Tina Brown has always had a thing for older men—years ago, she’d married one. There was S. I. Newhouse, her admiring boss and patron at The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. There is Barry Diller, funding her current buzzy, money-losing Internet venture, the Daily Beast. And here she was again, on the verge of tying the knot. This time the suitor was Sidney Harman, a 92-year-old audio-equipment magnate—a young 92, he hastens to add: “I know I don’t look or act my age.” Looking for another, perhaps final act, Harman had bought Newsweek magazine for $1 (and substantial liabilities)—the deal was announced August 2—and he needed someone to run it. He’d been searching for a partner for the past four months, and now, at last, he seemed about to win over Brown, once the most glamorous and sought-after editor in the city. Brown, too, wanted a new, expanded act. And there were, or at least everyone said there were, endless synergies between the Daily Beast and Newsweek, which would merge in the deal to get Brown. The newsy Beast needed serious ballast, a big mainstream identity—about the only asset the failing Newsweek still had—while Newsweek needed to make peace with the modern digital world. But there were a couple of hitches, as there would be, given such a complicated union of companies and missions and egos.

So, a couple of months ago, Brown and Harman sat down in New York with Barry Diller, the principal owner of the Daily Beast as well as a stable of workhorse websites. For Brown, it was “awkward,” according to a person familiar with the meeting, like a daughter who suddenly discovers she has two dads. There was Harman, the warm, white-haired retired stereo magnate with the politician wife and the academic appointment, and Diller, the bald and fit swashbuckling billionaire of the old style, with a Hollywood past, a fashion-designer wife, the biggest sailing yacht in the world, and an obsessive desire for control—he dictated the look of the window shades in his beautiful, bulging Frank Gehry building on the West Side Highway.

The three pushed through the awkwardness and, over several weeks, hashed out general terms—the idea had grown from Tina’s editing Newsweek to a joint venture, 50-50, combining the youthful Beast’s editorial momentum and the established magazine’s broad reach. As recently as two weeks ago, the egos and the deal seemed to fall into place. A top adviser to Harman crowed that Diller had agreed to let Harman run the operation day to day and would take an almost parental role—“a board-level kind of seat.”

Then, the weekend before last, Harman took a hard look at Diller’s proposed governance structure. He was in his Venice, California, home, modern and seemingly Cubist-inspired, with opulent views of the Pacific and politically correct solar cells on the roof, and he didn’t like what he read.

Inside the Daily Beast, Tina and her top lieutenants had been excitedly planning how they’d run the combined business. As they saw it, they were doing a lot more for Newsweek than vice versa. “Harman gets Tina to edit Newsweek, and he gets the momentum, metabolism, and talent of the Daily Beast,” as a person close to the Beast put it. And Harman would get to chip in as many thoughts as he liked. “Sidney clearly enjoys coming up with cover ideas and story ideas,” Tina later told me.

As Harman sat studying the proposal, the joint venture started to look like a takeover. True, Harman would be a CEO-like figure with day-to-day operating responsibilities, but it seemed to him like he was being squeezed out of his own deal. Stephen Colvin, the Beast’s president, would be Newsweek’s president. And according to the proposed governance structure, Tina wouldn’t even report to Harman but to an independent board. Even if the staff at the Beast had politely kept their dismissive attitude to themselves, the proposal made their feelings abundantly clear.

“Sidney wanted a structure where he could hire and fire,” says a person close to the discussions. Harman especially wanted to have a say in guiding the content—why else would you buy into a glamour business, even for a dollar? “Tina can live with it or hit the road,” said a person close to Harman. But that was exactly the problem. Under the proposal, Harman didn’t have the power to fire Tina or Colvin. “I didn’t buy this magazine to be hands-off,” Harman told me several weeks ago.

At bottom, Harman was looking at Diller as just an investor, a moneyman, which wasn’t exactly how Diller saw it. “Barry is happy to be in business with Sidney Harman,” says the person close to the talks. “But he doesn’t want to be part of a magazine that Sidney edits.”

