There was a problem with the cookies.

When Jordan Metzner and Juan Dulanto launched Washio, it had already distinguished itself from other laundry and dry-cleaning services. There was no storefront, no rotating rack, no little pieces of paper to keep track of. Customers ordered their clothing picked up via the website or a mobile app, and it was returned to them not in a tangle of WE ❤ OUR CUSTOMERS hangers but in sleek black bags marked with the Washio logo, an understated silhouette of a shirt collar. The company called the drivers who completed these deliveries, usually in 24 hours’ time, “ninjas.” Still, the founders wanted to make sure their business stood out from the competition—that Washio established itself as the washing and dry-cleaning service by and for the convenience-loving, whimsy-embracing millennials of the New Tech Boom. “So we came up with the cookies,” says Metzner.

Inspired by Silicon Valley guru Paul Graham’s seminal essay to “do things that don’t scale,” they sourced cookies from bakeries in their three markets—snickerdoodles in San Francisco, frosted red velvet in L.A., classic chocolate chip in Washington, D.C.—which the ninja delivered, wrapped, along with the freshly laundered clothing. The gesture added another logistical wrinkle to an already complicated business, but it was worth it. “In the beginning, people loved it,” says Metzner. “Our social media went crazy, like, ‘Oh my God, Washio is the best!’ ”

That was in the beginning.

One Wednesday morning this spring, after staff at Washio had gathered for their daily “stand-up” meeting—a ritual suggested in the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, a 2001 work-processes manual that advocates keeping employees on their toes by having them give status updates literally on their feet—operations manager Sam Nadler broke some bad news. “Actually,” he said, “we’re starting to get a lot of requests for healthy treats instead of cookies.”

Ha, well, of course they were. Entitlement is a straight line pointing heavenward, and it should come as no surprise to Washio, where business is based on human beings’ ever-increasing desires, that their customers were upping the ante yet again.

Remember the scrub board? One imagines people were thrilled when that came along and they could stop beating garments on rocks, but then someone went ahead and invented the washing machine, and everyone had to have that, followed by the electric washing machine, and then the services came along where, if you had enough money, you could pay someone to wash your clothes for you, and eventually even this started to seem like a burden—all that picking up and dropping off—and the places offering delivery, well, you had to call them, and sometimes they had accents, and are we not living in the modern world? “We had this crazy idea,” says Metzner, “that someone should press a button on their phone and someone will come and pick up their laundry.”

So Washio made it thus. For a while, this was pleasing. But in the hubs and coastal cities of Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., and San Francisco—especially San Francisco—new innovations are dying from the day they are born, and laundry delivered with a fresh-baked cookie is no longer quite enough. There’s a term for this. It’s called the hedonic treadmill.

Fortunately, the employees of Washio are on their toes. “What if we did bananas?” Nadler suggested. Everyone laughed.

Metzner held up a small brown bag featuring a silhouette of a flower and a clean lowercase font. “I’ve been talking to the CEO of NatureBox,” he said. “It’s like a Birchbox for healthy treats. Every month they send you nuts and …”

“Banana chips?” said Brittany Barrett, whose job as Washio’s community manager includes cookie selection. Everyone laughed, again.

Metzner looked down at the bag. “Flax crostini,” he said. “I think it’s a much better value proposition than a cookie.” He looked at the bag again. “What is a flax crostini?”

We are living in a time of Great Change, and also a time of Not-So-Great Change. The tidal wave of innovation that has swept out from Silicon Valley, transforming the way we communicate, read, shop, and travel, has carried along with it an epic shit-ton of digital flotsam. Looking around at the newly minted billionaires behind the enjoyable but wholly unnecessary Facebook and WhatsApp, Uber and Nest, the brightest minds of a generation, the high test-scorers and mathematically inclined, have taken the knowledge acquired at our most august institutions and applied themselves to solving increasingly minor First World problems. The marketplace of ideas has become one long late-night infomercial. Want a blazer embedded with GPS technology? A Bluetooth-controlled necklace? A hair dryer big enough for your entire body? They can be yours! In the rush to disrupt everything we have ever known, not even the humble crostini has been spared.

