On Saturday, January 9, Rupert Murdoch was on his Boeing 737 returning to New York from a business trip to Los Angeles when he learned that the New York Times had just posted a long profile of Fox News chief Roger Ailes on its website, one that he knew was going to cause a giant headache.

Earlier that morning, Murdoch’s son-in-law Matthew Freud, the London PR executive who’s married to his daughter Elisabeth, had sent an e-mail to Murdoch’s BlackBerry (Murdoch only recently began using e-mail himself). “I’ve given a quote to the New York Times, and you’re probably not going to like it,” Freud wrote.

The quote lived up to its advance billing—and quite a bit more. “I am by no means alone within the family or the company in being ashamed and sickened by Roger Ailes’s horrendous and sustained disregard of the journalistic standards that News Corporation, its founder and every other global media business aspires to,” Freud, the great-grandson of Sigmund, had told the paper. Certainly there was personal animus in the remark; in the left-of-center London social circles where Freud and Elisabeth operated, Fox is particularly loathed.

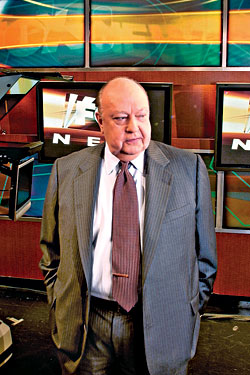

But the quote was also a salvo in a battle that had been raging around Murdoch for years. Is Fox News a disreputable cash cow, its reported $700 million in profit something to be tolerated with a held nose? Or is it central to the News Corp. mission? And questions like these lead directly to others: Who is Rupert Murdoch, really? And what does he want now?

As always, these questions do not lend themselves to simple answers. The News Corp. patriarch turns 79 years old on March 11. The younger generation—Prudence, 51; Elisabeth, 41; Lachlan, 38; James, 37—is no longer that young. Three of its members are accomplished businesspeople in their own right. And they, along with senior News Corp. executives, have been working toward the day when Rupert is no longer making the decisions. They are trying to shape and define his legacy, sometimes editing out parts, like Roger Ailes and Fox News, that offend their sensibilities, while trying to position the company for a future that looks very different from the present. But the problem with these efforts is that Rupert Murdoch is not going anywhere. If anything, he’s been more active than ever, raging at his adversaries with the vigor of a man half his age. Over the last several months, he’s been waging a very public war with Google, trying to bend the freewheeling web according to his own rules. He successfully fought Time Warner to get the cable giant to cough up millions to broadcast his Fox affiliates. And he’s rebuilding The Wall Street Journal with an eye on destroying the New York Times, one of the most ancient of his enemies.

For Murdoch, these conflicts amount to holy missions. While others may see him as an opportunistic predator, ready to lay waste to whatever falls under his gaze, Murdoch sees himself as a moralist, the enemy of entrenched, arbitrary power. (Indeed, many of his newspaper wars, from the Times of London vs. the Daily Telegraph to the New York Post vs. the Daily News, have been financial debacles for both parties involved.) Google and the Times may be on opposite ends of the media spectrum, but they share an arrogance about their place in the world. And Murdoch, from the beginning, has found purpose in teaching such institutions hard lessons. Many see his pursuit of the Times as an irrational atavism, a figment of his past. Yet if the Times is going to fall, he wants not only to hasten its destruction but also to be there to dance on the rubble.

When Murdoch landed in New York around 2 p.m., he called his chief spokesperson, Teri Everett. A release went out saying that “Matthew Freud’s opinions are his own and in no way reflect the views of Rupert Murdoch, who is proud of Roger Ailes and Fox News.” He spent much of the weekend at his apartment at 834 Fifth Avenue—Laurance Rockefeller’s former triplex, which he and his wife, Wendi, had purchased for $44 million in 2005. All things considered, there was much to be pleased about. 20th Century Fox’s Avatar was on track to earn $2 billion, which would make it the highest-grossing film of all time. He had survived a crippling media recession and was licking his chops at the prospect of launching a good old-fashioned newspaper war. And yet the Freud quote was still gnawing at him. “Here he is at the height of his powers, and all anyone wants to talk about is this one quote. He finds that incredibly frustrating,” a senior News Corp. executive recently recalled.

Murdoch, who depends on Ailes’s profits to fund his unprofitable hobbies (the New York Post, for instance, which has failed to take down the Daily News and is said to lose as much as $70 million a year), didn’t want Ailes to do anything rash, like quit. His feelings about Ailes were complicated, but he needs him. (Just as he needs his children, but gets furious at their efforts to usurp control.) And so inside News Corp., Murdoch worked to quell the little family rebellion. On Monday, while Ailes was having lunch with News Corp. chief operating officer Chase Carey in the third-floor executive dining room, Murdoch made an impromptu visit. Both James and Elisabeth sent Ailes e-mails explaining that Freud’s views weren’t their own. Everyone had fallen into line. Rupert Murdoch was still in charge.