Then, on Sunday, October 17, as Brown sat at home watching Boardwalk Empire, her weekly “act of escapism,” she began to understand that the deal was falling apart. E-mails had shot back and forth that weekend; as one person characterized it, there was a lot of “That’s what we agreed to” and “That’s not what I agreed to.”

On Monday morning, Harman phoned Diller from California. Harman doesn’t have a permanent office at Newsweek, nor does he have a PR person or an assistant. He was making calls himself on the way to the doctor, hoping he and Diller could issue a joint gentlemanly statement. But Diller seemed fed up, and he wanted to be first to say he’d pulled out. They put out a joint statement.

Later that day, Harman was on the phone to his executives. He was grabbing a plane back to his Washington, D.C., home, and wanted to get started interviewing editors again. “Let’s go” was his attitude. “Who’s next?” He sounded almost chirpy, happy to be holding the reins all by himself again. “When I was talking to Tina Brown, I kept other candidates warm, not hot,” he told me shortly after his ten o’clock landing in D.C. “Now I will heat them up.” Two days later, he was at lunch with his next potential editorial prize, Terry McDonell, a distinguished editor, currently running Sports Illustrated Group, who, in his mid-sixties, is young enough to be Harman’s son.

A few weeks before the Daily Beast deal fell apart, Harman rushed to greet me in his airy, light-filled Washington, D.C., living room—a piece of contemporary California on the edge of Cleveland Park. He’s a small, slightly roundish, dapper man, with cloud-white hair, a terrier’s energy, and, that afternoon, unbuckled boots. He quickly led the way through his semi-wild, sculpture-dotted yard, up a set of stone stairs—within sight of a tennis court, driving range, and swimming pool, “everything a civilized gentleman needs,” as he said—and to his office, a windowed cube tucked into the woods on the edge of his property.

A 92-year-old buying Newsweek in the midst of a wrenching transition in the media business is definitionally quixotic, a noble but possibly mad adventure. “Were you in the market for a media property?” I asked him. Until a few months ago, Harman impressed friends as a contented professor, golfer, and philanthropist. He was proud of his intellectual engagement, his civic-minded projects, and his love of culture, which provided a small but rapt audience for his thoughts on the arts—“They’re mother’s milk,” he says, one of the slightly antique phrases he likes to repeat. If his name hit the news, it was because of Sidney Harman Hall, the D.C. arts center he donated $20 million to build. He had no experience in the media business, nor, as far as any of his friends knew, an interest in acquiring any. Most, without saying so, thought of Harman as a supporting character in other people’s lives, principally that of his wife, Jane Harman, a Democratic congresswoman from California. “He’s an erudite, elderly Jewish intellectual businessman,” says a person who knows him. “Charming and kind of harmless.”

To his friends, one of his talents is as a dinner host. He and Jane throw regular dinner parties for twenty or so—unostentatious affairs in their tasteful, art-filled home. The congresswoman drew the big names: Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg; Senator Susan Collins of Maine; Walter Isaacson, former editor of Time magazine and a friend of Harman’s from the Aspen Institute, where Harman is a trustee. Harman gloried in his role at the head of the table, and at the end of a meal he would stand, clear his throat, toast his “young wife,” and then recite several minutes of Shakespeare from memory, a parlor trick that never failed to impress. Then Harman would earnestly introduce the evening’s topic. “I propose this question …” Why are people alienated from politics? was one.

“It sounds kind of grim,” explains one attendee, “but it was very fun.”

In Washington, Harman had an added charm: In a town that runs on favors, he didn’t want anything from anyone, a fact that both endeared and marginalized him. “No one doesn’t like Sidney,” said a colleague, another way of saying he wasn’t really a player—in Washington, a person is defined by his enemies.

Even Jane, 65, couldn’t at first fathom her husband’s sudden desire to own a venerable but failing magazine.

