Before last week, no one believed that Barack Obama had enough LBJ in him to pass his health-care bill. A couple months ago, in fact, when passage seemed like a distant dream, an old, possibly apocryphal LBJ story went around Capitol Hill—mainly as a wistful point of contrast, a way of asking aloud why Obama couldn’t trade his velvet oratory for a wooden club. In it, Democratic Idaho senator Frank Church was confronted by Johnson for his increasingly vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. Church explained he’d come around to the view of Walter Lippmann, the newspaper columnist. “Frank,” said LBJ, “the next time you want a dam in Idaho, just go to Walter Lippmann for it.”

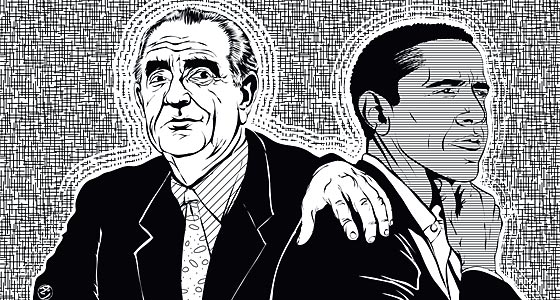

Obama, however, was considered too aloof to flatter or bully; one look at the iconic photographs of Johnson, looming like a golem over his targets, told you all you needed to know about the intensity this president lacked. Yet during the final week of the health-care debate, Obama phoned or met with 92 congressmen, suggesting he wasn’t quite so remote. The difference was how he did it.

“There was no bartering, no threats,” says Congressman Brian Baird, a thoughtful psychologist from Washington State who, like many moderate Democrats, had reservations about the cost and complexity of the legislation. “It was: Let me start by laying out my position, and then I want to hear yours.” From there, the two men talked for twenty or so minutes in the Oval Office, purely about the substance of the legislation—a marked contrast, Baird notes, from the emotional entreaties he got from both supporters and haters of the bill. “Yet here was the president, who has more at stake than anyone, and he wants to discuss policy.” The president never pressed Baird for a commitment during the discussion, but he voted yes in the end.

“Obama had an approach unlike anything I’ve ever seen any other president use,” says Dennis Kucinich, the progressive Ohio congressman and former presidential candidate who swore he’d never vote for any bill without a public option. “Honestly, if I were to try to characterize it, I’d say it was a dialogue along the lines of Martin Buber’s I and Thou.” Which means? “He goes very deep into looking at an issue from the side of the person to whom he’s speaking.”

On the face of it, this observation may seem like the sort of kooky mysticism that Kucinich made famous on the campaign trail. But his point is that people can either talk at you or to you. Most politicians are monologuists. Obama isn’t. Kucinich and Obama had many conversations, including a long one in the Roosevelt Room on March 4. Eight other members were there, all prepared to vote yes, all facing Obama across a table, while Kucinich was off to the side. “There was a moment where—I don’t know what happened, really—but he tapped into a deep sense of compassion that I had for him,” says Kucinich. “It was this feeling of, you know, he’s putting everything he has on the line here.” He went home to his wife that night and said he felt bad he couldn’t help the president, who’d implied he didn’t know if he could win the vote. (Kucinich could identify with his need to tilt at windmills.) Later, on March 15, he accompanied Obama aboard Air Force One for the president’s last-ditch health-care speech in his district in Ohio. And in the end, he voted with him.

Like LBJ, Obama laid it on the line and appealed to the better angels of those who wavered. Yes, he cut deals, like agreeing to sign an executive order affirming the Hyde Amendment. But there were no reports of intimidation or threats of retribution. As it turns out, what makes Obama such an unusual politician in public is exactly what makes him so unusual in private: He’s passionate without heat.

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].