OHHH MY GOD—A BIG JIANT SPIDER JUST CRAWLED ON MY PILLOW!!!!!! ARGHHHH OMG OMG OMG EWWWW OMG!!!!!!!!!!!

The tweet from Meghan McCain, the 27-year-old daughter of the senator from Arizona, bounces through a wireless network and pings around a maze of servers until it lands inside a batch of computers situated on the third floor of a seventies-era office building in San Francisco, corner of Folsom and 4th Street.

At the headquarters of Twitter, there is an open-air hive of cubicles and a large, light-filled common area where staffers in T-shirts and jeans congregate with matching silver MacBooks with bluebird logos on them. There is a five-tier cereal dispenser and several varieties of boutique coffee; communal dishes are piled in a sink. On a marker board near the exit, employees share their ideas for making the company more humane, writing “flexible” and “artful” and “be polite.”

All is not transparent, however. Floor three, the technological core of this unusual enterprise, is off-limits. A sign tells those with access to WATCH FOR TAILGATING. Behind the double doors, computer engineers, some 250 of them, Ph.D.’s from MIT and Stanford and Caltech, are busy trying to make order of the 200 million tweets a day, cascades of text messages from McCain, President Obama, and the pope; Justin Bieber and the Pakistani who heard U.S. commandos raid Osama bin Laden’s house; Kanye West and Hugo Chávez and the man who pretends to be Nick Nolte all day. Back there, in an attempt to solve the inherent paradoxes at the core of Twitter’s ambitions, computer algorithms are being developed to classify and assign values to every single tweet in the ever-chattering Rube Goldberg machine they created five years ago.

At Twitter, they like to measure human events in tweets per second, or TPS. The more tweets per second, the more impressive and important the event—Twitter as the most important measure of human history. The company started releasing this number the summer of 2009, when Michael Jackson died and crashed Twitter’s service under the weight of 493 TPS.

On computer monitors on floor three, they can watch TPS for an event spike like commodities on a trading desk. The freak earthquake in Virginia in August reached 5,500 TPS, a number released to the press as a significant barometer of impact: “More tweets than Osama bin Laden,” said the London Telegraph.

That compares to 5,530 TPS for the Japanese earthquake and tsunami. Or 6,436 TPS for the 2011 BET Awards, and 5,531 for the NBA Finals. In August, the new Twitter record was set: 8,868 TPS for Beyoncé’s performance at the MTV Video Music Awards.

“People describe Twitter as a global consciousness,” says Ryan Sarver, a fast-talking engineer who comes out of his third-floor sanctum to meet me in a conference room. Sarver, who is responsible for managing this chaotic flow, the so-called fire hose of tweets, says Twitter has only begun to take shape. “We’re in the early life cycle of what the platform is,” he says. “This is version one.”

In Silicon Valley, Twitter is already legend, one of those once-a-decade sure things, on the level of Microsoft or Apple or Google or Facebook—that not only changes the nature of the world but eventually makes it hard to remember a world in which it didn’t exist. The ambition, and some of the rhetoric, is Gutenberg-size, though instead of Bibles, there’s Beyoncé.

“There are nearly 7 billion people on this planet,” says Jack Dorsey, the company’s co-founder and original genius. “And we are building Twitter for all of them. They evolve, and so do we.”

Measured by the number of people who’ve joined the flock, Twitter’s growth is indeed staggering—a 370 percent surge in users since 2009. In fact, it resembles nothing so much as Google a decade ago, and everyone here, along with the small army of venture capitalists whose millions are funding this laboratory, is aware of this fact, as well as the implied competition with social-media superstars like Facebook and Zynga that are promising to go public and make lots of Valley V.C.’s very rich. Google has launched an assault with Google+, a more controlled social world, equidistant from Facebook and Twitter, and thus a possible refuge for those who are disaffected by Twitter’s chaotic news flow.

The intense pressure to convert Twitter into a profitable business, and before a tech bubble pops, is palpable here. And it’s happening as the company struggles with an interlocked set of existential questions, starting with the most basic one possible: What is Twitter? Initially, the idea was of a kind of adrenalized Facebook, with friends communicating with friends in short bursts—and indeed, Facebook rushed to borrow Twitter’s innovations so it wouldn’t be left behind. But as Twitter grew, it finally became clear to Twitter’s brain trust that the relevant analogy was not a social network but a broadcast system—the birth of a different sort of TV.