“My wife, remarkable woman, was at first resistant,” Harman told me. “She said, ‘You are naïve about this city. It waits for somebody like you to pratfall and then it jumps. I’m concerned that after a lifetime during which you’ve built a sterling reputation, if this fails, they’ll be all over you.’ ”

Harman contemplated his wife’s dispiriting counsel. “Sit down, my beauty,” he told her in his courtly, formal way. “I want to tell you something. If you think I have the reputation you summarize, then it arises from the fact that I have never paid attention to my reputation. It’s not what I worry about.”

Harman resents the suggestion that at this stage of his life, he ought to do what rich older men do: caretake his reputation (and hers). As far as he’s concerned, he is still a man of action. In his business memoir, he puts it more bluntly: “People have said of me that I have balls.”

In his office, he asked me pointedly, “Do you think I’m coming to this thoughtlessly? Recklessly? I think I’m doing this with daring.” Then, dropping the stiff public-speaker manner, he added, “The vast majority of people get up figuring out how to get through the goddamned day. I say, ‘Take charge of your own damned life.’ That’s what I’m doing with Newsweek.”

Harman’s remarkable late-life self-actualization was triggered in May, when the WashingtonPost Company’s board, of which Diller is a member, decided that Newsweek was unlikely to snap out of its funk anytime soon. The magazine has been unprofitable since 2006, and the company already has one money-loser on its hands, the storied Washington Post. To Harman, news of the sale was like an epiphany. One person later described his interest as an “enormous quest for relevance.” Harman viewed it as a logical next step, a capstone to his career, tying together his interest in education, government, and business. “I’ve been preparing for this for nearly a century,” he explained to me.

That he might be out of his depth in the media world didn’t faze him. He prides himself on his nimble brain—his exasperated first wife told him his “think switch” is always on—and a drive to succeed so fierce he thought it beyond his control. “I am puzzled to this day what it was that drove me,” noted Harman about early periods in his life. Clearly, one thing that drove him was his upbringing. Harman was raised in a New York City of blessed memory, of ethnics and egg creams and candy stores and, for a budding entrepreneur, business opportunities—he sold discarded magazines picked up on his paper route at those candy stores. It was, in his recollection, an idyllic childhood, except for one thing. “My father was a piece of work,” he told me with emotion. He was a tiny, “physically potent” man and, in Harman’s memory, a profound narcissist who sucked up the family’s emotional energy. “I decided as a kid I was going to be very different from my father,” he told me. “Early on, I took him on,” not physically but in every other way. “Curiously, he was in a sense in the audio business,” Harman explained. His father was in the hearing-aid business.

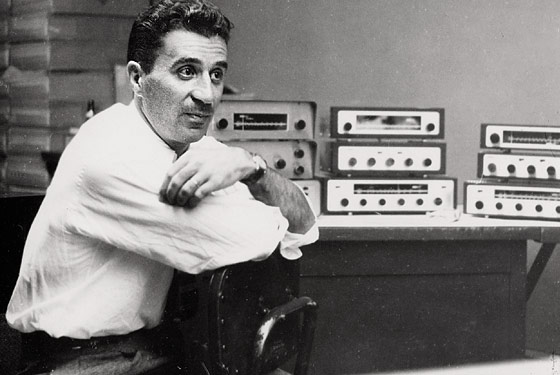

Out of City College, Harman joined the David Bogen Company, an electronics firm that sold PA systems, climbing rapidly until the owner refused to innovate; then he and a colleague, Bernard Kardon, left to form their own company with $10,000. Kardon was the lead engineer. “I’m the resident visionary,” Harman wrote in his memoir. In the fifties, he recognized that a newly prosperous postwar consumer, intrigued by technology, drawn to design, and prepared to pay for quality, was hungry for a better experience of music. Harman-Kardon pioneered high-end stereos for the home and succeeded phenomenally—twice. In 1977, Harman—by then Kardon had retired—sold the company to the conglomerate Beatrice Foods; then in 1980, after Beatrice drove it into the ground, he bought most of it back at a bargain price, rebuilt it, and in 1986, took Harman International public.