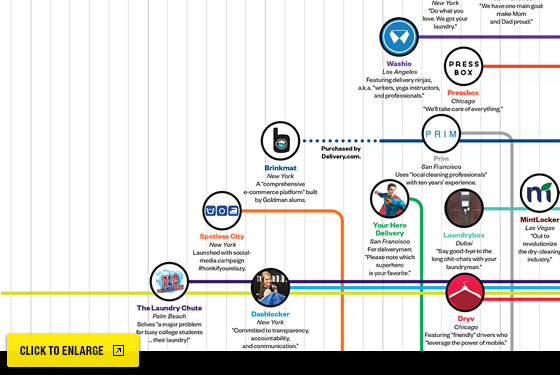

The Suds Cycle

Recent entries in the “laundry space.”

This was the atmosphere Metzner, Dulanto, and Nadler found when they arrived back in the U.S. in 2010 from Buenos Aires, where they’d settled after college and remained while America slumped into the recession. For kids in their early 20s, they had done impressively little screwing around. Dulanto, a Florida State graduate, had opened a juice bar, which is where he met Metzner and Nadler, friends from Indiana University who were opening a place called California Burrito next door. Two years later, Dulanto had opened a second juice bar, and California Burrito was a chain of 14.

But these accomplishments seemed meager when the friends returned to visit their home country. Things were very different from how they’d left them, and, like time travelers, they regarded the changes with awe. “Everyone had a Prius and everyone had an iPhone and everyone had Direct TV, and I was just like, Whoa,” Metzner says one afternoon this spring, sitting in the Washio break room, a sunny space in Santa Monica with an array of snacks and a fridge full of beer. “And I’m not, like, very materialistic at all,” he continues. “Like, I’m not a person who can’t live without my iPhone. But I’m thinking to myself, like, Wow, there’s a lot of life I’m sacrificing to live in this country.” At the time, Argentina’s wet noodle of an economy was foundering. Every day, California Burrito had to readjust prices to keep up with inflation. The conveniences his friends at home took for granted were a far-off dream. “iPhones were like $2,000. We were paying ourselves like $1,200 a month. And I realized that I was missing out on the great luxuries of the American lifestyle.”

Metzner flicks his brown bangs out of his eyes. At 30, he looks exactly like the now-grown-up actor who played the kid brother on Growing Pains, and in fact, he was a child actor of the same era, having starred in commercials and an episode of Tales From the Crypt before realizing that his innate showmanship was better suited to business.

Metzner and Nadler sold California Burrito and moved back home for good. Nadler enrolled in an M.B.A. program at MIT; Metzner went to L.A. and immersed himself in the culture of what a group of young entrepreneurs were calling Silicon Beach. He acquired a Prius, an iPhone, and a day job at a company that handles payments for video games; meanwhile, he went looking for opportunities in the tech space. It all went back to the iPhone, he realized. He may have been able to live without it before, but it was about to become indispensable.

“This thing, it’s alive,” he says now, holding up his phone. “It knows the weather, it knows what you like to eat, it knows your location, it knows what you like to buy.” He was particularly fascinated with the on-demand car service Uber, which was quickly building an empire on the back of smartphones. “We’re just going to see more and more businesses that we never would have seen before that exist on the premise that everyone has one of these in their pocket,” he says. “It’s like [Marc] Andreessen said. Software is eating the world.”

The question was, what areas of commerce remained undigested?

Metzner scoured TaskRabbit, the website on which the broke and eager underbid one another for the chance to do tasks for the moneyed and lazy, to see what services were most in demand. A lot of people, it turned out, wanted someone to do their laundry. “That spoke to me,” says Metzner, whose father sells discount clothing to retailers like T.J. Maxx and bestows on him a great deal of overflow, a luxury that inevitably becomes a burden. “I hate doing laundry,” Metzner says. “It’s my worst.”

That was one thing Argentina had over the U.S., he told Dulanto, who had sold his juice bars and was crashing on Metzner’s couch. The lavanderias. “These women would just stay there all day and do laundry, and your clothes smell incredible, they fold them perfectly, they package them perfectly.”

