A year and a half ago, if you told most New Yorkers that Anthony Weiner would be running for mayor at the top of the polls, the response might have been: What city, what century, what dimension?

Mayor Weiner? Back on a windy night in 2012, when the former congressman and I sat down to dinner at a Flatiron-district café, what were the chances of that? It was less than a year past the infamous “sexting” scandal, when, after a period of bald-faced lying, Weiner admitted, yes, he was the man in the gray cotton briefs. The admission led to his ignominious resignation from the U.S. Congress. Once seemingly full of boundless promise, the youngest man to serve on the New York City Council, elected to the House of Representatives seven consecutive times, Weiner was now universally type-slugged as “the disgraced congressman,” consigned to the political ghetto of those who had let the little head do the thinking for the big head. The fact that his name was Weiner added an irresistible touch of tabloid predestination to the entire tawdry affair.

“Growing up in Brooklyn, I thought I heard all the Weiner jokes, but I guess I hadn’t,” said the then-47-year-old politician.

In the interim between then and now, through many therapy sessions and myriad apologies both public and private, Weiner, known for his lean-and-hungry yon Cassius look and crocodile smile, has arrived at a variety of ways to express his innermost feelings on the “thoughtless,” “stupid,” “dishonorable” sexting episode, a “failure of judgment” that had “let so many people down.” He’d come to understand his “blind spots,” the way his single-minded drivenness had caused him to develop “this HD focus on the path forward and a fairly blurry take on the world around me.” It was only when he “stopped lying,” especially to his wife, Huma Abedin, whom he’d married less than a year prior to the scandal and who was then pregnant with their child, that he began to breathe again.

Back in 2012, however, halfway into what he now refers to as “my hiatus,” Weiner’s talking points were less well articulated. He seemed a shambling figure with the furtive, chastened aspect of a teenage boy caught with a cache of stroke books under his mattress. The events since the scandal first broke were like “being in a movie,” he said. He had no idea where the narrative would take him. This inability to see around the next corner was accentuated by a recent conversation he’d had about possibly writing a book about the scandal and its aftermath.

“They think it has to have some plotline, like my rise, my fall, how I bottom out, feel all this remorse, have an epiphany, and then come back,” Weiner said with a shake of the head, as if his character arc could ever be so neat. “I’m supposed to be sorry, sorry in this way you’re supposed to be sorry … but I don’t know if it’s hitting me like that.”

This didn’t mean he wasn’t sorry. He was monumentally sorry. He was mostly sorry about Huma, whom he loved and who had done nothing to deserve the nightmare he’d cast her into. For months, Weiner had done his best to convince Huma’s Muslim family that he was the exact right nice Jewish boy to be granted the hand of the extraordinary Ms. Abedin in holy matrimony. Then there was that other family. Huma was among Hillary Clinton’s most trusted, not to mention most photogenic, aides. Often seen whispering in the ear of the secretary of State, Huma was almost routinely referred to as the Clintons’ “surrogate daughter,” right alongside Chelsea. By the power invested in him, the Big Dog himself had pronounced Anthony and Huma husband and wife.

Now Weiner had done this mortifyingly shameful thing, held the exemplary Huma, whom James Carville pointedly called “one of the most popular figures in the Democratic Party,” up to ridicule. It was as if this stellar woman, who could have married anyone, had by the mechanisms of unfathomable fate wound up with the booby prize: Out of the best and the brightest, she chose him, Anthony Weiner. Humiliation and blame hung around the slumped former congressman like a shroud.

It had turned cooler by the time we left the restaurant. From across the street, I watched Weiner navigate his Ichabod Crane frame through the night air, baseball cap pulled down to his ears, as he made his way to his new apartment on Park Avenue South. The baby was born now, “a great, great kid,” his marriage remained intact. This was what sustained him, Weiner said. With Huma often still traveling with Hillary, the once peripatetic Weiner, a man who’d schedule ten events on a single Sunday, had become a house husband, giving his son a bottle, changing his diapers, watching him grow. To be responsible for the intimate well-being of another human being besides himself, to bunker down beyond the reach of the leering public eye, offered a degree of peace.

