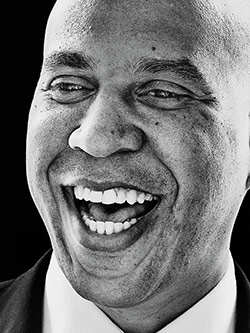

You just can’t stop Cory Booker from connecting. On the teeming concrete boardwalk in Long Branch down by the shore, the man who will almost certainly become New Jersey’s next U.S. senator—a man who’s lived with the sheen of inevitability his entire, 44-year-long life—is wearing canvas Polo shoes and a loose-fitting dark-blue linen shirt that seems vaguely Indian. It’s the Fourth of July, and he’s meeting the sunburned holiday electorate, the first mayor of Newark in decades to be promoted rather than indicted. Way ahead in the polls, and in fund-raising, Booker is on the hunt for something else: life-force-sustaining electoral tactility. His eyes search relentlessly for yours, then bug in delight and human recognition. Big smile, or, if called for, concerned frown: Tell him something serious, and he’ll turn on a dime.

He’s quick with the hugs and giddy, affirmative chitchat—oh, his good friend lives in your town, he says, and, again and again, “I’d looooove to get my picture taken with you.” Thumbs up; the iPhones shhhick their fake-shutter shhhick. Then: Share on Facebook, you and Cory at the beach. He’ll speak Spanish with you if you’re Latino, or if you have kids he’ll get down on one knee and be as bouncy and attentive as anyone from the Children’s Television Workshop. Young guys get multipart handshakes; older ones get bro-hugs; and parents usher their offspring toward him (“He could be president one day!”). Women in bikini tops and sarongs lean into Booker’s six-foot-three, onetime All-Pac-10 bulk, and every once in a while, he gives a disarming hand gesture where he appears to be grabbing a (nonexistent) set of pearls around his neck.

Ambling gawkily alongside him in shorts and NBA-logo socks is former senator Bill Bradley, the Knicks star turned neoliberal wonk and Booker’s political mentor for twenty years. Booker pulls out a handkerchief from his back pocket and daubs his sweaty bald head; it’s hot. People offer to buy them food from the booths that overlook the beach—cheesesteaks, butterfly fries, fruit shakes. Not to mention: Marine recruiters, kitchen remodelers, and a chance to pose for a picture with the old Batmobile (which Booker and Bradley did, together, an age-reversed Batman and Robin).

The funny thing is, down here you might get the idea that these SPF suburbanites are Booker’s real constituents, the people for whom he actually redeemed Newark—a terrifyingly broken-down and corrupt postindustrial city they long stayed out of but were, they want to believe now, pulling for all along. Booker is a good avatar for their fine liberal sentiments because he is also one of them, or perhaps everything they long for their kids to be. He grew up in affluent, verdant (and before his family moved there, all-white) Harrington Park, the football star and class president who went to Stanford, scored a Rhodes scholarship, and then attended Yale Law School. Time magazine called him the “savior of Newark” when he was just a city councilman (he made the cover as mayor), and he was practically beatified as the earnest underdog trying (and failing, that time, in 2002) to overthrow the strongman mayor, Sharpe James, in an Oscar-nominated documentary called Street Fight. (The movie came out in 2005, and Booker was elected overwhelmingly in 2006, after James dropped out of the race.) And then there’s all his other caped-crusader stuff, like rescuing people from burning buildings and dogs from the cold, and schmoozing his way to a $100 million donation for the Newark school system from Mark Zuckerberg.

“Cory Booker, Cory Booker, the Gecko’s looking for you!” squawks a nearby loudspeaker. “Come by the booth and get a high five from the Gecko!” The man in the space-lizard costume is in fact playing the role of that Cockney-accented insurance mascot, and—why not?—Booker seems to be delighted to meet him too.

When we turn off the boardwalk in Long Branch to be SUV’d to Asbury Park, Bradley ribs his friend: “Oh, Cory; oh my God, it’s Cory Booker!” he squeals, flinging his arms around the mayor.

When I ask the normally aloof Bradley why Booker deserves the job, Bradley looks like an old warrior happy to be back on message, and enumerates: “To describe Cory in three words: idealism. Empathy. And intelligence.”

“I’m okay with that,” Booker says, with his default setting of deferential buoyancy (you can see why grown-ups have always liked him). “I was waiting for the good-looks part.”