What if, Metzner proposed to Dulanto, they started a service where people could order their laundry picked up and delivered on their smartphones? Kind of like, he said, “the Uber of laundry?”

Of course, they wouldn’t have to actually do the washing. That they would outsource: to wholesalers, maybe, the types of cleaners used by hotels. They’d charge $1.60 a pound, and though they’d lose part of the margin, they could avoid the costs of rent and expensive machinery. And if they hired drivers on the Uber model—people who used their own cars and their own phones—there would be no need to buy and maintain vehicles. They’d just be the middleman, organizing the transaction and taking a slice of the profit—which, admittedly, was not huge with wash-and-fold. But once they had the laundry, the dry-cleaning would follow. Profits are higher on dry-cleaning, because who knows what dark alchemy is required to remove stains? No one, and everyone is willing to pay a premium to stay uninformed. The trick was to think big: “That’s where the numbers become exciting,” Metzner says. “Let’s do it in 50, 60 cities,” he told Dulanto. “Let’s literally go into every market.”

The competition, as they saw it, was negligible. “We kind of thought it was low-hanging fruit,” Dulanto recalls. Sure, plenty of people had their own laundry machines. But you know what people are like.

“It’s really kind of amazing the amount of anxiety laundry causes,” says Nadler, who came back from MIT to join Washio full-time and is completing his coursework remotely. “Like, it’s Sunday, and they just want to hang out on the couch, and they are looking at this big pile of laundry they have to tackle or else they aren’t going to have any clothes. I was talking to a classmate who said he and his wife were fighting because someone had to go to the dingy basement, and he felt bad because he didn’t want to send her to the dingy basement, but he was tired, and then someone needs to get quarters, and it just was a whole thing.”

In urban centers like New York and Chicago, many places offer delivery already. But: “The laundry and dry-cleaning industry, it’s all, like, old people,” says Dulanto in the nose-wrinkling manner of someone for whom aging is still an abstract concept. “They’re not tech savvy, and they still put up those really ugly stickers with that ’90s clip art.”

Convinced they were the only members of their demographic who had discovered this particular market inefficiency, they started to imagine a future of wealth and power. Maybe one day Washio would get bought by a larger company like Amazon, or Uber itself. Maybe they would strike out on their own. Go public. Use their delivery infrastructure to offer other products—maybe even overtake the Amazons and Ubers of the world. “But first,” Metzner said, “let’s, like, demolish laundry.”

The biannual clean show, formally known as the World Educational Congress for Laundering and Drycleaning, does not usually draw the young and overeducated. But this past June at the New Orleans Memorial Convention Center, a handful of flinty-eyed millennials in Bonobos lurked among the suits picked off the unclaimed-garment racks. Metzner was there. So were David Salama and Eric Small, the founder and head of technology of a fledgling New York–based dry-cleaning-and-laundry start-up called FlyCleaners, who had come to see if the industry was as technologically backward as they suspected. So far, the featured performance by viral sensation the Washing Machine Drummer Boy was the only thing they’d seen that placed them in this century. “There were only two technology-based things there,” recalls Salama, “and they were pushed off to the side.” As he paced the floor, Salama got a text from Small, who had ducked into a seminar called “Marketing Your Coin-Operated Laundry Business.” “He’s like, ‘David, all they keep saying is that the next big thing in marketing is having a website.’ And they were like, ‘If you really, really want to be advanced, you should have a Facebook page.’ That’s basically where these people are.”

Salama did a small inner fist pump. This was just the kind of inefficiency he’d sought to exploit as a trader at SAC Capital, the notoriously hypercompetitive Greenwich hedge fund where he’d worked after college. He’d left the job in 2008 after the market crashed and the atmosphere took a turn for the worse. “When times are good, it’s semi-poisonous,” says Salama, now 31. “When times are bad, it’s just outright hostile.” But just as he can’t shake his Brooklyn accent, he retains a certain amount of SAC muscle memory. “You’re trying to beat a market,” he says. “So you realize the importance of trying to think in ways other people are not.”

