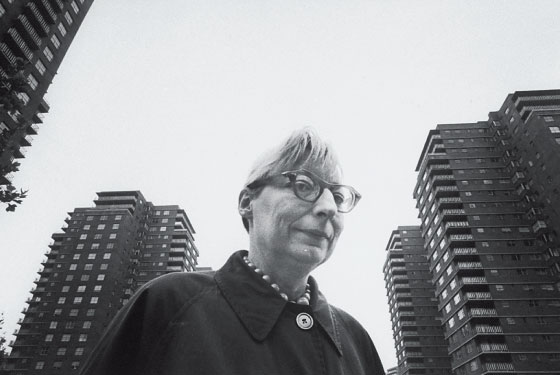

Jane Jacobs, the mousy, white-haired street fighter of Greenwich Village in the sixties, is famous for the wrong things: battling the overweening policies of urban renewal and defeating Robert Moses’s proposal for a highway across lower Manhattan. Jacobs showed that ordinary people could don activist armor and win, a feat that has led to a distortion of her legacy. Today, for every grassroots group trying to keep polluters clean, housing affordable, and bureaucrats honest, there is another, equally loud agglomeration of neighbors demanding that gentrification stop as soon as they move into the area.

Forty years ago, the conflicts that shaped the city fell into a stark but deceptive narrative: Moses, the pharaoh of tolls and parks, against Jacobs, wielder of the lucid pen; megaplans and highways versus sidewalks and stoops. It was not really so simple then, and it’s gotten much more tangled. Earlier this year, the Museum of the City of New York tried to rescue Moses from caricature with an exhibit that sprawled across three venues. Now, a year and a half after her death, it’s Jacobs’s turn to come in for a bit of nuance, though in an aptly smaller-scale way. “Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York,” at the Municipal Arts Society, nudges viewers into looking around their neighborhoods with Jacobs-ean alertness to detail.

What resonates most today is her role as an observer of urban liveliness. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, as well as in the shelf’s worth of other books she wrote over a long life, she analyzed the mechanisms that give any few blocks on Broadway their exhilarating, mixed-up energy, rather than the windy bleakness of, say, Detroit, or the stately quiet of Park Avenue at midnight.

Naturally, those who lack her perceptiveness have enthusiastically perverted her major points. As with many prophets (Muhammad, Marx, Lennon), Jacobs’s name has been attached to projects and causes that would likely make her cringe. She pointed out that a neighborhood feels most like a neighborhood when it has a mix of uses that keep it busy all day and into the night. So developers of those megalithic complexes combining theaters, hotels, apartments, offices, and malls claim that Jacobs would’ve liked them because they are thronged around the clock. She appreciated a combination of new and slightly dilapidated buildings, so that boutiques consort with bodegas; preservationists therefore attempt to freeze various neighborhoods in time. She spoke lovingly of the “ballet of the good city sidewalk”—and out in the city’s fringes, New Urbanist planners build pedestrian-friendly enclaves for the affluent and assert that they resemble her kind of town. Jacobs saw that cities are complex, and her arguments were, too; boil them down and they lose their texture.

She also understood that urban systems are perpetually in motion. Today’s Village bears little resemblance to her disheveled neighborhood of corner cranks, antiquarian bookstores, jazz clubs, hardware stores, and unhygienic cafés. Jacobs coined a term far more eloquent than “gentrification” for the inexorable process by which charm attracts money, which then leaches out the charm. She called it “oversuccess,” which could apply equally well to her and to Robert Moses. Both failed at times, but mostly they were oversuccessful.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.