The Freud quote was not the first time in recent memory that Murdoch had choked on his morning Times. On June 10, 2007, Murdoch opened the Gray Lady to read an editorial about his planned takeover of the Journal. “Frankly,” the piece intoned, “we hope the Bancrofts will find a way to continue producing their fine newspaper, or, failing that, find a buyer who is a safer bet to protect the newspaper for its readers.”

Murdoch was infuriated by the editorial, which he saw as yet another example, as if more were needed, of the Times’ characteristic self-interest wrapped in a cloak of high-toned moralism. The previous night, he had run into Times chairman Arthur Sulzberger Jr. at a party on Barry Diller’s yacht, and Sulzberger had assured him the piece wasn’t “faintly anti-Murdoch,” as Sarah Ellison reports in her upcoming book, War at the Wall Street Journal. Murdoch wrote Sulzberger a personal note the next morning that concluded: “Let the battle begin!”

The next day, Sulzberger was sitting in his office at the Times Building with Richard Beattie, the chairman of law firm Simpson Thacher, who had advised the Dow Jones board during the Journal deal. Sulzberger pulled out Murdoch’s note. “He was laughing at the time,” Beattie told me. “He thought it was cute.” Sulzberger never replied to Murdoch’s letter. When I called Sulzberger to ask about the competition with the Journal, he dismissed my question out of hand: “Whatever,” he said.

“I’ve given a quote to the New York Times, and you’re probably not going to like it.” — Murdoch’s Son-in-Law Matthew Freud

Murdoch had coveted the Journal for as long as anyone close to him could remember, and he stalked it through the middle of the last decade, even when it became clear that the newspaper industry’s fortunes were in an irreversible spiral. Some see an Ahab-like obsession in Murdoch’s pursuit of the Times. “[Buying the Journal] was the worst deal he ever did. It never made sense,” a former senior News Corp. executive says. “He had no justification for why he should buy it—he just wanted it.”

Financially, the $5 billion acquisition couldn’t have been worse. Last year, News Corp. announced it was taking an embarrassing $3 billion write-down on its newspapers, effectively suggesting it overpaid for the Journal by half. But for Murdoch, financials are always facts to be managed, rationalized by other means. Building the Journal into a general-interest newspaper to take on the Times is a crusade. Arthur Sulzberger himself is, for Murdoch, a symbol of the Times’ hypocrisy, its smugness, and its shortcomings. Murdoch’s hatred of the Times is a product of his long-standing class antagonisms rooted in his early days as an Australian building an empire in London. But on a more fundamental level, he believes Sulzberger is a poor businessman who has mismanaged his company’s fortunes and deserves to lose.

Robert Thomson, whom Murdoch installed to run the Journal in May 2008, shares the belief that American journalism in general, and the New York Times in particular, is hidebound and decadent. “There are two personnel moves at the New York Times that I think make them vulnerable,” Thomson tells me. “One is Mr. Sulzberger remains in place. And the second is that Howell Raines lost his job. Because whatever Howell Raines’s sins were, he was clearly a reformer. And he was prepared to confront the journalistic elite at the paper and bring the New York Times into the modern ages. That process really stopped when Howell left.” (Raines’s successor, executive editor Bill Keller, declined to comment for this story.)

About a decade ago, Thomson and Murdoch had become close. They are both married to Chinese natives, and the couples vacation together on Murdoch’s yacht. In 2001, as a top editor at the Financial Times, Thomson was passed over in his bid to run the paper. He felt betrayed and quit the FT five months later to work for Murdoch as editor of the Times of London.

Thomson’s views of journalists are closely aligned with those of his boss: He thinks most of them are liberals overly concerned with writing stories that will impress other liberal journalists and win prizes in journalism competitions. With a pronounced stoop brought on by arthritis in his spine, Thomson is something of an awkward leader, “a wimpy nerd,” as he described himself in a recent speech. His gaunt frame is accentuated by a wardrobe of shiny, narrow-cut suits paired with skinny ties. He tempers this ungainly presence with a wry, self-effacing manner and a habit of laughing at his own jokes.

Historically, the Journal had treated general news as a commodity for other papers to cover. Instead, it focused journalistic muscle on its deep financial coverage, with a specialty in long narrative articles chronicling boardroom struggles as epic sagas of greed and ambition. While it owned the business beat, its front page was a hybrid of a magazine and a newspaper, defined by its subdued headlines and hand-drawn illustrations. Paul Steiger, the Journal’s longtime editor, used to say that the Journal was a “second read.”

