly as prodigious—and just as consequential. A database containing a staggering 13 million e-mail addresses, at least 3 million of them belonging to donors. Two million active users and 35,000 self-starting affinity groups on MyBarackObama .com. A million cell-phone numbers of people who requested the campaign send text messages to them. Countless names on volunteer lists from Obama’s sprawling get-out-the-vote effort on Election Day—by which time fully 25 percent of the people who pulled the lever for him were already connected to the campaign electronically.

The political implications of this network are impossible to overstate. “They have basically invented their own party that is compatible with the Democratic Party but is bigger than the Democratic Party,” the Republican media savant Stuart Stevens, who helped to elect George W. Bush twice, argues. “Their e-mail list is more powerful than the DNC or RNC. In essence, Obama [was] elected as an independent with Democratic backing—like Bernie Sanders on steroids.”

“American politics no longer fits into the old boxes,” says Simon Rosenberg, “and neither does Obama. For better or worse, what he is doing is building a new box.”

Now, having dragged electioneering kicking and screaming into the new century, Obama and his people are grappling with how to harness their network to help Obama govern. Virtually since Election Day, they have been debating the putative shape of what they like to call Obama for America 2.0, with much of the focus on a central choice: Should the network be folded into the DNC or housed within an independent entity? The risk for Obama in pursuing the former path was clear: a possible turnoff for the millions of loyalists who bought into the Obama brand but happened not to be Democrats. On the other hand, though an outside group would have given Obama a power base separate from the DNC, he would also have been less able to exercise control over its agenda.

With the selection last week of Obama’s friend, Virginia governor Tim Kaine, to chair the party, the question has more or less been answered: Much of the campaign’s grassroots operation, I’m told, will reside at the DNC. What Obama is wagering is that, with some clever branding (read camouflage), the fealty of his non-Democratic followers to him personally will overcome whatever nausea they experience owing to the partisan affiliation. And though the move has been interpreted as a sign of Obama’s empowering the DNC by having it absorb the network, I suspect that the opposite may happen. The Obama network—with its greater resources and zeal—may effectively absorb the party.

In the shorter term, it’s clear what Obama intends to do with his new machine: put it to work lobbying on behalf of his legislative agenda. Around the country, countless Obamaphiles are itching to pummel Capitol Hill with e-mail or show up at congressional town meetings. Presidents often attempt to go over the heads of Congress to the voters, but never before has one directly enlisted them to pressure their elected representatives, especially those of his own party. “Obama and his political operation have assets that no president has ever had before,” says Micah Sifry, co-founder of the Personal Democracy Forum. “We have no previous model for this—it’s completely new.”

Obama will sorely need the juice his network can provide, because the obstacles arrayed before him in rescuing the economy grow more daunting every day. Economics has never been Obama’s strong suit. During the Democratic primaries, his main point of vulnerability against Hillary Clinton was his comparative inability to speak persuasively on the topic. It wasn’t that Obama didn’t proffer a decent-enough set of economic policies. It was that he seemed incapable of building a compelling narrative around them, an explanatory framework that made sense for voters of the mounting anxiety they felt about an economy—a financial system, a mortgage market, a jobs-and-wages scenario—on the brink of unraveling. Even in September, when the credit-market meltdown proved the turning point in the general-election campaign, Obama’s glaring advantage over John McCain was one of temperament and demeanor—of projecting an air of calm and steadiness and having his shit together while his rival was flailing and skittering all over the ice—rather than substance.

So it’s ironic, to say the least, that the first defining moment of the Obama regime happens to revolve around matters macroeconomic—dealing not just with a nasty and potentially prolonged downturn, but with a wrenching, epochal crisis of capitalism on a global scale. Like all such traumas, this one offers an opportunity for genuine greatness. But it poses a severe test of his mettle from the moment he removes his hand from that Lincoln Bible with which he’s being sworn in.

And even before that! In his first full week in Washington as president-elect, Obama was consumed with previewing his stimulus package—and absorbing rebukes to it from his nominal allies. The criticisms were not vicious, to be sure, but they were both substantive and political. Their issuers ranged from congressional Democrats (Tom Harkin, John Kerry) to lefty intellectuals (Paul Krugman, Josh Marshall). On substance, the core complaint was with the ratio of tax cuts (too high) to public investment. On the politics, they were myriad: that Obama was being too solicitous of GOP support; that he was “ceding the initiative to Congress, which is odd since he’s immensely popular and Congress is wildly unpopular,” as Marshall put it; and so on.

