The past three years in New York politics has been a period only a prosecutor could love. The range of sins is bi-partisan and impressive, in a twisted way, from the vehicular (Alan Hevesi, Joe Bruno, Vito Fossella) to the carnal (Eliot Spitzer, Fossella again) to the violent (Hiram Monserrate) to the good old-fashioned larcenous (Bernie Kerik, Miguel Martinez, among too many others). David Paterson’s mistakes cross numerous categories.

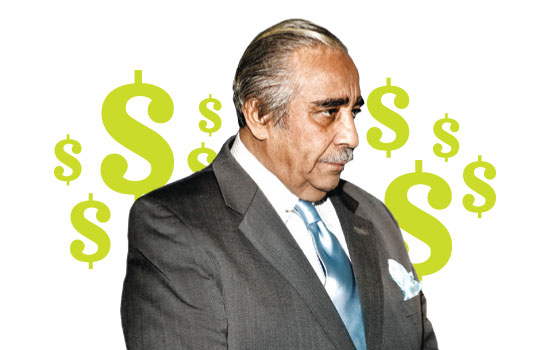

The bad acts of each man had consequences for his constituents. Yet even allowing for the alleged multimillion-dollar public-pension-related thievery of Hevesi political strategist Hank Morris, last Wednesday’s decision by Charlie Rangel to quit—begrudgingly and, he insists, temporarily—as the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee will likely be the most expensive day in New York political history. Rangel’s appetite for Caribbean junkets and cheap apartments will cost us hundreds of millions of dollars.

It would be nice if Congress allocated money on the basis of need and merit. If that was ever the way the game was played, it sure isn’t now, and wouldn’t be even if tea partyers were to win all 435 seats. The Ways and Means writes tax laws and has jurisdiction over billions of dollars in pocketbook issues, including Social Security, so its chairmanship is a position of enormous power. The job’s significance is magnified right now, during the health-care debate, and it’s especially important for New York because of the implications for Medicaid funding and taxes on Wall Street bonuses. That Rangel’s ability to shape crucial legislation has been demolished, and the state’s 40-year investment in his career scuttled, by his laziness in filing financial-disclosure paperwork is borderline tragic.

Those missteps, while sloppy and arrogant, would have been survivable if Rangel’s timing weren’t so bad. But the roughly 40 congressional Democrats who are vulnerable this fall—like Staten Island’s Mike McMahon—didn’t want to go back to their districts and defend Rangel and Nancy Pelosi against Republicans braying (hypocritically, of course) about corruption.

Rangel’s decline will also roil the internal dynamic of the state’s delegation. “There will be a power vacuum,” a New York House staffer says. Instead of first going to Rangel, legislators might deal directly with Carolyn Maloney or Jerry Nadler; Joe Crowley, the throwback Queens pol, improves his position in the House leadership pipeline; Anthony Weiner may finally come out of his shell. Those new openings are only partly welcome, because the entire delegation benefited from Rangel’s stature. That clout is lost now, and it isn’t likely to return anytime soon: New York went from 1955 until 2007 without one of its own as chairman of Ways and Means. Rangel did plenty of good things along the way—funneling empowerment-zone money to Harlem, staunchly opposing the Iraq War—but his four-decade quest for serious power ended last week. Making the timing even worse: New York’s delegation is expected to lose a seat in next year’s reappointment.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.