Will Leitch: The first sport I wanted to bring up was the NFL, which has a disadvantage as opposed to baseball: It didn’t come of age until the TV era. So your main two New York superstars are probably Joe Namath and Lawrence Taylor. And LT was the best player of his time in his position.

Al Leiter: Lawrence Taylor was this guy who transcended his sport. Now, if we’re including what he did off the field, his drugs and his problems, I don’t know if he really is New York …

Leitch: Well, New York can often be about those things as well.

Steve Wulf: The thing that strikes me about LT is, not only did he bring linebacking to a whole different level, but that level hasn’t been matched or surpassed.

Joe Sheehan: He’s the end of a line, where he dominated defensively from the linebacker spot. The NFL in the eighties was more balanced than it is today. LT was the last guy who had a claim from the linebacker position to be the best player in the game.

Leitch: Maybe I’m wrong but it seems like now they’re doing the best they can to take the violence out of the game. The first thing we’re thinking about with LT is the Joe Theismann, and his hit on him, the most excruciating, disgusting thing you could ever see on a football field. And we loved him for it. He was a bad guy then, but kind of a likeable bad guy. Now you wonder if he would be on the cover of Sports Illustrated with the cover line “What is LT doing to football?”

Leiter: They wouldn’t allow it. With Conrad Dobler, I used to watch the Cardinals just to see if he would spit in somebody’s face or rip their helmet off. There was a dirty edge to the game. The money’s too great now–I think they honestly were working for a paycheck. Now they’re protecting paychecks.

Leitch: Joe Namath is the one that started that archetype of the New York athlete, where you have to have swagger, you have to have confidence. Every athlete that’s ever been a leader is always compared to Namath. Sanchez is a Namath; Jeter is a Namath. Do you think that he represents the city, regardless of his merit as a player?

Sheehan: Joe Namath didn’t invent that, Babe Ruth did.

Wulf: When you’re comparing Lawrence Taylor to Joe Namath, I think you’re comparing a great athlete in New York versus a great New York athlete. Are we looking for somebody who embodies New York, or the greatest athlete New York ever had?

Sheehan: I have to tell you, I’m not comfortable with Namath even being discussed next to some of these other guys. With all due respect to one great day in January 1969, he wasn’t a great quarterback. He didn’t have too long a career. If you make a listing of NFL quarterbacks, Joe Namath’s name is gonna come up very deep in the conversation.

Wulf: The one thing I don’t think we should lose sight of is how big that one day was. I mean, it was huge. It was not only a huge day for New York, but it was a huge day for the sport. It changed everything and that’s something we should keep in mind.

Leitch: What do you guys think of John McEnroe? He brought a New York attitude to tennis, a sport that is upper-crust and a bit snobbish. But he brought danger to it.

Sheehan: My memory of tennis was that it was going through a huge boom and I wonder how much of it was these staid personalities giving way to Jimmy Connors, McEnroe. I think you give McEnroe a certain amount of credit for popularizing a sport that had kind of been this country club turn up you nose event and mainstreamed it.

Leitch: Or, if it’s physical toughness you’re talking about, what about Mike Tyson?

Wulf: There was so much excitement when he was coming up. But it turned off so quickly. It left such a negative vibe.

Leiter: The most dominant boxer, definitely.

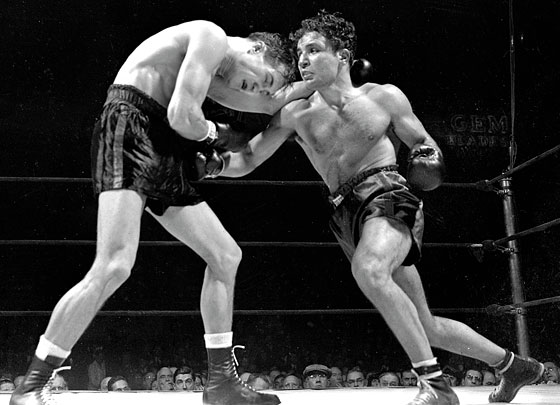

Sheehan: But when you say New York boxer, I think more of Sugar Ray Robinson or Jake LaMotta.

Leitch: What about a guy like Phil Esposito? At least for personality.

Wulf: Esposito used to have a Japanese Steakhouse on the Upper East Side.