Business success both delighted and deflated Harman. On one hand, he could champion cherished causes—he funds the Shakespeare Theatre Company in D.C. And yet business didn’t fulfill other desires: Harman wanted to be taken seriously as a man of intellect and sensitivity, one with, as he puts it, “a growing [social] consciousness.” In the seventies, he earned a doctorate in social psychology. “I had long felt guilty in my role as businessman,” he wrote. Jane was elected to Congress in 1992, and their immersion in the capital’s culture made his discomfort more acute. “I’d go to a dinner party in Washington, and somehow I’d always be seated next to the oldest, ugliest woman at the party,” Harman told me. “She’d inevitably ask what I do. If I said I’m in business, I’d get one of those searching looks. So I’d make jokes. I’m a golf pro. I play the piano in a house of ill repute.”

In his office in the woods, Harman was determined to convince me that business is just one side of a multifaceted and broad-gauge career. He marched me through a history of his notable, if underappreciated, achievements beyond the business world—I could barely get a word in edgewise.

In the Kennedy era, he taught black kids shut out of a Virginia public education system—his car was trailed and bumped, a frightening, exhilarating experience. In 1970, he signed on as president of Friends World College, a small, experimental Quaker college on Long Island, where he lived at the time. “I would get to the [Harman] office before seven in the morning and work until one, a full day, no interruption, then I’d drive myself 40 minutes to campus, eat lunch in the car, change to jeans in the car … and work until midnight, seven days a week,” a schedule that helped end his first marriage. In 1974, at a Harman factory in Tennessee, he spearheaded a kind of utopian experiment, giving employees power to run their work lives. “The first time in American industrial history a serious effort to alter the traditional adversarial relationship between the managed and the management,” Harman explained to me, in case I’d missed the significance. The project led to his appointment as undersecretary of Commerce in the Carter administration, where, he said, “I did innovative stuff.”

In 2008, Harman joined the faculty of the University of Southern California, where he is a “sizable” donor—he finally retired from Harman International Industries in 2008, at age 89. He’s long been a voracious reader, interested in how great thinkers think. At USC, he explained, “I’m developing a totally new college” under the aegis of the Academy of Polymathic Study, which, though it won’t offer college credit, will produce a series of provocative seminars. The Academy is “no … small … damned … thing,” he explained, pausing dramatically between words.

As soon as he heard of the Newsweek sale, Harman phoned the magazine’s longtime writer Howard Fineman, an old friend who happened to have covered Jane’s failed bid for governor of California—a campaign Harman helped finance. Harman invited Fineman to lunch at the Hay-Adams Hotel, where the health-conscious nonagenarian ate a salad with mushrooms and listened intently. Fineman saw himself as explainer, not salesman. “Newsweek is a great brand, damaged but great,” Fineman began. It has a global reach, which few news organizations still do. Fineman thinks of Harman as “a great citizen, a super-citizen.” Newsweek is a home for great reporting, which, Fineman explained, “is worth saving.”

The deal fell apart over control. “I didn’t buy this magazine to be hands-off,” Harman says.

Newsweek, too, viewed its editorial talent as its “core asset,” and its offering memo mentioned them by name: writers Fineman, Evan Thomas, and Fareed Zakaria, among others. At the Hay-Adams, Harman talked enthusiastically about keeping together the “band of brothers,” as he called the writers and editors, referencing the famous St. Crispin’s Day speech in Henry V, a passage that Harman could recite from memory.

Harman proved a canny suitor, strategically deploying his avuncular persona. In June, two months before the winning bid was announced, Harman was already telling people he’d locked up the deal. “He’d gamed it,” says a person who spoke to him at the time. Donald Graham, a principal owner of the Washington Post Company, acknowledged the financial necessity of the sale but told me, “I was very, very attached to Newsweek.” He is still overweeningly proud of the company’s heralded journalistic tradition, even as it is kept financially afloat by its test-prep service, Kaplan, as well as its cable company. Graham believed he was passing along a cherished family possession.

