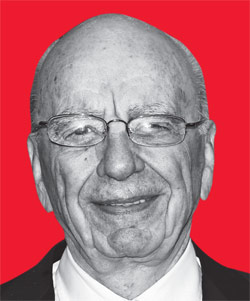

Five years ago, Colin Myler, now the editor of the Daily News, received a message from Rupert Murdoch’s people. At the time, Myler, a square-faced Brit, was a top editor at Murdoch’s Post. Now the bosses at News Corp. had an even better job in mind: Would Myler like to run Murdoch’s storied British weekly, News of the World, the largest-circulation paper in England? It was a plum job, the top of the English tabloid heap, but the offer came with a catch.

News of the World was at the lowest point in its illustrious 163-year history, in the early stages of a phone-hacking scandal that’s come to threaten Murdoch’s empire. Part of Myler’s brief as editor would be to clean up the mess or, in the euphemistic version of his paymasters, “to ensure that any previous misconduct was identified and acted upon.” Myler didn’t relish this Augean Stables part of his new job. “I felt that there could have been bombs under the newsroom floor,” he later said, “and I didn’t know where they were, and I didn’t know when they were going to go off.”

Still, for someone who’d been a Fleet Street editor for almost two decades, it was an irresistible offer, a chance to return to the British major leagues.

Myler excitedly phoned his mother, who lives a few miles from his English home in Kent. “If there was something you wanted, Mum, what would it be?”

“For you to come home,” she said without hesitation.

“Well, I’m coming,” he told her.

Now Colin Myler has returned to New York—to head the city’s other tabloid, the one Murdoch doesn’t own. Myler has come back with the deepest possible knowledge of his competitors at the New York Post, as well as ample reason to hold a grudge against its owner, Rupert Murdoch, who, it seems to many, was happy to let Myler take heat for the phone-hacking scandal in order to protect his own son. Myler has returned with a tarnished résumé. The scandal continues to threaten his reputation. Last week, a member of Parliament accused Myler of authorizing his reporters to dig up dirt on M.P.’s investigating News of the World. But New York is a new beginning. He’s no longer marching to Murdoch’s orders. Now he can put his own ideological stamp on the Daily News, score-settling of a different kind. For Colin Myler, these intertwining pasts are a prologue to the tabloid war he’s now joining. “It’s going to be fun,” Myler told a reporter.

The fun is going to be in competing against a man who first saved his career, then nearly ruined it. When Rupert Murdoch brought Myler to the Post, in late 2001, the move was a step down. For a decade, he’d been editor-in-chief of one British tabloid or another, most recently the Sunday Mirror, playing the Fleet Street game with brio. But then he crossed a line. In April 2001, in the midst of the trial of two soccer players accused of assaulting a Pakistani fan, Myler published an article that suggested racism as a possible motive. The problem was that the judge had prohibited consideration of a racial motive, and in England there are strict laws about honoring such prohibitions—“Journalism 101,” says one of Myler’s Fleet Street colleagues. The judge in the case immediately called for a retrial, and even though Myler had consulted company lawyers, he was pushed out in disgrace.

And that’s when Murdoch’s people came calling. “Rupert has always been a great rescuer,” says a former British colleague. Myler was thankful for the chance. “The Post,” another colleague says, “was a shot at redemption.”

At the Post, Myler was second in command to Col Allan, a longtime Murdoch editor who’d been imported from Australia to bring some juice to the paper and was already succeeding. Allan and Myler share a deep love for tabloid-making—neither graduated from college—but in others ways, they were very different. Allan is a fiery, sharp-tongued, counterpunching conservative. He’s soft around the middle, and his hair has grayed. Myler at the time was shaggy-headed and fit, a rugby-loving working-class kid with a charming manner, a gentle Liverpool accent, an oddly formal bearing, and an upbringing in the Labour Party—anathema to the politics of the Post.

For Myler, there was considerable pride to swallow—not to mention personal politics—and he swallowed it. “Around Col, he suppressed his ego because he had to,” said a fellow journalist who knew him well. There were benefits, though. Allan welcomed him into the Murdoch tribe. They became best mates, visiting each other’s houses, drinking together, and even engaging in the occasional brawl. Once, at Elaine’s, Lloyd Grove, a former Daily News writer, made the mistake of defending the News. “Myler told me I was a cheeky boy,” Grove says. He smacked Grove’s ear with the flat of his hand. “My ears rang afterward,” Grove says.