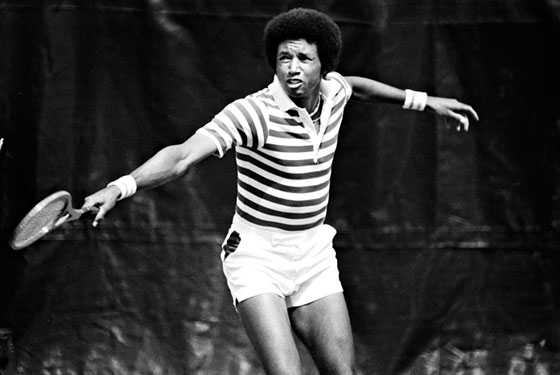

Leiter: Esposito was right in line with the whole Namath thing, kind of a cool cat. Long hair out in the street. McEnroe … could be. You had this great cool institution, and then this hothead New Yorker comes on the scene. But what about Arthur Ashe?

Wulf: He grew up in Richmond, but, yeah, he embraced New York.

Sheehan: The seventies were just great for that. You had Walt Frazier, you had Namath, you had Espo. Seems like you could be a New York athlete more than at any other time in history.

Leitch: A guy like Namath would get blasted by the press today.

Leiter: Anybody who wants to step out and be that guy would meet some resistance. Whereas, long hair and doing some stuff in Studio 54—it was part of the whole.

Wulf: You still made your life in the city then.

Leiter: That’s a great point. I think about Willie Mays, playing stickball in Harlem with the kids, all these guys who used to live and breathe with the borough. Then, later, there was some instinct to go and get this sprawling estate …

Leitch: Do you think that has changed the connection that maybe fans have to their teams?

Leiter: Players are insulated and separated: All of that has chipped away at the closeness that fans could feel. And there’s also the huge socioeconomic separation. In baseball, the guys will gravitate to each other with questions about “Where you living?” I’d been playing for about 10 or 11 years, and when my wife and I came to New York it was like, “forget that suburb crap.” The years that I was on the Mets, from ’98 to ’04, there were two to three guys who lived in the city. By the end of my tenure, we had about 10 or 11. But when I first got called to the Yankees, all the Yankee stars, starting with Ron Guidry and Lou Pinella had moved to New Jersey. Again it was, “Where are you living?” So as a new player, you think, “All right, good enough for Piniella, this guy, this guy, I’ll move to New Jersey.” And now the Yankees are in Greenwich and Westchester, and that started with Jimmy Key and Wade Boggs’s moving up that way.

Sheehan: And let’s not just associate this with New York. I think occurs across all sports and all cities now.

Wulf: My favorite story is from when Don Larsen pitched his perfect game. He used to hang out at a bar on Lexington Avenue, and all the regulars are really excited, and they go, “He’s not going to come in. He’s too big for us now.” And, you know, ten o’clock that night, here comes Larsen. One of the guys.

Leiter: David Wells did that once, and he got his face punched in.

Leitch: And we wonder why people don’t mingle anymore. Speaking of Don Larsen, though: Do championships matter? Patrick Ewing, who is seen as a failure by fans because he never won a title. They don’t consider him an all-time great, and a championship can all come down to John Starks having a bad shooting day.

Sheehan: And Patrick Ewing is a much greater player than, say, Bernard King. But when I think of the Knicks of my childhood, I have none of Patrick Ewing and a bunch of Bernard King. Bernard King was a fun player.

Leiter: He’s appreciated now more than when he played.

Sheehan: Ewing eventually grew into his own skin, but when he was 23 years old, he wasn’t a guy who was going to embrace New York, and then he’s on this team that’s terrible. Who are the athletes least suited to come to New York—the Ed Whitson list? Ewing might be on that.

Wulf: Unfair or not, the championship is a prerequisite to be in the pantheon.

Leitch: Why is basketball barely coming up in this discussion?

Sheehan: I think everybody else has caught up to a certain extent, developmentally. Globally, global basketball. It used to be you’d become a good basketball player in New York by going out and playing basketball every day. And even more so than baseball. This was true about basketball. There’s probably 50 hoops within a couple hundred blocks. But now basketball is about traveling teams and AAU teams and things like that and that’s leveled the playing field. When you’re getting recruited now, you’re getting recruited off of these traveling AAU teams, more so than playing with your high school. I think that’s impacted New York as much as any other source of talent around.