Murdoch and Thomson flatly despised this conception. With newspaper circulation and advertising in retreat, they believed readers had little time for one paper, let alone two. To win, the Journal needed to become an aggressive, general-interest newspaper that would grab readers’ attention at the newsstand and assault the New York Times as the country’s preeminent agenda setter. Over the past year, Thomson, following Murdoch’s direction, made dramatic changes to the paper, insisting on shorter stories and covering natural disasters and plane crashes. The transition was jarring. “What is this, a high-school newspaper?” one reporter recalled thinking after an editor sent out an assignment to cover a shooting in upstate New York last spring. The strategy has allowed the paper to make some modest inroads, especially in cities, such as San Francisco, for instance, where the local paper has struggled in the new media environment. But the danger is that redefining it as a general-interest paper—an upscale, edgier USA Today—risks alienating its exceptionally affluent core audience and surrendering its advantage as a business paper.

The paper’s evolving politics don’t seem designed to attract the Times’ well-to-do center-left readership, either. Under Thomson and his deputy, Gerry Baker, a British neoconservative and former columnist for the Times of London, the Journal shed its midwestern roots (both its legendary editor Barney Kilgore and its former star James B. Stewart are DePauw University alums). Now reporters check the FT and Times of London websites each morning. Thomson believes that his reporters should be “feisty, not lapdogs with laptops or meek members of a political movement.” With this shift came a new political viewpoint: not conservative, necessarily, but oppositional to the prevailing media Establishment led, in Thomson and Baker’s view, by the liberalism of the Times and the Washington Post. Editors insist that reporters identify sources’ political affiliations.

Baker was charged to oversee the Journal’s political coverage, an assignment that raised eyebrows. As a columnist, he had championed Sarah Palin, labeling Obama a “greasy-pole climber” while writing that Palin’s “experience … enables her to understand the concerns of most Americans.” Baker’s views appalled many at the Journal. During a tense meeting with the paper’s Washington staff in November 2008, one reporter told Baker that the Journal’s news pages were supposed to be a political counterweight to the paper’s rabid right-wing editorials. Baker began telling people that he saw his role as policing the Journal’s coverage. “Our emphasis is on straight reporting,” Thomson says. “If that happens to be seen as not progressive enough, then indeed it is unconventional wisdom.”

On the seventh floor of News Corp.’s midtown headquarters, largely in secret, Murdoch began building what he sees as the ultimate Times-killer. Next month, if all goes according to plan, the Journal will launch an eight-to-sixteen-page metropolitan section that will directly challenge the paper of record on its home turf. “New York will be the next phase of the transformation,” Thomson tells me. The Journal has signed on Bloomingdale’s and Bergdorf Goodman as new advertisers and is said to be spending $15 million on the venture, dubbed “Project Amsterdam.” At a time when a national audience is the one coveted by most advertisers—and when local news is less profitable than ever—it seems a quixotic business proposition, at best. But this assault has very little to do with business. “He’ll be completely irrational about spending,” a person close to the company says. “It’s a spear-thrust right at the Times, intended to embarrass and bleed the Times,” a senior Journal editor explained. If anyone doubted the New York section’s centrality to the Journal’s mission, Thomson seated the metro desk right near his office at the front of the newsroom. “The idea of the New York Times as a burning, sinking ship is something they fantasize about at night,” says the senior Journal editor.

The New York section is run by John Seeley, who, as managing editor of the New York Sun, had earned the nickname “Iron Man.” Several other new employees are refugees from the defunct conservative daily, which was chiefly a mix of highly competent small-bore metro stories, right-wing opinion, and eclectic cultural criticism.

Murdoch had long been an admirer of the Sun, a succès d’estime among some conservatives that never attracted a significant New York readership or advertising base. In September 2008, during its death throes, he even considered buying the paper, hosting a breakfast meeting at News Corp. headquarters with the Sun’s editor, Seth Lipsky, and investors Bruce Kovner and Tommy Tisch. But Murdoch had cooled to the idea a few weeks later. “The Sun’s going to close,” he told Ken Bialkin, a lawyer who was advising the failing paper, according to a person familiar with the talks. “Maybe I’ll hire Lipsky as a columnist. But I have my hands full here.” Instead of buying the Sun, he seems to be building a replica of it, to be inserted into the Journal.