Video: Anthony Weiner’s Journalism Adventure

Not that Weiner could claim to be sure of anything at the time. The truth was he seemed to still be in a state of shock, a character in the creep-show movie of his own making.

So now, in mid-July 2013, dropped down midway between plot points of the Anthony Weiner comeback saga, what is the concerned citizen to think? It is a conundrum most recently underscored by the even more outlandish copycat candidacy of Eliot Spitzer. This is New York, and Spitzer and Weiner are nothing if not New Yorkers, but how much show-me-yours-and-I’ll-show-you-mine can even the most diverse of electorates take? Anthony and Eliot: This was a government? At least Spitzer was only running for comptroller, some gnomish position. Weiner wanted it all, to be the 109th king of the hill in a procession that dated back to Peter Stuyvesant’s wooden leg. Yet, knowing what you knew, could you really bring yourself to pull a lever for the man—entrust him with the leadership of the beloved hometown?

Amid this melodrama is the all-too-serious fact that the upcoming mayoral election will likely be a crossroads in both the immediate and long-term history of the city. Many think that once the reign of Mike Bloomberg, an anomalous product of one man’s wealth and power, comes to an end, the clock will be reset to the old-school political tumble New York has always been known for: the turf battles between ethnic entities, the knock-down, drag-out between labor and management, and a swing back to the public sector. But twelve years is a long time and this is a different city. It looks different, and it feels different; the days before bike lanes and $4,200-a-month studio apartments grow more remote by the moment.

The new mayor will have to deal with the real problems Bloomberg will leave behind—income inequality, inadequate housing, failing public schools, over-aggressive policing, creeping generic yuppie/hipster gentrification—while still maintaining the go-go atmosphere of a twentieth-century city charging headlong into the 21st. It is a challenge that presents the Democratic Party with an opportunity for great success or cataclysmic failure. After all, these are the same Democrats that have lost every mayoral election since 1993 despite having a six-to-one advantage in voter registration over the Republicans. For most newer, younger New Yorkers, Bloomberg and Giuliani are the normal state of affairs, not machine machers like Robert Wagner or even Ed Koch. My 23-year-old son, a New Yorker born and bred, has lived through the crack era, the conquest of crime via CompStat computations, the horrors of 9/11, the rise of Brooklyn, the tourist influx, the stock-market crash, Hurricane Sandy, and who knows how much $20 gourmet pizza, and none of that happened under a Democratic administration save three years of David Dinkins highlighted by the Crown Heights riots.

With this history, it’s no surprise that the Democratic mayoral forums have been greeted with much frustration and dread. It wasn’t that the candidates were so bad. Each came equipped with requisite up- and downsides. Comptroller John Liu is personable, knows the money, comes from an emerging segment of the electorate, but he is likely fatally damaged by the federal investigation into his campaign funds. Public advocate Bill de Blasio is tall and well liked by progressives, but you can’t remember anything he says five minutes later. Bill Thompson amazed everyone (himself included) by coming within five points of Bloomberg in the 2009 election, has union support, but reeks of hackdom, plus Al D’Amato loves him—and what’s up with that? Then there’s City Council speaker Christine Quinn. In line to be the first woman and gay person to occupy City Hall, with her burnt-orange hair and blackboard-screech pronunciation, Quinn has the look of someone who could actually be a mayor of the City of New York, to tourists at least. But she’s saddled with the time-bomb baggage of facilitating Bloomberg’s hated overturn of the term-limits law. When a leading candidate in your once-dominant party’s most contested primary election since 1977 is a widely perceived subverter of the democratic process, accused partner in a Faustian bargain with the ruling billionaire, this is a problem. All of which meant that Weiner had an opening.

