This article was featured in Reread: Real Estate Mania, a newsletter miniseries resurfacing classic stories of eye-popping prices, the next hot neighborhood, and some truly nightmarish living situations from the New York archives. To read them all, sign up here.

Additional reporting by Michael Hudson of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Part I: The Buyer

The buyer, an Italian, was in town for a week, with a million or so dollars to spend. We met one Sunday morning at 20 Pine, a Financial District condo building. She wore a red scarf, jangly jewelry, and a pair of lime-green sunglasses perched atop her curly hair, and she told me she would prefer to remain anonymous. Working through a shell company, she was looking to anchor some of her wealth in an advantageous port: New York City.

The building’s lobby, designed in leathery tones by Armani, swirled with polylingual property talk. As the Italian and I waited for her broker, an Asian man sitting on a couch next to us asked, “You see the apartment?” But he didn’t wait for an answer, leaping up to join a handful of women speaking a foreign language heading toward the elevators.

After a few minutes, a fashionably stubbled young man swung through 20 Pine’s revolving door: Santo Rosabianca, a broker with Wire International Realty. The firm, run by Rosabianca’s brother Luigi, an attorney, specializes in catering to overseas investors. A first-generation American, Santo greeted the buyer with kisses and briefed her in Italian. She was searching for a property that would generate substantial rental income. “Wall Street is not my favorite place,” she told me. “But he says it is very good for rent.”

Like several other buildings she was being shown, 20 Pine was developed at the height of the real-estate bubble. After the crash of 2008, it became an emblematic disaster, with the developers selling units in bulk at desperation prices, until opportunistic foreigners swooped in with cash offers. The salvage deals are long gone, but 20 Pine retains its international appeal. The one-bedroom the Italian was looking at, on the 27th floor, had a view of the Woolworth Building, sleek finishes, a bachelor-size kitchen, and access to an exclusive terrace reserved for upper-floor residents. It was first purchased by an investment banker in early 2008 for $1.3 million, was resold in 2011 for $850,000, and was now back on the market for close to its prerecession price. Rosabianca told the Italian it would rent for more than $4,000 a month, enough to assure a healthy cash flow while its value appreciated. “There’s really no safer way to get that kind of return,” he said, “than in New York City real estate.”

This is not exactly true—there’s plenty of risk in real estate, as the original crop of purchasers at 20 Pine discovered—but that hardly dampens the enthusiasm of foreign buyers, who have become an overpowering force in New York’s real-estate market. According to data compiled by the firm PropertyShark, since 2008, roughly 30 percent of condo sales in large-scale Manhattan developments have been to purchasers who either listed an overseas address or bought through an entity like a limited-liability corporation, a tactic rarely employed by local homebuyers but favored by foreign investors. Similarly, the firm Corcoran Sunshine, which markets luxury buildings, estimates that 35 percent of its sales since 2013 have been to international buyers, half from Asia, with the remainder roughly evenly split among Latin America, Europe, and the rest of the world. “The global elite,” says developer Michael Stern, “is basically looking for a safe-deposit box.”

The influx of global wealth is most visible on the ultrahigh end, as Stern and other builders are erecting spiraling condo towers and sales records are regularly shattered by foreign billionaires, like the Russian fertilizer oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev, purchaser of the most expensive condo in Manhattan’s history ($88 million), and Egyptian construction magnate Nassef Sawiris, who recently set the record for a co-op ($70 million). But much of the foreign money is coming in at lower price points, closer to the median for a Manhattan condo ($1.3 million and rising). In fact, if you’ve recently been outdone by an outrageous all-cash bid for an apartment, there’s a decent chance that, behind a generic corporate name, there’s a foreign buyer and an offshore bank account.

“A decade ago, it was just a small number of elite investors,” says Andrea Fiocchi, a lawyer at Reinhardt LLP, which caters to an international clientele. But now the market is broad and diversified: Fiocchi’s firm handled not only two of the ten most expensive residential sales in the city last year, but also a large volume of transactions at more mainstream prices. Buildings around Times Square and the Financial District are being marketed heavily overseas. One development project on John Street is “crowdfunding” $50,000 financing shares via the Prodigy Network, a marketing firm with offices in New York and Bogota. The Related Companies is using a federal program that promises green cards to foreign investors to raise cheap capital for its Hudson Yards project. (A website features a rendering and the slogan “Your Gateway to the U.S.A.”) Shortly before departing on a road show to Monte Carlo and other redoubts of European wealth a couple of months ago, one broker told me about his most adventurous strategy: buying, emptying, and renovating brownstones in Crown Heights. An Australian investment fund has done something similar in Bushwick.