Leiter: If you’re not part of a championship team, there isn’t a lore. The fans just want it so badly. I think that’s why the whole LeBron thing happened. That’s the reality of what New York fans expect. It’s a drought of—how many years since the Knicks won?

Sheehan: Thirty-seven.

Leitch: And it’s been seven since the playoffs. Whereas in baseball, we practically expect to win.

Wulf: The Yankees have an awful lot to do with that. But everybody else has chipped in.

Leiter: I was on the other end of the 2000 World Series, as a Met, and I remember I desperately wanted the Yankees to beat Seattle, even though I knew it would be a tougher matchup, because I wanted to be part of a Subway Series.

Wulf: It’s so much harder for the Yankees to win now than in the past.

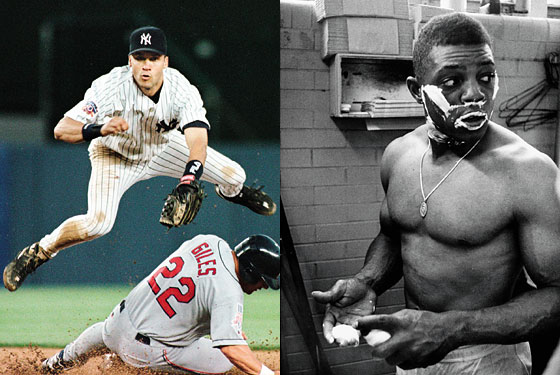

Leiter: No player movement, no free agency … So, if you look at his numbers and what he’s going to accomplish as a New York player, I want to talk about Derek Jeter. He’s here fifteen years—he’ll be the only player to ever, from start to finish, get 3,000-plus hits with the Yankees and surpass Lou Gehrig. His numbers aside from home runs are off the chart. He’s a champion. He’s a captain. He is an athlete. Babe Ruth had a lot of home runs, but it’s hard for me to imagine that chubby man running down a line drive to right center field. Making a dive to play. So I’m thinking about athleticism.

Wulf: I used to have this argument with Tim Kurkjian all the time, that the modern player is so much better than the old-time player. If you put Candy Maldonado in a time machine, he would hit 61 homers in 1927.

Leiter: Whether it’s fair or not, I see this big mammoth man that was overmatching everybody else like LeBron does. I’m with you on the impact: He saved the game, basically, from a time when the attendance was really poor.

Sheehan: They had to build a stadium that could hold 70,000 people.

Leiter: Whereas, with Joe DiMaggio, I’ve seen footage of him gliding through center field—if his career hadn’t been cut short, it might be him. So, instead of choosing Babe Ruth, I side with Willie Mays. Even though he’s only here in New York for eight years, he was, at that time and still to this day, talked about.

Wulf: I told my boss what I was doing this afternoon. He said, you’re going to vote for Willie Mays, right? I said he’s right up there but there’s somebody else I have in mind that I really want to push. An I told him the name and he said, “wow, that’s interesting.” I find myself siding with a guy with one of the most incredible careers in baseball history, and his entire life is contained within 25 miles of New York City. That’s Lou Gehrig. He went to Columbia. He was from Yorkville. He spent his entire life here. He played more games than anybody else consecutively. He did it as a Yankee. And I know this sounds silly, but whenever somebody imitates Lou Gehrig’s farewell speech, the thing that they miss is that he has a New York accent. That to me is the winning touch. He was the greatest athlete the Yankees may have seen.

Sheehan: If you’re going to weight some sort of New York heritage, I think it does push Gehrig up into the discussion. But Gehrig played his career in the shadow of Babe Ruth—up until 1934, he was basically second to Babe Ruth, not just in terms of performance but because of who they were as a person, and that carries a lot of weight to me 75 or 80 years later.

Wulf: It’s almost as if Babe Ruth was of the world and Gehrig was of New York. Plus Gehrig embodies all those other qualities of New York that we sometimes overlook. You know, the workaday athlete who goes to the ballpark and does incredible things and is often overlooked.

Leitch: Nobody ever overlooks Derek Jeter.