This had clicked last February, after Salama’s friend Seth Berkowitz had spent a good portion of the Knicks-Warriors game complaining about dry cleaners—no matter which one he went to, it was always a process; they were never open at convenient times; they took forever; and had he seen the Curb Your Enthusiasm where Larry David asked a senator for federal oversight of dry-cleaning? The entire industry needed to be disrupted. What they really needed, he said, was an Uber for laundry.

If it had been anyone else talking, Salama might have told him to shut up and watch the game. But Berkowitz’s offhand ideas had a history of working out. As an undergrad at the University of Pennsylvania, he’d started his own company, Insomnia Cookies, to fulfill the theretofore-unrealized desires of college students to have warm cookies delivered at two in the morning. It now has 50 outposts. And a few weeks after the Knicks game, Salama had quit his job to become the CEO of a company that would provide laundry and dry-cleaning on demand, by smartphone.

Ever since then, Salama had that unsure feeling in the pit of his stomach, the one he knew so well from SAC. “It’s always a little scary,” he says, “because often you’re swimming alone, but you have to retain confidence.” The Clean Show made him feel like he was swimming in the right direction. He called Berkowitz from the convention center’s floor. “This has got to be one of the few conventions left in America where technology is pushed off to the fringes and nobody is interested in it,” he told him.

Of course, this was not at all true. In reality, when people in a privileged society look deep within themselves to find what is missing, a streamlined clothes-cleaning experience comes up a lot. More often than not, the people who come up with ways of lessening this burden on mankind are dudes, or duos of dudes, who have only recently experienced the crushing realization that their laundry is now their own responsibility, forever. Paradoxically, many of these dudes start companies that make laundry the central focus of their lives.

Back in 2005, a San Francisco techie named Arik Levy founded Laundry Locker, which aimed to “change the way the world does laundry” by creating dedicated lockers where customers could drop off and pick up their clothes. “I’d tried to use the laundry-delivery services,” he says now. “But it was a nightmare. I’d have to pick a time slot, and then I’d have to wait …” In the past nine years, Levy has licensed the company’s “locker technology” to a host of other businesses, including Pressbox in Chicago and DashLocker in New York, which was founded two years ago by another SAC alum. Still, travel to a locker requires an effort some are not willing to make, particularly people who work in Manhattan office buildings and have acclimated to the luxury of restaurant-delivery websites like Seamless Web. Thus, in the winter of 2012, two rival laundry sites in the mold of Seamless launched simultaneously in New York. One was Brinkmat, founded by two Goldman Sachs software engineers. (“Like, ‘brink’ like ‘on the brink,’ ” explains founder Tim O’Malley, “and ‘mat’ like laundromat.” Awkward pause. “Names are hard,” his partner adds.) The other was SpotlessCity, the brainchild of corporate lawyer Hissan Bajwa, whose presentation at the 2012 TechCrunch: Disrupt conference was spirited but unconvincing. “Are you really solving a problem, or making it a simpler process?” one judge asked skeptically. “Well,” explained Bajwa, wearing a blue shirt with the company logo of a silhouetted iron, “the idea is you don’t want to pick up the phone, or lug around your stuff …”

One year later in L.A., Metzner, who is by his own account a “master schmoozer,” was cold-calling venture capitalists and getting the same kind of response. “This is a terrible idea,” one told him point-blank. It was a few months before the Clean Show, and Washio had launched, sort of. The founders were doing all the driving, although they still drew the line at doing any laundry themselves. (“Ugh, no,” says Metzner.) They were considering throwing in the towel—figuratively—when they got a break. “I think you need about $500K, and I think I know the people that can give it to you,” said a voice on the phone, as Metzner frantically Googled to figure out who he was speaking with. “Give me a couple of days.”

The voice belonged to Haroon Mokhtarzada, an early internet prodigy who had sold his build-your-own-website website, Webs.com, for $118 million in 2011. Mokhtarzada got Washio. He understood the indignities the company was trying to prevent. “You have to put your clothes in a car and drive them somewhere,” he says. “You have to take them out in public.”

