Amid the weeknight din of Ruby Foo’s, the hostess bore complimentary cocktails—a peace offering, for making Julie and Samantha wait twenty minutes for their reserved table. She offered one drink to Julie and one to … Wait a minute. Peering at Samantha, she said, “I want to give this to you, but …”

Samantha, who had just been listening to her mother describe what an “awful, awful slob” she was as a teenager, nodded toward Julie and said, “You should give it to her.”

Would Samantha have accepted the drink if her mother weren’t there? I wanted to know.

“I usually take it when she is here,” Samantha said. “Usually people never really think she’s my mom. She’s very young looking. People honestly more often think we’re lovers.”

“Did you say lovers?” Julie said, laughing. She tipped half of her daughter’s unsipped cocktail into her glass, the other half into mine.

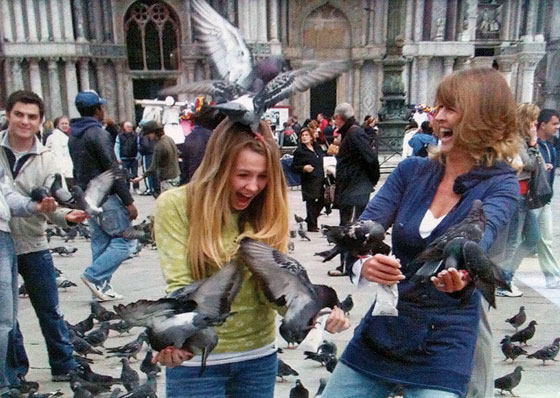

“Like, in Italy, people thought that,” Samantha said.

“We were probably clutching elbows or something.”

“Somebody whistled and I was like, Mom, we’re never touching in public again.”

But back to the drinks.

“Even if I’m not getting anything, I’ll sit at the bar with her,” Samantha said. “It makes me feel grown-up. I like feeling grown-up.”

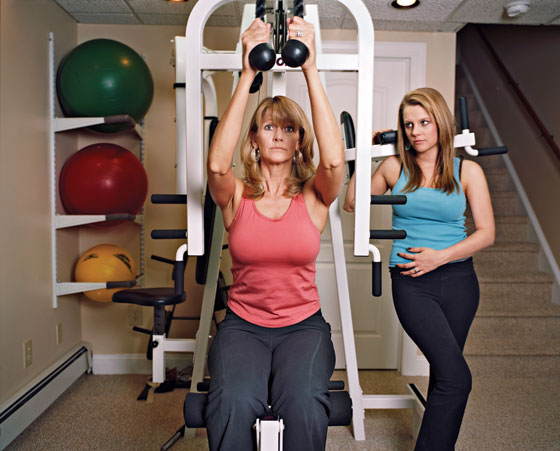

Julie, five-foot-ten and fit and blonde, had on a khaki Free People cargo coat and jeans and the form-fitting V-neck mother-daughter circle-of-love T-shirt Samantha had made a while back—half of a matching set, one for each of them. The shirt featured two slender figures and a heart floating in a womblike space. The figures weren’t holding hands, but almost.

Wearing the shirt on the same day was forbidden, though coincidences happened. Some mornings, Samantha and Julie met in the kitchen only to discover they were dressed in each other’s clothes or in nearly identical outfits, a variation on jeans, a white T-shirt, and a brown jacket, usually Urban Outfitters (Samantha) or Anthropologie (Julie), which Samantha calls the Urban Outfitters for adults. “Really, Mom?” Samantha says if they happen to twin up, though secretly she doesn’t mind. Her friends are all, “Your mom is so hot,” and her boyfriends look at Julie Bilinkas, who at 50 is a no-Botox knockout, and say, “MILF, right there.” Samantha’s like, “Great. My mom’s hotter than me.”

Samantha, 19, goes to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. She’s an actor. She talks like she’s paid by the word. Ideas and impressions bubble out of her. Her Twitter feed is a transcript of young energy unfiltered, a hybrid of early-woman savvy (“Let’s start these 8 pages of bullshit, shall we?”), earnestness (“I just want to be really, really good at something.”), id (“I’d like to punch you.”), and vulnerability (“I feel icky, Mom.”). @sambilinkas puts it all out there. Sometimes @juliebilinkas responds:

@sambilinkas: I just wanna be Marilyn Monroe.

@juliebilinkas: Marilyn Monroe is dead honey. I like you better as Samantha.

At one point at Ruby Foo’s, it occurred to me that the hostess had made an honest calculation when settling on her genre of olive branch. The gift of pretty drinks assumed a friendship. The cocktails said, “Enjoy your girls’ night out!”

