Eliot Spitzer, who hopes to be New York City’s next comptroller, likes to screw with his socks on—calf-length black hose, the atavistic shadow of sock garters visible in the mind’s eye. That Spitzer paid for sex is not actually all that interesting. That he brought his nerdish Dudley Do-Right public persona to bed with him seems a window to his soul.

On the spectrum of sexual taste, partially clad intercourse between consenting adults hardly merits a mention. It’s another jump to the writer Daphne Merkin, who confessed in print her predilection for being spanked, and Quentin Tarantino, who confesses his foot fetish somewhere in just about every movie. And these are miles from the 35-year-old law-enforcement officer who showed up in a psychiatrist’s office wearing Winnie-the-Pooh bib-overall shorts and smelling strongly of talcum powder, explaining that he liked to wear diapers, that he defecated and urinated in them, and who would, according to the doctor’s case study, “often think about ‘how I am a baby’ and masturbate in his diapers several times a day.”

Sexual self-discovery is a mysterious process, the only aspect of growing up that parents and teachers mostly leave children (if they’re lucky) to sort out on their own. The word groping works here. It’s you in the dark at first, maybe with props or pictures, and eventually with other humans, discovering over time—sometimes over a very long time—what gets you off, what turns you on. But how is it that you, being you, like this, not that? Why men, not women; why leather, not rubber; why dirty talk, but not dildos; why handcuffs, not horsewhips; why tongue, but not too much? And further, why do some people appear to be more sexually flexible, able to get off with men and women, orally and anally, while others—and this is true especially of men—remain fixed in their erotic preferences, able to achieve orgasm only during vaginal intercourse, only inhaling the scent of someone’s used bicycle seat, only looking at Internet pictures of children?

Freud would say that what he called perversions have their source in developmental stuckness: Something went wrong in the phases of childhood in which people learn to suck, poop, and get along with parents; psychoanalysis, the process of unsticking, would help them achieve something more like what once passed for normalcy (though even that normalcy, he thought, was an effort to recapture the satiated pleasure of breast-feeding lost after infancy). But in a world where Freud is bunk, what he called normal is now called “vanilla,” and “it’s complicated” is a Facebook status, the “why” question sits out there like a sexual itch, begging for an answer.

Evolutionary psychology, the explanation du moment for all human mysteries, offers a partial clue. To start with, people are animals, programmed for sex in order to produce more people. The chemicals released in the brain during orgasm—mainly dopamine and oxytocin—create a cycle in which hot sex begets more hot sex. The neuroscientist Jim Pfaus has discovered that if female rats have a long and satisfying mating session even in the most miserable setting (for them, a brightly lit box), they will continue to revisit the scene in the hopes of repeat action. If a researcher stops stroking a rat’s tiny clitoris with a tiny brush, she will bite the researcher’s sleeve, pleading for more. No woman who has ever continued to visit her hot boyfriend’s filthy bed, even after he ceases to return text messages, can fail to recognize the comparison.

Diverse sexual interests may thus be evolution’s way of helping humans to maximize the sheer amount of sex that goes on, matching desire for complementary desire and making sure we mix our genes up as much as possible. “We are preprogrammed to need diversity,” says Gregory Lehne, a psychologist at Johns Hopkins who studies human sexuality and gender identity (and the kind of person who is careful to use orientation to mean the people you love, taste to mean the things you like, and fetish to refer to an idiosyncratic preference that can turn compulsive and interfere with regular life). “Imagine if every person was turned on by the same thing, if every woman was turned on by George Clooney. The diversity of the human species requires that we be turned on by a whole variety of things.” Variety is a cosmic understatement—humans have a range of yearnings and cravings unmatched in the animal world. And when people are attracted to other people (or things) with no reproductive benefit, well, that’s part of nature’s plan, too—or at least an epiphenomenon of that plan. “Evolution has never required that everybody breed,” Lehne says.