At the Post’s morning meeting, the two worked in a ritualized good-cop-bad-cop routine—though, in truth, both cops were pretty tough. Myler played setup man, posing sharp questions: Where’s the fun stuff? Why is there so much crime? Allan at times seemed inattentive, paging through the day’s newspapers, until something said by one of his editors set him off. Then he attacked, savaging the offender. “He was biting and sarcastic,” says a former Post editor. “He threw people out of the meeting all the time. You just get up and leave.”

It was Myler’s job to salve the hurt feelings. The task suited him. His diplomatic skills were well honed, the result of decades spent operating in large companies. “He can be quite cunning,” a colleague says. And at the Post, he filled a definite need. “Some of Col’s shit is so unreasonable, so insane, and there was no way to discuss anything with him. We would go to Myler,” says a onetime colleague. “ ‘I get it. Let me go to Col,’ he’d say.”

Myler thrived at the Post. Still, a few years into his tenure, he began to feel warehoused. To newsroom observers, he didn’t seem to have all that much responsibility. Allan set the mission, and Jesse Angelo, the then–metro editor, executed. Myler wasn’t a complainer, but privately he chafed at his role. “He certainly felt that his place was not as a No. 2,” says a person who spoke to him in New York. Myler’s wife, who’d decorated their Central Park South apartment in the style of a British country house, made the point more forcefully. “My husband is a Fleet Street editor, you know,” she pointed out.

Then, as 2007 arrived, Myler’s fortunes changed again. The year before, News of the World reporter Clive Goodman had admitted hacking into the voice-mails of the royal household and publishing stories based on the information. Goodman was eventually sentenced to four months in prison. In January 2007, the editor of News of the World, Andy Coulson, resigned, taking responsibility while claiming he knew nothing about the crimes. With Coulson gone, Murdoch needed a new editor, and there, waiting in the bull pen, was Colin Myler, well versed in the ways of Fleet Street, untainted by the scandal, and a News Corp. soldier of proven loyalty—“He owed Rupert his career,” says a journalist who knew him well. For Murdoch, he was, as several people later said, “a safe pair of hands.”

Myler arrived at News of the World in January 2007 and found that the phone-hacking scandal was only one of the tabloid’s problems. Circulation was dropping, advertisers were restless, and the newsroom was a boys’ club—“very loutish, very laddish,” Myler said in testimony to the Leveson Inquiry, established by the prime minister to investigate the scandal. To get the paper back on track, he promoted women, put ethical controls in place, and set in motion ambitious plans to broaden the target audience, launching an upscale women’s magazine and expanding political and foreign reporting. He didn’t abandon the traditional working-class reader—indeed, Myler believes a tabloid’s job is to advocate for this constituency. “The only people standing between the readers and the bullshit of marketers and politicians is the journalist,” one of his editors explains.

Of course, social conscience doesn’t sell papers. For that, Myler knew, you need scandals, and he pursued them with a passion, spending heavily to get the story. “There’s a duality in his nature,” says a colleague. “In person, he’s nice, warm, decent. In the newsroom, he puts that aside and goes after whatever the sensational story is.” About a dozen years earlier, Myler had been blooded in national scandal when, as editor of the Sunday Mirror, he was approached by an enterprising London gym owner peddling secret photos of Princess Di working out in a leotard—he’d planted a camera in the wall. Myler’s company reportedly paid £100,000 for the photos. The story was denounced by the government, the royal family, and even parts of the press—but the paper flew off the newsstand, which was the point.

At News of the World, Myler’s go-to guy for scandal was his investigations editor, a man named Mazher Mahmood, whose sobriquet was “the fake sheik” (in Britain, sheik rhymes with fake). Mahmood’s specialty was the disguise; his most famous one was of a wealthy Arab businessman. Myler sent the sheik in pursuit of Fergie, the cash-strapped Duchess of York, who promised access to her former husband, Prince Andrew, after Mahmood brandished a valise full of cash (fergie ‘sells’ andy for £500k was Myler’s headline). In another sting, the sheik delivered £150,000 in cash to a person who claimed he could fix cricket matches. The story earned News of the World an award for “scoop of the year.”