“Sidney had figured Don out,” says the person who spoke to Harman at the time. “It was very shrewd.”

The two other finalists, Marc Lasry at hedge fund Avenue Capital Group and Fred Drasner, offered deeper media experience—Avenue Capital is an investor in American Media, and Drasner, former publisher of the Daily News, recruited Alan Webber, co-founder of Fast Company, and Paul Ingrassia, formerly of The Wall Street Journal, to his side. But the teams rubbed some Newsweek management the wrong way. During conference-room presentations, Drasner in particular struck some as pompous.

By contrast, Harman was unassuming,similar in presentation to the 65-year-old Don Graham, which opened doors. “Sidney was given access in a different way,” explained Tom Ascheim, Newsweek’s CEO, who acted as Graham’s agent. Ascheim met with Harman in his homes in Washington and California. “It was just the two of us,” said Ascheim. “It was familial in its own odd way.” Harman didn’t propose cost-saving synergies—he had none to offer. Like everyone else, he would have to cut staff, from about 350 to 250, he said, but Harman assuaged Graham’s guilt over Newsweek’s mismanagement. “I will care seriously about the people, not as spare parts of the machinery, not as inventory, but as fundamental and consequential,” he told Graham. “I’m in this to have a helluva good time, a constructive good time, for myself, the staff, and readers.” Still, his most compelling qualification was probably that he was willing to lose tens of millions of dollars on Newsweek. “I’m not in this to make money,” Harman made clear, another bond with Don Graham.

Run for Cover

And so, months before the winner was announced, Harman was acting as owner, suggesting ideas for cover stories—how about one on creativity? Steven Pinker could write it—stepping into the role of Newsweek’s new father figure, one for which he’s sure life has prepared him. “It’s the culmination of everything I’ve done,” he explained to me, which, in a leap of logic, he believes qualifies him to lead the magazine. “Do I have doubt about whether I can be the guide, the inspiration for the reinvention of Newsweek?” he asked me. “I’ve spent the last 40 minutes making the case that I’m the guy, if not uniquely equipped, damned well equipped.”

His first task was to recruit an editor, and in June, he set his sights on columnist Fareed Zakaria. An Indian-born Muslim educated at Yale and Harvard, Zakaria is perfectly positioned to explain a threatening world to the increasingly insecure Sunday-morning talk-show set. Moreover, he was one of “the big boys,” as Harman sometimes calls movers and shakers—an intellectual celebrity who glides through the media-power circles where sources, friends, and fixers are one and the same.

Zakaria was the magazine’s franchise player, and Harman shared his vision for the magazine with him. “What is Newsweek’s appropriate mission? Clearly it’s not to tell you what happened in Greece or Indiana. The opportunity for Newsweek is to weekly make sense of it all. To connect the dots: There’s a phrase that resonates not just for the American public but for world,” was the way he explained it to me. (He wants to trademark the phrase “Connect the dots.”) Zakaria wasn’t swayed. Harman was restating the obvious—the old Newsweek also aspired to connect the dots—and was thinking out loud as to how to fix a broken Internet business.

Zakaria, though, didn’t immediately turn Harman down—which nicely served the Graham family, who didn’t want a key asset off the table. But as Zakaria considered the offer, Newsweek’s situation was deteriorating. It turned out the band of brothers had divided loyalties and practical heads. They had to make a living, and no one knew if Newsweek had a viable future. The magazine became a poacher’s paradise. Twenty-three name-brand editorial employees have left since June, by one recent count. Fineman was among the prominent departures, taking a job at the HuffingtonPost, along with columnist Evan Thomas and investigative reporter Michael Isikoff.