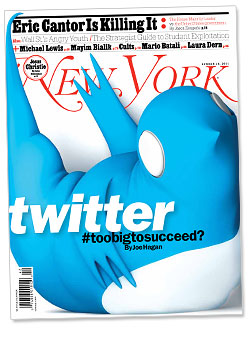

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

They call it an “information network.” “It did take a while to bring everybody around to that particular vision,” says Twitter co-founder Ev Williams. “Over the last year or so is when that started to be more clear publicly.”

But this revelation both simplified and complicated things. Where Facebook could keep aiming to be a comfortable place for people to hang out, Twitter’s job would be to broker a connection between an audience and the talent, while also paneling itself with lucrative advertising, unobtrusively enough that the audience would not tune out. And currently, neither audience nor talent nor, especially, advertisers are anywhere near where they need to be for Twitter to make good on the immense expectations under which it is laboring.

At Twitter, where anxiety and optimism are never far from one another, the leadership is surprisingly frank about these problems. To start with, the audience is alarmingly fickle. Nielsen estimated that user-retention rates were around 40 percent. Twitter was easy to use at an entry level, but after a while it was hard for some people to see the point. Twitter has claimed as many as 175 million registered users, but numbers leaked to the online news site Business Insider in March put the number of actual people using it closer to 50 million, correcting for dead and duplicate accounts, automated “bots” and spam.

“There’s this big gap, no doubt about it, between awareness of Twitter and engaged on Twitter,” says Dick Costolo, Twitter’s CEO, a former improv comedian whose bald head and square-framed glasses give him the look of a walking exclamation point. When I meet him, he comes dashing into a corner office, apologizing for having initially canceled our interview as the company raced to process a new round of financing, $400 million from the Russian billionaire and highly regarded venture capitalist Yuri Milner—more money, more pressure. Costolo, along with Dorsey, who was pushed out two years ago and then returned, Steve Jobs–like, to try to take the company to the next level, are in charge of keeping the people in their seats. “This is probably our biggest product challenge, and the thing that Jack and I talk about the most,” says Costolo.

The problem starts, he says, with an empty box. The box is on a user’s Twitter home page, where the company’s signature timeline is supposed to crawl down, overflowing with 140-character bon mots, witty and interesting and profound. But when you sign up, there’s nothing in it. It’s like turning on the TV and being confronted with a test signal.

“You sign up for Twitter, you see the empty timeline and a big ‘What’s happening?’ at the top,” Costolo tells me. “We need to bridge that gap between you sign up for Twitter and you’re staring at the white space and what do I do now?”

This by itself should not be a hard problem to solve. But by solving it—gaining, or holding on to, users—Twitter will create the next big problem. Add a quantum leap in loquacious tweeters, and what you have is an unmanageable flow of tweets, only a few of which are of any interest—the rest of them so much cultural detritus floating by in the flood.

As it stands, Twitter’s interface has yet to mature beyond a chronology of tweets, from most recent to oldest, that necessarily drops people into the water without much context, forcing users to experience Twitter as a snapshot of comments and a somewhat random and not particularly useful list of “trending topics,” or to enter a search term in hopes that something pertinent or entertaining will emerge from the millions of tweets. “In general, a lot of what Twitter is is unstructured information,” an executive at Facebook tells me. This, in a sense, is a programming challenge.

Costolo, of course, phrases this critique in much more optimistic terms. “There’s this huge opportunity for us to surface all this great content,” he says, “and to allow people to discover what’s going on on Twitter.”

“Surfacing the content”—essentially, curating tweets for users—is a phrase you hear a lot at Twitter. It’s the solution to both the problem of the empty box and the opposite problem, the cluttered stream. It’s the project that Costolo and Dorsey, along with their third-floor computer wizards, are obsessively consumed with: matching Meghan McCain’s arachnophobic tweet with that subgroup of political junkies and spider enthusiasts who might want to read it.

This summer, Twitter reengineered its search engine so it would value the “influence” of its users to better organize search results—to automatically bring up what Brian Williams and Wolf Blitzer said about Libya as opposed to what somebody’s crackpot uncle or Richard Simmons said. Already, Twitter has tried to use interest-based “lists” to funnel people into thematic silos, an attempt to improve on the relatively primitive hashtag, the ubiquitous symbol for organizing ideas on Twitter. But unlike a news or social site, where authors and their data are clearly delineated, the Twitter experience is much more difficult to aggregate.