Pursuing scandal didn’t always go so well. Myler authorized a £25,000 payment to a dominatrix to film an S&M orgy featuring foreign-looking military uniforms. The organizer was Max Mosley, an Oxford grad and the son of a famed Nazi sympathizer, who oversaw Formula One racing in Europe. Myler, a former altar boy who said he was offended by Mosley’s depraved behavior, ran the resulting story under the headline F1 BOSS HAS SICK NAZI ORGY WITH FIVE HOOKERS.

Mosley sued, admitting a passion for S&M but denying an affection for Nazis. The court awarded him £60,000, which humiliated Myler but didn’t seem to bother Murdoch one iota, possibly because Murdoch needed Myler more than ever to quell the growing hacking scandal.

When Goodman was released from prison in early 2007, he immediately contacted newspaper executives and told them he expected to be rehired as a reporter. “It was quite an extraordinary and surreal experience,” Myler later testified. The ex-con claimed that he’d been promised his job back if he didn’t implicate anyone else. Goodman said he knew others who’d participated in or known about hacking at News of the World. He said he was planning to pursue an appeal—which might have led to his allegations’ becoming public.

News International, News Corp.’s British newspaper division, had claimed that Goodman was a “rogue” reporter, a lone operator who worked with a private investigator and no one else. And Myler himself had defended that story in an official hearing. On February 22, 2007, he’d answered questions for the Press Complaints Commission. Phone hacking, he told the commission, was “an exceptional and unhappy event in the 163-year history of the News of the World involving one journalist.”

After Goodman’s reappearance, the task of investigating his charges fell to Myler. Privately, he resented being tossed into this bizarre affair. “It was a case that I inherited,” he said in testimony. Still, he wasn’t one to shirk his duty, and he quizzed the people named by Goodman. “[I] talked to them about the allegations, and they denied every single one of them,” Myler later testified.

Goodman didn’t get his reporter’s job back, but he did receive compensation—£243,000. Myler later told a committee that he hadn’t known about a payment, though another executive told the same committee that Myler had known.

Then, in the spring of 2008, the scandal erupted again, this time with even more violence. Gordon Taylor, head of the Professional Footballers’ Association, threatened to sue a division of News International, claiming his phone had been hacked. He went further: “What happened to him is/was rife throughout the organisation,” his attorney told a legal adviser for News International. Taylor had obtained a copy of an e-mail, dated June 29, 2005, that contained transcripts of 35 voice messages left on Taylor’s phone. The e-mail was addressed to Neville Thurlbeck, News of the World’s chief reporter. (Thurlbeck denied receiving the e-mail.)

Myler was made aware of the “for Neville” e-mail in May 2008, and the significance struck him immediately. “[The rogue-reporter defense] couldn’t be correct,” he later acknowledged to the Leveson Inquiry.

Myler pushed the matter up the chain of command. “Responsibility regarding the corporate governance of a company goes beyond my pay grade,” he later noted. On June 7, 2008, he forwarded the troubling news to James Murdoch, Rupert’s son and the chairman of News Corp. Europe and Asia, which oversees News International.

“It is as bad as we feared,” he wrote to James, referring to Taylor’s vindictiveness. Taylor wanted the paper “to suffer” or he wanted to be “made rich.” He was demanding seven figures “to keep the matter confidential,” according to one account.

For Myler, James wasn’t an ideal person to be in a foxhole with. “They were like alien life-forms,” said a veteran Fleet Street editor. James doesn’t care about newspapers, which don’t make the company much money. He considers himself a numbers-driven, unsentimental modern executive. “James would be at a meeting with editors, and he’d talk about ‘direct transactional relationships’ with ‘customers,’ not ‘readers,’ ” recounts a journalist. To Myler, James spoke a foreign language. “He came into a party sighing, ‘Oh, I just met with James for an hour, and I have no idea what he was saying,’ ” reported a fellow editor.