“When you lose 50 pounds, then I’ll give you that.”

Booker laughs. Come to think of it, he is surprisingly chubby for a vegetarian who never drinks alcohol.

“I started at a very young age as being Mister, sort of, Responsible,” Booker tells me later, nominally in response to a question about his teetotaling. “When my friends started drinking in the early high-school years, I was always the guy that held people’s hair back when they puked, took care of people, being the designated driver,” he says. “And those things become part of your identity. And then 21 hit and I realized, ‘You know what? I don’t need alcohol.’ It’s a variable. And I’ve got an equation in my life where I don’t really want another variable in my equation.”

Booker has spent seven years now as the super-tweeting superhero of Newark—living for years in a housing project that has since been torn down, camping out in a drug marketplace, inviting Sandy refugees over to his house to watch his sci-fi DVDs, and, recently, living for a week on a food-stamp budget of $4 a day. Many Jersey Democrats wanted Booker to run for governor against Chris Christie, that other ascendant Jersey politico, even though they thought he probably couldn’t win. (Booker insists he could have beaten Christie, but thought senator was a better fit.)

And next week, in an all-but-certified primary that precedes what promises to be a similarly speed-bump-less special election in October to fill the seat vacated after Senator Frank Lautenberg died earlier this year, Booker will be effectively anointed one of the most famous junior senators in the country, a pop star of purposeful post-partisan humanism.

Booker’s opponents in the primary—journeymen congressmen Frank Pallone and Rush Holt—are well qualified, with solid records and accomplishments for the state. But nobody has ever heard much from them outside of their districts, and since the special election is happening so quickly, the thinking is that they don’t stand a chance against the mayor’s name in lights. Newark has only a quarter-million residents, but Booker’s got over 1.4 million Twitter followers; part ownership in a social-media platform called #waywire (where Jeff Zucker’s teenage son is on the board); regular TV-news-chat-show appearances and a role on a Sundance-channel reality show called Brick City; and high-altitude friendships with Gayle King, Rachel Maddow, and Zuckerberg, as well as hedge-fund bigs like Bill Ackman, Leon G. Cooperman, and Boykin Curry (whose brother, Marshall, made Street Fight). This is not the profile of a regional politician on the rise but an already-national figure seeking to take his show to a more prominent venue. Buzzworthy Booker has pretty much his own dedicated beat writer on BuzzFeed and both writes for and is covered extensively by his friend Arianna Huffington’s little news blog. If last year the Star-Ledger figured out that he was away from Newark almost a quarter of the time—his critics say the day-to-day mechanics of municipal government increasingly bore him—that doesn’t seem to threaten his way to the Senate, where he’ll represent one of the country’s wealthiest states from one of its poorest corners.

The story of Booker’s career has always been a story of ascent, about moving from one place to another with adaptive ease. Booker’s a private-equity-friendly, venture-capital-conversant Bloombergian pragmatist who can talk “solutionism,” and can do it in the urgent poetics of the black church, in which he grew up. (He calls poverty our “American apartheid.”) He knows more about Judaism than most suburban Jews he meets—which isn’t a bad fund-raising shtick—but also spent time with Deepak Chopra in an ashram in India, and he tweets out so many uplifting quotes that Huffington joked to me that if you follow his feed for a day, you can build a commencement speech. A management consultant in community-organizer clothing, and an underclass fix-it man with a locally tested policy pitch he can retail nationally, Booker’s running to be the social-media senator from the Twitterocratic nation of tomorrow.

“My constituency is technically only 280,000 people,” he said earlier this year at SXSW in Austin (at an event named, auspiciously: “Cory Booker: New Media Politician”), “but it’s also the United States. It’s time to wake people up again, and we can do that.”

Newark is only about ten miles from Manhattan, but it seems further, and if you make the mistake of taking the pokey path train, the trip can take as long as an hour.

The city is the largest in New Jersey, but it’s a pretty small place, too—it’s an easy walk from Newark Penn Station and its surrounding unfriendly fortress of modern office buildings to the Robert Treat Center, where Booker has his campaign offices in a well-worn, circa-1916 building. And it’s not much of a hike from there to the impressive old City Hall. Walk just a few minutes farther, up past All Brothers Liquors #1 and a grand former synagogue turned Church of God in Christ, and you reach Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. On one side of the street is an Islamic center broadcasting a loudspeaker message about absentee fathers and hellfire; look east, and there’s downtown Manhattan in the distance. This is the street of the Brick Towers projects, where the legend of Booker in Newark found its footing. More than a decade later, with Booker poised to leave for Washington, the towers have been torn down, with the as-yet-unfulfilled promise of a more comfortable, smaller-scale development to replace them, and the block renamed for Virginia Jones, the local activist who encouraged Booker, then a tenants-rights lawyer, to run for office.