“At a simplistic level, it sounds easy,” says Costolo, “because we could just go find, you know, the top trending topics and the tweet that was retweeted the most in the last two hours and show people that. But you want to be able to surface discovery at the global scale—‘Hey, there’s fomenting revolution in Tunisia’—but also surface discovery at the hyperlocal level: ‘I can tell by the fact that you’re on your iPhone, and you’ve exposed your lat-long [your location, as latitude and longitude] to me that you’re at the Giants game, and here are a bunch of other tweets and pictures people are tweeting from the game right now.’ ”

The danger of overstructuring the information, he says, is that the user stops experiencing Twitter the way people originally came to experience Twitter, as the place for free-form, serendipitous chatter.

“You lose the roar of the crowd,” says Costolo. “You look at the search results and ‘Oh, there was a goal,’ but you lose the athletes you follow and Mario Batali and Dennis Crowley from FourSquare. It’s a design and engineering challenge.

“This will be built into Twitter,” he promises, “as a way of reducing the distance between awareness and engagement.”

As it happens, that’s the exact distance between Twitter as a phenomenon you’ve heard of and Twitter as a huge moneymaking business.

But to surface the content, and keep the audience happy, you have to make sure that the content keeps flowing in, and this, too, is far from a sure thing. A study conducted by sociologists working for Yahoo found that if they looked at a random Twitter user’s feed, roughly 50 percent of the tweets came from one of just 20,000 users.* “It’s really dominated by this media-celebrity-blogger elite,” says Duncan Watts, one of the researchers. “It’s a small number of users who are hyperconnected, and then there’s everybody else just paying attention to those people.”

“They have a TV-radio problem—how do you monetize TV? No one remembers who the first CEO of radio or TV was.”

To continue the broadcast metaphor, these people are the show users came to see. And Twitter is learning that it has to tend the talent as carefully as any entertainment company. In the planning rooms of Twitter, the most prolific and widely followed tweeters are called “influencers,” or “power users,” and they are at the core of its business. If it loses them, it becomes, essentially, MySpace—a digital graveyard where a party used to be. So while they race to retool the tweeting experience for the masses, Costolo and Dorsey are on a parallel campaign to keep Twitter’s star attractions, celebrities and politicians and the media, chattering away on Twitter. Last year, they opened offices in Hollywood and Washington, D.C., hiring liaisons to act as free Twitter consultants and keep influencers pumping out all-star tweets. In a conference room around the corner from Costolo’s office, Omid Ashtari, a former agent at Los Angeles talent firm Creative Artists Agency, tells me the pitch he gave actor James Franco before the Oscars last spring: “If you’re on Twitter and you have a spotlight shining on you in other media, your Twitter resonance and your Twitter growth explodes.”

The reason Twitter wants James Franco tweeting is to sell his audience to advertisers. And if it can figure out how to insert a Starbucks tweet into the Francosphere, and prompt people to buy coffee without stifling their intimacy with Franco, Twitter wins. This advertising model is still in the dream stage. But what a dream it is.

“A new kind of advertising that can go everywhere, frictionlessly, immediately,” says Costolo. “It’s not just a browser ad, it’s not just a desktop ad, it goes to smart phones, it goes to feature phones, it can go to SMS [text messages], it can go to TV.”

In theory, it’s an ad-sponsored tweet that would go everywhere you want to be, cozied up with your friend James Franco like Texaco was with Milton Berle 60 years ago.

But while they’re doing all this blue-sky dreaming, the noise outside their windows is getting very loud. And Twitter is still recovering from self-inflicted wounds: The founders and early funders fought a pitched battle for months over what the company should be and who should run it. As one venture capitalist in Silicon Valley observes, it looked like the founders “drove their clown car into a gold mine and fell in.”

Dorsey, a young engineer who came up with the idea of Twitter and helped build the prototype, was pushed out three years ago in a feud with co-founder Williams, its first funder and chairman, just as Twitter was becoming popular. The board of directors made Williams the leader, but after two years, Williams stepped down, evidently overwhelmed by the job. The board then handed the reins to Costolo, who had been advising Williams, and, in a bizarre about-face, brought Dorsey back six months ago as the new front man and chief product manager. Williams and a third co-founder, Biz Stone, who are still board members, decamped to start a new venture.