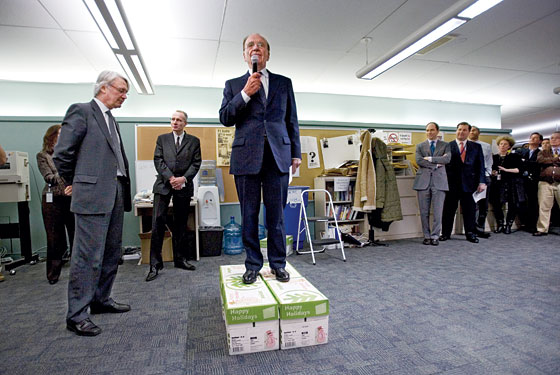

Shortly after the Journal deal closed in December 2007, Murdoch appeared before shell-shocked staff, standing on a stack of printer paper like a general addressing a vanquished army. “The message was clear,” one reporter in the room remembers. “It was: ‘You’re a bunch of lazy, self-important, past-their-prime journalists.’ ” The Journal’s then–managing editor, Marcus Brauchli, and senior Journal executives stood off to the side. Four months later, Brauchli was forced out of the job, leaving with a reported $6.4 million in severance.

But having humiliated them—and pushed many of them out—Murdoch is assimilating the remaining staffers into his merry band of raiders. He has a deep, instinctual belief in the power and importance of newspapers and the wherewithal to continue to invest in them (Dow Jones is a tiny part of his business, amounting to 3 percent of News Corp.’s total revenue). Murdoch has made the Journal feel like the center of his universe. He spent $80 million to transform four floors of News Corp.’s office tower into a state-of-the-art newsroom for the Journal. It is something of a showpiece. At the center of the cavernous space is a cluster of desks and computers known as “the Hub,” a Star Trek–like bridge where top editors pilot the paper’s 24/7 mission. Around the room, flat-screen televisions broadcast Fox News and the struggling Fox Business Network (“We’re doing our bit to help Fox Business,” Thomson joked to his staff). Digital clocks display the time in Singapore, New York, and London. Coffee machines are stationed throughout the floors, and the annual coffee budget runs $100,000. The newsroom buzzes with a confidence unusual for these times. “I didn’t go into journalism in 1975 to end up working for Rupert Murdoch,” David Wessel, the Journal’s well-regarded economics editor, told me, “but it sure turns out to be nice to have a deep-pocketed owner at this time in the industry.”

“Buying the Journal was the worst deal he ever did. It never made sense.” — A Former Senior News Corp. Executive

Murdoch’s strong attachment to the Journal has engendered support in surprising quarters of the journalism Establishment as many have reconsidered their anti-Murdoch views. “It’s a much livelier paper,” says Daily News owner Mort Zuckerman, Murdoch’s onetime tabloid antagonist. (Murdoch and Zuckerman have, for the time being, laid down their swords—Murdoch, a businessman to the core, can make peace as easily as he makes war. In a move that has many different possible meanings, the New York Post recently cheered on Zuckerman’s possible Senate run.)

“Hats off to Murdoch; he’s serious about print journalism. He’s the last guy standing who believes in it,” says former Times executive editor Joe Lelyveld. “Arthur [Sulzberger] is the guy who said a few years ago he didn’t know if the Times will be standing as a print newspaper.” When I asked Lelyveld if he thought his former boss Sulzberger believed in the value of the Times’ print edition, he grew quiet. “I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t want to answer that question.”

In October, Rupert and Wendi Murdoch attended a party for Times columnist Nicholas Kristof and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, at the Times Building to celebrate their book Half the Sky. Rupert had arrived late and walked into the building alone. Wendi was already up on the fifteenth floor mingling with Keller, Sulzberger, and other Times luminaries. Staffers did a double take when Murdoch walked straight past the security desk and the turnstiles mysteriously opened for him, as if he owned the place. “He just went right through,” one bewildered Times staffer told me. “There was this feeling he was walking right into the lion’s den.”

Earlier this month, I visited the Times to see how it’s confronting the Murdoch threat. In December, Times media columnist David Carr published an article alleging that the Journal is veering rightward. Thomson responded with a statement and attacked the piece as “more evidence that the New York Times is uncomfortable about the rise of an increasingly successful rival while its own circulation and credibility are in retreat.”

Times executives believe Murdoch is practicing his well-established tactic of slashing advertising rates to bleed competitors dry, and the Times’ strategy is to hold the line. “We’re not doing irrational things,” says Times president and general manager Scott Heekin-Canedy. (A Journal spokesperson says, “We have not dropped our rates at all.”) The Times doesn’t want to let Murdoch frighten it into making a mistake. Earlier this winter, executive editor Bill Keller put managing editor Jill Abramson in charge of a committee tasked to review the paper’s New York coverage. Abramson told me that the paper is satisfied with its metro coverage and isn’t planning any drastic countermoves. “I don’t want to sound like some stodgy Timesman of yore by saying the Times is unmatched and sounding arrogant, but I really believe we are unmatched,” Abramson told me. For Abramson, the rivalry with the Journal is personal. She spent a decade at the Journal’s Washington bureau before joining the Times. “I grew up on the Upper West Side. The Times subscription was a religion in our home,” she says. “It was disappointing for the ten years when I worked at the Journal. My parents didn’t subscribe, and my uncle at Lehman Brothers had to call them up to tell them to go down and get the paper whenever I had a story on the front page.”