“They’re pygmies. I hate to say it, but they make Bloomberg look good,” said one lady, a retired legal secretary, assessing the field at a Brooklyn mayoral forum in early April. “I came in thinking anyone but Quinn; now I’m anyone but all of them.”

“What about Weiner?” I asked. The congressman’s entry into the race was barely a rumor at the time.

“Anthony Weiner?” the woman replied slowly, as if re-pixelating the image of a long-dead relative. “I like Anthony Weiner,” she finally said. “He was an idiot, but put Anthony Weiner up against this bunch and he’d do well. He’d blow them away.”

Others at the forum expressed similar views. Bloomberg was a disaster, people of color couldn’t even get home from their poverty-wage jobs without being stopped-and-frisked. Someone with political chops and plenty of moxie was needed to stand up. “Yeah, why not Anthony Weiner?” said one transit worker. “Weiner’s a fighter. You see him go up against those Republican assholes back in 2009, 2010? Everyone else sitting there just taking it—Obama too—and Weiner’s the only one screaming back. That’s a hell of a lot more important to me than whether he showed off his cock.”

That was it, the Weiner hope. Call it just one more symptom of a broken system, but seemingly devastating reports decrying Weiner’s high-handedness and failure to pass meaningful legislation while in Congress tended to miss the point. To many New Yorkers, it didn’t matter if Weiner threw a salad against a wall and was a raving a-hole to work for. Congress wasn’t the political battleground that mattered. What did matter was all those page views that Weiner generated during the famous House-floor flip-out over supposed Republican foot-dragging in delivering federal subsidies to injured 9/11 workers. Weiner’s made-for-TV neo-lefty bombast and welcome big-city snideness might have been grandstanding—but it was grandstanding you could believe in.

In the mid-spring New York Times Magazine article that all but announced his entry into the race, a newly Zen Weiner mused about how, if he ever returned to electoral politics, “I might not be so good at it.”

After Weiner officially jumped in with a YouTube video in late May, the above comment would prove prophetic. Across the great metropolis, from banquet rooms in Inwood to stifling old union halls in Corona to offices in Harlem, through Gravesend, Maspeth, and on the Grand Concourse, Weiner traveled to mayoral forums and campaign events, a thrilling cook’s tour of New York’s ever-transforming array of peoples and passion. Only the candidates remained the same, parroting near-identical answers in the South Bronx and Borough Park. One hoped Weiner, cut from classic New York wiseass cloth, noted incisive molder of message, might spice up the mix. But, perhaps rusty from all that time on the DL, Weiner, often bolting to his feet to deliver head-stratchingly rambling commentary, was certainly not blowing anyone away.

He often seemed to be winging it. At a forum held in the temple-of-capital offices of the Kirkland & Ellis law firm on the 50th floor of the Citigroup Center, Weiner suddenly went all Bolshevik, declaring that big Manhattan firms were mistaken if they thought they could sustain themselves “dealing with rich people,” because “you’re going to run out of them sooner or later. There are only so many oligarchs who are going to buy apartments, only so many millionaires who can sue each other.” You could appreciate the outer-borough class antagonism, but a few days later, in Harlem at Al Sharpton’s National Action Network on 145th Street, Weiner, likely the last man on Earth rocking a BlackBerry holster, turned inexplicably wonky, droning on about his 60-20-20 affordable-housing plan (“60 percent market, 20 percent affordable, 20 percent low-income”). The audience, many of them elderly nycha residents living with the not-unreasonable fear that their public-housing homes will soon be torn down to put up exactly the sort of urban renewal Weiner was touting, sat on their hands. Sharpton, who had warmed up the crowd declaring “everyone is entitled to a second chance,” was miffed about Weiner’s wet-blanket performance. “I set it up for him. Then he puts everyone to sleep,” the Rev groused. “Don’t want to say it, but Weiner blew it.”