But on June 10, 2008, Myler and James huddled together in James’s office to decide the fate of the Taylor case. Tom Crone, the paper’s lawyer, joined them. What was clear to everyone was that it would be best if Taylor’s lawsuit disappeared. For James, too, phone hacking was a problem created by others—he’d been in charge of the newspapers for only six months at the time. “Nobody was very keen on [a trial],” Myler testified. Myler, like others, insisted that the suit was a business matter. “[Newspapers] deal with very complex and significant negotiations throughout the course of their business very regularly,” Myler testified. News International agreed to pay Taylor roughly £700,000, an extraordinary sum, in Myler’s view—after all, the paper hadn’t published a story using the phone messages. Myler had another concern—he’s a newsman who trades in secrets for a living, so he knew better than anyone that anything, even a secret settlement, can become public.

And it did. On July 8, 2009, The Guardian published a story with the headline revealed: MURDOCH’S £1M BILL FOR HIDING DIRTY TRICKS. The Guardian outlined the Gordon Taylor settlement in embarrassing detail, but it went further: The paper quoted sources saying that thousands of phones had been hacked, the implication of which was that phone hacking extended well beyond one reporter.

The story was explosive, and in the summer of 2009, Myler answered questions to the Press Complaints Commission and appeared before a parliamentary committee. At the committee hearing, Myler was in his usual smart executive look: suit, white shirt, and blue tie—“He scrubs up well,” says an editor who worked with him. With his shopkeeper’s features and North England accent, Myler often strikes people as guileless. That day, he turned in an artful performance. He didn’t deny the existence of the damaging “for Neville” e-mail, but he pivoted, going on the attack. He explained that he’d personally investigated the allegations, and told the panel that “no evidence was found [of a wider scandal].” Neither, he noted, could News International’s lawyers or the police, who had swiftly questioned The Guardian’s allegations. At the hearing, Myler seemed exasperated, at times almost contemptuous. “I have never worked or been associated with a newspaper that has been so forensically examined,” he said. In an editorial, Myler’s paper accused The Guardian of “deliberately misleading” the British public.

Later that year, the Press Complaints Commission sided with Myler, asserting that there was no evidence to corroborate The Guardian’s story. But The Guardian persisted, and two years later, on July 4, 2011, it published another explosive story. News of the World had hacked the voice-mail of missing 13-year-old Milly Dowler while police were searching for her. Her despairing family knew messages on her cell phone had been deleted, which had given them hope that she was still alive, when in all likelihood she was already dead.

To the British public, hacking the royal family was naughty, but the royals had long been a national soap opera and so were fair game. Taking advantage of the grief-stricken parents of a teenage girl was another matter. The story reignited the scandal. Murdoch, who owned 40 percent of the British newspaper market, had long been the single most influential person in British political society, cowing politicians who feared retribution. After the Dowler story, politicians sensed weakness. M.P.’s rose up, calling for an investigation, as did Prime Minister David Cameron, who later admitted he’d gotten too close to Murdoch and media proprietors.

In the executive offices of News Corp., panic set in. The scandal wasn’t just bad public relations. It was damaging business, always Murdoch’s principal concern. A deal for News Corp. to gain complete control of BSkyB, the largest pay-TV company in the country, was soon scuttled. Bold action was called for. On July 7, 2011, three days after the Dowler article, Myler was summoned from the second-floor newsroom to the tenth-floor executive offices, where he met with Rebekah Brooks, a Murdoch favorite and chief executive of the newspaper division. She informed Myler that damage control was the order of the day. A decision had been made: News of the World was to be closed after the next issue.

“Colin had no idea it was coming,” recalls a former colleague. He was furious. The alleged crime had occurred years before—the Milly Dowler case dated from 2002—but now he and some 200 journalists were to be tossed out of work, their reputations tainted, their futures uncertain. On July 9, 2011, the day the staff put the last issue to bed, Myler climbed atop a table in a large, wide newsroom as journalists gathered around. Myler was a dignified, respected, but distant editor. Now he seemed emotional, channeling the indignation of his troops.

“Not your fault, boss,” someone shouted.

“You are the best professionals I’ve ever worked with,” he told them.