Mokhtarzada had friends in the right places. He was tight with Shervin Pishevar, an early Uber investor and celebrity magnet Forbes had labeled a “superconnector.” When he got involved, “it was a game-changer,” says Dulanto. “We went from being the dork in high school to the hot girl.”

All of a sudden, Washio had $1.3 million—enough to afford a nice office in Santa Monica, spitting distance from shaving-industry disrupter Dollar Shave Club, dating-site disrupter Tinder, and Zuckerberg-disrupter Snapchat, with whom it started a soccer league. Washio did some hiring: engineers, an assistant for Metzner and drivers.

Since these were the main people interacting with customers, Metzner was adamant about being choosy. “I’m positive that we could go on Craigslist and post an ad for a delivery driver, and find plenty of people with crappy cars who would work for minimum wage,” he says, grabbing his laptop and flopping onto a couch in the Washio break room. “But I mean, you are going to get crappy people who don’t want to put their best effort forward and have a shitty vehicle that looks not nice. We decided to go a different route, where we can have premium people doing premium work.” He presses play on a promotional video of a pretty brunette in a Washio T-shirt, leaning against her black Mercedes. In Los Angeles, a lot of the drivers are actors, and their headshots are tacked on a bulletin board at the office. “That guy,” he says of one hunky blond we see picking up a bag of laundry to take out, “he could be in Twilight or something.” They chose the name ninjas in part to signify the company’s relationship to Silicon Valley, where the title is handed out freely. “It stems from Disney, which called everyone a cast member,” explains Metzner, in his stonery-didactic way. “All of these nameifications, or whatever, is basically to get everyone to think they’re not doing what they are actually doing, right? No one wants to be the trash guy at Disneyland. ‘No, I’m a cast member.’ At Trader Joe’s, they’re all associates. What does that mean? It means nothing, but I would rather be an associate than a cashier. It helps people elevate themselves and think they are doing something for a greater good.”

Washio does its part to sustain this delusion by pretending not to be a job. Every month, it throws a party for the ninjas, an open bar or a barbecue or bowling. “So they feel part of a community,” Metzner says.

Like the other enlightened start-ups it has modeled itself on, Washio would like to think of itself as making the world a better place, not just making a naked grab for market share. To that end, once a month the company brings clothing collected from customers by ninjas to a clothing drive organized by a nonprofit called Laundry Love.

“It’s really good,” says Nadler as we are driving back from a visit to the vast building where Washio gets its laundry done, largely by immigrants who are not invited to the open bars or barbecues. “It’s a bonding event for Washio-as-culture,” he goes on. “It’s good press. And it’s useful because it makes it easier for our customers. You know, because people always have things they want to donate to Goodwill, but then you have to go, and you have to organize it, and you have this bag sitting around forever—” He catches himself and laughs. “Actually, it’s not really that big a deal.”

Washio’s halcyon days came to a halt in July 2013, when Y Combinator, the country’s premier tech incubator, announced the launch of Prim, an on-demand laundry start-up by two Stanford graduates. To Metzner and Dulanto, it felt like a personal slight: They had applied to the incubator and been rejected. To add injury to insult, Prim was offering pickup and delivery for a mere $25 a bag—about half the price of Washio. And its logo? A silhouette of a bow tie on a blue background. Washio’s investors were nervous. “YC companies get a lot of attention,” warned Mokhtarzada.

The company needed to make a move, one that showed the tech community who the alpha laundry company was. In early October, Washio opened up shop in San Francisco. Not surprisingly, the area around Silicon Valley was already awash in laundry disrupters. In addition to Prim, there was Laundry Locker, along with three other locker-technology-enabled businesses: Sudzee, Drop Locker, and Bizzie Box. There was Sfwash, which offered ecofriendly cleaning on top of pickup and delivery. There was even, briefly, a service called Your Hero Delivery, whose driver-founders dressed like superheroes. (“At the end of the day, did we really want to spend our whole lives schlepping dirty laundry?” one of them told PandoDaily of their decision to fold. “No.”) Another upstart was about to launch: Rinse, whose founders described their business to a Dartmouth alumni newsletter as “an ‘Uber’ for dry cleaning and laundry.”