But for all the insight evolutionary psychology offers about the benefits of variety to the species, even the newest and best research about how individuals acquire a particular kink says that it is not designed or determined by evolution, but that it happens, possibly arbitrarily, through childhood experience. Which un-banishes Freud and puts him back at the center of things—a supermarket-checkout version of him, anyway, less obsessed with mothers but still focused on childhood as the source of sexual taste in adulthood. There’s all kinds of research out there, pointing in all kinds of directions, but when it comes to a person’s individual kink, “the leaning is toward learning,” says Daniel Bergner, whose new book, What Do Women Want?, contains the rat study above.

But how do we learn? In Perv, forthcoming this fall, the science writer Jesse Bering describes a man passionately obsessed with amputees. The man himself traces his ardor back to a time when he was 5 years old, sitting under the kitchen table while a man and a woman were visiting for coffee. The woman had a plaster cast on her leg, and beneath the table, her husband kept stroking it. “When is it coming off?” someone asked, and in the boy’s mind, these oddball components—romance, thrill, leg, off—were translated in adulthood into erotic yearning. In Bergner’s previous book, the excellent The Other Side of Desire, he tells the story of an adman named Ron who grew up in Queens and remembers being fascinated, also at about age 5, by the woman who ran a dress shop in his neighborhood. He would urge his mother to stop by the store simply so he might revisit the thing that haunted him: One of the woman’s legs had been withered by polio, and she wore a special, stumpy shoe. As an adult, Ron was a serial amputee dater before finding happiness with a woman who modeled for magazines specializing in amputee porn. “The cherry on the sundae is that she’s a double amputee, which brings me such happiness and joy.”

A fetishist who finds his or her way to a therapist’s office can usually tell a genesis story about the exact time and place that an interest in a certain kind of person or costume or texture took hold (though shrinks warn that such retrospective certainty does not signal actual causes, and that these desires can intensify or wane over time). Rubber fetishists can often vividly recall the training pants their younger siblings wore. There is hardly a transvestite—defined in the literature as a straight man whose sexual arousal depends on wearing women’s clothes—who doesn’t remember being dressed up in his older sister’s bras and panties. Enema fetishists, for whom the ultimate erotic act is to be splayed across someone’s lap with a rubber hose in their rectum, are rarer than they used to be, says Lehne, but those that do exist tend to be older Jewish men of Eastern European descent whose mothers used enemas to force the issue when their little ones didn’t poo on cue. The Other Side of Desire contains the story of a man with a foot fetish so overpowering that he found it difficult to listen to the weather report in winter; just hearing the words feet of snow could make him hard. He confided to a therapist that in second grade, ashamed that he could not read, he looked down at the floor to avoid being called on. There, he saw his classmates’ feet.

Freud talked about a latency period in childhood, from about age 6 until puberty, barren of sexual feelings or thoughts. He was wrong about that: Kids aren’t having sex at that age, usually, and they aren’t thinking about sex as sex, but they’re having all kinds of experiences that establish the boundaries for what the mid-century sexologist John Money called their “lovemap”—the range of things they end up liking and wanting in bed. (The fact that children may begin to develop that map as early as 8 or 10 may seem a little less weird when you consider that, until recently, the age of consent for girls was 12 or 13.) But why do some things nest in your proto-sexual psyche, while others slide by? Lehne has a theory that the foundation for an individual’s sexual taste is built when an encounter with a particular image or event overlaps with an activation of the autonomic nervous system—a quickening of the pulse, a prickling of the scalp, a panting, blushing, whole-body rush of feeling. These are the sensations that adults usually recognize as sexual arousal, and shame, fear, anticipation, and anxiety are the closest most children get. Which may be why so many kinks have a nursery-school flavor, related to poop and pee and bare, naked bums; to wanting and waiting and finally having; to who’s bad and who’s good and who’s going to get in trouble later. Lehne saw one patient who fantasized about cutting the penises of young boys with a knife. In therapy, Lehne learned that his mother once found him masturbating in the bathtub at 7. “Don’t do that,” she said. “You’ll hurt yourself.”