As I watched him make the rounds, it was easy to wonder why he was even bothering, if he wanted to be mayor at all. As the other candidates sat like good little students, eyes forward, hands clasped, Weiner was a Ritalin prescription waiting to be written, fidgeting, covering his face with his hands, off in his own private Idaho. At the Kirkland & Ellis forum, in an incident that would come to be called “Slouchgate,” journalists tweeted how the former congressman looked “bored.” Weiner, monitoring the real-time feed from his spot on the dais, later complained, “Hey, stop breaking my chops, will ya?”

It was only when he was talking about himself that the candidate appeared fully engaged. For the most part, the sexting scandal has remained the hairy elephant in the room, invoked more often than not by Weiner himself. On a downtown street, a woman wanted to take a picture with the congressman. She put her arm around him but quickly removed it. “Oh,” Weiner joked, in apparent reference to his assumed unsavoriness, “you want to get close, but not that close.”

At a stop at the New Kings Democrats club, however, the issue came to the surface. Chris Owens, a well-known community organizer, asked, “I have a three-word question for you: How dare you?” Saying he was a parent with two sons, Owens told Weiner he was not only “outraged and disgusted by what you did but also by the fact that you have the arrogance to run for mayor now.” Weiner first attempted to slide past this, but then met it head on. “Look. I’m going to win this election, okay?” Weiner said. “I’m going to govern this city really well. I’m going to do it based on a foundation of Democratic ideals, and I’m going to do it on a foundation of progressive values, and I’m going to do it smart … all right? And let me tell you something, if you don’t like me, don’t vote for me … okay?” Nothing I’d heard Weiner say during the campaign carried the same conviction.

Whatever his troubles in the forums, Weiner’s gift for nitty-gritty day-to-day retail politics remained manifest. Buttonholing subway riders, commanding his aides to look up whether Oscar or Felix said a particular line in The Odd Couple, wading into a jam-packed crowd of black hats at a rebbe’s wedding (he called it “yidlock”), is what Anthony Weiner was put on this Earth to do. The man is a natural. Never happier than with a bullhorn in his hand, Weiner walked through the Brooklyn LGBT Pride Parade in skinny orange-y chinos (“How I roll!”) offering shout-outs to dozens of people hanging out of windows just to get a glimpse of him. Near the end of the parade, a few drunken revelers started chanting, “Everyone deserves a second chance.” It mattered not at all that a middle-aged woman kept shouting, “We need a grown-up!” A skinny man with a very thick skin, Weiner took it all in stride, reveling in the grand tableau of American democracy at work.

Still, even after a twenty-year career during which he was often characterized as a political Sammy Glick, you had to wonder whether the stated goal—Mayor Weiner, actually doing the job—was really what mattered most to the candidate. Cynics suggested he was only in the race because his pre-scandal war chest—much of it donated by the right-wing ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in favor of his superhawk pro-Israel position—was burning a hole in his pocket. Then there was the hoary “redemption” theme, the conventional wisdom that Weiner had willed himself into the race for no other reason but to “clear his name.” In the run-up to his announcement, Weiner had been telling people that he couldn’t stand the idea of his young son growing up to read that the scandal was the last thing his father had ever done in politics.

There were less charitable analyses. Sal Albanese, a long-shot mayoral hopeful who’d spent fifteen years in the City Council, much of it serving with Weiner, said, “If I did what Tony did, I’d go hide on a mountain. I’d become a hermit. Work in a soup kitchen, anything. I wouldn’t run for mayor. Only Tony Weiner would think, Oh, I got it, I’ll run for mayor! He has no shame … I’m no psychiatrist, but there’s something fundamentally wrong there.”

It was not an uncommon opinion heard around town, that Weiner was somehow crazy, a variety of “narcissist,” “opportunist,” and/or “sociopath,” his decision to run for mayor having sprung from the same dark exhibitionist place in his soul that caused him to send half-naked self-portraits to blackjack dealers in Las Vegas.

