Four days before Christmas, Police Commissioner Ray Kelly had especially good reason to celebrate. Beyond the windows of his office at One Police Plaza, nightfall was nudging all of New York one sunset closer to a milestone that must have been particularly gratifying to the city’s 66-year-old top cop. For the first time since the NYPD began keeping reliable records in 1963, the number of homicides recorded in all five boroughs was likely to fall below 500 for the entire year. Murder was down almost 80 percent in seventeen years. A reasonable person might even conclude that it was a nasty old habit just one New Year’s resolution away from extinction. Not Kelly. Asked if he could envision any combination of measures that could push the murder rate to zero, the commissioner opted for a joke. “Mass evacuation,” he said.

That same joke might have been made in 1990, of course, when homicides peaked at 2,245 and New York reigned as the murder capital of America. The difference today is that the city has succeeded in shrinking the eternal problem of human violence to a size that invites purposeful dreaming. In the New York City of 2008, the most interesting question is no longer can violent crime go lower but what would it take—if we were willing to consider everything short of a mass evacuation—to make homicide extinct?

There is ultimately no such thing as an irreducible level of violence in the city—violent crime can always go lower. It’s a matter of deciding what costs we’re willing to incur, how much Big Brother we’re willing to let into our lives, how much faith we put in science to curb the excesses of human behavior. Trying nothing new would be the easiest way forward. Surprisingly, that’s a strategy worth deeper consideration.

Solution 1.

Let the game ride.

It would help our thought experiment, of course, if everyone agreed up front how murder dropped as low as it has. Commissioner Kelly is among those who argue that the size of the police force made the biggest difference. In 1990, when David Dinkins was mayor, it was Kelly, then first deputy commissioner and soon to be promoted to the top job, who spearheaded a successful effort to increase the NYPD’s manpower by 25 percent. “There’s a direct correlation between boots on the ground and crime reduction,” he says. “That’s how we do our business—people.” The difficulty with proving that argument is that Kelly’s immediate successor as commissioner revolutionized police management, thus blurring the benefits of pure shoe leather.

The consensus among academics these days is that the NYPD benefited substantially in the nineties from broader trends that were bringing down crime rates across the country. Though the city’s crime-age population was initially growing and its economy was in recession, the crack boom of the eighties was settling into a less-volatile middle age by 1991. How much credit can the police reasonably claim for the crime declines? Franklin Zimring, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, has constructed a strong argument that puts the number at 25 to 50 percent.

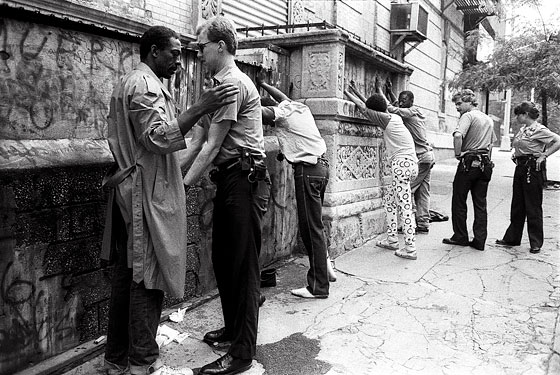

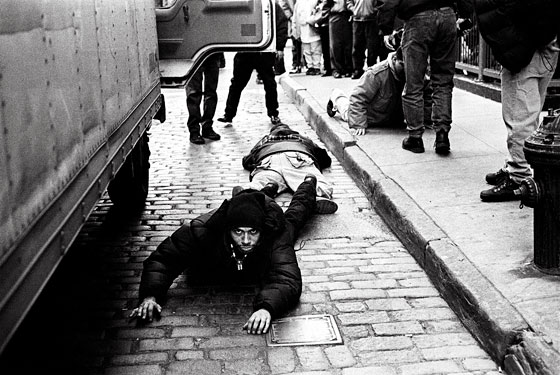

New York’s declines would take their steepest drops after Rudy Giuliani was elected and chose William Bratton to be Kelly’s successor. Much of Bratton’s initial success came from targeting street guns and giving free rein to his colorful deputy, Jack Maple, who demanded that crime be tracked daily and that precinct commanders arrive at regular meetings downtown prepared to explain how problems on their turf were being addressed. Maple’s system, which became known as CompStat, made the perpetual pursuit of a safer city the central business of the NYPD for the first time.