Metzner knew someone in common with the founders of Rinse, so he decided to give its CEO, Ajay Prakash, a call. Just to let him know his company was coming to San Francisco. And so forth. “It was, you know, a perfectly civil conversation,” says Prakash, which may have been what Alan Arkin termed a “business lie.”

“It’s really competitive,” says Minh Dang, a former Laundry Locker employee who saw the laundry boom coming and opened his own wholesaler, Wash Then Fold, to service all of the new businesses. “It’s man-eat-man.”

The companies weren’t just competing against each other and the existing infrastructure for customers; they were competing for vendors like Dang—the people who would clean the clothes. And here, the young men from Dartmouth were outmatched: “I had to tell them no,” says Dang. “I didn’t want to get into some kind of turf battle, man,” he says. “I didn’t want to fight over laundry.”

Just before the holidays came more unwelcome news for Washio. An article in TechCrunch announced that FlyCleaners, the New York City–based start-up, had raised $2 million from investors. Unlike its competitors, who required that customers pick a time slot—basically the old model, app-ified—FlyCleaners was offering its customers “true on-demand” service, Salama told the site. With the click of a button, they could summon one of FlyCleaners’ trucks to their location within minutes.

Reading about the West Coast’s boom in laundry disruption had sent Salama into Sun Tzu mode. “Once we identified the competition, it was a matter of learning about them and understanding their strengths and weaknesses,” he says. He had to admit that his competitors’ logos were, well, cleaner than FlyCleaners’, which featured a stopwatch filled with bubbles on a dark-blue background and looked vaguely like a snowman caught in a spin cycle. “Everybody says that,” he says.

Although they call their drivers FlyGuys and keep the office stocked with snacks, they’re more concerned with being seen as a business rather than a start-up. “We’ve done this in a New York way,” Salama says. “We have really gone at the technology, and we’re super-serious about it. It’s not like fun and games and slides in the office.”

While their competitors were elbowing one another in Silicon Valley, FlyCleaners had been scouring Silicon Alley for a team as tough and experienced as the founders themselves. Among its recruits was Brian Tiemann, a software engineer from Bridgewater Capital, the world’s largest hedge fund. “You were expecting laundry machines,” Tiemann intones from behind the Star Trek–like array of screens, when I enter FlyCleaners’ Flatiron offices on a recent visit. Blond and bespectacled, Tiemann is that rare breed of tech nerd who took a job at a hedge fund not for the money but because of the technological opportunities it afforded. From the looks of him, he doesn’t know from fabric softener, but he enjoys the logistics of getting laundry and dry-cleaning all the places it needs to go. Squinting at the screen, Tiemann types in a command, enabling a driver to avoid a traffic jam on North 6th Street in Williamsburg.

In New York, hiring drivers on Washio’s Uber-inspired model wasn’t an option. FlyCleaners had to use trucks, and because of the traffic and narrow streets, the trucks had to be efficient. They built racks for laundry bags, and Tiemann, whose hobby is pimping out cars for the Bullrun, the annual race in which billionaires in souped-up vehicles race each other cross-country, outfitted each one with a tablet that provides drivers with order details, alternate traffic routes, selective streaming from accident-mapping services, and direct communication with headquarters. With guys like this at the controls, mom-and-pops don’t stand a chance. “That’s the idea,” Tiemann says grimly, sinking back into his screens.

Team Washio was intent on staying in first place. Mokhtarzada began mobilizing the troops, and over the next few weeks, Metzner would be in his office, leading the stand-up meeting or evaluating the skills of a ninja interviewee, when he’d feel a ping in his pocket signifying an email from Shervin Pishevar, cc-ing him on a pitch to Jerry Yang, or Scooter Braun, or Nas. “The craziest one on the email chain,” Metzner recalls, “was Kanye.”

The next thing he knew, Metzner was at Ashton Kutcher’s house, presenting him with the idea of an Uber for laundry. “Mila [Kunis] was there,” he says. “She made snacks.” Kutcher’s investment through A Grade, his partnership with Ron Burkle, helped bring Washio’s total funding to $3.6 million. (“We were most impressed with Jordan as a founder,” the Two and a Half Men star said in a statement emailed by a representative. “With trends and consumers all leaning towards a [sic] increased level of connivence [sic] Jordan has targeted a new vertical that we believe in.”)