The question is why some people who are caught masturbating at 7 collect a lifetime of neuroses, while others go on to a lifetime of jolly bath-time jerking-off; why only a few of the children who sleep with stuffed animals wind up dressing in furry-animal costumes with zippers at the crotch. A single child will encounter lots and lots of things that may hold an erotic charge—spanking, nuns, roller coasters, dogs, Beyoncé videos, gymnastic uniforms, X-ray technicians, UPS men, vinyl raincoats, the uncircumcised penis of the boy at the urinal. But why some people then go online in puberty to visit dog-porn or nun-porn sites is not fully understood—yet, anyway. One possible, if partial, explanation is that humans head into adolescence armed with many impulses, but in exploring them, even tentatively or in fantasy, find that some produce meager pleasures while others hit the jackpot, arousally speaking, and trigger a galloping obsession. Establishing sexual taste is “like carving a statue,” says psychologist James Cantor. “Discard the parts you don’t need, and you’re left with a structure.”

The bigger answer is that personality coalesces in a primeval swamp of nature, nurture, and culture, and sex is impossible to separate from all that. (The impulse to separate it is another holdover from Victoria and Freud.) In the scientific literature, there’s a whole category of sex offenders who are said to have “courtship disorders.” These are voyeurs, exhibitionists, the people who make obscene phone calls (or did, in the pre-Internet era), and frotteurs (the creepy guys who rub against you in the subway). Almost always men, they also almost always have social anxiety and get off doing solo the things that most people usually do ensemble. A voyeur named Barry described his craving to the Guardian earlier this year: “I couldn’t be in the company of a woman without trying to see what I could see, constantly thinking, I wonder what knickers she’s got on. I wonder what type they are.” In an effort to satisfy his need in a more socially conventional way, Barry asked a co-worker out, and, as the date was ending, he invited her to join him in the bushes. At which point he said, “I’m not going to touch you. I’m not going to do anything to you. All you’ve got to do is just undo your zip, and pull open your jeans.” The woman fled, and Barry was promptly arrested.

And how likely is it that your sexual tastes, the things that make you such a thrilling lay, are an unconscious assimilation of culture’s signals? Pretty likely, it turns out. The best working theory about the insane popularity of Fifty Shades of Grey is that it appealed to a certain type of woman, the overworked, exhausted female, for whom the notion of relinquishing control is the ultimate fantasy. The books worked on a second level as well: They turned soft S&M into something to talk about at the bar, which made it, in effect, fashionable. What you find sexually titillating probably depends as much on where you live and when you live there as it does on whether an amputee librarian taught you how to use the Dewey decimal system. Hairless genitals are the thing right now, whether you call them a taste or a fetish; but in the first part of the twentieth century, an earthy abundance of pubic hair was preferred. Foot fetishes increase during sexually transmitted disease epidemics, Ohio State researchers found in 1998; the Brits have raincoat fetishes; and the Japanese, for whatever reason, have a predilection for used schoolgirl underpants. In Israel, according to a survey by PornMD, porn surfers search prostate most of all; in the Palestinian territories, family; and in Syria—go figure—aunt.

Online, we live less in one of those cultural-sexual niches than in a cornucopia. The Internet offers unprecedented access to all kinds of sex, and the opportunity to connect with any person, anywhere, who likes what you like and who may introduce you to something, or someone, that you like more. (There’s even a Tumblr tag for vorarephiles, who get aroused imagining themselves being eaten or eating others; people post photos of pythons and super-magnified teeth and an animated version of what falling down someone’s gullet might look like.) But even online, conformity is the general rule. The narrative arc of the typical straight eight-minute porn tape is as predictable as a car chase: oral, missionary style, doggy style, anal, cum shot between the breasts or in the face. And while some tastes vary from place to place, within any culture there’s a basic consensus on what’s hot. In every state of the nation aside from Hawaii, MILF is among the top ten most-searched porn terms. A generation ago, MILF wasn’t even a word. Now it’s a meme.

But how do you account for a radical nonconformist like “Possum,” who, after a lifelong search, found deep domestic happiness with his two “mare wives.” He’d grown up in a city, in a family unmarked by stresses or strains, he told researchers who published his case study in the Archives of Sexual Behavior. Yet Possum knew from childhood that he was different from other kids. “I looked at horses the same as other boys looked at girls. I watched cowboy movies to catch glimpses of horses. I furtively looked at pictures of horses in the library. I tried to get interested in girls, but for me, they were always foreign, distasteful, and repulsive.”

