The night that Sotheby’s held its most successful auction ever, and slipped deeper into corporate turmoil, there may have been only three people who fully comprehended the paradoxical dynamic. One of them was performing for the other two as he brought the hall to attention with eight clacks of a hammer. “A very warm welcome to tonight’s sale of contemporary art,” said auctioneer Tobias Meyer. The handsome public face of Sotheby’s (and an imperious backroom power), Meyer exuded europäische cool as the first lot of the house’s big November auction, the Dan Colen painting Holy Shit, materialized on a silently rotating wall.

As the bidding opened, Bill Ruprecht, Sotheby’s long-serving chief executive, took a silent appraisal of his auctioneer’s work as he stood at the margins of the silvery audience. Some were buyers, some were sellers—in the delicate vocabulary of the auction house, “collectors” and “consignors”—but most were accustomed to trading enormous sums. More than any other institution, except perhaps its rival Christie’s, Sotheby’s has brought together the realms of art and finance, producing a lucrative friction. But now the system was under strain, its competition turned self-destructive. Ruprecht was facing intense pressure from restive investors—in particular, the third man in the equation, the hedge-fund manager in Row 8.

Dan Loeb, wearing a trim gray suit that night, is the public company’s largest shareholder. A few weeks before, he had likened Sotheby’s to “an old-master painting in desperate need of restoration,” claiming it was falling far behind Christie’s, and had demanded Ruprecht’s resignation. Though he is an art collector, Loeb wasn’t planning to bid. He sat at the center of the auctioneer’s field of vision, smiling jauntily, trading whispers with his wife and an art adviser, his mere presence signaling a challenge.

An auction is like a secret symphony, its surface spontaneity discreetly orchestrated. As Meyer conducted from his score—a coded book that mapped out likely buyers—few in the hall detected any disharmony. The auctioneer pivoted this way and that, coaxing with courtly invitations. “Shall we bid?” “One more?” Meyer hammered down a Martin Kippenberger for $6 million, a Jean-Michel Basquiat for $26 million, a Brice Marden for nearly $11 million—roughly ten times what the most valuable pieces by these artists fetched a decade ago. Christie’s and Sotheby’s auctioned $8 billion worth of art last year, according to an analysis by the firm Artnet, more than double their total from 2005, and the majority of that growth has come from their burgeoning contemporary sales.

“Contemporary,” in the art market’s taxonomy, is a category that encompasses everything from long-dead mid-century artists, like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, to 28-year-old Oscar Murillo, who has lately been racking up impressive auction numbers. As a sector, they are united by their rapid price appreciation, which has made contemporary art the center of a ferocious battle between Christie’s and Sotheby’s. The two major auction houses must replenish their inventory twice a year, for big events in the spring and fall. The night before the Sotheby’s auction, Christie’s—a private company owned by a billionaire—had featured a selection that included Francis Bacon’s triptych Three Studies of Lucian Freud and an enormous Jeff Koons statue, Balloon Dog (Orange).

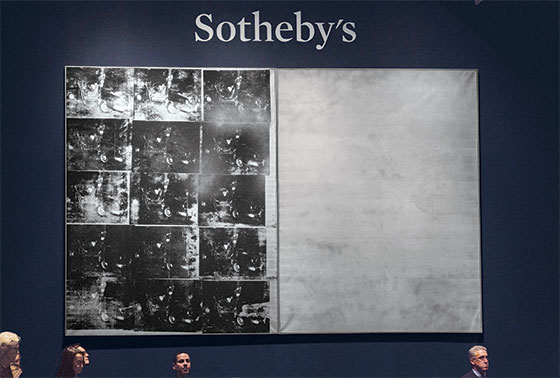

Sotheby’s was countering with its own trophy. “Which leads me to my favorite,” Meyer purred as he reached Lot 16. “Andy Warhol: Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster).”

On the wall to Meyer’s right was an enormous black-and-silver image of carnage, a silk-screened painting he pried from a collector after painstaking courting. “Let’s start the bidding at $50 million,” Meyer said. Within a minute, the price had surpassed Warhol’s auction record of $71 million. Ruprecht peered over a bank of specialists on telephones, plying clients on the other end of the line to go another million higher. Meyer flipped the gavel, small and rounded like a paperweight, and slowed his cadence as the stakes increased. “I shall sell it then,” he said, “for ninety … four … million … dollars.”