Shuttering the paper did little to halt the scandal. The dominoes kept falling. Myler’s chief reporter Neville Thurlbeck and his former news editor, Ian Edmondson, had been arrested in April. And the investigation began to target higher-ups. Coulson, the editor before Myler, was arrested on July 8, Rebekah Brooks on July 17.

Then, on November 10, James Murdoch was called before a select committee of Parliament and asked if the huge payment to Gordon Taylor had been designed to purchase his silence about a wider hacking scandal. James claimed he was merely following the advice of lawyers and of Myler. He’d never even looked at the damaging “for Neville” e-mail, he claimed. “If [Myler] had known that there was wider-spread criminality, I think he should have told me,” James said. “We have to rely on these people, and we have to trust them.” Later James added that Myler had concealed important information from him.

Myler was angry. He’d done everything asked of him, even participating in what he later agreed could be perceived as “a cover-up.” And through it all, he’d put out a superior newspaper. Now apparently he was supposed to “be the bunny,” as one colleague put it.

On July 21, with the press circling, Myler and Crone conferred. James’s assertion in his testimony “was very damaging to our reputation,” Crone says. “We were going to get crucified. One has an obligation to the truth and to self-preservation.” Later that day, Myler and Crone issued a brief, carefully worded statement. James was “mistaken,” it said. They had warned James about the “for Neville” e-mail, which indicated a wider phone-hacking problem. “As far as I am concerned, there was no ambiguity,” Myler told the committee on September 6. The goal of their statement, they claimed, was merely to correct the record. But the significance was clear to them: They were calling James a liar. “We knew we were challenging the executive chairman … That’s inevitably going to be serious,” says Crone.

On December 15, 2011, five months after the paper closed, Myler was called before the Leveson Inquiry. In earlier appearances he’d gone to war for Murdoch, but this time his allegiances had changed. He’d gone a bit gray; he looked tired. When a government lawyer pointed out that his 2009 testimony to the Press Complaints Commission had been “disingenuous,” Myler didn’t disagree. “I had no reason not to give them a full and frank answer,” Myler said. “For that I apologize.”

Then the chairman of the inquiry, Lord Justice Leveson, quizzed him. Myler had argued that settling the Taylor lawsuit was a simple strategy to “limit reputational damage.”

“What one person might describe as a cover-up, another person would describe as an attempt to limit reputational damage?” said Leveson.

“Absolutely, sir,” said Myler.

Myler was not the only one who felt betrayed. “When people are shooting at you, you keep your head down. You stand together,” Col Allan said to an old friend. “Colin panicked to save his own reputation.”

Allan had a word for Myler’s behavior: “Weak.”

Myler had spent three months out of work when another savior appeared: Murdoch’s Manhattan rival, real-estate magnate Mort Zuckerman, owner of the Daily News. Like Murdoch, Zuckerman is a lifelong newspaper junkie. Like Murdoch, his fortune comes from elsewhere. “Wisely, I didn’t go into publishing to make a living,” he says.

The Daily News has not exactly brought him journalistic glamour, either. In Zuckerman’s circles on the Upper East Side or in the Hamptons, it’s the Post that animates dinner-party conversation. Zuckerman told me that his proudest accomplishments with the paper were to help elect Rudy Giuliani and then Michael Bloomberg to their first terms—impressive feats, to be sure, but not exactly recent ones.

Zuckerman has constantly juggled the names at the top of the masthead, employing two new editors in the past two years. Last fall, he was searching yet again, this time to replace the Boston newsman who’d taken over just a year earlier. (“How many saviors does he get?” Allan quipped to a colleague.) Zuckerman turned to Britain. “Mort believes that the British are the only people who know how to do tabloid journalism,” says one of his advisers. Zuckerman summoned Myler to a meeting.

At the time, Myler was cooling his heels at home in Kent, spending time with his family and brooding. He visited his new grandson, stopped by his mother’s for tea, and wondered if he’d ever work again. In Britain, he was seen as damaged goods, says a fellow journalist. Yes, he’d stood up to the Murdochs, but he’d also admitted that he hadn’t been entirely frank in the past. “No one believes Colin Myler is a truth-teller,” said M.P. Tom Watson, who is helping to write the select committee’s report on the phone-hacking scandal.