*This article has been clarified to show that Yahoo’s research findings were in reference to single Twitter accounts, not all users, and that they did not find that 50% of all tweets originated with those 20,000 users.

It’s all happening a little too fast. “We’ve certainly resonated with a lot of people,” says Dorsey. “But does that mean that we’ve arrived and can never go down? Absolutely not.”

“All right, I’m ready to Tweet!”

It’s the president of the United States, clapping his hands and walking down a hallway in the White House. A group of Twitter staffers receive him in the green room outside the West Wing, where he’s about to star in the first-ever Twitter Town Hall. He will answer questions from people who tweet. They give Obama a T-shirt; he thanks them and marches out to a podium with a laptop on it, a wan George Washington looking on from an oil portrait behind him.

“I’m going to make history here as the first president to live tweet,” Obama pronounces. He straightens up and types while a bank of cameras clicks. Obama hits return, and the presidential tweet, in which he asks for suggestions on how to reduce the deficit, is posted. When it appears on a screen behind him, Obama looks, smiles, and says, “How about that?” And so it is: The leader of the free world in an infomercial for a San Francisco technology company. As pure theater, it feels like an exhibit from the 1939 World’s Fair.THE TALKING MACHINE OF TOMORROW! As Ezra Klein of the Washington Post tweeted that day, “Our next question comes from @twitter: ‘Isn’t Twitter awesome? Is this your favorite Townhall ever?’ ”

This event was the apex of a campaign that began the year before, when Twitter hired Adam Sharp, a former aide to Senator Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, to promote Twitter among the political class, helping to “authenticate” the Twitter feeds of government officials against impostors and parodies, giving them a blue “check” next to their Twitter handle, and “onboarding” as many new officials as possible. The wooing of the president began with a series of Twitter Q&A’s with Robert Gibbs, the former White House press spokesman, after which Sharp began negotiations.

When it first exploded in the popular culture, Twitter was used by celebrities and sports figures like Ashton Kutcher and Shaquille O’Neal, as well as the early adopters and techno-utopians who gave it a kind of world-changing halo. And quickly, Twitter did seem to help change the world, first in Iran and then in the chain of rebellions of the Arab Spring. Just how significant Twitter’s role was in catalyzing these events is still the subject of heated debate. But it certainly helped to catalyze the media’s coverage while simultaneously providing an irresistible metastory: American technology is changing the world for the better.

And just as Google capitalized on its “Don’t be evil” slogan, advancing human freedom became part of Twitter’s business model. The company and its founders were lauded on the covers of Time and BusinessWeek and celebrated by the U.S. government as merchants of goodwill. In 2009, Dorsey was invited on a State Department–sponsored tour of Baghdad, part of a delegation of high-tech executives. An early investor, venture capitalist and former Google executive Chris Sacca, held court at an exclusive New Age retreat in California last summer to talk about “The Yoga of Twitter.” “We decided we needed to be an affirmative force for good,” he explained. “Our fifteenth hire was a corporate-social-responsibility person. In fact, as an investor, it used to drive me crazy. We’ve got stuff to build! We’re too busy helping people!”

But at the core of all this world-historic buzz, there was an emptiness. Early this year, reports began surfacing that Twitter’s growth was flatlining. Twitter now says it has 100 million “active” users, though only half are people who log in to see their timeline with any regularity.

To attract and hold the audience, and to attract the talent, Twitter needs the media as its accomplice. In 2008, Twitter hired Chloe Sladden, a former executive at Al Gore’s TV network, Current, to work with news agencies and cable networks. An attractive and animated speed-talker with bright, flashing eyes, Sladden was tasked with convincing old media that Twitter was the handmaiden to their future.

“We’re in this together,” she recounts telling reporters in New York newsrooms, offering herself as “psychological support” to the new-media people who needed hand-holding or faced skeptical management. On Election Night in 2008, Sladden says, she acted as a standby consultant to the New York Times and CNN. “We spent from 8 to 11 with the Times and then CNN from 11 to 3 a.m.,” she recounts. “We tried very hard to be with our partners when it mattered most.”

She also acted as talent scout. After meeting the Times media columnist David Carr at the Austin technology conference South by Southwest, Sladden gave him a spot on the company’s sign-up page among its suggested users, pumping his follower numbers up into the hundreds of thousands. Carr, playing to his enormous audience, tweeted obsessively, day and night, about everything from his vacations to his dinner, and he wrote about Twitter in his column too, opining on its “practical magic.”