When Meyer brought down the hammer, the hall applauded. Counting the percentage fee that Sotheby’s charges buyers, the price was $105 million—a crowning triumph in any other season. But the figure paled in comparison to the sum Christie’s had fetched the night before for the Bacon triptych: $142 million, an auction record. The Sotheby’s auction would end up tallying a total of $380 million, making it the highest grossing in company history, but just over half the $690 million Christie’s brought in. And so the most remunerative night of Meyer’s selling career was also a disappointment.

Even if he’s not always buying, Loeb likes to attend auctions to conduct market research, to see what is selling and who is bidding—“to feel the market,” a confidant says. Midway through the Sotheby’s sale, though, he had felt enough. Loeb stood up, shot a quick glance toward Meyer, and turned and strutted out the center aisle, missing the conclusion of what turned out to be a final performance. Nine days later, Sotheby’s announced Meyer’s departure, a sudden move that left behind internal disarray and much speculation about its connection to the tense standoff between Ruprecht and Loeb.

Over the following months, Sotheby’s management negotiated with the hedge-fund manager, offering concessions, including a board seat, if Loeb would quiet down his agitation. Then, late last month, Loeb pulled his trigger, announcing that he and two allies would be fighting for three seats in a shareholder election scheduled for May. The move set off a battle between the Sotheby’s Old Guard and a financier who views artworks as financial assets that trade in a market made by the auction houses. The confrontation figures to get bitter and bruising between now and May, but at its center there sits a rather more exalted question: How do you properly value art?

As an investor, Loeb likes to buy a stake in a company, force internal changes, and sell once the share price rises. He is what is known in finance as an “activist,” but the word doesn’t quite capture his aggression. He is famous for his scorched-earth tactics; his weapon of choice is a cutting letter addressed to management, often full of embarrassing internal details dug up by private investigators. “Sometimes a town hanging is useful,” Loeb once told the magazine Bloomberg Markets, “to establish my reputation for future dealings with unscrupulous CEOs.” He forced the resignation of one target, Yahoo’s Scott Thompson, by revealing he had falsely claimed a computer-science degree. He dubbed another his company’s “Chief Value Destroyer.”

Brutal as they are, Loeb’s diagnoses are often correct, which is why his hedge fund, Third Point LLC, now has $14 billion under management. He likes to say he sees himself primarily as a research analyst, but when it comes to Sotheby’s, his point of view was also shaped by his personal experience as a collector. Though Loeb declined to comment for the record for this article—he prefers to speak through his letters and delight in the ensuing media frenzy—he has made his views clear over the past few months in many conversations with dealers, collectors, and other denizens of the art world. He sees contemporary art as an expanding economy and thinks that Sotheby’s stock offers the only public route to investing in it. He says he just wants the company to more creatively leverage its powerful brand and prime position in the art market.

In his October letter to Ruprecht, Loeb accused the CEO, who was paid $6.3 million in 2012, of presiding over a “lackadaisical corporate culture” where senior executives “live a life of luxury at the expense of shareholders.” But Loeb’s argument went beyond the usual activist-shareholder complaints about waste and inefficiency. “There is a demoralizing recognition among employees,” Loeb wrote, “that Sotheby’s is not at the cutting edge.”

Loeb claims that Ruprecht has been slow to recognize the “central importance” of contemporary art. Like many other hedge-fund managers—Steven Cohen, Ken Griffin—he is an avid contemporary buyer, and though he is not in the topmost tier of collectors, he has a respected and growing collection. Instead of hoarding masterpieces like treasure, as collectors did generations ago, the hedge-fund guys tend to treat artists like growth stocks, preferring those not yet judged by posterity, because that’s where there’s room for major price appreciation. Economists have found that over almost any period, art’s returns have trailed the S&P 500. But what if you were the person who bought a $7,000 painting by Murillo in 2011 and flipped it at auction last September for $400,000, or the one who bought a Basquiat for $1.6 million a decade ago and sold it for $25 million last June? The rewards can be enormous for those who have an edge. It’s an opaque market, where secret side deals, price manipulation, kickbacks, and collusion are an everyday facet of business. It rewards inside information, and since the market is largely unregulated, players can trade on it without any fear of legal consequences. That’s fun.