Zuckerman dismissed concerns about phone hacking. “He’s not involved,” he told me categorically. In any case, Zuckerman had other priorities when he sat down with Myler. “I had a three-hour conversation with Myler about every single aspect of the newspaper business,” says Zuckerman. “It was the best three-hour conversation about a newspaper I’ve ever had. He understands detail as well as broad content. And he knows New York. You can’t find a lot of editors who can fill those criteria.”

Myler had another appealing trait. His drive to succeed more than matched Zuckerman’s—“He’s extraordinarily highly motivated,” Zuckerman crows. “The Post will have a much tougher competitor than it’s ever had in the Daily News.”

Myler was thrilled by the offer, but he hesitated to leave his family behind, especially his aging mother. But she assured him she understood. “He needed this for his self-esteem,” she told me by phone. When Myler’s appointment was announced, Allan sent Myler a message: You bastard, let the battle begin.

Myler was ready to engage. “I’m looking forward to working again, to be honest,” he said.

In the Daily News’ newsroom, with its famous four-sided clock, Myler goes coatless and still likes his afternoon cup of tea. He’s been a journalist since he quit school in his teens, and he’s probably as at home in a newsroom as anywhere. He’s already injected more punch into the paper. And he’s let the staff know that he is indeed highly motivated. He’s among the first to arrive and the last to leave.

Still, what was billed as a delicious mano a mano conflict between Myler and his former boss at the Post started off more like a tepid cup of afternoon tea. The Observer reported that the Daily News learned that on surveillance recordings, Allan had been called “a very, very good friend” of the alleged Upper East Side madam recently dominating the tabloid headlines, yet Myler declined to run a story. (Allan denies having any relationship with the alleged madam.) Surprisingly, Allan was a gentleman, too. One of Myler’s former News of the World editors said that Myler had approved the surveillance of attorneys representing alleged hacking victims, but the Post wrote nothing.

Still, Myler battled in his own way. No longer did he have to suppress his liberal leanings. Politically, the Daily News had been tracking Zuckerman’s Democrat-in-Name-Only evolution, but Myler has seemed to nudge it toward his own Labour Party leanings. WHAT DOES A WOMAN HAVE TO DO TO PROVE SHE WAS RAPED?, a front-page headline asked after a jury failed to convict a cop on rape charges. And in the Trayvon Martin case, he steered his paper’s coverage crisply leftward. He threw a jab at Murdoch’s Fox: “Fox affiliate in Florida portrayed a group of neo-Nazis as a ‘civil-rights group’ that wanted to protect white citizens in the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting,” said a headline. The paper also reached out to immigrants, whom it portrays as future Americans, sharing the dreams of every New Yorker. Myler no longer sounds like a Murdoch man. “One of the things, as an editor, you take great pride in is making a difference,” he said recently—meaning: in the lives of the less fortunate.

But scoops are what really matter. And Myler wanted every scoop. He arrived in New York in January, in the midst of a very hot story. A pregnant Beyoncé and husband Jay-Z reportedly took over an entire wing of Lenox Hill Hospital. It was perfect tabloid fodder: a beautiful, powerful couple helping themselves to more than their share. Trying to duck the cameras, Beyoncé and Jay-Z tried to sneak out of the hospital in the early morning with baby Blue Ivy. Myler gathered his editors at the usual news meeting the next day. The room is impressive—one wall is a mosaic of tiny slides of old Daily News photos, from Joe DiMaggio to Angelina Jolie—like a newsroom version of stained glass. But the atmosphere that day was anything but churchlike. He was told that the News photographer had been out of range. He grimaced and moved on. “What did the reporter get?” Myler wanted to know. No reporter had been there. “We don’t have overnight anymore,” he was told.

Which is when Myler went crazy. He didn’t raise his voice, but his tone and his intensity were “withering.” To Myler, these were excuses—the Post had put a reporter on the scene. “There’s only one big story every day, and you have to be on it,” he told them. He let them know that their job was to never, ever get beat by the Post.

Because beating Rupert Murdoch’s Post would not just mean beating Rupert Murdoch—he’d also be burying his own complicated past.

Related: Post Editor Col Allan Protests Use of Anonymous Sources