Looking back at the city’s early victories against homicides now, one could argue that members of Bratton’s regime plucked the lowest-hanging fruit. They resolved to make carrying an illegal gun a serious arrest risk, and sure enough, arrest records indicate that New Yorkers began leaving their guns at home. Shootings declined dramatically, and so did shooting murders. What’s more, Bratton’s crew had first crack at the city’s busiest drug-world enforcers, its biggest illegal-gun dealers, and its most incompetent push-in robbers. By 1997, the annual murder count had fallen to 770. By the time Kelly reclaimed his old post in January 2002, following the reigns of Howard Safir and Bernie Kerik, national crime numbers were flattening out or rising. Yet Kelly became the first commissioner to break the 600 threshold. To Zimring, the more modest declines of the past seven years, unaided by national trends, might be entirely due to the NYPD’s efforts.

Kelly hasn’t abandoned CompStat. He’s embraced new technology that speeds the flow of information to cops in the field, and he’s borrowed CompStat’s mapping logic to create his own signature anti-crime program. Rather than spreading police academy graduates throughout all five boroughs, Kelly has been sending most of his rookies to about twenty small hot spots across the city where crime remains stubbornly high. He recently announced plans to double the manpower, a show of force he and Mayor Michael Bloomberg hope will further discourage illegal activity.

Meanwhile, the constant, organizationwide pressure to beat the crime numbers of previous years produces a certain momentum. The caseload is diminishing. That means the murder rate might keep falling if law enforcement keeps doing what it has been doing.

Solution 2.

Decriminalize drugs.

One of the most encouraging developments to emerge in recent years is that it has become increasingly unlikely that the victim of a New York City slaying will never before have set eyes on his or her killer. Police estimate that fewer than 100 of last year’s 494 homicides involved perpetrators who were strangers to their victims. That represents a drop of 100 stranger-on-stranger homicides since 2004, and more than 600 since 1993.

The 400-plus murders that involve killers known to their victims can be broken into two broad categories. While a sizable share could be labeled crimes of passion, the first area to look for significant gains may be in homicides that can be attributed to particular economic and social incentives.

The most obvious source of such incentives is the illegal drug trade. Economist Steven Levitt and journalist Stephen Dubner, the authors of the 2005 best seller Freakonomics, have a bracing prescription for effecting a radical pacification of New York: Legalize drugs. “If drugs were legal, they wouldn’t be sold on street corners by gangs; they’d be grocery-store commodities,” they wrote in a recent e-mail. “Drug-related homicides—which is to say, the bulk of all homicides—would probably vanish.”

Levitt and Dubner may be overestimating how many murders the drug trade contributes to New York’s tally. The NYPD’s chief spokesman, Paul Browne, concedes that the drug trade may play a role in more than half of the city’s homicides, but only about a quarter are formally categorized that way. The rest likely have to come from murders that the police attribute to “disputes” (27 percent in 2006), “revenge” (10 percent), robbery/burglary (10 percent), and gangs (6 percent).

But Levitt and Dubner are undoubtedly right that the great majority of drug-related homicides are perpetrated by sellers and distributors, not by end-of-the-line customers. The violence associated with the trade arises, they say, because business disputes between sellers can never be settled through, say, an advertising war or a civil lawsuit. “In the 1920s, Al Capone and his rivals left a trail of dead bodies as they fought over the profits from bootlegged liquor,” the pair wrote. “When Prohibition ended, it was folks like Anheuser-Busch who took over the business.”

The Mafia allusion, however, points to an inescapable limit on how many murders drug legalization would eliminate. Enterprising criminals will always find another market when one is taken away from them. If they fail to come up with a new drug that can compete with FDA-approved heroin, they can start extorting construction-site managers or robbing check-cashing outlets. The bodies of their victims or rivals would still pile up. Incentives, in other words, are slippery things. Shutting down the illegal-drug market would eliminate all commerce-based killings only if it also triggered, or coincided with, a widespread cultural shift.

There are less theatrical ways to change the incentives equation, though, than legalizing narcotics. Every after-school chess club or career program has a chance to tip the balance for a handful of kids. When crime is in retreat, small-bore efforts become that much more pivotal.

Solution 3.

Play marriage cop.

A success story that emerged last year in the NYPD’s domestic-violence division suggests that even some of the most stubborn categories of homicide might be vulnerable to the soft weapon of increased attention.

Homicides that occur within families, of course, often exemplify the type of murderous behavior that many observers consider immune to intervention—a man “snaps” and kills his wife, a mother “snaps” and kills her children. The conventional wisdom is that there’s only so much law enforcement can do to foresee these situations.