The development, still under construction, has closed sales on 25 units to date. Of those, more than half were purchased by corporate entities.

62nd floor: Escape From New York LLC, $31.7 million

61st floor: L & HP Family LLC, $30.4 million

60th floor: Rainbow Choice International Limited, $30.6 million (Hong Kong)

59th floor: Efstalmar LLC, $30 million (Greece)

58th floor: Sso Enterprises LLC, $30.6 million

51st floor: Mjjms LLC, $20.4 million; Parksville Investments Corp, $7.6 million

50th floor: Andrey Dubinskiy, $7.5 million; Yu-Ting and Yu-Wen Huang, $19.1 million

49th floor: Shi-Tang Yeh, $17.8 million; Leland A. Swanson, $7.6 million

48th floor: Andrea and Richard Kringstein, $17.8 million; Professional Leasing and Consulting LLC, $8.1 million

47th floor: West 57-47B Realty Corp, $8.8 million

45th floor: Eli Lomita and Alice Sim, $6.9 million

44th floor: 44B LLC, $7 million

43rd floor: Metty Properties LLC, $7.3 million

42nd floor: Diane and Angelo A. Montagna, $6.6 million

41st floor: Core Apparel LLC, $6.8 million

40th floor: LSF 57 US Corp, $9.1 million; Condo 40C 157 West, LLC, $6.7 million: Shirley and Lillian Ea, $4 million (Canada)

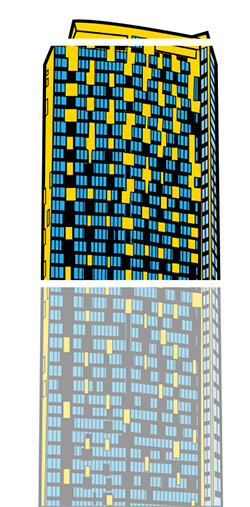

39th floor: Tao Liu, $3.5 million (China); Terry B. Johnson, $9 million; NYC Condo LLC, $7.5 millionPhoto: Illustration by Remie Geoffroi

And so New Yorkers with garden-variety affluence—the kind of buyers who require mortgages—are facing disheartening price wars as they compete for scarce inventory with investors who may seldom even turn on a light switch. The Census Bureau estimates that 30 percent of all apartments in the quadrant from 49th to 70th Streets between Fifth and Park are vacant at least ten months a year.

To cater to the tastes of their transient residents, developers are designing their projects with features like hotel-style services. And the new economy has spawned new service businesses, like XL Real Property Management, which takes care of all the niggling details—repairs, insurance, condo fees—for absentee buyers. “I feel like foreign investors have gotten a bad rap,” says Dylan Pichulik, XL’s boyish chief executive, who recently took me to see a $15,000-a-month rental at the Gretsch, a condo building in Williamsburg, which he oversees for a Russian owner. “Because, you know, They’re evil, they’re coming in to buy all our real estate. But it’s a major driver of the market right now.”

Even those with less reflexively hostile reactions to foreign buying competition might still wonder: Who are these people? An entire industry of brokers, lawyers, and tight-lipped advisers exists largely to keep anyone from discovering the answer. This is because, while New York real estate has significant drawbacks as an asset—it’s illiquid and costly to manage—it has a major selling point in its relative opacity. With a little creative corporate structuring, the ownership of a New York property can be made as untraceable as a numbered bank account. And that makes the city an island haven for those who want to stash cash in an increasingly monitored global financial system. “With everything that is going on in Switzerland in terms of transparency, people are being forced to pay taxes on their capital that they used to hold there,” says Rodrigo Nino, the president of the Prodigy Network. “Real estate is a great alternative.”

Those on the New York end of the transaction often don’t know—or don’t care to find out—the exact derivation of foreign money involved in these transactions. “Sometimes they come in with wires,” says Luigi Rosabianca. “Sometimes they come in with suitcases.” Most of the time, the motivation behind this movement of cash, and buyers’ desire for privacy, is legitimate, but sometimes it’s not. An inquiry by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a Washington-based nonprofit, has uncovered numerous cases in which New York real estate figured in foreign financial- and political-corruption scandals. “It’s something that is never discussed, but it’s the elephant in the room,” says Rosabianca. “Real estate is a wonderful way to cleanse money. Once you buy real estate, the derivation of that cash is forgotten.”

