Among political strategists, it’s an article of faith that the most optimistic candidate wins the election. This assumption isn’t based on focus-group hoodoo, but the work of the renowned psychologist Martin Seligman and his then-colleague Harold Zullow, who in 1990 systematically analyzed 84 years’ worth of acceptance speeches of the major presidential candidates for their party’s nominations. In 18 out of 22 instances, the man with the cheerier message carried the day.

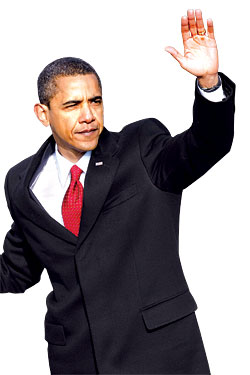

In light of this finding, Barack Obama’s inaugural address stood out as a startling bit of counterprogramming. Not only did he give voice to our flagging national morale (“a nagging fear that America’s decline is inevitable”), he dared point out that some of this mess is of our own unlovely making (“our collective failure to make hard choices and prepare the nation for a new age”).

Many in the punditocracy pronounced this speech a downer, and possibly even contraindicated: Why on Earth would the public want to hear such things in an hour of need? But Seligman himself, a lion in the field of positive psychology, has said that his data was more complicated than his published results suggested. “We did something we didn’t publish,” he told me in a 2006 interview. “We analyzed the content of every inaugural address, and we compared it with historians’ ratings of greatness.” What they found was that optimism and greatness had virtually no correlation. What predicted a great president, rather, was a certain ruminative quality in his inaugural address, combined with action-oriented rhetoric. (A line like “The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works” seems very promising in this regard.) Perhaps more important, they found a high correlation between a president’s intellect and … pessimism, “Lincoln being the primary example,” Seligman said.

Listening to the inauguration last week, Joshua Wolf Shenk, author of Lincoln’s Melancholy, says he did indeed hear echoes of our sixteenth president. “Abraham Lincoln was constantly telling his audience the ways they needed to be better and work harder and admit that the reality was more complicated than their prejudices would instinctually have them believe,” he says. The best example, he adds, was Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. “He was arguing that both sides thought God was on their side,” he notes. “But that one side had to be wrong, and that both sides might be wrong.”

Optimism is a lovely quality. But it does not, perforce, lead to sound policy-making. In 1979, two researchers named Lyn Abramson and Lauren Alloy conducted an elegant experiment, now famous in the annals of psychology, showing that depressives sometimes make better realists. The design of their study was simple: Participants were asked to turn on a green light by hitting a button. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it didn’t—the light was programmed to switch on at random intervals. What was intriguing was that the depressive participants almost always knew when they had no control. But 35 percent of the time, the nondepressed participants believed they were turning the light on and off, when in fact their exertions had no effect at all.

As George W. Bush’s presidency wore on, it became painfully clear that he was the type of fellow who mistakenly believed he was turning on that green light. Sunny until the very end—“the way he always is,” as his press secretary said on the day of his departure—Bush seemed eerily positive about his most ill-fated endeavors, no matter how many sirens were whooping in the background.

It seems that there’s a threshold for how much the public will endure of this delusional optimism. (Witness the New York Times survey from last week showing that most Americans believe we need two years to solve our problems.) No one is saying that Obama is a depressive or a pessimist. He ran an inspirational campaign, notes of which still rang out in his inaugural address. But he is a realist. Unlike his predecessor, he can live with two ideas in tension, accepting the brutality of a situation while striving for a world without it. That’s nondelusional optimism—or, in Obama’s vernacular, hope.

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].