Deputy Chief Kathy Ryan, the commanding officer of the NYPD’s domestic-violence unit, had put three years of effort into reducing family-related homicides without seeing dramatic change in the numbers. But while domestic-violence murders hugged close to the 70 mark each year, she remained committed to increasing police visits to homes with histories of domestic violence. In 2001, trained officers made 33,400 such visits. Under Ryan, visits rose to more than 76,000 last year, and big results finally followed: Only 45 domestic-violence homicides were recorded in 2007.

Ryan says that the home visits accomplish many things. They give abusers a sense of being watched. They give the weaker party in a home a sense of having allies. They sometimes even catch an offender lording over a household that he’s barred from by a court order. Not surprisingly, the big decline in domestic-violence murders occurred in households that police already knew were problem homes. Such homicides are down about 64 percent since 2002, for a total of just 10, compared with a decline of about 27 percent in the much larger group of murders that come without warning.

The only tactic Ryan can identify as an explanation for the latter decline is as soft a government intervention as you could find. Along with Mayor Bloomberg’s office, the city’s Department of Health, and the borough D.A.’s offices, Ryan’s division has participated in a huge push in recent years to spread public awareness about domestic violence. Through lectures and handouts printed in various languages, victims and witnesses to domestic violence are learning that a network of agencies is ready to intervene before a troubled relationship gets worse. Such efforts, limp as they may sound, could be law enforcement’s future.

Still, in another corner of Ryan’s world, police are about to begin an experiment that feels more stern and futuristic. Sometime this winter, the first of a few dozen domestic-violence offenders in Queens and Brooklyn will strap on a small ankle bracelet that he’s agreed to wear in lieu of serving jail time. A Global Positioning System on the bracelet will indicate where the offender is at all times. If he wanders too close to a home, school, or workplace covered by a protection order, a radio car will automatically be dispatched to the site and a call will be placed to the individual in danger. The hope is not to catch domestic abuse in action, but to preempt it.

Solution 4.

Get inside the would-be killer’s head.

Surveillance is expanding quietly into our lives, perhaps too stealthily so far to affect behavior. The whole city is filling gradually with cameras that feed street scenes directly to a command room just downstairs from Ray Kelly’s office. Though only lower Manhattan is likely to receive virtual blanket coverage by government cameras in the very near future, the NYPD’s reach is growing. Already, there are patrol cars in every borough equipped with electronic license-plate readers that automatically feed every passing plate into a searchable computer database.

How far surveillance can go isn’t hard to imagine for anyone who’s ever read a Philip K. Dick novel. Guido Frank, a child psychiatrist at the University of Colorado, Denver, has already been using brain-imaging technology to peer inside the brains of a small group of aggressive teenagers to isolate the causes of violent behavior.

Back when murder was peaking in New York, some brain scientists believed that biology soon would be able to identify “a violence gene.” Though that quest proved quixotic, subsequent findings have largely confirmed that particular physical and physiological characteristics of the brain, some genetic, are common to individuals predisposed to violence. The intriguing twist is that “criminal” thought patterns only emerge in such brains if they’ve been ill fed both by damaging individual experiences and by the surrounding culture. Neurology is now all but saying, in other words, that both childhood abuse and Hollywood shoot-’em-ups really do matter when it comes to a society’s level of violence.

Frank has focused on five teenagers in whom the damage of life experiences has already been done, and the consistency of his findings has been startling. Three separate segments of the brain functioned abnormally when these participants were asked to perform particular tasks. When the teenagers were shown images of angry faces, the amygdala, which registers threats, became overactivated, while the ventral striatum, the brain’s reward center, lit up much as it would after sex or a bite of chocolate. “These kids may get some pleasure out of aggressive responses,” Frank says. In a separate test, the prefrontal cortex, the segment of the brain that moderates impulses, responded feebly to control emotional responses.

A troubling question is what society should do once such an individual is identified. Frank wants to use further brain-imaging studies to test various medications and counseling strategies, either of which might eventually lead to healthier thought patterns. But a city confident that it had identified its most dangerous citizens could conceivably adopt a less therapeutic posture. The possibilities are frightening to consider.

Solution 5.

Gentrify the entire city and make everyone a homeowner.

The falling murder rates have produced at least one distressing subtrend. Over the past three years, as homicides have dropped 13 percent, it has become increasingly likely that a New York City murder victim will be a person of color and that the murder will occur outside Manhattan. In 2007, according to police statistics, 90 percent of the city’s homicide victims were black or Hispanic, up from 86 percent in 2004.