More typically, though, foreign buyers are searching for a favorable investment climate and the identity protection provided by an LLC. Rosabianca’s client, the Italian, lives in Nigeria, where her husband is in the oil business. But she said she was still a tax resident of her home country, giving me a knowing look. Italy taxes its citizens’ overseas assets—if it can find them. “To invest in Italy now is terrible,” she said. So the Italian spent most of her Sunday in taxis, bouncing from Gramercy to Tribeca to the High Line in search of the right place to store her wealth.

She ended up back downtown at 75 Wall Street, where she saw a unit she liked: a one-bedroom belonging to a Panamanian-owned company. She ended up making an offer on both that one and the condo at 20 Pine, but ultimately settled on yet another unit at 75 Wall for $1.3 million. The seller was also an LLC, its true owner unknown.

Part II: The Really Big Money

Every year, the British real-estate brokerage Knight Frank publishes a document called “The Wealth Report.” The latest edition produces the curiously precise estimate that there are 167,669 individuals in the world who are “ultrahigh net worth,” with assets exceeding $30 million. “Of course, the big question is: are the rich getting richer?” the report asks. It answers gleefully in the affirmative, forecasting that over the next decade, the ranks of the ultrarich will increase by 30 percent, with much of the growth coming in Asia and Africa.

This new global wealth is being lavished on the usual status items—planes, yachts, contemporary art—but Knight Frank is pleased to report that the rich favor real estate most of all. Real estate can serve as a convenient pied-à-terre, an investment hedge against a wobbly home currency, or an insurance policy—a literal refuge if things go bad. Other financial centers boast a similar mix of glamour and apparent security—Knight Frank’s list of the top-ten “global cities” includes London, Paris, Geneva, and Dubai—but New York is forecast to add more ultrahigh-net-worth individuals than any city outside Asia over the next decade.

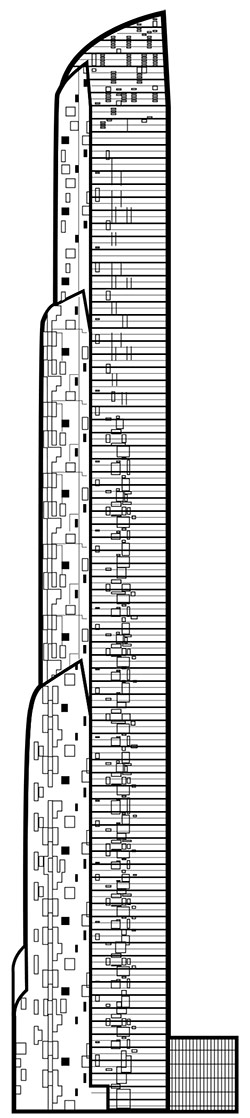

15 William Street hit the market in 2007, just before the crash. Foreign buyers took advantage, and it remains an attractive asset for global wealth. Of the 170 recorded sales between November 2008 and January of this year 9 listed a foreign address, and 87 were purchased through anonymous entities or listed only a lawyer’s contact information.Photo: Illustration by Remie Geoffroi

Daniela Sassoun, a Portuguese-speaking Corcoran broker who used to work in Swiss banking, frequently travels to São Paulo and Geneva to sell elite buyers on New York. “We give them the state of the market, and the lawyers explain how to purchase this under an LLC or a trust,” Sassoun says. “It’s wealth advisory: Here is an option for you to diversify your $100 million.”

Foreign direct investment in U.S. real estate amounted to $50 billion in 2012, according to the Congressional Research Service. The national firm RealtyTrac reports a recent rise in all-cash sales (a rough indicator of such investor activity) in the metropolitan areas of Florida and New York City, where well over half of all transactions in the first quarter were handled without financing. “Those are the coastal trophy markets for foreign buyers,” says Daren Blomquist of RealtyTrac. South American buyers are a particular force in Miami, where they are credited with reviving the city’s condo market after the ruinous real-estate crash.

No American city rivals New York, however, in the diversity of its wealthy population and the buying options it offers. As expensive as New York’s luxury real estate might seem, it’s a bargain compared to other global capitals; a million dollars will buy twice as much space here as it does in Monaco or Hong Kong. New York is perceived to be more stable than Miami, Shanghai, and Beijing. It is much cheaper than London, where tabloid-fanned outrage over property prices has created an uncomfortable political climate and various new or proposed taxes are aimed at foreign investors and offshore entities. In New York, by contrast, buyers of new construction often qualify for a tax abatement. At One57, currently the city’s most expensive new address, the tax break amounts to around 94 percent. A Times analysis estimated that its priciest penthouse, which is reportedly in contract for more than $90 million, would initially be billed less than $1,500 a month.

