Is New York in the midst of a new real-estate bubble? It can appear that way. In early March, my friend Ellen asked me to come with her to see a co-op she was hoping to buy. She’d already lost one bidding war, and she wanted moral support as she faced the possibility of a second. We met the broker at a two-bedroom in the West 100s. It was a nice enough New York apartment, two bedrooms on a wing off the living room and dining nook, and large windows framing big-sky views. Still, the kitchen needed a redo, the walls a once-over. The asking price was $1.2 million, the kind of number buyers used to go past 100th Street to avoid. Ellen and her husband offered $25,000 over the asking and pledged to cover the difference if the apartment didn’t appraise for the sale price. And still Ellen fretted she wouldn’t get it, despite her stellar credit, a secure job in finance, and an eager buyer for her current place, which isn’t even listed yet. Ellen turned out to be right; they lost to bidders willing to pay more than $150,000 over the asking price.

Certain cities across the country—Phoenix, Las Vegas, Miami—are just beginning to dig out from the collapse of the real-estate bubble in 2007. But New York appears to be fully reinflated and getting bigger. The city’s real-estate map has been completely redrawn, with neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant now attracting deep-pocketed buyers. In late March in Windsor Terrace, more than 60 house-hunters converged on a showing of a sweet little house—two stories, nothing grand—priced at nearly $1.5 million. Within days, six buyers had put in offers. A week earlier in Park Slope, 90 people converged on a duplex asking over $1.5 million, double what it sold for in 2011. And on a recent Sunday, at least a dozen people passed through a $795,000 Morningside Heights two-bedroom fixer-upper, its walls gutted to the studs, within the first ten minutes of its open house. Daniel, a banker looking in the West Village, told me he’s lost five bidding wars in the past year. “The last apartment, every person who saw it made a bid,” he said.

The statistics, too, tell a story of rapid heating and expansion. The median price of a Manhattan apartment is $820,555, up 5.9 percent from a year ago, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel. Sales volume rose 6.3 percent. Demand remains high, with 3,066 properties going into contract in the first three months of this year, according to Streeteasy.com, a 15 percent jump from the previous year and the highest number of first-quarter contracts since the market’s 2008 meltdown. The high end of the market is particularly bullish—a penthouse on 57th Street sold for $90 million, and the penthouse at the Pierre is back in play, this time listed for $125 million.

But is this really a bubble? No, not really. The combination of desperate buyers, low interest rates, and rising prices may make things look a lot like they did back in 2006, but there are significant differences. This is a new kind of market, one that has more to do with what kind of a city New York has become than with the perils of easy money.

The last time around, loose credit drew speculators looking for a quick profit and buyers who couldn’t actually afford their mortgages, not to mention that New York was on a building binge. This time, lenders have become pickier, approving fewer new mortgages, and building has slowed. But just because it isn’t a bubble doesn’t mean it’s a healthy market.

Lenders’ caution has only added pressure to a second difference between now and seven years ago: There’s a significant inventory shortage. Miller Samuel found that in the first quarter of this year, the number of Manhattan listings dropped 34.4 percent to 4,960, the steepest year-over-year decline since the firm began tracking inventory in the borough. Brooklyn, too, is at its all-time low in five years; Queens, in eight years. Though the recession didn’t sink real-estate values to the degree it did in Florida or Arizona, it brought new construction to a near standstill. The number of permits issued for new housing sank from 33,911 units in 2008, the highest figure in decades, to 6,057 in 2009. Applications are on the rise again, with permits filed for 10,559 units in 2012, but it will take a few years for those projects to be completed. Those projects that have gone forward have mostly catered to high-end buyers. They were, after all, the ones still buying.

Meanwhile, New York continues to be an exceedingly popular place to live. Manhattan’s appeal has extended to the tips of the island. Brooklyn is now a worldwide brand, with industrial neighborhoods like Williamsburg and Greenpoint as desirable as Brooklyn Heights. As a whole, the city’s population has increased by 2 percent annually, adding 161,000 new residents in the last two years, more than four times the rate of increase a decade earlier.

Location: Bedford-Stuyvesant

Sq. footage: 3,200

Sold in 2001: $375,950

Sold in 2006: $989,000

2013 Asking Price: $1.35 million.Photo: Courtesy of Brooklyn Bridge Realty Ltd.

This trifecta of tight credit, low inventory, and high demand has created a highly segmented market, one that favors the cash-heavy and the affluent. Buyers like Ellen can’t buy a place without selling their apartments first—but if they sell, there’s no guarantee they’ll be able to close on a place they like, given the market frenzy. So holding on makes sense. First-timers like Daniel can’t get traction, because they need mortgages in a marketplace teeming with all-cash buyers. And then there are people like broker Donald Brennan’s clients, a couple who sold their two-bedroom co-op two years ago to free up a massive down payment for a townhouse. But Brooklyn townhouses have seen their prices go skyward, too. The couple ended up having to settle for a condo.

Prospective buyers are moving further and further out in search of an affordable property, but really, it’s getting expensive everywhere. In Crown Heights, the median price of two-bedrooms listed on Streeteasy.com is $425,000, out of reach for many in a city with a median household income of $51,270. In one sense, real estate here isn’t unaffordable, since clearly there are buyers out there, says the economist Chris Mayer, who teaches at Columbia University’s business school, but it has become “unaffordable to people who’ve lived here a long time.” They’re competing against high-net-worth Americans (both locals and pied-à-terre types) as well as foreign investors able to purchase mortgage-free. Brokers talk of an uptick in European, Brazilian, and Chinese clients.

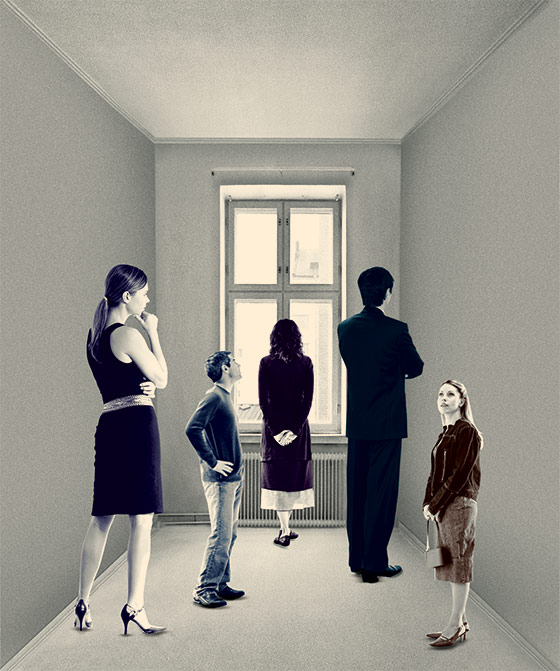

New Yorkers have been kvetching about the disappearance of old New York since there was a New York. But the real-estate market of this moment suggests that Mayor Bloomberg’s description of the city as a luxury product is becoming more and more true, especially in its most expensive provinces. Just as in the London neighborhood of Belgravia, many of New York’s most expensive apartments sit empty for much of the year, their superrich owners using them as vacation properties and safe investments instead of actual homes.

When so-called up-and-coming Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights are commanding mid-six figures for properties, it hardly makes sense to talk about gentrification anymore—it’s a new city, and in a lot of neighborhoods, even the gentry can’t find a place to live.

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].