And from a distance anyone might’ve figured mother and daughter for pals. Samantha refrained from the typical teenage indicators of mother-induced misery. No mortified slumping, no glassy stare, no snapping, no sighing, no episodic glaring, no thumbing out one cell-phone SOS after another. And Julie? When Samantha spoke, Julie listened until her daughter had completed her thought. Which I assumed happened only in dreams and completely unrealistic movies.

Seriously, was there no discord? They assured me that there was. Sometimes they fought “all day long.”

Over what?

Hmm. “Clean up your room?” “Don’t make me clean my room? I like my stuffed animals on the floor. I’m comfortable with my stuffed animals on the floor. Let me be me!”

I watched them closely. Humans are only so good at hiding jealousies and tensions, even for short periods of time. We all come with our little tells, and mothers and daughters are human control panels of buttons waiting to be pushed. There’s not a teenager alive who hasn’t considered her mom intolerable and embarrassing, or pretended not to know her in public, but based on what I was seeing, it was possible to achieve the opposite.

Watching Julie and Samantha felt a little like seeing a fantasy come to life. My mom hasn’t let me finish a sentence since 1975. We have never shared clothes. We do not text. She often e-mails me, hilariously, in all-caps, because it’s easier than finding the uncap key. Neither she nor I have ever uttered the word sex in the other’s presence. In fact, I’m positive my mom has never spoken the word at all. I now understand all of that; her parenting approach was a generational mandate. But sometimes, as a pre-Gilmore Girls teenager, I had this idea that mothers and daughters should walk arm-in-arm down leafy autumn roads wearing artfully knotted scarves, exchange gentle information on mean-girl management and boyfriends, and race home through the dappled sunlight to make cocoa. Once, in college, I tried to achieve this scenario with an aunt. It just felt weird.

Now mother-daughter BFFdom is a thing, having morphed its way onto the radar of sociologists, psychologists, authors, designers, marketers, and reality-show creators. The willingness to exploit one’s pubescent daughter for adult dating and fashion advice must be a Real Housewives casting prerequisite, and there’s no telling what the upcoming VH1 reality show Mama Drama will bring as it focuses on the turbo version of bestie mothers: “the partying parent who shares drinks, wardrobe, and social life with her daughter, and occasionally needs to be reminded that she’s the parent.”

Now that the phenomenon is here, it’s a little like watching the genie leave the bottle. You hope you’ve made the right wish.

There was a time in the not-too-distant past when mothers saw themselves as separate, as the standard-bearers of tradition and etiquette, and daughters saw their mothers as the people they dreaded becoming. As Good Housekeeping observed in 1917, “It used to be that girls looked forward with confidence to domestic life as their destiny. That is still the destiny of most of them, but it is a destiny that in this generation seems to be modified for all, and avoided by very many … The mothers of these modern girls are very much like hens that have hatched out ducks.” Parents didn’t even believe in comforting their children until Dr. Spock, in 1946, assured them it was okay.

The patterns really started to shift in the sixties and seventies, as Julie and her peers, the mothers of today’s teens, came of age during the women’s rights movement, the sexual revolution, and the Vietnam War. Breaking away from domestic and societal norms was, slowly, itself becoming the norm.

Still, nothing would have felt more alien, more preposterous, to most of those mothers than fully befriending their daughters, much less “friending” them. And vice-versa. I wasn’t yet a preschooler when Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was published, in 1970, but even when I was old enough to understand the concept of Teenage Softies, the book was still being passed around like contraband, as if we’d get in trouble if our mothers caught us reading it. Margaret, not our mothers, was the one explaining the more unvarnished aspects of our bodies, or any aspect of our bodies. Some of our moms happily let Margaret shoulder their work. Meanwhile they hoped to God that we had no questions.

Rare was the mother who seemed like one of us. I had exactly one friend whose mother behaved in a way that we associated with the capacity for “getting it.” She smoked, and she kept martini olives in the house, which sounded kind of glamorous. She hardly ever seemed to nag or be exasperated by her daughter. She’d light up a cigarette, cross her long legs, and ask me what’s up, as if I were a girlfriend who’d just come round for coffee. She seemed so cool I tried to change my first name to hers in fourth grade. Bought the personalized stationery and the press-on door plate and everything. The appeal wasn’t that she was more permissive than most moms—she wasn’t—it’s that she seemed to have a friendlier attitude toward her daughter. The antagonism didn’t seem to be there.

The following generation of mothers went ahead with complete freedom to reject conformity, to create their own parenting blueprint via an onslaught of self-help books and newly articulated mothering styles. (John Locke, in 1693, was hardly the last to put forth a strong thesis on how to raise a kid.) Mothers like Julie Bilinkas could choose from a widening set of ideas that allowed them to customize their parenting approach. With this came the notion, particularly among the middle-and-upper-class demographic, that children (and parents) most benefited from a more equitable relationship. Two-year-olds will never stop having tantrums, but befriending them early might spare everyone some of the non-hormone-related lock-out drama in the teen years: slammed doors, inexplicable sullenness. So went the theory.