A luxury-skyscraper boom, fueled by international buying power, is casting a shadow over Central Park, where new and proposed towers are attempting to mimic the example of One57, which boasts of sales to every continent but Antarctica. At 432 Park Avenue, construction on a Rafael Viñoly–designed tower has ticked past 1,000 feet, and three more similarly scaled developments are on the way. Also, farther south, there’s a controversial tower by Jean Nouvel going up next to MoMA. Across the street is the Baccarat, affiliated with the crystal brand, which has been heavily marketed to foreign buyers. Up at 520 Park Avenue, Robert A.M. Stern is designing a building where prices will start at $27 million and run up to well over $100 million.

Much of this speculation is being driven by two factors: sparse supply, due to the absorption of the inventory left over from the last boom, and fast-rising prices. Manhattan saw a 30 percent price increase over the past year, on average, which market analyst Jonathan Miller attributes primarily to sales closing in ultraluxury buildings. The highest end of the market has seen stunning inflation. A decade ago, the Mexican financier David Martinez shattered a record when he bought a penthouse at the Time Warner Center for $42.5 million, or around $3,500 a square foot. “It was a huge number,” says Richard Wallgren, who was the sales director at the building. Wallgren is currently leading sales at 432 Park Avenue, which is being developed by Harry Macklowe and the CIM Group. Its most expensive penthouse has an asking price of $95 million—which works out to $11,000 a square foot.

432 Park Avenue and its competitors have historical antecedents, most notably Olympic Tower, built in the 1970s with financing by Aristotle Onassis. But the market really began to emerge a decade ago with 15 Central Park West, where Wallgren also handled sales. The development was initially marketed to local finance types, like Daniel Loeb and Sandy Weill, but it quickly attracted buyers from Israel, China, India, and elsewhere.

Many of these buyers took meticulous steps to conceal their identities. Some employed misdirection. The owner of a $37 million unit, Novgorod LLC, was widely believed to be a Russian oligarch until it was revealed to represent the chief executive of the British bank Barclays. (He later resigned in a financial scandal, but the LLC still owns the apartment.) Weill’s penthouse apartment was resold for $88 million in 2011 to an LLC owned by a trust in the name of Dmitry Rybolovlev’s daughter. During divorce proceedings, his wife filed a lawsuit claiming that the trust was a “sham entity” created to conceal the oligarch’s wealth.

Other investors in 15 Central Park West relied on the strict secrecy laws in offshore jurisdictions. Two units, for instance, were sold to Jolly Star Holding Limited, an entity registered in the British Virgin Islands, which guards the identity of shareholders. But confidential records obtained by the ICIJ as a part of a massive leak identify Jolly Star’s owners as Sun Min and Peter Mok Fung, a Chinese couple in the shipping business. A Hong Kong tribunal recently convicted Sun Min of trading on inside information related to Coca-Cola’s failed acquisition of a Chinese juice company in 2008, the same year she and her husband made their $15 million purchase.

Usually, however, there is no leak, and the identity of these owners remains unknown. “I believe in being unbelievably discreet,” says Bruce Cohen, a New York attorney who has handled transactions at many of the city’s most expensive buildings. Recently, his firm closed on two units at One57, one to a company called Metty Properties LLC and the other to an entity called Escape From New York LLC. Cohen declined to reveal any further details about either purchaser. Escape From New York LLC’s three-bedroom condo, purchased for $32 million, was immediately placed on the resale market. Asking price: $41 million.

Part III: The Soft Sell

The first rule of selling property to the ultrarich is that you can’t try to sell them property—you offer them status, or a lifestyle, or a unique place in the sky. A marketing video for 432 Park Avenue, scored to “Dream a Little Dream,” features a private jet, Modigliani statuary, and Harry Macklowe himself costumed as King Kong. One recent morning, at the development’s sales office in the GM Building, Wallgren led me down a hallway lined with vintage New York photographs, through a ten-by-ten-foot frame meant to illustrate the building’s enormous window size, to a scale model of Manhattan.

“If you bend down like this,” Wallgren said, stooping to street level, “you can really appreciate the height of it.” The development will top out at 1,396 feet, making it the second-tallest building in the city. Wallgren pointed to a comparatively stunted model a few blocks away. “There’s One57,” he said. “It’s about 1,000.” (Left unmentioned were plans by One57’s developer Gary Barnett to build a 1,423-foot tower down the street.)

