When I last glimpsed the famous large ears of Rodger McFarlane, who chose Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, as the enigmatic site for his recent suicide, he was standing outside a May 1 screening of Outrage, a documentary about closeted politicians. Rodger was the film’s standout star, the only one with laugh lines. (“I actually kind of admire them,” he says of the stalwart wives of Larry Craig and Jim McGreevey. “But that is some weird shit.”)

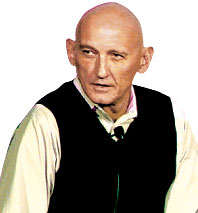

Rodger was always the star. He liked to say “I won my Oscar at a young age,” in reference to his work running Gay Men’s Health Crisis, which is where we met 25 years ago. He went on to become one of the savviest organizational strategists in the fight against AIDS. Six foot six and athletic, with towering Alabama charm and wit, he built Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS into a grant-making behemoth, and then moved to Denver to remake Tim Gill’s gay-rights fund, where he worked until December, into a player in national politics. Now 54, you could still imagine him aboard a Navy submarine or trekking to the North Pole or competing in extreme Eco-Challenge races.

He looked happy to be back in New York. He did not seem to be in pain. But it turns out that he’d broken his back on the first day of an Eco-Challenge in Fiji in 2002, and though he underwent one operation, his friend Howard Grossman, a doctor, tells me he refused the surgical rebuilding that might have lessened his agony. His athletic life was behind him. “I know that was very distressing for him,” says Tim Sweeney, his successor at the Gill Foundation. “I would say, ‘Go coach! Do amateur competitions,’ and he gave me this look like ‘Are you out of your mind?’ ”

What none of his friends knew was that a recent heart attack added to his troubles. He refused bypass, too. He hated the idea of being hospitalized. Though he’d written The Complete Bedside Companion: A No-Nonsense Guide to Caring for the Seriously Ill, he was a terrible patient.

In his world, he was the caretaker. He doted on his brother David, who died of AIDS, and on the literary agent Jed Mattes, as he died of cancer, and on his old flame Larry Kramer, during a liver transplant. “Rodger stage-managed everything,” Kramer says. “He was in his element there.”

“Let’s catch a drink,” Rodger called to me after the screening, but two days later, he was already in New Mexico. The trip had been too much for him. “I really didn’t want to come back to civilization at all,” he said.

He had checked in to the Blackstone Hotsprings motel, and mailed farewells to his closest friends. He made arrangements with an undertaker. He settled his bills, and on May 15, sometime after 9 a.m., a bike rider found his lanky remains, pistol in hand. “I think of a gun as my Samurai sword,” he wrote.

Rodger always deplored self-pity. Grossman believes Rodger’s fatalism probably can’t be separated from his history in the epidemic, watching so many people die so horribly. “Life is fucking tough, and it’s not fair, goddamn it,” Rodger told me a year ago. “And if you didn’t learn that in the eighties, you didn’t learn anything.”