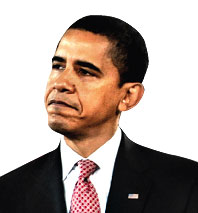

In last week’s press conference, President Obama committed what’s often thought to be the cardinal sin in politics: He neglected his base. He called on the Washington Times, not the Washington Post; Stars and Stripes, not the New York Times; Fox, not MSNBC. The message was that, in the midst of the political cacophony, Obama was going to talk to everyone.

This month, it so happens that Cass R. Sunstein, the Harvard law professor and Obama’s recently appointed regulatory czar, has a book coming out that sheds light on the virtues of open-mindedness. In Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide, Sunstein argues that spending too much time in the company of like-minded people serves only to exaggerate your own views and make you less tolerant of differing opinions. This tendency, he says, explains many things, from the angry tenor of the blogosphere to the extravagant sums awarded by juries. In the book’s most memorable and elegant experiment, he and his colleagues went to Colorado and drew a total of 60 people from two locations: Boulder, a liberal enclave, and Colorado Springs, a conservative one. All participants were screened to conform to stereotype. (“For example,” he writes, “group members were asked to report on their assessment of Vice-President Dick Cheney. In Boulder, those who liked him were cordially excused from the experiment. In Colorado Springs, those who disliked him were similarly excused.”) All were then asked to write down their points of view about three subjects: gay civil unions, affirmative action, and an international treaty on climate change. They were broken into ten groups of six, five of them left-leaning and five of them right, and told to debate these topics for fifteen minutes. Then their points of view were rerecorded. And in almost every group, members ended up more militant than when they started.

From this perspective, the excesses of Obama’s predecessor make chilling sense. George W. Bush famously lived in a bubble, and Sunstein’s point is that bubbles don’t just insulate; they radicalize. From this comes the uttering of such sentences as “We create our own reality.”

Obama seems to live by the opposite creed. In the summer of 2006, as I was following him on a loop through downstate Illinois, I asked Obama whether he read Daily Kos and other liberal blogs. “One good test as to whether folks are doing interesting work is, ‘Can they surprise me?’ ” he replied. “And increasingly, when I read Daily Kos, it doesn’t surprise me.” Two and a half years later, Obama’s first media overtures were toward those who did surprise him: conservative columnists. He then went on to make a series of moderate appointments, including Paul Volcker, the former chairman of the Federal Reserve under both Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, and Timothy Geithner, a consummate creature of Wall Street.

Geithner’s appointment has gotten Obama into a fair amount of trouble on the left, as has his continued engagement of Wall Street. One could say he’s kowtowing to scoundrels. Maybe he is. But one could also say he’s trying to hear them out—and not to alienate the people who might be best equipped to undo this mess.

Toward the end of Annie Hall, Woody Allen spies a copy of National Review in Annie’s apartment and demands to know what it’s doing there. “Well, I like to get all points of view,” she protests. Lately, I’ve thought a lot about that scene. Remember, Annie came from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where others probably read National Review, too. In 2008, Obama managed to win Chippewa County. In 2004, it went to Bush.

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].