Wallgren’s team has taken its sales pitch to events in Moscow, Hong Kong, and Beijing. “The Carnegies and the Fords and the Motts, they made their fortunes in other parts of the country, but they all convened in New York,” Wallgren told me. “So it’s not new. I think what we’re seeing is a continuation of that phenomenon. It’s now expanding to other parts of the world that have new pockets of wealth.” While robber barons built Fifth Avenue mansions, the buyer of 432 Park Avenue’s top penthouse (asking price: $95 million) will get an observation-deck view of Manhattan.

Buyers for whom money is still something of an object—very wealthy people who have a few spare million to spend on a reliable investment—have slightly less lofty options. “This is classy stuff!” exclaimed Gennady Perepada, a broker who was showing me an empty Fifth Avenue condo one afternoon. He was crowing over the bathroom, which prominently featured a bidet. A stocky Ukrainian with thin, slicked-back hair, Perepada had found the apartment on behalf of an investor, whom he would only describe as “Russian-speaking,” who purchased it for $3 million. Perepada said his clients insist on confidentiality and instructed me not to identify our location, a popular one with foreign buyers. “Just say ‘classy building,’ ” he told me as we looked down on St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

“By the way,” Perepada added, “this apartment was sold by phone.”

Perepada, who lives in Sheepshead Bay, says he acts as a sort of all-purpose consultant and fixer for his moneyed clients, who hail mainly from the former Soviet Union. “Rich people come to the U.S., and these people are busy,” he said. “What is, for these people, very important? I am asking you! To save the time.” Perepada doesn’t drag his clients to a bunch of open houses. He takes them to Jean Georges, gets them hockey or Broadway tickets, rents helicopters or horse carriages, sets them up with plastic surgeons. He says that by building a rapport, he is able to sell 80 percent of his properties with a simple phone call.

We took the broker’s black Mercedes to another appointment, at a penthouse on the Hudson. “Did you see The Wolf of Wall Street?” Perepada asked as we drove. “I love this movie. You see how he works? Amazing. ‘If you trust me, you have to buy. If you don’t trust me, you need to work with someone else.’ This is my regulation: Trust me, take it.”

The further you descend in price, the more distanced the ultimate owner tends to become from the transaction. Million-dollar apartments are often traded sight unseen, based on a floor plan or a YouTube clip. Martin Jajan, a lawyer who is one of New York’s most prolific closers in new condo buildings, told me it is not uncommon for him to buy for clients he’s never met.

I spoke with Jajan at the café at the Trump Soho, the hybrid hotel-and-condominium project (his small firm has handled around 40 percent of the building’s sales). Jajan’s family is from Argentina, and his clientele primarily speaks Spanish and Portuguese. “In the ’80s or ’90s, Argentina was doing very well, and now here we find that the economy is moving further and further left,” he said. “Same thing is true of Venezuela.” For these clients, he said, New York represents “a plan B, in case things go further south.”

Jajan believes the most important service he offers is reassurance. “The client wants an adviser here; he wants to feel comfortable knowing he has someone he can trust here in the United States.” Jajan’s firm offers a range of management functions. “We recently purchased a vacuum cleaner,” he told me. “It was for one of our high-net-worth clients that bought $15 million worth of property this year. We’re not about to say, ‘We don’t do that, we’re lawyers.’ ”

But mostly, Jajan sets up corporate vehicles like LLCs. “Those structures can be simple or they can be complex, depending on different factors,” he said. While putting the deed in the name of a corporate entity has practical advantages—it can be part of a strategy to avoid estate taxes or potential lawsuits, a consideration for rental properties—the tactic is also designed to ensure secrecy. All he needs to do a deal is a simple corporate structure and a wire transfer to his escrow account. “Ninety-nine percent of the time,” Jajan told me, “they already have the money outside of their home country.”

Part IV: The Shadowy Part

Extreme wealth demands extremely elaborate wealth management, and anyone who has a few million in spare cash will probably already have an entrée to the cloistered world of private banking. An anonymous high-net-worth client of Credit Suisse, who spoke to U.S. Senate investigators after taking advantage of an amnesty for tax cheats, described the process by which he would manage his funds when visiting Zurich. A remote-controlled elevator would take him to a bare meeting room where he and his private banker would discuss his money; all printed account statements would be destroyed after the visit.

