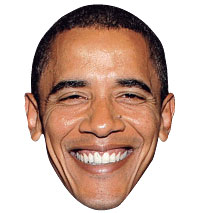

Of all the moments of oratorical loveliness in President Obama’s address to the joint session of Congress last week, the one that had the most inspirational power—to me, anyway—was an unscripted one. On C-Span, it happened at minute 36, second 56, just after the president told his former colleagues that they shouldn’t pass along the national debt to our children, which earned him a standing ovation and raucous cheers from both sides of the aisle. “See?” he said, a big accordion-grin spreading across his face as he looked happily over the crowd. “I know we can get some consensus in here.” And for the next few seconds, it looked like Barack Obama, the man who’s fought repeated accusations that he’s too dour in this time of national need, was choking back a laugh.

Erving Goffman, the famous mid-century sociologist, would have said that what the audience magically witnessed at that moment was Obama’s backstage persona, rather than his front-stage one. He pulled the mask off, let us see a glimmer of the guy who’s spent the first month of his presidency walking headlong into the wind, facing down not just awful economic troubles but a squall of Republican opposition to his plans to solve them. In his seminal 1959 text, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman points out that when publicly esteemed people perform, they often subtly disbelieve their own words. The reason isn’t malice or self-delusion, he implies, but self-protection: “They can use this cynicism as a means of insulating their inner selves from contact with the audience.” He gives the example of medical students, who may enter their profession with lofty ideals and soft hearts but learn to talk to patients with game faces on.

The problem is, we don’t like it when doctors wear their game faces as they deliver cancer diagnoses, and we don’t like politicians who wear their game faces as they deliver horrible news about the economy. What we want right now is to be identified with, not condescended to. And that’s why those who’ve strayed from the political script—as Obama did, frankly acknowledging that getting Washington to function in periods of crisis is difficult—have been the winners in recent months, and those who’ve stuck with the script have been losers. Timothy Geithner’s speech, too veiled and cautious by half, seemed cynical; so too did Bobby Jindal’s smiling robo-response to Obama’s address. It’s why David Brooks, ordinarily a man of judicious mien, got so much positive attention for his unbound response to Jindal’s anti-government pabulum—“I think it’s insane,” he told Jim Lehrer—and why Chris Matthews, who uttered “Oh, God” into a hot mike as Jindal entered the room, barely suffered for his undisguised moment of disgust. This wasn’t a moment for “stagecraft,” as Matthews said later, explaining his exclamation. It was a moment for candor. In a crisis like this, leadership involves tossing aside the usual mask. “I get it,” said Obama at another point in his speech. And he did.

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].