Auctions are the primary engine of the market. The houses act similarly to exchanges, bringing together buyers and sellers and making income from commissions. Typically, if bidding on an item fails to meet a (secret) predetermined figure, the item is “bought in” and returned, at little cost to the house. If the item sells, the house collects fees from two sides: Consignors pay a 10 percent commission, while buyers are assessed an additional “premium,” currently between 12 and 25 percent, depending on the size of the bid. At least, that’s how the system is supposed to work on paper. In practice, everything is negotiable, and much is obscured (oftentimes including the identity of the seller and the buyer). Still, anyone can bid, and the price is publicized, which makes auctions the only open portal to the marketplace. Private dealers, by contrast, keep their prices secret and tend to frown on open speculation. Those who represent living artists tightly manage supply, selecting buyers according to subjective assessments of status. This can be maddening to those outside the circle—especially to Wall Street collectors accustomed to being able to purchase pretty much whatever they want.

Loeb’s reputation in the art world was shaped by an episode a decade ago when he went to war with the dealer Barbara Gladstone over a diptych by Matthew Barney. He thought he had an agreement to purchase it, but Gladstone pulled it back, and Loeb, then merely a millionaire, was enraged at the slight. “It is not my intention to intimidate or frighten you,” he wrote a gallery employee. But in a series of emails to her and Gladstone, Loeb explained his fund’s methods of investigation, threatened to dig into the gallery’s sales practices and tax compliance, suggested he might share any information he uncovered with the press or “proper legal authorities,” accused Gladstone of “arrogance and lack of honesty,” and promised that he would be selling another work he had recently purchased from her gallery at a Sotheby’s day sale—a major kiss-off.

“I am sure that your first reaction will be to demonize me,” Loeb wrote, “but in time, I hope you will learn something from my work that will make you a better person.”

The emails were forwarded around the art world, and for a while, Loeb is said to have been blackballed by some dealers. But time and money have healed many wounds. Gladstone says she and Loeb are now friendly: “It was an unfortunate incident at the time, and we’ve all moved on.” During the 2000s, the dealer Larry Gagosian invited Loeb and his wife to meet artists at dinner parties. Loeb bought a Koons statue of a turquoise egg from Gagosian and decorated Third Point’s offices with works by Richard Prince. His style in art, as in business, can be confrontational: One piece he has exhibited, a Kippenberger sculpture of a crucified frog, was condemned by the pope when it traveled to Italy. Loeb has amassed a portfolio of the German artist’s work. “He thought that Kippenberger was a market that was undervalued,” says Loeb’s longtime art dealer and adviser, Christophe Van de Weghe. “He was proved right.”

Van de Weghe says that Loeb analyzes his art purchases the way he would any other investment position. “Dan is one of these guys that, if I offer him a painting, he will rip that painting apart,” the dealer says, breaking down pricing trends and looking for what investors call hidden value. “He has operated in the art world in the manner he operates in the stock market,” says Todd Levin, director of the Levin Art Group.

Loeb’s positions don’t always pay off. After Third Point was hit hard in the financial crisis, he liquidated some of his collection. The Koons egg—which Loeb had attempted to sell before the crash for a reported $20 million—fetched $5.4 million at a Sotheby’s auction in 2009, less than its low-price estimate. But Third Point has since bounced back, as has Loeb’s purchasing. In November, he was reportedly the winning bidder for a $46 million Rothko at Christie’s.

Many presume Loeb’s interest in Sotheby’s is motivated by ego or a desire to elevate his importance in the art world. Others believe he just loves a fight. “He’s a guy with billions and an ego to match,” says one art-industry consultant, “and he goes around breaking the crockery.” But another collector has a more direct explanation. “I think a fair amount of what Dan speaks about is probably true,” the collector says. “They are a pretty intransigent, stuffy old company at their core.” To a hedge-fund manager who prizes the power of information, Sotheby’s appears to be sitting in an ideal spot between buyers and sellers. Really, Loeb wants Sotheby’s to capitalize on that centrality by operating more like he does—taking positions, using leverage, and weighing risk and reward more aggressively.

The argument that Sotheby’s is insufficiently entrepreneurial would come as a surprise to a lot of people in the art world, who view the auction houses as the fount of all commercialism. During the 20th century, it was Sotheby’s that played a transformative role in the art market, dragging a monkish trade into the capitalistic sunshine.