Thomson, predictably, is contemptuous of Abramson’s efforts. “They are better than the Chinese Communist Party at committees,” he tells me. “I’m sure they’ll always find what they’re doing at the New York Times is perfect. As far as I’m concerned, I’m glad they’ve reached the conclusion that what they do now can’t be improved.”

But Abramson has a point. Whatever one thinks of the Times’ metro coverage, it can’t be denied that their aggressive reporting brought down one governor (Spitzer) and, last week, annihilated David Paterson’s career as well. More broadly, the Times is religion for a particular brand of reader and advertiser. While the Journal’s circulation rose last year, bucking industry trends, Murdoch may not grasp the Times’ appeal to its core audience, for whom the characteristic Murdochian worldview is a sign they should look elsewhere. Among the well-to-do, gray stolidity can even be a virtue.

The Times is an ancient enemy of Murdoch’s. Google is a much newer one. On the afternoon of February 2, Murdoch was on the phone with stock analysts and journalists to spin News Corp.’s second-quarter earnings—a remarkable $254 million second-quarter profit, especially impressive considering that the company lost $6.4 billion in the same quarter last year. Many old-media figures are wringing their hands these days, staring at plummeting revenue charts, waiting for the world to end. Not Murdoch. He was boastful and wildly animated. “Content is not just king, it is the emperor of all things electronic,” he announced. He sees the struggle to control the shifting media landscape in deeply personal, even spiritual terms. “Without content”—without him, he seemed to be saying—“the ever larger and flatter screens, the tablets, e-readers, and the increasingly sophisticated mobile phones would be lifeless.”

Murdoch has a particular animus against Google. He believes the search giant is stealing his content while wrapping itself in that familiar cloak, albeit one with New Age–y Silicon Valley stylings: “Don’t be evil.” Much as he has done in the newspaper wars he’s fought over the last 60 years, he wants to turn the tables, call Google’s moral authority into question. At its core, Murdoch’s fight is about getting Google to pay to put his content into the search index. Publicly, Google treats this as a nonstarter. “We’re not going to pay for indexing,” says Josh Cohen, the head of Google News. “It’s something we just don’t do.”

Before Murdoch realized that Google posed a mortal threat to his empire, he used to praise it, recalls one former News Corp. employee. “We would be sitting in meetings, and he’d go on and on about the Google guys, and how they had dry cleaning and massages, and what a great company and culture it was,” the staffer recalls. When he bought the Journal, Murdoch thought about making online content free, even though the Journal was one of the few successes in fee-based news sites. And Murdoch and Wendi are friends with Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, though they are not as close lately, given the heated nature of their conflict.

Last year, Murdoch and his senior executives decided they needed an organized counteroffensive. As a code name, they chose Project Alesia, named after Julius Caesar’s victorious siege of the Gallic forces in 52 B.C. Murdoch conceived the fight against Google as a political campaign. He mapped out distinct phases. First, Murdoch and Thomson would make a series of provocative speeches to drum up press, using News Corp.’s media outlets and other interview opportunities to shape the debate. In February 2009, during an appearance on Charlie Rose, Thomson said, “Google devalues everything it touches.” In April, Thomson said in an interview, “Certain websites are best described as parasites or tech tapeworms in the intestines of the Internet.” And in December, Murdoch published an op-ed in the Journal declaring that “there are those who think they have a right to take our news content and use it for their own purposes without contributing a penny to its production … To be impolite, it’s theft.”

The inflammatory rhetoric generated a flurry of press and laid the foundation for the announcement that News Corp. would begin charging for its online content. Last year, he hired Jonathan Miller, the former CEO of AOL, who, along with Murdoch’s son James, is leading a team of senior executives to develop an online pay model while negotiating an accord with Google. The plan, which is still evolving, envisions bundling all of News Corp.’s newspaper content and partnering with other publishers to deliver it to mobile devices and the coming crop of tablets. James, according to executives involved in the discussions, believes readers will pay for bundled content like viewers pay for cable television. “It’s very much like a cable thing,” one News Corp. executive explained. “If 5 million people around the world are willing to pay, that changes the economics of the industry.”

Meanwhile, Miller has also been in talks with Microsoft about possibly pulling all of News Corp.’s content from Google and signing an exclusive distribution deal with Bing. And if talks with Google break down, Murdoch is readying a lawsuit against them. “He’s pretty tightly wound up over Google and has been ready to sue them,” says a senior media executive who recently conferred with Murdoch. “He doesn’t trust them at all.”