The theatrical secrecy is designed to build personal trust between such bankers and their clients, which is especially vital when the goal of the transactions is to conceal assets from the prying eyes of rivals, vengeful spouses, or tax collectors. Moving the money itself is a relatively simple matter: A wire or a suitcase can convey cash from China to Singapore, or from Russia to an EU member state like Latvia, and once the funds have made it to a “white list” country, they can usually move onward without triggering alarms. Concealing the true ownership of a property or a bank account is trickier. That’s where the private bankers, wealth advisers, and lawyers earn their exorbitant fees.

Behind a New York City deed, there may be a Delaware LLC, which may be managed by a shell company in the British Virgin Islands, which may be owned by a trust in the Isle of Man, which may have a bank account in Liechtenstein managed by the private banker in Geneva. The true owner behind the structure might be known only to the banker. “It will be in some file, but not necessarily a computer file,” says Markus Meinzer, a senior analyst at the nonprofit Tax Justice Network. “It could be a black book.” If an investor wants to sell the property, he doesn’t have to transfer the deed—an act that would create a public paper trail. He can just shift ownership of the holding company.

Recently, scrutiny from the United States has punctured some of the traditional secrecy of Swiss banks. But that has just pushed clients to boutique advisory firms, often run by the same personnel. “Banks like working with those firms,” Meinzer says, “because they are then legally in the clear, without the risk of going to prison.” As international blacklisting has pushed some offshore locales toward greater legal compliance, new havens have arisen. New Zealand trusts offer similar secrecy to those of the Caymans, without the stigma.

It’s a sophisticated, well-oiled system that rarely requires crude subterfuge. Though U.S. authorities track all transfers over $10,000, a wire into a real-estate lawyer’s escrow account should look perfectly routine. “A lot of times, I don’t even know where my clients are from,” says the lawyer Bruce Cohen. “But I know that certain countries are very careful about the money that leaves their country.”

There is nothing illegal—at least from the destination nation’s perspective—about sending money from an anonymous offshore bank account to purchase property in America. On the contrary, it’s an everyday occurrence. That is precisely why experts say that property investment is a favored route for money laundering, a crime that depends on the outward appearance of legitimacy. The laundering process typically happens in stages: Illegal cash enters the world financial system somewhere and is funneled into a maze of accounts and shell companies, a process called “layering.” Finally, at the other end, funds are integrated into a seemingly respectable investment—like a luxury condo.

Secretive corporate structuring is a key element in the process. Earlier this year, an international team led by Shima Baradaran, a law professor at the University of Utah, published an ingenious study of its mechanics. The academics sent emails to more than 7,000 firms around the world that offer incorporation services, posing as a variety of characters, like a politically connected Uzbek or a Lebanese representative of an Islamic charity. “We purposely made it as shady as possible,” Baradaran says.

The experiment’s results confounded conventional presumptions. It turned out that offshore locales like the Caymans were the most stringent about complying with international anti-money-laundering standards. It was easier to set up an untraceable shell company in the U.S. than in any country other than Kenya. The study found firms in business-friendly states like Delaware and Nevada were particularly “abysmal.”

No federal authority, not even the IRS, keeps track of the actual “beneficial” owners behind LLCs, and the more lenient states don’t even require much record-keeping by the firms that handle incorporation. Many of the service providers Baradaran’s team approached asked for no identity documentation and were willing to set up LLCs in even the most suspicious scenarios. Most surprisingly, Baradaran found that the suggestion of foreign corruption actually increased the likelihood that a provider would agree to do business. “It’s really a race to the bottom,” Baradaran says.

Lawyers, brokers, and other service providers fall into a category that money-laundering experts refer to as “gatekeepers.” An international organization formed to combat such financial crime has called for gatekeepers to be required to report suspicious activity, and some nations, like Great Britain, have placed disclosure requirements on attorneys. But no such regulation exists in the United States, and while financial institutions are tightly monitored under the 2001 USA Patriot Act, parties to property transactions have been given a specific exemption. “It’s a big hole,” says Louise I. Shelley, director of the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at George Mason University.

In 2010, Senator Carl Levin released the results of an investigation into the role of U.S. property in foreign corruption, highlighting cases like that of the son of the dictator of Equatorial Guinea, who bought a $30 million Malibu mansion. New York real estate often figures in such scandals. Ukrainian politician Yulia Tymoshenko has filed a civil lawsuit claiming a crony of the country’s ousted president moved tainted money into New York development projects, while her opponents claim, in turn, that she laundered money through the city’s real estate. In 2012, federal prosecutors seized a Trump Park Avenue apartment from the son of a Philippine general who had been convicted of taking bribes. A $1.6 million condo in the Onyx Chelsea, belonging to a former Taiwanese prime minister, was seized after it was tied to a corruption scandal.