The company—the oldest listed on the New York Stock Exchange—traces its ancestry to the 1700s and a bookseller who started out selling his wares in taverns. Over the centuries, in competition with Christie’s, it developed a business selling off the estates of the English aristocracy. But if you wanted to set a place and date of birth for the art market as it exists today, it would be a Sotheby’s showroom in New York on October 18, 1973.

A wealthy New York scenester couple, Robert and Ethel Scull, sold off a collection including works by Warhol, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Rauschenberg, reaping $2.2 million, about $12 million in today’s dollars. The sum was considered ludicrous, and the art world was scandalized by the Sculls’ profiteering. Legendarily, a drunken Rauschenberg confronted Robert Scull after the auction, accusing the collector of making tens of thousands of dollars from paintings the artist had sold him for a few hundred. “There was some pushing and shoving,” says David Nash, the Sotheby’s employee who staged the sale, now a private dealer. “Things have changed massively since then.”

Today, the Sculls’ speculative model is one many collectors emulate. And it’s the public-auction spectacle that drives valuations. Back in 1973, the auction houses functioned primarily as wholesalers, doing business mostly with galleries. During the 1980s, they started selling directly to wealthy buyers. A social-climbing shopping-mall developer, A. Alfred Taubman, mounted a corporate takeover of Sotheby’s and set about marketing fine art, as he famously put it, like a “frosted mug of root beer.” The auction houses began printing glossy catalogues and staging sales as if they were society balls.

Taubman discerned in auctioneering the potential for a “retail business without inventory.” But his low-risk, high-reward model never quite functioned as designed, because in order to project dominance in the field, the auction houses were always jockeying to win the most valuable artworks. This gives some sellers the power to dictate terms. In a hot art market, sellers who come to the auction houses for the traditional reasons—“the Three D’s,” death, debt, and divorce—are joined by profit-takers, who are in a position to exert superior negotiating power. The competitive pressure forces the houses to bargain away many of their fees. “Every time this has happened in the past, it has been a harbinger of the top of the market,” says Kathryn Graddy, a Brandeis University economist. “The auction houses get nervous, worried about market share, and they start doing things that have not been such a good deal.”

The 1980s art boom is reminiscent of today’s, albeit with different characters: Vincent van Gogh instead of Bacon; corporate raiders instead of hedge-fund managers; the Japanese instead of the Chinese and Qataris. When the crash came, in 1990, the Impressionist, modern, and contemporary markets all lost half their value. Sotheby’s and Christie’s, hit hard, struck a deal to eliminate the seller’s-commission discounts that were cutting into their profit margins. Prosecutors discovered the illegal conspiracy, and the two houses ended up paying $560 million in penalties. Taubman served nine months in prison and eventually sold off his controlling stake in Sotheby’s.

Bill Ruprecht assumed the chief executive’s office in 2000, in the midst of the price-fixing scandal. A doughy Midwesterner, he had started out in the rug department, near the bottom of the auction house’s rigorous class hierarchy. Todd Levin, who worked at Sotheby’s around the time, says Ruprecht initially looked like an interim caretaker: “He appeared to be this steady company man but an uninspired choice.”

The year Ruprecht took over, Sotheby’s reported a loss of nearly $200 million. He shut down a hemorrhaging e-commerce venture and sold the company’s York Avenue headquarters to developer Aby Rosen, a major collector. He divested the Sotheby’s real-estate brokerage business, selling a 100-year trademark license. The decisions had long-term consequences. To this day, Sotheby’s has no significant online-sales strategy, and with real estate off-limits, it has struggled to reproduce its brand-extension success in other areas. The company was forced to buy back its building after Rosen put it up for sale in 2007, paying $200 million more than it had received a few years before. Nonetheless, Ruprecht is credited with managing to stabilize the company.

Around 2005, the art market began to inflate. Between 2005 and 2007, Sotheby’s auction sales doubled, its profits tripled, its stock price quadrupled, and Ruprecht collected more than $21 million in salary and bonuses. Once again, however, an unhealthy dynamic took hold as consignors played the auction houses against one another. This time, it wasn’t just commission discounts they demanded—it was up-front price guarantees. Often transacted well in advance of a sale, these commitments transfer risk from the consignor to the auction house. Sotheby’s doubled the amount of guarantees it offered consignors from 2006 to 2007, to $900 million. At the time, paying up front for inventory was profitable for the houses, because if the bid exceeded the guaranteed value, they usually kept part of the excess. Then the financial crisis hit, and the bets soured.