Murdoch’s defiance invited speculation that he had lost it. And continued trouble at his MySpace division furthers this view. “Digital is out of his comfort zone,” a former senior MySpace executive says. “It’s much more the Wild West. He gets the raw-competition part of it, but he’s never been in a place where the business model isn’t clear. The destruction is just happening so fast.”

“Hats off to Murdoch. He’s serious about print journalism. He’s the last guy standing who believes in it.” —Former Times Editor Joe Lelyveld

After Murdoch concluded his remarks on this month’s earnings call, the line was opened to journalists’ questions. The first came from a writer from the Guardian, the liberal British paper that is a vocal proponent of giving away its content on the web. “I wonder what you think of people who think that newspapers are sleepwalking into oblivion if they feel that they can buck an irreversible trend of content becoming free?”

“I think that sounds like b.s. to me,” Murdoch said.

“So you think that free-content strategy is not going to work?”

The operator called on the next reporter. This discussion was over.

As Murdoch shores up his barricades and directs his raiding parties, his ambitious adult children wait, often restively, for their chance to lead. Rupert, intentionally or not, hasn’t always made it easy for them. His daughter Prudence has never played a substantial role in the family business. In 2000, Elisabeth, unhappy at BSkyB, the British pay-television service in which Murdoch holds a 35 percent stake, left the company and branched out on her own. (Her firm, Shine, is a tremendously successful television production house.) Lachlan walked away from the throne in 2005, resigning as deputy COO of News Corp. after clashing with Roger Ailes and then–News Corp. president Peter Chernin, feeling that his father wouldn’t back him up.

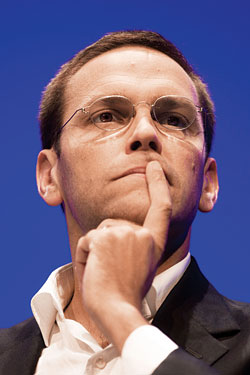

That leaves James as heir apparent. James became aware of the pressures of being a Murdoch from a young age and developed a suspicion of the press. As a 15-year-old intern at the Sydney Mirror, one of Murdoch’s papers, he was photographed dozing on a couch during a press conference. The rival Sydney Morning Herald trumpeted the photo on its front page the following day. Born in London and raised in New York, James had a peripatetic childhood. He attended Horace Mann, an intellectual hothouse filled with children of New York’s elite, yet he never made much of his family’s famous name, preferring an outsider, artist persona. James was into music and wore long black wool trench coats and Chuck Taylors. He bleached his hair blond. “He was that type in the John Hughes movie that was the really cool, aloof guy,” a schoolmate recalls.

James studied film at Harvard and briefly roomed with Jesse Angelo, who would go on to become managing editor of the New York Post. But James dropped out shortly before graduating and, along with a pair of Horace Mann classmates, launched Rawkus, a hip-hop label that put out groundbreaking acts like Mos Def and Talib Kweli. For a moment, it looked like James would pursue a career outside the family empire.

But Rupert lured him back. In 1996, he bought Rawkus and installed James to run News Corp.’s fledgling dot-com ventures. James became something of an evangelist for the Internet. He inhabited the image of a new-media intellectual, favoring tailored black suits and thick-framed glasses. An interviewer for The Industry Standard in a 1999 profile noted that a copy Don DeLillo’s Underworld and the latest issue of Granta were in plain view in James’s Chelsea offices. But when the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, News Corp. gutted its Internet division. The leftover furniture was transferred to its book publisher HarperCollins.

The spectacular failure of News Corp.’s Internet businesses tainted James in the eyes of company executives, who naturally wanted to find fault in Rupert’s insistence on continuing the Murdoch dynasty. In May 2000, James headed to Hong Kong to run Star TV, Murdoch’s fledgling Asian pay-television service. Rupert appointed Lachlan to be deputy chief operating officer of News Corp., a move everyone recognized as evidence of Lachlan’s unrivaled status. James expressed resentment that Lachlan had been the anointed one, and he worked to make it clear that he was the smartest of the three children. At board meetings, James and Lachlan got into arguments over business decisions. “There was always banter going on,” a former senior News Corp. executive recalls. James, the sharper debater, could be arrogant and profane, peppering his declarations with “fuck,” much to his mother Anna’s dismay.

The brothers had always been fiercely competitive. Lachlan was the outgoing son, more like Anna. James, people thought, was much more like Rupert: an introvert. When Rupert married Wendi Deng only seventeen days after divorcing Anna in 1999, it was James who played conciliator, shuttling between parents. Lachlan sided with Anna.

When James arrived at Star, the perception among the senior executives, according to one senior employee, was that he needed to be rehabilitated after the Internet’s bust. “The feeling was James was the mistake maker,” a former senior Star executive remembers. “We felt Daddy needed something for him to do. He was the poor second son, and this is going to be a nightmare.”