The impact of all this hand-holding was not only to help the media but also to help the media help Twitter. To make Twitter seem inevitable, it got people with large organic followings, like newspeople and celebrities, to use it and draw in more users—what social-media investors call “viral looping.” Fred Wilson, an early Twitter investor and until recently a board member, has joked that his company, Union Square Ventures, could be renamed “Viral Ventures.” Companies like his often track progress using a number called the “viral coefficient,” a measurement of how well the brand is being amplified by its own users.

Sladden is in charge of schooling these crucial adoptees—TV talking heads, reality-TV producers, newspaper columnists—in the ways of Twitter, which is, in essence, about giving followers that “magical feeling” of being inside with the insiders. Sladden’s message is that to build an audience, you have to draw back the curtain on your life, or appear to. (Anthony Weiner may have taken this too much to heart.) In Sladden’s view, this is perfectly in step with broader developments in the culture. “We’re changing to this more quote-unquote authentic media experience,” she says, “and everything is caught on tape. And that was a big part of the mission here, making it a two-way experience.”

The key to this quote-unquote authenticity (this, after all, is the age of the oh-so-authentic Kardashians) is the use of the word I. The first rule of Twitter is that talking about yourself makes the tool work better. The upshot is a narcissism so democratized that users don’t have to feel guilty about it and, in fact, barely notice it.

Out in Hollywood, Omid Ashtari has telegraphed the same “authenticity” message. He spent several weeks this summer persuading Justin Timberlake to do a Twitter Q&A to promote a movie, which made the thematic hashtag #askjt the No. 1 Twitter topic in the world. “You’ve just got to be authentic; that’s how you grow your follower base,” Ashtari says. “Engagement and authenticity will lead to a stronger audience, and that’s pretty much what I preach.”

Working closely with new-media staffers in the congressional caucuses, Sharp held private events to teach senators and congresspeople why and how they should use Twitter, promising that they can “build a deep echo chamber to have a continuing dialogue with these people, who then go into their communities and they can say, ‘I was tweeting with Senator So-and-so last night.’ ”

Sharp figures three-quarters of Congress has signed on to Twitter. Says Sharp, “If they can make that connection—‘Oh, he’s a family man, he’s just like me,’ or ‘She’s a working mother, just like me’—the candidates realize that the ‘just like me’ is the most effective foundation for engaging to the political conversation.”

Journalists and bloggers, too, have learned that they attract more followers by “making the connection.” “It’s like voguing,” observes Andrew Breitbart, the conservative blogger and stunt rabble-rouser who frequently engages in Twitter flame wars with liberal adversaries. “Getting onstage and acting like a model. Everybody has their inner model and inner exhibitionist they want to get out there. I’m just one of the millions.”

Brian Stelter, the TV and media reporter for the New York Times, has adroitly mixed news reportage with details of his personal life, tweeting links to his stories along with documentation of his efforts to lose weight and updates on his onetime love affair with a CNBC reporter named Nicole Lapin. When the Times ran a story on its front page about TV cable boxes draining power from people’s homes, Stelter tweeted to his girlfriend, “I watch your show even though it drains my cable box AND my body clock. #goodboyfriend.”

He has embraced the Twitter credo: The more personal information you reveal, the better. “The tweets with the word I in them tend to be really well received, and the most retweeted,” he says. While this is all amusing, it also encourages a kind of elitism, an unintended consequence of a supposedly democratic medium. “It’s where the inside conversation is happening right now,” says Ben Smith, a reporter for Politico who tweets dozens of times a day. But, he says, he notices how it exaggerates the insular, lemminglike effect already prevalent in the media. “It requires you to play within the consensus,” he says. “If you’re not buying the premise of the conversation, you’re not really welcome in a way.”

Stelter, lauded among his peers as the future of tweeting journalism, says he can’t imagine life without Twitter. “I want to live in that stream,” he says. “So scary to hear myself say, ‘I can’t imagine life without it.’ It’s a private, for-profit company.”

Well, not for-profit yet. Which explains the undercurrent of dysfunction and anxiety at Twitter. Consider the conversation I overheard on the elevator between two engineers exiting to the third floor.

“Did you read the e-mails last week?

“Yeah. A lot of changes.”

They sighed, shrugged.