After losing some $80 million on such transactions in 2008, Ruprecht vowed that Sotheby’s had learned its lesson. For the next few years, the company gave out few guarantees, and when it did, it hedged its risk by enlisting third parties (usually big collectors or dealers) to underwrite them in return for a cut of the proceeds. While this whittled away at Sotheby’s profit margin, it seemed a prudent course. But by 2011, the art market had rebounded to its prerecession peak, and the struggle began anew.

“It’s kind of a bizarre dynamic,” says one prominent collector who has dealt with both auction houses. “On the one hand, it’s a duopoly; that’s a good position for any business to be in. But from another angle, they fight like cats and dogs, and it’s not too far from being emotional. They often prod each other into doing stupid things.”

To Loeb and others, Ruprecht has complained that Christie’s is the one pushing the competition back onto a dangerous path. For the past 15 years, Sotheby’s rival has been owned by François Pinault, one of the richest men in France, who has treated it as an extension of his luxury-goods empire (Gucci, Balenciaga) and his renowned personal art collection. In 2010, Pinault hired Steven Murphy, an American with a background in music and magazines, to run the business. Since then, Christie’s has raised the stakes of its auctions while plowing untold millions into growth areas like China and private sales, where both houses are trying to win market share away from art dealers.

Christie’s total sales—including the private deals—surpassed $7 billion last year, nearly $1 billion more than Sotheby’s. No one knows how much Pinault has spent, but he is clearly sacrificing some profits to attain a dominant position. “They are being very strategic and long term,” says Michael Plummer, a former employee of both auction houses who now runs a financial-advisory firm, Artvest Partners. “Investing heavily now in an effort to relegate Sotheby’s to permanent second-class status.”

Despite a deep but brief dip around 2009, Sotheby’s auction-sales figures more than doubled over the past decade, and Ruprecht rejects the notion—put forth by Loeb, among others—that the company’s performance is lagging behind Christie’s. “As the leader of the only publicly traded global auction house,” Ruprecht told me, “I probably have some perspectives that will differ from those who view themselves as experts on our world.” He cites Sotheby’s strong stock price, growing presence in Asia, comparative strength in more mature art sectors like Impressionism, and successful private sales as evidence that the fixation on flashy contemporary auctions is misplaced. Sotheby’s claims—with some justification—that it is unfair to compare Christie’s results, which are reported only in promotional materials, with its own, which are publicly reported to shareholders who demand an annual profit. “That’s how we define success, not by being the biggest,” Ruprecht said. “We are accountable to the bottom line, not the headline.”

For more than a decade, Tobias Meyer was Sotheby’s field general in the consignment war. A slight man with a square jaw and a magnificent head of hair, he was an outsize figure and the keeper of some of the house’s most important relationships. Meyer and his husband, an art adviser, live on the 66th floor of the Time Warner Center, in the same environs as their clientele. They sometimes entertain collectors at an austere, wedgelike country house Daniel Libeskind designed for them in Connecticut. Some found Meyer arrogant, but he was an unquestionably canny judge of the tastes of the global elite. He is widely credited, for instance, with creating the market for Richter’s giant abstracts, which collectors esteem for their “wall power.”

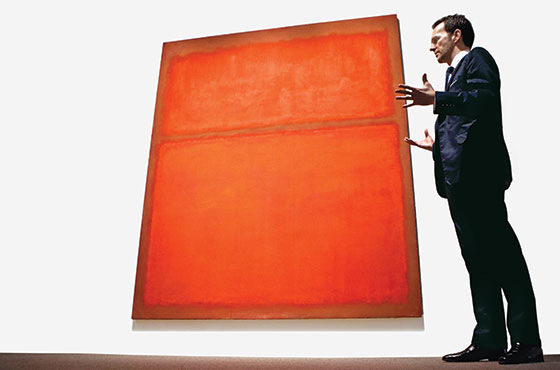

Meyer’s most valuable asset, though, was not the art—that came and went—but information: tightly guarded knowledge about who owned what masterpieces. “Anything below $20 million to $30 million,” says one art adviser, “was not of interest to Tobias.” If there was an artwork he wanted, he might spend years courting its owner. “You dream about objects, but you know you’ll never get to sell them,” Meyer said before November’s auction as he stood in front of the Warhol Silver Car Crash. “And then we get a call, and we say we have to fly somewhere and see a painting.”