Whatever lingering resentments remained, James swallowed his ego and worked to learn the television business. During his early weeks on the job, he went around to meet as many executives as he could and asked detailed questions. But as much as he reached out to his team, James kept his staff at a distance. His brother, Lachlan, was known as a gregarious boss. At the New York Post, where he was publisher, Lachlan was a popular figure in the newsroom. In Hong Kong, James never warmed to the public side of his job. “He’s cool to the point of cold,” one former News Corp. executive says.

In 2003, James left Star and became CEO of BSkyB. The appointment was controversial—James was only 30 at the time—but James again demonstrated his resolve. At BSkyB, his business instincts emerged. Like his father, he could make gut decisions and seemed to relish provocation. But James’s smartest maneuverings were directed at his own rise within News Corp. For the past decade, James has remained on the outer reaches of News Corp.’s empire, leaving Murdoch’s power base in New York unchallenged. He stayed out of the press and reportedly told his PR adviser that he would be successful at his job when people began referring to him as the “reclusive James Murdoch.” “He saw the risk of hanging out next to his dad in New York,” a person close to James says. James astutely avoided Ailes and Peter Chernin, who both maintained significant power centers of their own and were responsible for driving Lachlan from the company. When Lachlan quit, James absorbed the message. “James played it so right,” a former senior News Corp. executive says. “He had left the country, and he established himself.”

James differs from his father in significant ways. For starters, he has an M.B.A.-style view of management. As part of this corporate sensibility, James is attuned to News Corp.’s image and cares deeply how the company is perceived—it bothers him that it is seen as downscale and predatory. During the Journal acquisition, James reportedly told his father to pull out of the deal because of all the negative press. Part of this is James’s sensitivity. But as a would-be inheritor to the throne, James needs News Corp. to be respected by Wall Street. The Murdoch-family trust controls 38 percent of News Corp.’s voting shares. For it to remain in control, the company needs to be perceived as a professionally managed concern.

Roger Ailes is another complication for James. In Europe, where James spends much of his time, Ailes and Fox News are mocked and loathed as the worst form of American jingoism. James is concerned about climate change, and his wife, Kathryn, a former model and marketing executive, works for the Clinton Foundation. Politically, James is not liberal—he’s a committed free-market thinker—but Fox’s brand of politics is a problem that, in his view, needs to be managed.

James ultimately came to see Rupert’s purchase of the Journal as an opportunity: It would be a retirement project for his father. The paper’s prestige would help News Corp., and Rupert’s devotion to it would allow James to gain a more central role at News Corp. Indeed, a week before the Journal deal closed, James was promoted to run all of News Corp.’s businesses outside the United States.

“When they were doing the Journal deal, the children looked at it, especially James looked at it, as a way to deflect Murdoch’s attention,” says Michael Wolff, who wrote a book, The Man Who Owns the News, about Murdoch. The book, based on hours of interviews with Murdoch and many of his lieutenants, itself became a flashpoint within News Corp. Over nearly a decade, Gary Ginsberg, a member of News Corp.’s inner circle and Murdoch’s communications adviser, had worked tirelessly to soften and massage Murdoch’s image and had done a remarkable job of making News Corp., if not exactly admired, then palatable to a certain swath of Manhattan and Wall Street. In October 2007, Ginsberg, a former lawyer for the Clinton White House, was promoted to run global marketing for News Corp.

Ginsberg, along with Matthew Freud, was involved in dealing with Wolff on the book. (Murdoch didn’t need convincing to grant Wolff access. He had been impressed by a Vanity Fair column Wolff did about his purchase of the Journal and had passed it around to News Corp. board members.) But ultimately, much of what Wolff wrote infuriated many camps inside News Corp. When Ailes read Vanity Fair’s excerpt of the book, which recounted how embarrassed Murdoch was by Ailes and Bill O’Reilly—a view Wolff says came from interviews with Rupert—Ailes became enraged. “Is this true?” he demanded in a September 2008 meeting.

“No, it’s not true,” Murdoch replied, assuring Ailes he was happy with Fox News and signing him to a new five-year contract.

James was unhappy about the book. Even before Rupert agreed to do it, James felt Wolff was the wrong writer to do the book and didn’t bother to read much of it when it was published. He believed News Corp. needed to be understood as a global company, and yet despite all the access Wolff had been granted, News Corp. was reduced to a circus of clashing egos.