When ex-convict Glenn “China” Martin returns to his old block in Prospect Heights, he wonders if New York solved its crime problem through the relocation of high-risk populations. The street outside his mother’s apartment, once a dangerous heroin supermarket, is now a quiet enclave of mostly white professionals and their fancy dogs. One of Martin’s greatest regrets is that he didn’t buy in when the first building on the block went condo. In 1993, $130,000 for a Prospect Heights apartment seemed insane. “Today,” he says, “it’s more like, ‘I’ll take two.’ ”

Martin, a 37-year-old native of Grenada, served six years behind bars beginning in 1995 after a lucrative career in jewelry-store robberies was cut short. With the honest money he now brings in advocating for just-released prisoners at Manhattan’s Fortune Society, he’s already bought two apartments deeper into Brooklyn, hoping to catch the next wave of gentrification. Martin is a big believer in the crime-suppressing power of private investment. When you have lots of property owners living in a community, he says, residents are less likely to let a drug dealer set up shop on the corner. “People are then willing to stand up and say, ‘Not in my neighborhood.’ ”

But while Martin is pleased that his mother can now return from her Manhattan clerical job without fearing the short walk from the Brooklyn Museum subway stop to her rent-stabilized apartment, he worries about the other poor families on Lincoln Place who’ve been priced out. The men Martin served prison terms alongside, he says, aren’t building new lives in up-and-coming Prospect Heights. They’re taking apartments in Brownsville and East New York, or moving to smaller cities upstate, often carrying their troubles with them. “I wouldn’t live in those places,” he says. “They’re too dangerous.”

That comment would mean less if East New York and Brownsville weren’t among the only neighborhoods in the city that recorded rises in homicides last year. In northern Brooklyn’s ten precincts, shootings were up 11 percent in 2007. It’s too simple to say that the city has succeeded merely in displacing crime, driving it outside the boroughs’ boundaries or corralling it into a few unlucky New York neighborhoods. After all, East New York and Brownsville are much safer than they were in 1990, and Commissioner Kelly is sending more cops to those neighborhoods to address the violence.

Is something more radical needed? Would a government-sponsored mass home-ownership program eliminate crime in New York? Of course not. But a city that still witnesses the senseless loss of 500 of its citizens each year can’t afford to become complacent, nor can it ignore the opportunities that years of growing public safety provide. Now is a very good moment to consider the kind of city New York should be in the future, and the kind we don’t want it to be.

The persistence of crime within a handful of neighborhoods feeds a worry that adds to the urgency. Another citywide epidemic is never out of the question. What might it take to unleash one? It’s hard to imagine that the police would suddenly forget all they’ve learned in the last two decades. Still, it has been a long time since law enforcement has been tested by a sustained economic downturn or the arrival of a new market-making street product like crack or the semiautomatic handgun. Looking around the city today, Glenn Martin sees plenty of reasons that even economically challenged young men would choose legitimate paths to stature and wealth. “Crime,” he says, “is just not as cool as it used to be in a city that’s taking off economically.” No one really knows, though, if the same calculus will hold true tomorrow.

The Body Count

1963:548 murders

1964:636

1965: 634

First blackout is generally peaceful.

1966: 654

1967:746

1968:986

Columbia riots.

1969:1,043

1970:1,117

1971:1,466

Attica uprising.

1972:1,691

1973:1,680

Rockefeller drug laws enacted.

1974:1,554

1975:1,645

1976:1,622

1977:1,557

Koch elected on pro-death-penalty platform. Blackout II, this time with riots. Son of Sam.

1978:1,504

1979:1,733

1980:1,814

1981:1,826

1982:1,668

1983:1,622

Michael Stewart killing.

1984:1,450

Crack arrives in NYC. Eleanor Bumpurs killing.

1985:1,384

1986:1,582

1987:1,672

1988:1,896

Tompkins Square riots.

1989:1,905

1990:2,245

Murder rate peaks. NYPD starts major hiring spree. Bratton takes over Transit Police.

1991:2,154

Subway crime drops.

1992:1,995

Dinkins appoints Ray Kelly police commissioner.

1993:1,946

1994:1,561

Rudy takes command! And Bratton goes atop NYPD.

1995:1,177

1996:983

Bratton’s out; Safir is in.

1997:770

1998:633

1999:671

Amadou Diallo killed.

2000:673

Safir out, Kerik in.

2001:649

2002:587

Bloomberg takes office, brings back Ray Kelly. Street Crimes Unit disbanded.

2003:597

2004:570

2005:539

2006:596

Uptick in murder rates. Have we hit bottom?

2007:494