The kicker in this was, of course, that it seemed to be working. Apparently doomed to single digits, he astoundingly kept moving ahead; he was neck and neck with the teetering Quinn, outpacing Thompson and the rest. “Name recognition” was cited as his strong suit. It was a perfect modern irony: The sexting episode, the candidate’s self-described “worst moment,” the spectacular crash and burn that had supposedly buried him, had become the enabling vehicle of his increasingly storied comeback. The sheer rubberneck stretch of his unwholesome celebrity had granted him an ever-blossoming bouquet of press, while his opponents, Quinn included, were left to battle over a few lonely notebooks.

Riding through a rainstorm on the way to a mayoral forum on the southern shore of Staten Island, Weiner had clearly grown weary with such talk. “For two years, people have been telling me, with 100 percent assurance, what I should do,” the candidate said. “ ‘You should stay dark for five years, you should go form a coffee commune in Mexico and change your name.’ What I’m doing right now feels right to me. It is what I do, what I’ve always done: running for office, doing public service. I want to win, and I think I’ve got ideas that no one else does. Why is that so difficult to believe?

“Maybe the scandal thing does give me an opportunity to get stuff heard. [It is] always good when people are listening,” he said, “but it’s not worth the pain I put people through.”

On the contrary, the ex-congressman remarked, if he was getting traction in the race, it was due to the fact that he was “running an independent campaign and talking about ideas,” policy initiatives like No. 29 of his 64 “Keys to the City,” i.e., “Create Single Payer Laboratory in New York City.” Building on his crowd-pleasing holdout support of the “public option” during the debate over Obamacare, Weiner has been giving PowerPoint presentations around the municipality, noting that even as city medical costs exceed $12 billion—17 percent of the budget—1.2 million New Yorkers remain without basic coverage. Single-payer would save billions. People who said it wouldn’t work were victims of what Weiner called “learned inertia … Everyone said you can never get crime down, but it turned out that you can. They said you couldn’t run the city, but you can.” Single-payer would be the same thing, Weiner said. All it took was “creativity, hard work, and electing the right mayor.”

Right then, Weiner’s SUV splashed through a two-foot-deep puddle on the wide boulevard named for John F. Hylan, the 96th mayor of the City of New York (1918–1925). During Hurricane Sandy, this area took heavy damage. People were without power for weeks. Even though Weiner claims to have “never, not for a single day,” missed being in Congress since his resignation, Sandy was an exception. “The storm pretty much fell right on my district” in Brooklyn and Queens, he said mournfully. If he had been in Congress, then he might have been able to help. It was a regret Weiner said he’d “live with” for a long time.

“I know a lot of people think me running is some form of therapy,” Weiner finally said, watching a great plume of water fly by his passenger-seat window. “There might be some truth to that. But I’d like to know what part of this is supposed to be therapeutic.”

At a mayoral forum held at the Gil Hodges Public School in Flatbush, where government meddling into ritual circumcision was a hot issue, the moderator asked the candidates which New York mayor they most admired. Thompson, Quinn, and De Blasio played it safe, invoking the hallowed if distant memory of Fiorello La Guardia. Weiner was alone in choosing Ed Koch. As a model for a prospective Weiner mayoralty, that sounded about right, with slightly better jokes, reggae music, and maybe a smidgen of Giuliani heavy-handedness thrown in. For sure, the velvet-fist serenity of Bloombergian noblesse oblige/nanny state would be a thing of the past, as Weinerworld would almost be guaranteed to be a noisy junkyard dog of a place. “I’m looking for miserable City Council people, unions threatening to strike, and lots of Sunday press conferences,” said one City Hall reporter. Another said, “It won’t be boring, which is good for us, but maybe not so good for the rest of the city.”