As usual, the mayor is tightly scheduled, and it’s decided we’ll meet downstairs from his office, in the lobby of the Best Western next door. There’s a plaque commemorating all of the presidents the hotel has hosted: Wilson, FDR, Truman, JFK. But none, it seems, since the 1967 riots (some in the city prefer the word rebellion). Visible behind Booker, through the plate-glass window, is the derelict brick façade of the former S. Klein department store, which is being torn down for an expansion of the Prudential Insurance headquarters.

The mission Booker set for himself as mayor went beyond the usual duties—to reduce crime, tinker with social programs, and try to keep the economic-development machinery greased (his hands were tied with the schools, since the state had taken control of them in the mid-nineties). He wanted to change the very idea of Newark, from a place trapped as if under a dome by demography and despair, into a cause. “Newark used to be so much beloved by people who are no longer there,” says Clem Price, a history professor at Rutgers. “Cory was the way for them to reconnect.”

“When I first became mayor, it took me about five years until people started returning my calls,” Booker tells me. “It took a lot of things, from Twitter to media, to get to the point where I can call people.”

Those calls have helped make a city with 13 percent unemployment, and only 13 percent holding college degrees, hemmed in by structurally better-off towns in economically and socially Balkanized New Jersey, into a vast public-private experiment in urban reboot. Booker has long been backed by well-intentioned outsiders, from Oprah Winfrey to Goldman Sachs bankers, and all told, he has helped bring $400 million in philanthropic support to his city, the most spectacular being that $100 million in Facebook stock from Zuckerberg. The gift was announced on Oprah and given on the condition that Booker and allies raise a matching amount. But in order to score that haul, Booker first had to insinuate himself into the annual Allen & Co. tech-plutocrat retreat in Sun Valley. And before he could sidle up to Zuck at a buffet dinner there, it helped that he was already friends with Sheryl Sandberg.

“The era of big government is over, as Clinton said,” he tells me by way of introducing his brand of appealingly purple, network-y wonkery. “It’s really about smart investing. A government that invests in a smart way that produces returns for everybody, that empowers human potential and produces a return for everyone.” This language of M.B.A. spirituality comes naturally to Booker, and he understands that this is part of why the business elites trust him.

“I can take somebody who has an investor’s mind and show them a fatherhood program that for a small amount of investment has saved New Jersey taxpayers millions of dollars in terms of the recidivism from over 60 percent to under 10 percent. They get it instinctively. Forget Republican, Democrat. Forget ideology, left or right. This is strategic investment to empower the productivity of thousands of Americans to lower government expenditures over the long term.”

It makes sense that a man like Booker, who has done so well by the system, wants to engineer sensible, sensitive change within it. He gives off an oddly endearing, protect-me aura—helped by his professions of romantic haplessness. He’s hardly ever publicly impertinent or rash, with probably one major exception—when his sympathy for bankers led him to call the Obama campaign’s Bain-inspired attacks on private equity “nauseating.”

Marveling at this skill, one prominent Jersey Democrat recalled how, after seeing Booker give the commencement address at Cornell earlier this year, “these Republicans I know were so blown away. They texted me: Is this guy really a Democrat? He’s fabulous.” Last week, “Page Six” reported that Ivanka Trump, whose father is a birther, and Jersey development scion Jared Kushner, whose New York Observer backed Mitt Romney, hosted a fund-raiser for Booker, giving him his biggest haul to date: $375,000.

Andra Gillespie, today a political-science professor at Emory, saw Booker deliver the 2001 Fowler Harper Lecture at Yale Law School—a gig that often goes to a more seasoned alum, but (of course) Booker was asked back just two years out of law school. She was so impressed she decided to do her dissertation research on minority-voter turnout in Newark, teaming up with, and finally volunteering for, his campaign. She returned later to do more research, which turned into a book, The New Black Politician: Cory Booker, Newark and Post-Racial America. In it, she describes Booker as a member of a new generation of post-civil-rights activists whom she calls “Black Political Entrepreneurs.” Part of what characterizes them is their appeal to white voters, she wrote, and their willingness to experiment. Once he was in office, “Booker shifted the focus of his government proposals from process to customer service.”

