New York book publishing loves a tragic hero, especially when it sees one in the mirror. Historically a bastion of English majors and dissipated heirs, it savors the role of cutthroat capitalism’s noble victim. When the spare-parts conglomerates began snapping up book imprints in the sixties, their gentleman owners grumbled—and eventually sold out. When chain bookstores began shutting out the independents, publishers eulogized the mom-and-pops—even as they knuckled under to Barnes & Noble. When Google began digitizing their books, they sued—then settled. Going all the way back to the Depression, when they let stores return unsold volumes at no cost, publishers have met industry challenges with valiant defeat.

So it seemed again when the Justice Department brought antitrust charges against five big publishing houses two weeks ago, leading three to settle immediately and clear the way for Amazon to resume the price-slashing the publishers had been seeking to blunt. But then the familiar narrative took a turn. Two of the defendants, Macmillan and Penguin, stood their ground, saying they did nothing wrong in cutting deals with Apple (a co-defendant) that effectively raised e-book prices across the board. After decades of publishers making wan arguments appealing to nostalgia for the smell of rotting paper or the pure-heartedness of ye olde shoppe owner, the effect has been weirdly stirring. It may be, as the government’s lawsuit paints it, that these houses were pursuing a collusion “scheme” hatched “in private dining rooms of upscale Manhattan restaurants.” But even if a judge eventually rules against them, it’s heartening to see publishers—the people who actually know how to curate, edit, design, and care for books in ways Amazon just doesn’t or won’t—counterattacking for a change.

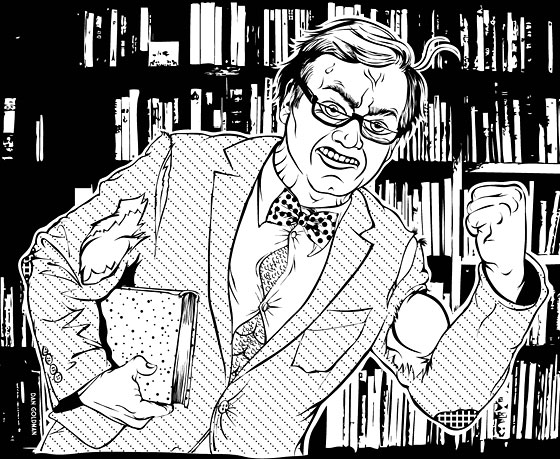

The two CEOs who haven’t settled the DOJ suit, Penguin’s John Makinson and Macmillan’s John Sargent, have cast themselves, not unconvincingly, as the last bulwark against Amazon’s total domination of the business. Sargent in particular has proved to be a new kind of publishing boss, not just a number cruncher or an aesthete but a fighter schooled in brinkmanship and muscle-flexing. Descended from publishing royalty (the Doubledays) but raised in swaggering Wyoming, he has the insider’s long memory and the outsider’s brass knuckles. Macmillan is the smallest of the big-six publishers, but that hasn’t dissuaded him from taking on Jeff Bezos, insisting in 2010 that Amazon let Macmillan have a say in what customers pay for its e-books. The online retailer retaliated by removing Macmillan digital editions from its virtual store. Sargent dug in; Amazon, amazingly, blinked. “We will have to capitulate,” Amazon stated, “and accept Macmillan’s terms because Macmillan has a monopoly over their own titles.” For once, a distributor had been forced to resort to the phony umbrage that had too often been the refuge of publishers squeezed by larger, more aggressive forces.

In the current case, the government uses that signal moment as further evidence of collusion, quoting e-mails sent in solidarity. Wrote one fellow publisher to Sargent: “I can ensure you that you are not going to find your company alone,” later vowing that “others will enter the battlefield!” Three of those combatants may have since slunk back to their redoubts, and for the two holdouts, victory is by no means assured. But at least the people who understand how to craft books have shown that they can also learn how to fight rough.

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].