In 2010, Meyer caught wind of just such a rare opportunity: David Martinez Guzman, a Mexican-born financier, was toying with selling a Rothko. Martinez is one of the handful of people who regularly buy and sell the kind of powerful works that can anchor an auction. Meyer knew Martinez as a Sotheby’s customer and a fellow resident of the Time Warner Center, where the collector owns a 12,000-square-foot penthouse. An intensely secretive man, Martinez made his fortune investing in distressed emerging-market debt. In art, as in business, he carries a reputation for wily instincts. In February, for instance, Martinez reportedly sold a Francis Bacon portrait at a Christie’s auction in London for $70 million, capitalizing on the momentum created by the recent record for the Bacon triptych—which Martinez is also widely presumed to have sold.

Typically, such transactions remain shrouded in murk and misdirection. But the details of the Rothko consignment were revealed in unusually stark terms by a federal lawsuit filed in Dallas. At a trial last year, Martinez testified that he considered Meyer a “personal adviser” and had consulted both him and his counterpart at Christie’s, Brett Gorvy, before he had purchased the Rothko in 2007, for $19 million, from a Dallas society figure named Marguerite Hoffman. “I love this painting; it’s very beautiful,” Martinez testified. “But we’re talking about very large amounts of money here.”

Officially, Martinez purchased the Rothko through a company incorporated in Belize. In the three subsequent years, he only looked at it once, at a Swiss warehouse where he keeps a substantial portion of his collection, which he estimated to be worth more than a billion dollars. “I like to compare collecting art to the same way that ancient cultures used to collect, for example, gold,” Martinez testified. “Some sort of store of value.”

Martinez constantly trades, though, and that was why Meyer was summoned to the Upper East Side gallery of L&M Arts one day in 2010. The collector wanted to compare his painting against another Rothko that was up for sale by L&M for $33 million. To assist his decision, the dealer had the paintings hung on facing walls of the gallery. Martinez’s Rothko was red—often said to be the most valuable color at auction—and big, roughly eight by six feet. But he preferred the other one, which was in darker hues of brown and green. Martinez asked Meyer whether the red Rothko would fetch a good price at auction. Meyer was ecstatic. He estimated that even on a bad day, it would make $18 million, but a likelier price would be $25 million, maybe even $30 million.

Martinez, a tough negotiator, was looking for concessions. He wanted the entire seller’s commission waived, which was no problem for Meyer—consignors of works above the million-dollar mark almost never pay such fees anymore. But Martinez also demanded a piece of the buyer’s premium, the extra fee on top of the hammer price. Once, the premium was considered untouchable, but in recent years, major consignors have been successfully demanding what auction-house employees call an “enhanced hammer”—or, in unguarded moments, a kickback. The two sides signed a contract that gave Martinez a large percentage of the premium if the Rothko sold for less than $25 million.

In addition, Martinez wanted a loaned advance of $15 million, which he would apply toward buying his new Rothko. Sotheby’s financial-services department is one of the lesser-known facets of its business; since few banks will take art as collateral, it is a crucial lending source for private dealers and collectors. Art loans are tricky, though, because they depend on the valuations of Sotheby’s specialists, who are trying to induce consignors. The Martinez loan was much larger, as a percentage of the estimated price, than Sotheby’s internal guidelines call for, but Meyer pressed for a quick approval.

“I do not want him to change his mind and not sell it in the end,” Meyer wrote in an email to finance-department executives. “He is mercurial.”

In the end, Meyer got his painting, which became a centerpiece of a Sotheby’s sale in May 2010, and it sold for $31.4 million. The only unhappy participant was Hoffman, the previous owner, who claimed to have sold the painting under a binding confidentiality agreement, assuming the painting would disappear into a private collection, not end up being flipped at a highly publicized auction. Her claims against Meyer were dismissed, but a jury last December found Martinez and L&M Arts (which was aware of the confidentiality agreement) liable for damages of $1.2 million.