Back in Newark, Booker and I are talking, as he does often and well, about his own family’s story, and the lessons that come from it. His father, who didn’t know his own father, is from North Carolina, and his eventual success—one of the first black executives at IBM—depended on the fact that his community got together to help send him to college. “How do you put in place that kind of structure that broke my dad out of poverty? It’s something that weighs on me all the time.” His mother was born in Detroit, in better circumstances, and later moved to Louisiana and then Los Angeles. His grandfather worked in the bomber factory—“Those were the stories of the boom years,” Booker says. Then, starting in the fifties with suburbanization, things went badly, quickly, for industrial cities. “Unfortunately, it’s a story that repeated itself in numerous cities: massive declines in tax bases, massive corruption, middle-class exodus …”

An exhausted-looking aide holds a tape recorder in the other chair to make sure his boss is quoted correctly. Another aide sweeps in with coffee without being asked—“It’s Aquaman telepathy,” Booker jokes.

Newark always meant something for Booker: According to his high-school friend Jim Donofrio, while everybody else was dreaming about playing for the Mets or the E Street Band, Booker—the class president; one of the captains of the football, basketball, and track teams; and even then a friend to all cliques—knew that he wanted to be Newark’s mayor “to turn the city around.” He had a dentist there, as well as non-blood relations he still considers “family,” Booker explains.

Two of those “relatives” showed up in Asbury Park during the July 4th boardwalk walk, grinning and delighted to watch their successful “God-cousin” scoop ice cream next to Bradley, giving off that same big-brother jollity they always remember in him. They don’t see the mayor often, they tell me, looking on adoringly. But sometimes they connect with him on Twitter.

Not everyone in Newark, or in the New Jersey political Establishment, has always appreciated Booker’s good intentions (this is a state in which regional party leaders are matter-of-factly referred to as “political bosses”). And there are lots of political vets who resent his refusal to play by their rules—he can go over their heads, right to the public. When I mention this to Bradley, he says sarcastically: “I’m shocked—shocked—that people who are in machine politics are upset that Cory doesn’t play that game.”

Reservations aside, for the most part the party Establishment is behind Booker in this race—it’s good to back a winner. On the question of his tenure as mayor, they are more divided. Any account of those years must start with the fact that the city has gotten a bit safer since he took office, and that its population is growing for the first time in decades. But many Jersey politicos think he’s spent more time grooming himself for the publicity Elysium where Oprah and Zuckerberg hover in white robes writing big checks rather than hanging out in the city’s rusty old governmental engine room, tinkering. They wonder if tweeting is the same thing as governing. That perhaps it wasn’t enough to be so ostentatiously the only honest man in a corrupt city, that this was a task that required more than multitasking. “Cory is a big-idea public figure,” notes Price. “At the same time, the nitty-gritty workmanship of [being] a city mayor doesn’t seem to appeal to him.” So maybe the Senate is better suited to his many talents.

As one critic who once had the job he’s hoping to land, Bob Torricelli, puts it to me ominously: “The scenario of this almost immediate election ensures that the Cory Booker story in Newark is never going to really be told.” When Josh Lautenberg, the late senator’s son, endorsed Booker’s opponent Pallone, he put it this way: “My father was known as a workhorse, not a show horse … But he [saw] Cory as a show horse, not a workhorse, something that, in his guts, bothered him.”

Booker is aware of the carpetbagger critique, and is careful to present his story as an uncynical one, his evident ambition almost edited out. “There’s a purity of being in the nonprofit world,” he says, a little enviously. “If you’re in the nonprofit world, and you help somebody cross the street, you’re a good guy; if you’re a politician, you’re trying to get their vote.” As he always tells it, Virginia Jones had to persuade Booker to run for office—“She chipped away at my resistance”—but according to Gillespie’s book, Booker went to Jones asking for her support. Perhaps that discrepancy is just a matter of divergent memories, but it’s always been important for Booker to present himself as something other than the on-the-go, inevitably ascendant Cory. The truth as he sees it is that it’s all just him, a single man, childless, hard at work for his constituents at all hours.

When I mention the “show horse” quote to Booker at the Best Western, he scoffs: “That slant of argument worked really well for John McCain.”

See Also:

What Is Chris Christie Doing Right?