James began to blame Ginsberg for mishandling Wolff’s book. But in some ways, this was only a pretext—an opportunity for James to gain more control over News Corp.’s corporate structure. Chernin’s announced departure in February 2009 created a leadership vacuum at the top of the company, and James quickly moved to fill it. “What James figured out is, whoever controls the press and investor relations controls James’s image,” one person close to Ginsberg says. “James knew Gary’s allegiances.” Last year, soon after the Wolff book was published, James told Rupert that he wanted Ginsberg out. Rupert resisted his son’s effort to manage personnel. But when Ginsberg got word from his friend Freud that his job was in doubt, he offered Rupert his resignation, despite having just signed a new five-year contract. Rupert didn’t resist and paid Ginsberg millions to go.

Perhaps emboldened, James then tried to move one of his key players from London into the company’s inner circle. He had already gotten his human-resources director moved to New York in 2007, and now James wanted his own London-based PR adviser, Matthew Anderson, to head up marketing and investor relations from New York. (In a phone conversation, Anderson says he never sought a role in New York.) This was a step Rupert would not tolerate. He rejected James’s move out of hand.

James’s rapid ascent comes with major risks. His father is by no means ready for the pasture, however obsessive and retrograde his enthusiasms, and members of Rupert’s inner circle wonder if he recognizes James’s power grabs. “James will need to be careful,” a former executive says. “As he moves into the orbit of the Sun King, the more chance you have of getting burned. The challenge is not to outshine Dad. James can’t ever put Rupert into a position where he’ll be forced to stop something or do something he doesn’t want to do.” News Corp. executives were surprised when, in January, Saudi billionaire Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, News Corp.’s second-largest shareholder, endorsed James to be Rupert’s successor. But as much as James wants the succession question closed, it must be frustrating for the would-be heir that Rupert keeps his options open. Earlier this month, Rupert took Lachlan on a sailing trip in the South Pacific along with Ailes. It was Ailes and Lachlan’s first reunion since they clashed five years ago—a surprising move that reignited speculation that Rupert is trying to repair relations and bring Lachlan back into the empire. Elisabeth, too, is hovering in the background. “I think all three of them will be in the company,” says a former executive who is close to the family. “Someone once said to me, ‘If you add Lachlan, James, and Elisabeth up, you get Murdoch.’ ”

“The challenge for James is not to outshine Dad.”

Some who have worked with Murdoch sense a perilous moment for the empire, a sadness even about what might become of his dynasty. Andy Steginsky, an informal adviser who helped Murdoch on the Journal deal, told me Murdoch was upset that, in the end, the Bancroft family unraveled. “Early, when it appeared the only way [the Journal] would be bought was a big family feud, he said, ‘I don’t want to cause a family feud,’ ” Steginsky remembers. “How could you feel good about it? It wasn’t the route he hoped the family would take.”

“Those of us who care for Rupert, and I do very much, hope we don’t get the fifth act of King Lear,” says David Yelland, former editor of Murdoch’s London tabloid the Sun, now a partner with the Brunswick Group. “You won’t find anyone to say anything critical about James Murdoch on or off the record. But the moment Rupert goes, that changes. Once he does pass, it will be very difficult to keep the company together. I almost wonder if he senses that and, toward the end of his life, we’ll suddenly wake up one morning and we’ll see an announcement he’s taking it private, or merge it with Google, or Microsoft, or [Liberty Media’s chairman] John Malone.”

For the Journal, the worry is that no future owner will have Murdoch’s bond with print. “We’re all hoping Rupert lives for a long time,” one reporter told me, “at least long enough for us to figure out a game plan. Everybody just assumes James or whoever would succeed him would not have the love for this property that he does.”

A couple of weeks ago, I spoke with Murdoch’s mother, the remarkable Dame Elisabeth Murdoch. When I reached her by phone, it was the day after her 101st birthday. Rupert had flown in to celebrate with her. She is still sharp and spends her time at Cruden Farm, the seat of the Murdoch dynasty, outside Melbourne. Rupert, she says, has “been a very good son … I’m full of energy, and so is Rupert!”

I ask her if he’s changed over all these years. “He hasn’t changed,” she says. “I think he’s happy. It’s hard to say. I think he’s thinking he’s doing a good job, and he’s a family man.”

Rupert and Dame Elisabeth have had their differences. His divorce from Anna was a particularly difficult experience. “I hardly know [Wendi] at all,” she says. “I’m very fond of Anna. I was very upset when they split. But there we are, it’s history now.”

I ask about the future and her grandkids’ role in the company. “They’re all capable,” she says. “It’s really hard to say [who will run the company]. James is very different from Lachlan. Lachlan is very solid, and James is more volatile.” As for Wendi and Rupert’s young children, Chloe and Grace, Dame Elisabeth is adamant that they not be placed in the line of succession. “I hope it never happens,” she says.

Dame Elisabeth explained she doesn’t really have much more to say about succession; it’s a topic that doesn’t come up. “I don’t discuss it with him. I’m sure he’ll never retire,” she tells me. “I don’t intend to retire either, and I’m 101.”