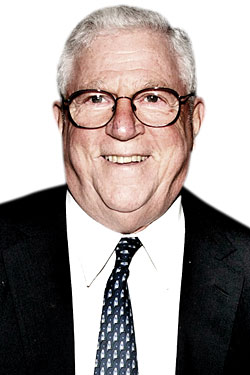

On a recent Friday morning, the only thing cheery about Lieutenant Governor Richard Ravitch was his tie, decorated with tiny Christmas trees and Santas sneaking behind them. He’s feeling sick. Nothing too serious—a cold, maybe the flu—but the bug has sapped his characteristic swagger and muffled his baritone. On the desk of his midtown corner office, a tea bag lies fallow on a message slip, near a packet of Tylenol. His staff is urging him to call it a day, but he’s got a meeting with the governor. “I’m a little tired,” he says, “but I expect to get some rest over the holidays.”

It’s been a grueling, and even humbling, period for Ravitch, the most important unelected government figure in New York. Governor Paterson has entrusted him with mapping out a long-term solution that no one in Albany wants to solve: how to dig New York out of the rubble of decades of fiscal management and debt. Lawmakers are scoffing at Paterson’s ambition for a multiyear budget. (Says a senior Senate aide: “The notion that we deal in four-year plans is bullshit because nobody knows who’s going to be running things a year from now.”) Labor, health care, and cultural groups have tuned out Ravitch’s warnings, clamoring for more as usual.

Ravitch hasn’t been in government for the past 27 years. He’s Rip Van Winkle, come to find a changed and rather disturbing world. More than a generation ago, when he first stepped onto the political stage during Governor Hugh Carey’s administration to salvage the Urban Development Corporation from financial ruin, the governorship was more powerful and the city’s civic elite wielded more influence.

In the ways of modern Albany, Ravitch was something of a naïf. During the heat of negotiations over the deficit reduction this fall, Paterson was meeting with a senior aide when Ravitch barged in. The lieutenant governor had just met with a lawmaker who told him something he couldn’t believe. “He saw this as a special news bulletin, like an emergency,” Paterson recalled. “He told me a particular legislator didn’t care what happened to the deficit-reduction plan. I looked up at him, and we’re like, ‘What else is new? Welcome to Albany.’ ”

Ravitch’s arrival coincides with the best era in Paterson’s tenure since, essentially, his first day. (Harold Ickes, the governor’s new consultant, probably has a great deal to do with this.) The governor’s poll numbers are crawling out of the basement. His message is less erratic. Paterson’s protests against legislative paralysis and unilateral measures to avert insolvency have started to mend his hapless reputation. Behind the most important policy decisions of late—such as the governor’s move to impound $750 million in school and local aid—has been Ravitch’s guiding hand.

Given the plummeting revenue forecasts—a four-year deficit projection of $44 billion—Ravitch assumed he’d be making more inroads by now. “I’m frustrated because people’s behavior hasn’t changed,” he said. “The unions still think that by throwing pickets and taking ads out they can prevent the Legislature from making cuts. The banks still have people going to Albany with all kinds of cockamamy borrowing schemes, which are the things that got us in trouble in the first place. The press is more interested in writing about ethical transgressions than complicated budget stuff.”

Still, he is not as cynical as many of the people who’ve spent more time in Albany lately—and that might be his biggest advantage. “I didn’t even realize what an asset a lieutenant governor could be,” Paterson told New York. “The thing he told me was not to be afraid to take extraordinary action. He reminds me of what reality is. Some of us had to deal with this so long that we think this process is reality. But it’s a bunch of people who will not manage other people’s money as well as they would manage their own.”

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].