Sheehan: I think Derek Jeter is more beloved than even Yogi Berra was. You want to compare them at 35, I think Jeter is more beloved at 36 than Berra was at 36. A lot of Yogi’s legend is post–playing days: becoming the manager, getting fired, ending up with the Mets. Is Derek Jeter going to be Mickey Mantle, where he stays in the public eye and opens a restaurant and almost has a second career down the road? Or is he going to disappear and become a recluse like Joe DiMaggio did, other than the Mr. Coffee and the—

Leiter: I think he’d be more inclined to do that.

Sheehan: With Jeter, you have the whole stats-versus-guys-within-the-game thing. Is he a good defender? Is he a bad defender? Is he such a bad defender that he’s a bad player? I’ve been having these arguments for fifteen years about Derek Jeter. You forget that, even if he’s a bad defense or shortstop, he’s still one of the 30 greatest players in baseball history. And the championships do matter. If the Pirates took Derek Jeter in that draft, we wouldn’t be having this conversation, but they didn’t, the Yankees did. This guy is a first- ballot Hall of Famer.

Wulf: Here’s one simple matter of arithmetic for Derek Jeter. More Yankee fans have seen Derek Jeter than any athlete in New York history. He has played for a higher total of attendance than Ruth or Gehrig or DiMaggio or any of those guys. I mean, he’s played full houses for most of his career. The greatest compliment I can payJeter is that when I stacked him up against Joe DiMaggio, I went with Jeter. In some ways they embody the same kind of qualities that you love in a baseball player, but Jeter’s done it longer, and he’s been seen by more people.

Leitch: So we should start narrowing this down. It sounds like Babe, Gehrig, Mays, and Jeter are our final four. All baseball guys. So who’s your pick?

Leiter: For athleticism, I’d love to put Derek. But just when I think of the other greats, I’d have to say Willie Mays was the greatest New York athlete, even though he spent a period of time away from New York. When I talk to contemporaries of his, without a doubt Willie Mays is hanging off their tongues. I don’t know if you could say that about Derek. It was a period of time that he was beyond new York baseball or New York sports and I think the embodiment of the guy—you know, playing stick ball in Harlem—the absolute enmeshed community. I would like to say Willie Mays, reluctantly, but if I could do four, his name is Babe Mays Gehrig Jeter.

Wulf: I actually feel sheepish since we’re sitting on top of the Jackie Robinson Museum [Ed. note: The museum is in the same building as New York magazine’s offices, where this discussion was held.], but It’s pretty clear it’s a Yankee. I’m a Mets fan—I’m allergic to things Yankee. But these Yankees stand for the championships, for the excellence, for the way they carry themselves. So it really came down to Ruth or Gehrig or Jeter and because I weighed heavily the New Yorkiness of these athletes, I’m going with Gehrig. But obviously all three are great picks.

Sheehan: I’m closer to changing the vote I walked in here with than I thought I would be, and it’s mostly because of the arguments for Derek Jeter and Lou Gehrig. The fact that Gehrig spent his whole life here carries a lot of sway with me, though I think there’s something to be said for doing it in the modern era, the way Derek Jeter did. But Derek Jeter has never been considered the very best player in the game by his peers. I go back to the fact that Babe Ruth was the greatest pitcher in baseball and changed the game as a hitter. New York is the greatest city in the world, and the greatest New York athlete should be the greatest something, and Babe Ruth is the greatest baseball player who ever lived. Among those four—Ruth, Gehrig, Jeter, Mays—I don’t think there’s a wrong answer.

Leitch: Well, we have a vote for Mays, one for Gehrig, and one for Ruth. I’m persuaded by Joe’s argument: The only person we’ve talked about who can be called the greatest player in their sport is Ruth. And, as we’ve established, New York is about the best. Even if Al thinks he was a little chubby.

Sheehan: By the way? I’m brokenhearted the name Don Mattingly didn’t come up.

Leiter: I know.

THE ARGUERS

Will Leitch

moderator

Al Leiter

Yankees (1987–89, 2005) and Mets (1998-2004) pitcher; studio analyst, MLB network; commentator, Yes Network.

Steve Wulf

senior writer, ESPN The Magazine, and co-creator of Rotisserie League Baseball

Joe Sheehan

co-founder, Baseball Prospectus; writer for Sports Illustrated