Nevertheless, he married. He had two children. And he tried to stay away from horses, but couldn’t help himself, for the memory of his first time was just too powerful. At 17, he had found his way to a mare, and, after getting to know her, he climbed upon a bucket. “Breathlessly, electrically, warmly, I slipped inside her. It was a moment of sheer peace and harmony, it felt so right, it was an epiphany.” Eventually, he found the nerve to leave his wife and kids and live as he believes he was meant to live. “In the end, I found the right path, reached my destination, and now I am happy and at peace.”

There’s got to be a button or a switch somewhere, you think, a piece of human wiring that ordains a strong and anomalous sexual craving like Possum’s. It can’t be all nurture, right? There is evidence for this, though it has been discovered mostly among the extreme outliers. Alzheimer’s disease makes some patients both disinhibited and fixated on body parts—boobs!—that they may previously have taken for granted. And then there was the brain-tumor patient who suddenly developed a sexual love for children. When the tumor was removed, the pedophilia went away.

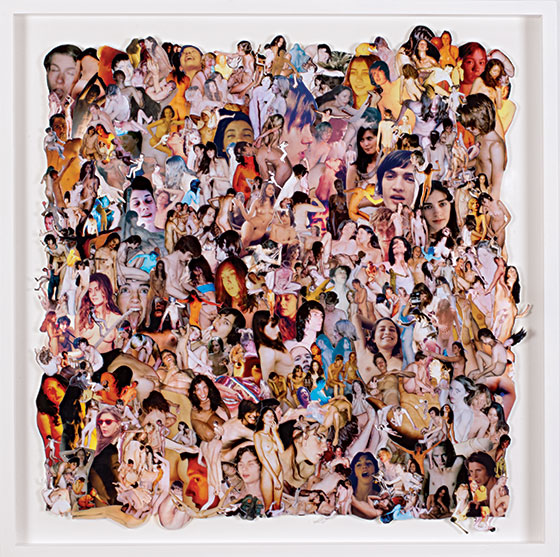

But consider the idle, innocent thoughts that run through your mind on any given morning: want to read, need to eat, have to, don’t forget, oh my God, that’s funny, that’s horrible, where’s my phone? Now think about sexual desire as equally rampant and unfocused—not a single, primitive, animal drive, but a wide, skittering sense of wanting. In the opening to his new book, Bergner describes experiments a researcher named Meredith Chivers is doing on women. She inserts a mechanism called a plethysmograph into women’s vaginas, then measures their arousal responses to a wide range of sexual images. Women, she has found, are turned on by just about everything: straight sex, lesbian sex, gay sex, intimate sex—even brutish sex between bonobos. “To stare at the data amassed by the plethysmograph was to confront a vision of anarchic arousal,” Bergner writes. And this is borne out by anecdotal experience: Everyone you know has probably done it with some range of fat ones and skinny ones, dumb ones and cute ones. They’ve probably done it clothed and naked, standing up and sitting down, with battery-operated devices and with the TV on and saying stuff that would make them blush in daylight. Think about what you’ve done, and then tell me, honest Injun, that you only like one thing.

Even objectophiles, a sexual-interest group whose members are turned on by inanimate objects, sometimes sleep with humans. The most famous of them are Erika Eiffel (née LaBrie) and Amanda Whittaker, who claimed as their lovers the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty. But object lovers also claim as their intimate companions more quotidian things: cars, trains, flags. Flags! In a 2010 paper by Amy Marsh, one man said that though other kinds of buttons moved him not at all, he loved fish-eye buttons so much that he sewed them into his underwear. Another loved soundboards: “We are very intimate in the bedroom,” he told Marsh. “We spend a lot of time in bed together, but my pants usually stay on.” The truth is the very abnormally weird are not so different, neurologically, from the regular, normally weird. Cantor suggests that an extreme sexual craving may be like a computer error in the brain; like Oliver Sacks’s man who mistook his wife for a hat, a person with a furry fetish sees plush and thinks “sex.” When lusting after someone, “your brain has to say, ‘This is a potential sex partner. And this is not—this is a tree.’ ” But to mistake a tree—or a giant plushy panda suit—for a sexy human, Cantor says, “is really a very small tweak.”