Even excluding the moral-turpitude angle, there were still plenty of good reasons not to vote for Anthony Weiner. How was a famously non-delegating micromanager, someone who has never presided over anything larger than the office of a junior congressman, to ride herd on 400,000 city workers, many of whom were looking to even the score after the Bloomberg cold shoulder? Could the impulsive Weiner keep a poker face sitting across the table from the JPMorgan Chases and MetLifes of the world?

Short of pledging not to retain Ray Kelly, the hot-button police commissioner, the candidate has provided little insight into the inner workings of his prospective administration. Reasoning that his “life particulars are not likely to be referenced in political textbooks,” Weiner has eschewed the usual consultant route, choosing instead to essentially run his own campaign. This may change by the runoff, which Weiner sees as “me and Quinn,” but right now he’s enthralled by what he calls “my independence,” his ability to call his own shots, be wholly his own best counsel.

Weiner and I were discussing why in the world I would vote for a guy like him just because he was fun to hang around with in a Queens kind of way. His retreat from the 2009 post-term-limits election simply because Bloomberg had $20 million trained on his skinny body wasn’t exactly a profile in courage. The candidate was defending himself when his phone rang.

After a brief conversation, Weiner said, “You want to meet Huma?”

In the Times Magazine article, Weiner describes the first time he noticed Huma Abedin, then working as the “body person” for First Lady Hillary Clinton. “I was like ‘Wow, who is that?’ … She’s like this intriguing, fascinating creature.” At the time, the comment seemed on the creepy side. But now, as Huma entered the coffee shop, it was blazingly obvious what Weiner meant.

She approached in a knit white top and navy-blue business skirt, her dark, almost black hair down to her shoulders. She wore bright-red lipstick, which gave her lips a 3-D look, her brown eyes were pools of empathy evolved through a thousand generations of what was good and decent in the history of the human race. The harsh, cheap buck lighting in the coffee shop couldn’t lay a glove on her. By the time she sat down, the harmony of angels had vanquished the tinny background music from every corporate space on the planet. Of course, you’d seen pictures before. But you’d also seen pictures of the Taj Mahal. It didn’t quite come up to actually being there.

“Hi,” she said graciously, before turning to give Weiner a peck on the cheek. The couple engaged in some small talk; they like to discuss each other’s day, their scheduling. Then she left. Weiner watched her go and then returned to what he was talking about, boilerplate polspeak about how great a mayor he was going to be, the way he was going to put a Kindle in every child’s backpack, and how he didn’t think charter schools should pay rent when co-located in public-school buildings. Something like that.

A few days later, I saw Huma again, this time in the couple’s apartment, a nifty, reportedly $3.3 million spread owned by a longtime backer of the Clintons. This was the so-called domestic segment of the reporting process, a quick sitting with the modern young couple and their 18-month-old son. There were to be no searing re-creations of the sexting scandal, no intrusive inquiries about personal lives. Huma was a famously private person, give or take a Vogue spread or two, and wanted to keep it that way. It being Saturday morning, the young family was in relaxation mode, Weiner in his customary ball cap and shorts, Huma in new jeans and a cool striped summer shirt. She wore no lipstick, little makeup at all.

When Huma brought over some cookies and a cup of coffee, Weiner told her not to say how much the flat little things cost per pound. “He’ll just write how rich we are,” he remarked. After a decade in a Forest Hills bachelor pad, the plush surroundings were an issue for the man who couldn’t get through a half-hour without claiming to be the champion of “the middle class and those struggling to make it.” His present circumstances mattered little, Weiner contended; when he put his head on his pillow at night, he didn’t “think about the skyline of Manhattan” but rather “this iconic view of a stoop in Brooklyn and the elementary schools,” the P.S. 39 world in which he’d grown up. The middle class was as much a symbol as a reality. It was “an aspirational thing,” the candidate explained.

Jordan, a natty little fellow with a passion for fedora hats, had “locked an eleven o’clock nap,” as his father called it. So, treading lightly, I asked Huma how she might approach being First Lady of New York. Starting as an intern in 1996 during Hillary’s First Lady days, Huma certainly knew the territory.

