Seymour Durst, the late Manhattan real-estate mogul, was said to believe a man should never invest in a property he cannot reach by foot. He was also a resourceful and inveterate debt scold, and something of a lyricist to boot. He regularly took out advertisements on the front page of the Times warning of looming fiscal calamity. (“Borrow, borrow; enjoy tomorrow today,” he wrote in one. “Tomorrow will be terrible.”) Once, he mailed New Year’s Eve cards to Congress reminding each legislator how much he or she owed toward the federal deficit.

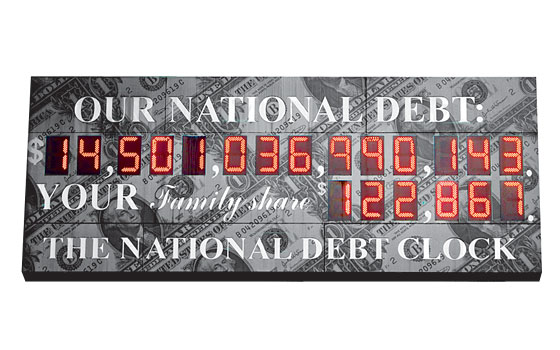

In 1989, Durst paid Artkraft Strauss $100,000 to build him his masterwork: a 21-foot-wide metal-encased federal-debt odometer, which he hung off the side of a building not far from Times Square. The National Debt Clock remains an effective piece of agitprop, its running tallies of the total debt (some $14 trillion) and the portion theoretically owed by each American family ($122,000, give or take) a reminder of exactly how deeply the country has fallen into the red. Just last month, Tom Reed, a Republican congressman from Corning, proposed that a facsimile be erected on the floor of the House.

In fact, interest in the National Debt Clock tends to be cyclical, Douglas Durst said the other day. The morning was brisk and cloudy, and Durst, who took over the family business, and the clock, from his father, was standing in the courtyard of 1133 Sixth Avenue, where the current iteration of the device—complete with a shinier façade and a higher-resolution display—was installed in 2004. He was wearing a dark suit and a blindingly blue Thomas Pink tie spackled with small golden elephants. “I got it for a Republican fund-raiser,” he explained, jamming his hands into his pockets.

Durst, who is bell-shaped and balding, turned to Jordan Barowitz, the director of external affairs at the Durst Organization. Barowitz recalled that he had recently spoken to a reporter from the Russian network RT. “Historically, the clock is most important when no one is thinking about the debt,” Barowitz said solemnly. “It’s this silent vigil, churning away.” (Or at least most of the time: In 2000, when the deficit was shrinking, the clock was unplugged and covered with a curtain of red, white, and blue.) A gaggle of French tourists wandered by, snapping photos of the clock as they went. “C’est beaucoup d’argent,” someone suggested. “Beaucoup,” agreed another.

For all the clock’s ostensible exactitude, Barowitz confessed that most of the time, the numbers it displays are actually estimates produced by a computer algorithm; once a week, technicians from Clear Channel must “true” the clock to the real debt figures. In his day, Seymour Durst, a hands-on sort, would reportedly crunch the numbers from his nearby office and update the clock by modem. “When people asked about his politics, he would say he was a monarchist,” Durst said of his father. He paused, taking one last look at the clock. “Maybe I’m turning into a monarchist too.”

A few minutes later, a cameraman from Bloomberg News showed up. The station was switching to an HD feed, and he needed to get some new stock footage. The cameraman remembered when the clock had fewer digits—in 2008, the debt outran the capacity of the machine, and the Durst Organization had to rejigger the display. He confided his own deficit-reduction plan, whose illogic did not dampen his enthusiasm for it. “I think everyone in the country should take out a loan for exactly $122,000. We won’t pay the banks back, and when the banks go under, we’ll refuse to bail them out. Problem solved!”

Across the courtyard, a janitor leaned up against a wall and palmed a cigarette from a pack of Marlboro Reds. He said he had worked in the building for seventeen years but paid the clock little heed; his thoughts were occupied by more immediate concerns. “I don’t think about it.” Never? “Never. I think about my own pocket. Besides,” he added, cocking one ear toward the clock, which whirred quietly overhead, “who has that kind of money?”

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].