“It’s to be expected, I guess.”

The week before, four senior product managers, top engineers, had left the company. And within a month, three more would depart. A person with close ties to the company says the morale inside Twitter, especially on floor three, has been low. In the hothouse of Silicon Valley, engineers are the coin of the realm, and what they want, in addition to a financial stake, is to put their stamp on a winning company, even if it means working for one of the thousands of tiny startups developing applications for Facebook or Google. Twitter, while sorting out its strategy and management problems, has hired hundreds of new engineers, even as it’s taken its sweet time rolling out new features those engineers can lay claim to.

Everyone involved knows how tenuous Twitter’s footing may be. “We’re a fraction of the way into creating the value and growing the size of the service we know it can be,” says Williams. “It’s precarious, and it’s always precarious when you’re in that position.”

Based on speculative secondary markets for private shares sold by former employees, the company is currently valued at $8 billion. But with more than 650 employees to support, and income projections for this year well below $200 million, it’s not yet clear how it gets from here to there. In August, the company raised another $400 million and used it to buy out early investors, a sign that some money is already being taken off the table.

“They’ve got ahead of themselves in their private valuations in the secondary market,” says John Battelle, a technology journalist who heads high-tech marketing company Federated Media and is a friend and neighbor of Costolo’s in Marin County, north of San Francisco. Perception of Twitter in the Valley is that it’s fragile. One Twitter investor who has not yet cashed out told me, “There’s a lot of head-scratching. They look at Twitter’s numbers, and they say, ‘That’s all they can do with that?’ ”

“The criticisms of the company are very loud,” acknowledges Fred Wilson. “A lot of people don’t take the time to understand Twitter for what it really is.”

Unfortunately, what it still is is a gold mine without, as yet, any sure way of getting the gold. And if too much dreck pours in, in the way of self-promoting tweets and obtrusive advertising, the gold may be lost forever. For Twitter, it’s a hazardous paradox. As Ashton Kutcher recently said, “There’s a danger of it becoming spammy, and that’s what really hurt MySpace … If Twitter doesn’t apply the proper filters, it’ll be harder to find the information you want. With Facebook, I’m probably not going to get spammed from my aunt or my best friend.”

What’s great about Twitter, as opposed to its competitors Google+ and Facebook, is that it’s a free-for-all, with few rules, welcoming anyone and anything—it can be unpredictable and wild. But the danger is the Wild West becomes so many digital strip malls. And who’d want to spend time there?

Twitter, distracted by technology problems and infighting among its founders, was practically the last to understand that curation and filtering is part of its business. At first, it was happy to let users, and start-up developers, take care of it. One of the early attempts to focus Twitter was StockTwits, co-founded by an angel investor named Howard Lindzon. He used the symbol of two dollar signs, $$, as a code that users could add to their tweets, allowing Lindzon to sift for $$-related tweets and invent a separate conversation band for traders and businesspeople. “Curation and discovery is everything,” says Lindzon. “Otherwise it’s the dumbest product you’ve ever seen in your life.”

Consequently, Lindzon has managed to peel away a whole thread of valuable conversation from Twitter. And he wasn’t the only one: TweetDeck, a popular platform for monitoring Twitter, marshaled Twitter’s users into its interface and was on its way to selling ads—until Twitter realized this was its business and paid $40 million to acquire TweetDeck in May. People like Lindzon, whose company is built on Twitter, believe Twitter is an invention akin to TV, an amazing development, but not worth anything without defined channels like his. “They have a TV-radio problem,” says Lindzon. “How do you monetize TV? Nobody remembers who the first CEO of radio or TV was.”

Nicole Polizzi, A.K.A. @Sn00ki: “When your ass and chest is on fire cuz you used too much tingle in the tanning bed #GuiDeTTeProblems !!!”

This is the power and the greatest weakness of Twitter: the irresistible urge to advertise oneself. The impulse to make life a publicly annotated experience has blurred the distinction between advertising and self-expression, marketing and identity. Everyone is a celebrity, in the same stream. Marketers, too. And behind the scenes, advertisers are using an interface you’re unlikely to see: a “dashboard” for watching you watch them, the online back room where Volkswagen and Virgin America and RadioShack and Starbucks are tracking their attempts to inject themselves into the conversation. This dashboard shows “how many times you’re mentioned, how many people are following you, and a key measure, how many people are unfollowing you,” explains a Twitter employee while demonstrating the dashboard on a silver MacBook in a conference room one morning in July.