Such cases are rare and laborious, however. “You have to prove the nexus between the corruption and the property itself,” says Jaikumar Ramaswamy, chief of the Justice Department’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering division. “Sometimes judges are skeptical: ‘Why are we are going after some foreign guy who did something in a foreign country?’ ”

One notorious international fraud case illustrates the difficulty of tracing laundered money that allegedly made its way to New York. In June 2007, Russian police invaded the Moscow offices of William Browder, an American investor who had fallen out with the Kremlin. Documents hauled away during the raid were allegedly later used to transfer ownership of three subsidiaries to a shadow company, controlled by a criminal ring with government ties, which then used sham lawsuits to run up enormous liabilities. Based on the fake losses, the ring purportedly applied for a $230 million tax refund, which was immediately approved by Russian officials.

Browder suspected the swindle was pulled off with the complicity of powerful government players and dispatched a Russian attorney named Sergei Magnitsky to investigate. Magnitsky was arrested and died in prison under mysterious circumstances, prompting international outrage. In 2012, President Obama signed the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act, imposing sanctions on a list of Russian officials and other alleged accomplices in the fraud. Meanwhile, investigative reporters at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, an Eastern European nonprofit, obtained leaked bank records that appeared to reveal the destination of some of the missing funds: 20 Pine Street.

According to the allegations in a civil complaint filed by federal prosecutors in Manhattan, the tax money was deposited into three corporate bank accounts and then diced up into smaller amounts and bounced around several Russian banks. Ultimately, about $50 million was sent to a pair of companies headquartered in the capital of Moldova. From there, a small portion, $857,000, was transferred into a Swiss bank account belonging to a company called Prevezon Holdings Limited, now controlled by the son of a Russian political figure. The company had many interests in real estate, including an investment in a venture with a Soviet-born diamond and property magnate named Lev Leviev—who also happened to be one of the developers of 20 Pine.

Starting in late 2009, Prevezon began purchasing units in 20 Pine, acquiring five in total. The company later added three Manhattan commercial spaces to create a $24 million portfolio, which prosecutors sued to seize last year. “While New York is a world financial capital,” U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara said in a press release announcing the action, “it is not a safe haven for criminals seeking to hide their loot.”

In reality, the 20 Pine case shows just how hard it is to police the flow of money into real estate. It took a vocal American victim, a diplomatic furor, and an act of Congress to get the authorities’ attention. And the seizure is far from assured. Prevezon’s attorneys contend that, despite the elaborate chain of events alleged in the government’s civil complaint, prosecutors have offered little explanation for the company’s supposed connection to the Russian tax fraud. The only link the complaint alleges is a pair of wire transfers amounting to less than $1 million, which Prevezon claims were made in the course of normal business dealings.

The best—though still fuzzy—global estimates say as much as $1.5 trillion in criminal proceeds is laundered each year. The United Nations figures that as little as one-fifth of one percent of that is ever recovered. Levin has proposed legislation to extend the Patriot Act’s regulations to real-estate closings and to require disclosure from LLCs, but the bill has gone nowhere. Real-estate attorneys say such rules would violate their legal privilege, and brokers insist the marketplace already provides an incentive to keep transactions clean. “No building wants to have people who have made illegal money,” says Mark Reznik, a broker at A&I Broadway Realty, a firm that primarily serves Russian-speakers. Reznik says he provides a “prescreening” service for developers. “They want to have some kind of filter,” he says. “Like somebody said, Karl Marx or whatever, if the capitalist is going to see a triple return, he’s going to close his eyes. But we are trying not to deal with scumbags.”

Prevezon has been liquidating its New York holdings, though the proceeds have been frozen by the government. Its remaining 20 Pine units are listed with A&I Broadway Realty.

Part V: The New Market

The concentration of foreign buyers at 20 Pine was the product of a miscalculation. Leviev and his local partner originally bought the property, an old office building, during a speculative fever in the Financial District. Betting that its proximity would appeal to young bankers, they converted the building and mounted a nightclubby marketing campaign, complete with a 24-hour sales office that featured a fashion-style catwalk. The branding was the work of Michael Shvo, a marketer and pneumatic figure of the bubble era. While Leviev’s involvement in New York real estate ended unhappily, with price cuts, lawsuits, and an ongoing investigation by the state attorney general, Shvo has made a comeback as a developer. He’s now involved in several high-profile projects, including a high-rise development on Thames Street near the World Trade Center, and he says he is targeting the foreign market.