In mid-August, a couple of weeks after theWashingtonPostCompanygave Newsweek to Harman for $1, Zakaria finally told him he wasn’t interested. “I thought Sidney was delightful,” Zakaria explained to me, “but I wanted to write and do my TV show. I’d run Newsweek International for ten years. I didn’t want to be an editor in a period when the business model is collapsing and I would have to focus my energies on a turnaround.” Zakaria’s first loyalty is to his own brand, now considerably more robust than Newsweek’s. Since 2008, he’s had his own Sunday-morning TV show on CNN, part of Time Warner, parent of Time magazine. He signed on as a columnist for Time, which, among other advantages, is financially healthy.

Zakaria agreed to do Harman one favor; he wouldn’t mention the editorship offer, according to a source close to Harman, permitting Harman to put a positive spin on the high-profile defection. “Fareed has done us a great favor by leaving,” he told people inside Newsweek, “so we can start fresh,” though he insisted on holding Zakaria to his contract and not a single column less. Harman soon began to talk about the excitement of finding a new generation of talent. “He is constitutionally incapable of disappointment. He reimagines reality to be what he wants it to be,” explained a person who has worked with Harman. “He reframes the moment as the best of times. It’s probably a key to his success.”

Harman even seemed to enjoy the delay, delighting in the press’s fervor to know his every thought. Reporters now ask Jane about him—turnabout, at long last.

Fineman had cautioned Harman, “Don’t buy Newsweek and then figure out what to do with it later.” Have a plan. “Sidney said, ‘That’s wrong.’ ” He’d figure something out once he owned it. He thought back to his days of entrepreneurship; he’d always been able to solve problems on the fly.

“You’ve never had a setback,” I mentioned in his office.

“Not yet,” he answered sheepishly.

Harman had negotiated hard with the Washington Post Company. He paid $1—a sixth of the price of a single copy—and assumed liabilities of $47 million, mostly in unfulfilled subscriptions, which isn’t money out of his pocket. His up-front investment is $25 million in working capital; the Washington Post Company kicked in another $20 million. With cost cuts—there was another round of layoffs on September 24—Newsweek might lose less than $15 million next year, according to projections. And it will likely lose millions this quarter, which is Harman’s responsibility; he will almost certainly have to put in more money, perhaps a lot more. Not that he cares. “It’s an amount I can afford to blow,” he says. (Forbes estimates his fortune at about $500 million.) More important than money, the project invigorates him, one reason he seems to drive it all by himself, shuttling from coast to coast, phoning executives from his homes, his operational headquarters. “Why in the world would I invest, engage in something like this, and be hands-off?” he asks me.

Harmonizing Harman

Photographs: From Left, Brendan Smialowski/Getty images; Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty images; Newscom (2)

In Harman’s office, the tour through his underappreciated past had ended. The room was momentarily quiet. Harman looks great, perhaps twenty years younger than he is; he exercises daily—he recommends “crunches” to the many who ask. Harman long ago learned to defuse questions about his age with humor—he bought Newsweek to put an end to a misspent youth, he quipped. Still, the subject is unavoidable, and so I asked if the actuarial tables ever sadden him. The question annoyed him. “I know damned well I don’t have the affect of 92 years,” he said, waving off the subject, “the way I move, the way I act, the way I talk.”

A key to his vigor are genes—his mother lived to 98—but another is Newsweek. “It keeps me alive and curious,” he told me, another step in his life’s journey. “It permits me to experience a more expanded, integrated, synthesized life.” With a vision like that, who needs Tina Brown?

Harman pulled a cell phone out of his pocket and arranged a taxi for me, politely but firmly ushering me out. He had work to do.

“Some might say Newsweek is a … What’s the word that always escapes me? What’s the word for the extinct animal, the giant Laplatasaurus?”

“Dinosaur?” I said.

“Why can’t I remember the word dinosaur?”

Then he was off again, leading me through the sculpture garden, talking about Newsweek’s glorious future, and his own.