In Silicon Valley, where The Work of creating The Future is sacrosanct, the suggestion that there might be something not entirely normal about this—that it might be a little weird that investors are sinking millions of dollars into a laundry company they had been introduced to over email that doesn’t even do laundry; that maybe you don’t really need engineers to do what is essentially a minor household chore—would be taken as blasphemy. Outside mecca, though, there are still moments of lucidity.

Sitting in an upscale pizza restaurant in Santa Monica, the kind of place where the cuisine has been disrupted so many times it has pretty much reverted to its original state, Metzner takes a breath. “It’s always easy to say in hindsight?” he says. “But in the middle of it, you can’t really tell if you are in a bubble or if you are just in a successful time. Because, like, Facebook went out and paid $19 billion for WhatsApp. That actually happened.”

The waitress brings him a beer. “People with money are going to figure out ways to invest their money to make more money,” he says. “If you look at finance, like when credit-default swaps were huge, right, everyone was investing in that. And when subprime was huge, people were investing in that. Now, it’s Silicon Valley.” He looks up at the television above the bar, which is showing the Lakers game across town. A shot of Ashton and Mila, sitting courtside, appears onscreen. The chyron informs us they are engaged. Metzner tips his beer toward them in congratulations. He’s not worried. “It’s like Vegas,” he says. “The excitement of winning far exceeds the downside of losing.”

A few months after Washio landed in San Francisco, Prim, the Y Combinator start-up, folded. In an interview, the founders gave several reasons, among them increased competition for and with vendors.

Asked if he thinks Washio had anything to do with its demise, Metzner smirks.

“That’s one down,” Mokhtarzada told him.

And on my last morning in the Washio offices, Metzner is still feeling confident. “I think we have established ourselves as the clear market leader,” he says, draping his arm casually over the sofa. Washio’s Washington, D.C., launch had gone well. The company had brought on a Ph.D. in mathematics to work on its routing systems, and a group of Harvard undergrads was helping refine the ninja hiring system. More excitingly, Kutcher had gone on Jimmy Kimmel Live and talked up the company. “It was surreal,” Metzner says.

Not long ago, a friend of Nadler’s brought back a flier from South Africa advertising a company with a logo similar to Washio’s. And the previous night, Nadler had pulled him aside to show him the app for Dryv, Chicago’s Uber of Laundry. Their logo: a hanger, in silhouette. “It’s survival of the fittest,” says Metzner. “Eventually, these guys who think they can mimic will get frustrated, and they will go away.”

But these are times of great change. The hedonic treadmill keeps its steady pace, creating new desires, new niches, new competitors. In the coming weeks, the Laundry Chute, a Palm Beach–based start-up catering to college students, will raise $100,000 in seed funding. An on-demand laundry app called Cleanly, launched in New York last year, will expand operations, and one called MintLocker, which offers its customers cupcakes, will start up in Vegas. “Every day you see another one,” says Arik Levy of Laundry Locker, which itself has embraced delivery and is partnering with Deliv to provide a service similar to Washio’s. “Although,” he adds, “ours is about 25 percent cheaper.” He’ll have to contend with Brinkmat, the victor of the first laundry wars, which was acquired by Delivery.com and is now doing business under the much simpler laundry.delivery.com. Even the fogies are innovating: Zips, a discount dry-cleaner franchise, is developing an app that lets you watch your garment get cleaned using high-resolution cameras.

In Santa Monica, it’s time for lunch. Metzner flicks his bangs and goes to look for his assistant. As he leaves, I notice the screen on someone’s computer is opened to a website featuring a gigantic picture of a chocolate-chip cookie. Not an ordinary chocolate-chip cookie. It’s a chocolate-chip cookie shaped like a shot glass and filled with milk, the latest creation of noted baked-goods disrupter Dominique Ansel. “The best dessert ever,” the website, Sploid, enthuses in the headline. For now.