It’s safe to say that the machinations surrounding Martinez’s deal with Sotheby’s for the red Rothko are unusual only in that they were exposed to scrutiny. Before Christie’s huge sale in November, the auctioneer read a legal disclaimer so long and confusing that the hall broke into laughter. The disclosures included guarantees that were financed by third parties who might also be bidding—an obvious conflict of interest, since the guarantors would have an incentive to drive up the price. Christie’s also disclosed an unexplained “financial interest” in many lots, including the Bacon triptych. Multiple sources said at least one piece, a Christopher Wool that sold for $25 million, came from Pinault’s own collection (though Christie’s denies this). Koons’s orange Balloon Dog—the marketable sculpture that Christie’s touted on tote bags—was consigned by the super-collector Peter Brant. After it sold for $58 million, the highest price ever for a living artist (to Jose Mugrabi, another super-collector), Brant revealed to the Times that because the dog had failed to hit an even higher target, Christie’s had given him the entire buyer’s premium. Once marketing, shipping, and other costs are figured in, Christie’s almost certainly lost a fortune on the consignment.

“That’s not abnormal,” collector Michael Shvo says of the Brant deal. “It is something that is done on a daily basis with both auction houses.”

The Balloon Dog may simply have been a loss leader, and Christie’s claims the November sale was profitable overall. But many market participants say Christie’s has been the more aggressive party in the price war. “Brett’s job is to mortally wound Sotheby’s by assembling the best auctions for Christie’s,” Levin says. Sotheby’s says its star lot last fall, the Car Crash, was one of its three most profitable sales of the year. But overall, it has responded by spending more on marketing even as it gives deals to consignors. As a result, its public filings reveal an erosion of profit margins. In 2010, Sotheby’s total sales of $4.8 billion yielded a relatively meager $160 million profit. Last year, total sales were $6.3 billion, but its profit was almost 20 percent lower.

Some argue that in order to compete, Sotheby’s needs its own Pinault: someone with a taste for beauty, little need for quarterly profits, and a desire to be the master of a slippery game. David Schick, a research analyst with the firm Stifel Nicolaus, has argued that the company is an ideal candidate for a leveraged buyout. “It’s a perfect trophy asset,” he says. “Like the Yankees or Manchester United.” But the company’s current stock-market value, $3.2 billion, is probably too expensive for a plaything, and takeovers aren’t Loeb’s style, anyway. He’s not a buyer; he’s a trader.

As pressure mounts, both auction houses have become more aggressive in scavenging for inventory. London dealer Kenny Schachter recently wrote a column for Gallerist about the lengths Sotheby’s went to in trying to secure access to a deceased in-law’s collection, which included offering a bounty to a family friend. Afterward, the dealer heard from Loeb. “He said to me that it was an epic tale of insensitivity,” Schachter told me. “I said, ‘The wolves are huffing and puffing.’ And he said, ‘We’re not trying to blow the house down; we’re trying to resurrect it, to build a better business.’ ”

I heard of many similar conversations—Loeb is clearly doing his own research on Sotheby’s. He has expressed an outsider’s skepticism of the blood sport between the houses, wondering why they can’t hold the line against consignors when it comes to commissions. Instead of using discounts to secure inventory, Loeb argues, Sotheby’s should think more like savvy collectors do. He often says that Sotheby’s should be more like an “art merchant bank,” a boutique institution that combines advisory and financing functions. He wants the company to engage in more direct investment, to “judiciously take principal positions” in the artworks it sells. He has also backed a proposal by another activist shareholder, Marcato Capital Management, that calls for Sotheby’s to use bank financing to expand its art lending. Marcato suggests that the company bundle and securitize its loan portfolio, citing a model developed for Marriott time-shares.

Sotheby’s has already been moving in this direction. In January, in response to Marcato’s proposal, it announced a plan to expand its financial services through a new $450 million credit line. This should allow the company to develop its role as one of the primary money markets for major dealers and collectors. (Peter Brant has made use of Sotheby’s loans, as has Jeff Koons, who borrowed against his own work.)