“Huma will be a kickass First Lady,” Weiner threw in, adding that the position has “been vacant for a long time.” With the Bloomberg period, Giuliani announcing his pending divorce at a press conference (without telling Donna Hanover first), and Bess Myerson, America’s first Jewish Miss America, in the role of Ed Koch’s supposed paramour, traditional New York City First Ladies had been few and far between in the past half-century. Asked if she planned to move into Gracie Mansion should Weiner be elected, Huma said, “I really haven’t thought about it. I guess I am going to have to start.”

As the conversation turned to kids and travel, Huma showed me a picture of her father, Syed Zainul Abedin, which she keeps in a small frame on the windowsill. Born in India in 1928, Syed Zainul Abedin was educated at the Aligarh Muslim University, in a western Uttar Pradesh town where, in 1803, a regiment under the command of the British East India Company waged war against the Maratha Empire. With rimless glasses and a large shock of hair swept across his forehead, Syed Zainul had the look of a young threadbare scholar, which is basically what he was, Huma said. This was how she came to be born in the notably unexotic locale of Kalamazoo, Michigan, during her father’s brief tenure at Western Michigan University. Two years later, the family moved to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she grew up.

“My father had that perfect-British-education thing. He had a system of what I was supposed to read and in what order,” Huma said, walking across the room to a large bookcase and pulling out a softcover copy of Anna Karenina. At the corner of the first page was written “L6.” That meant, Huma said, “level six … I was supposed to go through the levels. Silas Marner was level one.” She pulled out two more volumes, The Count of Monte Cristo, marked “L15,” and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, “L19.”

Perhaps it was seeing those books, to have had that tiny portion of her life revealed, that caused the “domestic visit” to suddenly take on an air of narrative intensity.

It brought you right back to that senior-citizen center in Gravesend, to that gruesome scene when Weiner announced his resignation a little more than two years ago. For anyone who cared even a little for Anthony Weiner and human decency in general, it was a break that Huma wasn’t standing beside him when that lunatic from The Howard Stern Show started screaming, “Senator Weiner! The people demand to know: Were you fully erect?” At the time, Huma and Weiner had been married for a year, but they’d never spent more than two weeks together at any stretch. She was pregnant with his child but couldn’t have known his secrets, not all of them.

Weiner says he wouldn’t have entered the mayor’s race unless it was okay with Huma. As it turned out, he said gleefully, “She sometimes seems more into it than me.” Scheduled to host “a ladies’ tea fund-raiser,” Huma nonetheless tried to downplay her role in the campaign. Even deciding to participate in the confessional Times Magazine story that signaled the comeback’s start had been difficult for her, she said. But then again, she added, a quick whiff of Realpolitik entering the conversation, “Well, we didn’t have much choice with that, did we?”

If it was a mystery why Huma Abedin decided Anthony Weiner was the man for her, there were clear practical reasons to stay with him. It was far more than the fact that she worked for Hillary, learned the haute Tammy Wynette drill from the best. Weiner was, after all, the father of her child. If the candidate didn’t want Jordan to grow up hearing how the naughty pictures had ended his father’s political career, why should his mother feel any differently? Then again, they could just love each other.

Across the room, checking his BlackBerry, probably thinking about whether he was going to play hockey that night, Anthony Weiner began to take on the aspect of a very lucky man. How insane, how self-destructive, must he have been to have risked losing a life with this woman? Only someone who felt down deep that he didn’t deserve such good fortune would have pulled something so twisted and dumb. But what marvelous relief it must have been to stare into Huma’s eyes and feel forgiven. You could get drunk on such forgiveness. For all the endless talk of Weiner’s narcissism, it was easy to see the mayor’s race a whole other way: He was doing it for her. If Huma was willing to forgive him, what choice would the voters have but to do likewise? The entire Anthony Weiner–for–mayor project might turn out to be a winner or a loser; it might be nothing more than a mutually-agreed-upon delusion, but the two of them were in it together. If there really was a reason to vote for Weiner, this seemed to be it.