I recently visited Shvo—a perma-tanned Israeli with an action-figure physique—at his Fifth Avenue office, which is decorated with pieces from his art collection, including a Playboy bunny by Andy Warhol and a hanging noose by an artist whose name escaped him. He handed me the glossy “concept book” for one of his slated projects, a condo tower in Soho. Its opening read: “Target market: global citizens.” Inside the 400-page book were interviews with worldly apartment buyers like “Joao R.” and “Marco D.” “When you look at the newer money in the world,” Shvo said, “newer money wants to buy new product.”

This theory is driving an enormous amount of luxury development across New York, but it is based on fragile assumptions and subject to unpredictable external factors. Will other currencies maintain their strength against the dollar? Will recent shakiness in the Chinese and Brazilian economies worsen? Will Vladimir Putin force Russians to return their wealth to the motherland? Russian brokers say their clients went quiet during the Ukraine crisis.

“How deep is the market?” asks Michael Stern, who is building a 1,350-foot-tall tower at 111 West 57th Street, designed by SHoP Architects. “I don’t know, and neither does anyone else.” But while no one can discern the ceiling on pricing, there’s a hard reality to the floor. Stern says that once land and construction costs are figured in, the break-even point for ultraluxury towers such as his is around $5,000 a square foot. In other words: On average, every inch of these buildings must sell for 30 percent more than Manhattan’s most expensive penthouse did a decade ago.

Some brokers and lawyers who deal with foreign clients say they have seen a recent softening at the top end of the marketplace, as all these new buildings compete for a group of buyers who are canny about supply and demand. “I’m thinking that some of those properties are not worth $20 million or $30 million,” says Andrea Fiocchi. Sales at One57 have slowed lately. Though 432 Park’s development team claims it has moved more than half the building’s units, there are persistent whispers about overly ambitious pricing and underwhelming sales. The developer recently brought in an outside firm, Douglas Elliman, to assist with marketing. And by the time 432 Park is completed next year, Stern’s building and others should be coming in right behind to compete for the same fickle pool of buyers.

But the boom, and potential glut, at the billionaire end of the market obscures the broader trend, the one that has pushed up prices for everyone. New development in New York has only slowly regained its momentum since 2008, and sales inventory remains mired near a decade-low point. The relatively rare new developments that offer apartments in Manhattan’s “affordable” price range, like 400 Fifth Avenue near the Empire State Building, are the ones that have proved particularly popular with foreign investors (400 Fifth Avenue has a large population of Chinese buyers). As of January, there were around 12,000 apartments in Manhattan’s development pipeline, but they will probably not come rapidly enough to change the equation for the foreseeable future. Competition will continue to drive the wealthy—foreign and domestic—to Brooklyn and middle-class buyers to despair.

“Especially in the condo segment, there really isn’t much to show buyers,” says Corcoran broker Frederico Gouveia. He deals primarily with Brazilian clients, and he invited me to tag along while he showed the available options to a banker from Rio. The Brazilian—a laid-back fellow who nonetheless asked for anonymity—said he was looking for protection against market instability at home. “The prices are crazy down there,” he said. “For me, it’s a big real-estate bubble.” As we set out from his Park Avenue hotel, Gouveia gave him a detailed financial breakdown of the eight condos he’d be seeing.

The Brazilian was focusing on the Upper West Side, and he wanted to spend between $3 million and $6 million. Within his price range, there was an odd duplex apartment decorated entirely in silver and a three-bedroom above Lincoln Center with a stunning view in need of major renovation. Quickly, the banker began to feel a gravitational tug on his expectations. He loved a place at the Aldyn, a new building on the Hudson that has drawn many foreign buyers, which was priced at $5.8 million. By the time he visited the sales office of the building in construction next door, One Riverside, he was saying his budget started at $4 million. Under the persistent charm of a saleswoman, he ended up perusing the impressive floor plan for an $8 million unit.

Even for the global rich, the most desirable Manhattan apartment is often the one that sits just a bit out of reach. As of now, Gouveia says the Brazilian is still looking.

Additional reporting by Ionut Stanescu, Paul Radu, Margot Williams, Mar Cabra, Titus Plattner, and Pavla Holcova.