That Obama has taken more lumps from liberals than conservatives is telling—and may foreshadow a persistent dynamic in his administration. For some, the size of the tax cuts in the plan confirmed that he is a closet centrist. Others, however, saw a different culprit afoot. “They’re scared of the Senate, they’re scared about the filibuster, they’re scared that the Republicans will keep them from getting shit done, and that they’ll wind up with a failed presidency,” says a prominent Democratic strategist.

Obama’s extraordinary degree of political security frees him from kowtowing to either the left or the right. He can redefine the party on his own terms.

There may be some truth to that—Obama and his gang are pretty sharp when it comes to arithmetic—but I suspect something deeper is going on here. Somethings, really. The situation that Obama confronts in Congress is more complex than the solid Democratic majorities on both sides of the Hill suggest. Much of what’s been going on looks like institutional chest-puffing, as senators seek to convince Obama (and themselves) that they are still at least mildly relevant in the face of the phenom that is the president-elect. (Consider this plaintive quote from Max Baucus the other day: “Senators are senators; they’ve got ideas, too.”) Making this stress worse is that, until two months ago, most of these preening grandees were senior to Obama and that none of them has ever lived under the rule of a president elected from their ranks.

Obama has seen up close (courtesy of Bush) what happens to a majority party when the president runs roughshod over Congress as a matter of course. His campaign was premised on a theory of change that rejected the notion that constant, witless, all-out warfare is inevitable. He believes in the big table, in the possibility of “disagreeing without being disagreeable,” of bridging divisions both between the two parties and, by implication, within them, too.

Wishful thinking? Maybe. But Obama’s new approach is more than that. The tax cuts in Obama’s stimulus proposal are likely to command support outside Washington from voters of many stripes; with an eye to his network and the pressure it can wield, he is crafting a plan that appeals to what the Democratic strategist Ed Kilgore has dubbed “grassroots bi-partisanship.” As he did in his campaign, in other words, he is working politics from the outside in rather than the other way around.

He is also looking down the road at the other items on his protean agenda. Soon Obama will be turning to health-care reform, energy reform, and, apparently, entitlement reform. As Pat Moynihan was fond of pointing out, these are not the kinds of votes you win 51-49; epic legislation acquires an epic margin or it fails. Obama understands that to be the kind of president he aspires to be requires building coalitions on a grander scale than most occupants of the Oval Office ever have within their reach—and thinking of, planning on, a two-term window in order to get it done.

That time horizon is based on more than sheer self-confidence or grandiosity, however. Not long ago, a Republican guru of my acquaintance was brooding on who might be his party’s nominee in 2012—and questioning the sanity of anyone who’d want to be. “To run against Obama, you’re going to have to raise $1 billion,” he marveled. “Who in their right mind would want to try and do that to run against an incumbent president?”

Financial disadvantage, however, may be the least of the impairments that Obama has inflicted on the GOP. For more than 40 years, the Republican Party’s success was premised on the Southern Strategy, which exploited racial anxiety to cleave the “solid South” away from the Democrats. But as Rosenberg observes, “Obama’s election is the ultimate repudiation of the Southern Strategy. It has left the Republicans totally decimated; I don’t think they’ve been this far out of sync ideologically with the American people since the thirties.”

Obama’s sense of optimism about 2012 is, no doubt, only further enhanced by the unlikelihood that he’ll face a serious primary challenge within his own party. One of the fringe benefits of having placed HRC at the helm of the State Department—and don’t think this didn’t occur to Obama’s political hands when the deal was going down—is that it lowers to the vanishing point the prospect of her taking him on.

For Obama, the implications of this extraordinary degree of political security are enormous. It frees him from kowtowing to either the left or the right, to set about redefining the party in his own terms. Hardly anyone doubts that the moment for such a recasting is at hand—though they tend to imagine the future simply as an updated version of the past. “This isn’t 1933 or 1961 or 1981 all over again,” says Rosenberg. “It’s 2009, and what Obama has done is create a redirect of the entire political culture—new media, new demographics, new electoral map, a whole new set of governing challenges that will be the basis of the next 20 or 30 years. He’s gonna be a critical piece of that arc. And it’s not a restoration. It’s a period of reinvention.”

Unless, of course, it isn’t. No great feat of imagination is needed to see how the whole project could end in tears. The stimulus fails. Things continue to fall apart. A new Great Depression ensues. And Obama is blamed and soon enough finds himself out on the speaking circuit with pal (ahem) Bill Clinton.

Yet the astonishing thing about this moment is that virtually no one—besides the charter members and presiding officers of the wackjob caucus and the wingnut chorus—is yearning for that outcome. Perhaps it’s because the exogenous circumstances are so dire, but the desire to see Obama succeed is broad and deep among citizens of all persuasions. After the past two decades of politics as total war, what a blessed and glorious relief. A president that most everyone is rooting for? That may be the newest thing of all.