Loeb told Sotheby’s management that he approved of the financial-services expansion as well as a decision to again consider selling the York Avenue building and other property in London, cash-generating plans that have allowed the company to promise a special $300 million dividend to shareholders. This wasn’t enough to stop him from launching his public campaign, though. Sotheby’s has adopted a “poison pill” takeover defense, preventing Loeb from amassing more than the roughly 10 percent of shares he currently holds, but last week Marcato, which owns 6.6 percent of the company, announced it would be supporting Loeb’s nominations. Sotheby’s stock has remained fairly flat since the activists disclosed their positions over the summer, so they have every incentive to make some noise.

Such board fights often end up turning nasty. Loeb’s October letter described, for instance, an embarrassing six-figure corporate tab at Blue Hill, and Sotheby’s culture could supply him with plenty of additional material. Much of the management team around Ruprecht has been in place since the era of Taubman, whose son still serves on the board. (Recently, the London office held a 90th-birthday party for the disgraced tycoon, though Sotheby’s says the family paid for it.) The financial-services department not only serves the cozy art marketplace but also has been used in the past by top executives. Sotheby’s issued Ruprecht an $850,000 loan to buy his home in Greenwich before he became CEO. State records show that on two occasions, around the time Meyer purchased his $5.5 million condo in 2004 and built his country house in 2009, Sotheby’s issued him loans against artworks by Warhol, Barney, and Meyer’s friend John Currin. (A Sotheby’s spokesman says any loans to employees are subject to “the same rigorous due diligence and underwriting standards” as those to other clients.)

Meyer’s overnight disappearance offers another potential area of intrigue. The timing of his resignation led some to conclude that he and his salary were offered up as a sacrifice to Sotheby’s angry shareholders. Though his compensation was never disclosed, it is believed to have been enormous. “They certainly did invest very heavily in keeping him, and keeping him happy,” says David Nash. But Loeb has denied that Meyer was meant to be the target of his pressure. Though no great administrator, Meyer was an ambitious dealmaker in a company that Loeb says should be making bigger deals, and Loeb has told some that he views the departure as a sign Sotheby’s isn’t capable of retaining top talent.

A source familiar with Meyer’s thinking says he had become frustrated with the public company’s bureaucracy and was attempting to negotiate a more influential place in the hierarchy, something like a creative-director role. But Ruprecht wasn’t interested in giving Meyer the power he wanted. Since leaving, Meyer is said to have expressed a desire to become “invisible,” and he recently put his Manhattan condo on the market, for $17 million. His mental map of the world’s art treasures should serve him well as a private dealer. There are, however, those who think that if Loeb were calling the shots at Sotheby’s, Meyer might return in some sort of rainmaking role.

The next big sales are in May, around the time of the annual shareholder vote. If Sotheby’s once again trails Christie’s by a large margin, says Anders Petterson of the market-research firm ArtTactic, “you are tipping that balance, and the buyers suddenly may exit out Sotheby’s door.” Given the grave danger in looking second-rate in a marketplace built almost entirely on perceptions, Ruprecht and his staff have been forced to take some bigger risks. Sotheby’s offered more than $200 million worth of guarantees prior to last November’s auctions, only a quarter of which were offset by third parties. (A big one went to Steve Cohen, who, in the midst of his insider-trading travails, consigned several works with mixed results.) The company’s latest filings suggest it is moving in a similar direction for its May sales. This is a course Loeb has advocated, so long as it is done intelligently, but it’s a high-stakes game. Even a single bad bet can have a meaningful impact. Last year, Sotheby’s ended up owning a $70 million diamond after a winning bidder failed to make payment—the largest failed guarantee in recent memory.

The market for diamonds is probably more stable than the market for Kippenbergers, but the incident gives credence to the suggestion, made by many in the art world, that in its desperation to prove itself to shareholders Sotheby’s is courting a familiar disaster. It’s generally estimated that there are maybe 100 serious players in today’s art market: The buyers, sellers, debtors, and guarantors are the same people, exposed to the same risks. “The practical reality,” says Michael Plummer, “is that most everyone in finance, even the collectors themselves, distrusts the economic rationality of the art market.” Guarantees are, in effect, bets on the value of art, made at the moment the auction house has the least leverage, because it is in a breakneck race with its competitor. Loeb may cash in his Sotheby’s stock before the downturn comes—but it always arrives, often all at once. The collectors stop buying, and the houses end up with lots of overpriced pictures and red ink. That’s the downside to Sotheby’s position between the billionaires: It’s always the middleman who ends up getting squeezed.