With the campaign rolling around, the candidate was saying now that the electorate was “prepared to give me a second chance. I’ve got to prove myself.” His only misgiving was that, with the time demands of the mayoral race, he would miss the quiet days of his exile, chilling with Jordan, feeling connected to the procreative chain of being.

Weiner pondered the idea for a moment, then he shouted, “Huma? Hey, honey? Huma! Was I happy before I started running for mayor?”

There was no answer. Huma was in another room, out of earshot. Weiner repeated the question. “Huma? Honey?”

When Huma came back into the living room, she said, “Oh, God, yes. You were happy.”

“Would you say I’m less happy now that I’m running for mayor? You know, much less happy or slightly less happy?”

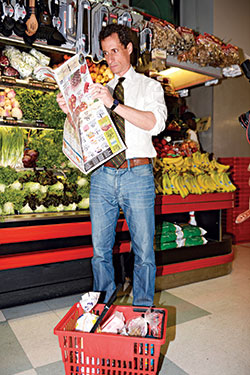

Huma looked at Weiner with bemusement. It was quite possible that she was the most cosmopolitan human being on Earth. Compared to her, he was an outer-borough schmoe, the guy who ran for student government at SUNY-Plattsburgh with the slogan “Weiner’s on a Roll!” The other day, to dramatize No. 12 through No. 16 of his “Keys to the City” idea book, which dealt with “hunger,” he decided to go on a “food-stamp diet,” attempting to get by on $1.48 per meal. Except Weiner had no clue how a food-stamp recipient might spend his meager funds. He led a trail of reporters to an upscale supermarket and stood in the middle of an aisle with a red plastic basket looking nonplussed. “Potatoes! They’re cheap,” he finally said and scurried off to secure a five-pound bag.

Weiner was a pol, with every bit of the cheesy hustle that implied. But Huma knew that. She’d seen it before. Then again, after all that perfect British education and using the right fork at state dinners, maybe that was what she liked about him.

“What do you want me to say, honey?” Huma asked. “That you’re happier or not happier?”

“I don’t want you to say anything. I just want your honest opinion.”

“Okay,” Huma said. “I would say, on the whole, you are slightly less happy since you started running for mayor.”

“Thank you, Huma!” Weiner declared.

Before I took off, Weiner said there was one thing that hadn’t changed since the beginning of the narrative that had consumed his life over the past two years. He still felt like a character in a movie. He found this kind of liberating, going along with the flow, “free from trying to manage the torque of the tide.”

“What kind of movie?” I asked. “A Fellini movie?”

“No,” Weiner said. “Not like that. … It’s more like—who’s the Blue Velvet guy? David Lynch! A David Lynch movie. More like that.”

On the eve of the Fourth of July, Anthony Weiner, a front-runner for the moment, stood on the steps of City Hall to announce a “Declaration of Independence from Albany and a New York City Bill of Rights,” a document he’d based on ideas Nos. 25, 26, 27, 28, and 31 of his “Keys to the City” booklet. Why should some yokel from “Skinnyapolis” be telling New Yorkers how to run their business? It was time to make permanent the city’s control over public schools, to give the city the right to raise and lower its own taxes.

It was a little peek into one possible future, a world where Mayor Anthony Weiner would not be cowed from tweaking the tale of Governor Andrew Cuomo, who, after all, was quoted as saying “Shame on us: If Weiner were to win the election.” Toss Comptroller Eliot Spitzer into that brew, and a $20 billion seawall won’t be enough to hold back the sea of testosterone.

Weiner’s narrative had already taken him to the steps of power. It was no great stretch to imagine it would push him another 100 yards or so, into the chair currently occupied by Mike Bloomberg. One day deeper into his David Lynch movie, it was impossible to rule anything out.