Friendship became a kind of parenting strategy: By treating Child as Adult, parents hoped that the kid would actually become an adult, and a good one. The happy outcome for some: mothers and daughters who didn’t have to wait until middle or old age to actually enjoy each other’s company. To maintain peer-ness, there came a coinciding pressure to stay young, technologically supported by the capacity to stay young. Moms have never had at their disposal so many resources—so much paraphernalia—allowing them to shrink the generation gap. If they want, they can practically turn themselves back into teenagers.

In the nineteen short years of Samantha Bilinkas’s life, the world has lost its mind over the eminence of all expressions of youth, Abercrombie to OMG. The mother-daughter-besties development couldn’t have happened without the stay-young revolution. After the culture handed women the tools to look young, shop young, talk young, think young, it demanded that they do it then deluded them into believing they’d succeeded and needed to improve upon that success.

“I see women at the gym who I know are 50 and they look 20,” says Deborah Carr, a Rutgers sociologist and co-author of Making Up With Mom. “This moms generation—especially if they’re baby-boomers or Gen X—they’re such a part of this youth culture they don’t actually see themselves as the old mother.”

“I had a lot of patients saying, ‘My mom’s my best friend.’ I remember thinking, That’s because you don’t know any better or because there’s something really fucked up going on.”

Camilla Mager, a Upper East Side psychologist who specializes in women’s psychology, is talking about when she worked as a Sarah Lawrence College counselor. “The question you have to ask on some level,” she tells me, “is what’s going on in the relationship that two people of such different generations consider themselves best friends? As close as you may be to your mother, ideally on some level she’s always a guiding force, someone who’s been there before you; therefore you’re never peers. Not that mothers and daughters wouldn’t share things or that moms can’t speak to relationship issues, but you’re never actually on the same level. If you are, that suggests to me that the daughter is way too grown up or the mother is missing something in her life.”

You can see how it could happen, though. Think of a forced-closeness dynamic borne of family dysfunction, which is increasingly possible now that women are having fewer children on average and more are getting divorced. At one point I spoke to one mother-daughter pair who had forged a sophisticated if tensile friendship after suffering a husband-father’s relentless verbal abuse. When the mother talked openly and sadly about what a douchebag the husband-father is, the daughter, 15, did not disagree. Rather maturely she told her mom: “Well, you just have to get out of there.”

A more alarming example: women who seem to spawn in order to socialize. They give birth to their “best friends” and become so obsessed with mother-daughter mind-melding they can’t work out who’s in charge. “I feel like my daughter is my best friend right now—she’s only 2,” as one mom put it on Babble.com. “She is interesting. She is empathetic.” (She is 2!) “I know my husband is supposed to be my best friend, but right now he’s a close second,” the mother went on. “I worry what’s going to happen as she gets older and inevitably, healthily, finds her own ‘real’ friends.”

In their book Too Close for Comfort: Questioning the Intimacy of Today’s New Mother-Daughter Relationship, authors Linda Perlman Gordon and Susan Morris Shaffer report conversations with mothers who are proud of the friendships they’ve developed with their daughters but who worry the closeness has stifled their girls’ sense of self and independence. “Baby-boomer mothers report they learned to be resilient because they were less coddled,” they write. “Yet these same mothers say they responded to everything their children did by saying, ‘Good job!’ With this constant praise, they unwittingly gave their daughters unrealistic expectations of how the world should treat them; they neglected to give them a reality-based notion of their role in the world.”

As if seeing this coming, Julie Bilinkas wanted to achieve exactly the opposite. She tried to get ahead of negative outcomes by managing her relationship with Samantha early on. When Samantha got interested in performing at age 9, Julie, an operations executive, started driving her into Times Square every week for acting and voice classes. Each week’s drive gave them approximately two hours together round-trip, which comes to more than 1,000 hours of exclusive mother-daughter face time, give or take weeks off for holidays. Or for when Julie’s husband, Sam’s father, Barry, a former police detective, drove. Or when Samantha took the train. If something thorny was going on—boys, grades, etc.—Julie would save that topic for drive time and they’d unravel it together, Julie consciously trying not to hector or judge.

At first they focused exclusively on Samantha’s world. But as Samantha got older and they got closer, and as Samantha started showing a talent for listening and for administering advice, Julie started revealing information about her own life. She talked about how she’d learned how to respond to her husband when he was cranky (“Leave the room; let it blow over”) or about the challenges of managing employees (“Human beings don’t always fit into nice neat HR categories”). She says, “My mission was to raise a healthy, happy daughter. It just so happens that as she’s matured, we’ve discovered we’re quite compatible. I’ve gone through some stuff in my adult life where I’ve appreciated having her.”

