I don’t remember the beating. Whoever did it stole $28 from me, and about ten minutes of my consciousness. From the inside, however, those ten minutes felt like ten hours: It was warm, soft—gooey even. In reality, I took a violent blow to the side of my head. But I remember it as peaceful. I was floating in an infinite amniotic sea of blackness, and every time I peered in a new direction, a bloodred light would bloom out of the void and then slowly start to pulse. It was a hellish color scheme, but it felt like heaven.

I knew I wasn’t dead because I woke up to some guy in my face telling me over and over that I was “going to be okay,” except he looked really worried. What was he talking about? There was a crowd of people looking down at me. And behind them, the ceiling. It was disgusting: stalactites of flaking paint, encrusted with dried slime. I recognized that ceiling and realized where I was: on the floor of my local subway station, Morgan Avenue—six stops beyond Manhattan on the L line, in Bushwick, a half-block from my home.

Bushwick is big (it’s like saying “the Village”). It’s also notoriously bad. Bushwick suffered the worst of the rioting that struck New York in the summer of 1977. The area is home to a mostly poor Hispanic and African-American population, though there are pockets of gentrification. My corner of the neighborhood, a loft district that the city is trying to re-brand as the “East Williamsburg Industrial Park,” mostly warehouses kids just out of art school. It’s a bleak, rubble-strewn landscape pocked by cement factories and hemmed in by towering projects. When I moved to the neighborhood, some of my friends were spooked by the blight, but I only saw the beauty. This is what Soho in the early seventies or Tribeca in the early eighties must have felt like, I thought. When I came to New York almost twenty years ago, those places had been overrun. But when I got to Bushwick, I knew I had finally found the New York I was searching for—a scrappy loft neighborhood full of young bohemians camping in their studios. This was the pre-gentrified New York I wanted to be a part of.

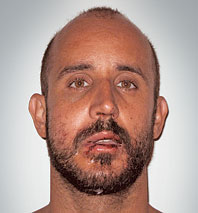

At the other end of the ambulance ride, in the trauma unit at Elmhurst hospital in Queens, the physician on duty took one look at me and said, “Well, they almost certainly broke your right maxillary”—later I learned that this was doctorspeak for my upper jaw—“and I want to get a cat scan of your head, too, to check for bleeding into your brain.” The doctors told me that even a hairline fracture in the bones of the front of the skull is a serious matter: The many tiny muscles that control the movement of the eyes can easily get caught in a crack, leaving you disfigured. Luckily, however, I needed nothing but stitches for my split lip and the gash on my chin. Weirdly, I felt no pain at all even as they sewed me up—and because of a mix-up, there was no local anesthetic. Just happy to be alive, I guess.

After the doctors came detectives from the NYPD, and they could not have been nicer or more professional. They lost a bit of interest, however, after I told them that I couldn’t identify my attackers. The best I could do was describe the arm that hooked over my shoulder to pull me into a choke hold: It was big, muscular, and black. The second guy I barely glimpsed; a witness apparently said he was Hispanic, but I didn’t register his skin color—just that his clothes were clean and crisp. The last thing I remember is putting my hands up, MetroCard in my right, wallet in my left.

Everybody has a different theory about what hit me. The doctor said that it was no fist. The cops thought a pipe or maybe a two-by-four. A public defender I talked to said that her clients usually use the butt of a gun. I don’t know. I’m just glad that there isn’t any permanent damage, or not much, anyway. Three months later, I still have some numbness and a semi-black eye—“semi” because the blackness only comes out when I’m tired.

The real drama of the attack was its aftermath. Within 24 hours of my release from the hospital, I made it back to San Francisco, where I grew up; within 48 hours, I decided to quit my job and move back there; and by the end of the week, it was done: I had given notice to my landlord, quit my job, and asked my girlfriend to move in with me. It all made perfect sense to me, a row of falling dominoes. The only thing I couldn’t understand was why everyone kept acting like I had post-traumatic stress disorder. “Only a flesh wound!” I joked. Now I understand, because in retrospect, I realize that maybe I do have a touch of PTSD. I’m not quite the same person I was. Blight, graffiti, empty buildings—the signifiers of every artsy New York neighborhood for the last 40 years—have lost the romantic appeal they once held. I carry a knife now, a small utility blade that I picked up at the hardware store. And when friends of mine get nostalgic for the bad old days, when lofts were cheap and New York was edgy, I tell them that it’s all still there, if you know where to look.