Julie and Samantha spent so much of their early relationship communicating that by the time Samantha reached high school, it was no big deal for them to climb into the car and immediately begin dissecting a relationship situation or a friend’s pregnancy scare or corporate layoff concerns or a health dilemma. “When I think of us being BFFs, it’s not that superficial stuff like it is with my friends,” Samantha says. “It’s more of a deep friendship, not like, ‘Yeah, we’re best friends—we like to match, go to parties.’ ”

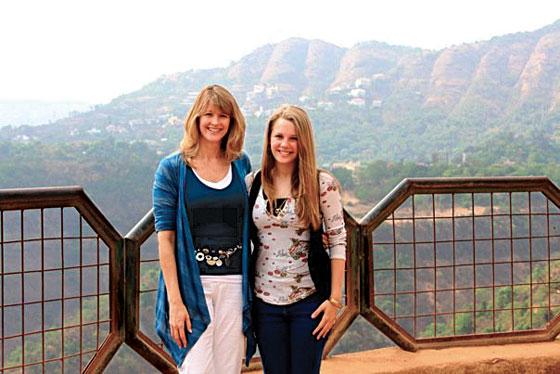

When Samantha was 13, Julie got bolder with her mothering moves: She’d pull her out of school for days at a time and take her along on international work trips. They shared hotel rooms in India, Italy, France, all over the world. By now Samantha has been to ten countries, and not just to the touristy areas—Julie makes sure to accept dinner invitations to colleagues’ homes so that Samantha will absorb and appreciate other cultures. “Traveling with her is better than being with a girlfriend,” Julie says, “because it’s killing two birds with one stone. I’m giving my daughter this really wonderful, enriching world environment, and we’re hanging.”

In their neighborhood of Randolph, New Jersey (the family also just purchased an apartment in the West Village so they have a place to stay when visiting Samantha at Tisch), some other mothers neither understood nor supported the fact that Julie had offered Samantha supplemental education in the form of real-life experiences through travel. Samantha watched them try to be protective “in the most loving way”—a daughter belongs at home; a daughter shouldn’t be going off shopping in Barcelona—but had no doubt about her mother’s approach. The peerlike construct wouldn’t work for everyone, but it worked for them.

It worked partly because Julie exploited a natural Bilinkas-family gender divide. Barry and son Billy had zero interest in travel. As much as taking Samantha on one-on-one trips around that world might look like favoritism, it wasn’t. Billy is a gamer, a computer guy. To try to bend him and his dad toward Julie and Sam’s interests—that, not leaving them for a week here and there, is what would’ve disrupted the family dynamic. The boys preferred staying home and eating frozen pizza, watching crime shows.

A tricky thing about being a legitimate BFF mother isn’t that the boundaries between mothers and daughters have shifted, it’s that they’re shifting all the time. Working in both friend and mother modes can get confusing on both sides. Samantha and Julie still bicker, sometimes over the fact that Julie keeps in touch via text with Samantha’s ex-boyfriends. “There are times when she wants to be a part of my life a little too much,” Samantha says. And when her mother reprimands her, “sometimes I don’t know how to handle that, because I’m used to her treating me more like an equal.”

Julie has had to stifle certain motherly instincts in order to preserve trust by saying yes when convention would demand a no. According to Carr, “In the old days, they said children should be seen and not heard; today’s parents want to see their children a lot.” To keep her daughter close, sometimes Julie has to keep her friend closer. In Barcelona, she allowed Samantha and a young cousin to shop unsupervised for an hour, swallowing her Natalee Holloway anxiety as she watched them walk away. The first time Samantha rode the subway in Manhattan alone and got completely lost, Julie said, basically, “Well, you’ll learn.”

Samantha likes to point out that a typical mother would’ve said, “You’re never going on the subway alone again,” or something like it. “That would have taught me that I’m not capable and that my mother is smothering me,” she says. “She lets me make my mistakes.” Her pride here is unmistakable. By rejecting the traditional traps, she and Julie have sort of beat the system by waging a new form of rebellion, one that’s not between parent and child but rather forged between them, against some standardized definition of family life. They’ve created their own dynamic, whether others understand it or not.

It will be interesting to see how far it will go. What will it mean to Samantha’s generation to be a good mother? Will there be an even more evolved form of invisible parenting that doesn’t resemble parenting at all? Already, Samantha is defining herself by what she would do as a mother, not, like so many others, by what she wouldn’t. “Corny as it sounds, I’m the kind of person who doesn’t care that I’m going to be like my mother when I’m older,” she says. Outside the restaurant, in the early-spring night, her trajectory already seemed clear. As they made their way through Times Square, it was hard to tell who was in the lead.

Barcelona, 2009 Photo: Courtesy of the Bilinkas Family

India, 2009 Photo: Courtesy of the Bilinkas Family

Venice, 2008 Photo: Courtesy of the Bilinkas Family