This is the staging ground for making Twitter into a multibillion-dollar company. An advertiser like Starbucks or VW can buy access to different parts of the Twitter experience, placing its messages atop the list of the most-tweeted hashtags, or inside the Twitter feeds of people who already follow the brand, have a friend who does, or simply tweet about a related subject. Soon there will be a self-serve option, allowing smaller advertisers to sign up and instantly get into the mix. In every case, companies can monitor the response with a Twitter stock chart, the zigs and zags of how many clicks, replies, and retweets (when a tweet is passed along) are coming in. If nobody’s responding, the ad disappears.

“There’s this big gap, no doubt about it, between awareness on Twitter and engaged on Twitter,” says its CEO.

The idea is that by studying how people are reacting to a message, advertisers can experiment with different voices, personalities, pitches, and ideas and calibrate the tweet so the Twitter charts keep going up and not down. Adam Bain, a former News Corp. advertising executive who is now Twitter’s head of global revenue, describes it as “transparent” marketing.

Or maybe just more stealthy. In January, Audi promoted a Twitter hashtag in a Super Bowl TV ad, telling people to go to Twitter and talk about what the concept “progress” meant to them, using the hashtag #progressis. As the hashtag went viral, Audi’s message was circulated through a kind of conversational side door. “Essentially, when you went to the Twitter site, you saw almost the whole world entering a conversation about a concept, progress,” says Bain. “And Audi owned this concept of progress on Twitter for months.”

The goal is to make advertisers members of the influencer class, cultivating the same credibility as Kutcher and Obama and getting Twitter users to retweet them as they would a friend. “Part of the magic for us is getting marketers to be in that center,” Bain says, “and making them some of the most influential, because they have interesting things to say … The amazing thing is that people are retweeting messages from marketers at a really large rate, and it’s uniquely Twitter.”

Twitter wants to be a place where the distance between celebrities and brands shrinks to next to nothing, where retweeting an advertisement is practically a function of who you are.

Twitter’s model harks back to the early days of television, when the shows were the ads. In a way, it’s a simpler world. Reality-TV socialite Kim Kardashian charged $10,000 a tweet to promote a product to her then–2 million followers (“Check out my commercial for @carlsjr … What do you think?”). To convince advertisers to pay Twitter, and not Kim Kardashian, Twitter needs mass scale, to “surface” all manner of customers to advertisers in a predictable and measurable way, over and above what they can achieve with one or two celebrity Twitter feeds. Twitter’s not there yet.

“They don’t have sufficient scale to make them a meaningful first-tier player in the social-media landscape,” says John Battelle. “I can go to Yahoo, Microsoft, even Federated Media, and I can get tens of thousands of people I care about on a schedule I care about with returns on investment that I can optimize.

“The real business that needs to scale is the promoted tweets,” continues Battelle. “How you get the right promoted tweets in front of the right person at the right time—it’s the same problem as surfacing the content.”

Twitter could soon make a big leap in users when its network gets integrated as the in-house social media in Apple’s new mobile software, opening up the possibility of funneling some 200 million users into its service. But for every user Twitter adds, there is now the threat of losing one as well—to Google+, the search company’s Twitter-like social platform that offers more control over who sees what and when and is attached to a familiar online environment.

Twitter, as a company, has a lot of conspicuous connections to Google: Costolo and Williams are former Googlers, and famed venture capitalist John Doerr, in addition to seeding Twitter nearly $150 million, is on the board of directors at Google. Doerr’s investment motto is, famously, “No conflict, no interest.”

Twitter’s executives all told me they want to be a stand-alone company, but there’s a reasonable alternate scenario: If Facebook’s IPO goes well, and Google+ does not, Google would be desperate to solve its social-media problem, and it might make Twitter an offer it can’t refuse, making the Facebook-Google faceoff a war over whether the web exists inside a walled garden or outside one, whether it’s a private news feed or a public one.

Dorsey, the optimist visionary, believes Google+ and Twitter and Facebook can all co-exist.

“People are constantly looking for change. That’s a basic human truth,” says Dorsey. “I think people will get bored of one. We’re not at odds with each other. We’re going after different audiences with different approaches.”

Which brings us back to the folks on the third floor and the problem of making hash of all those tweets. If they can get more people to show up, stick around, and organize themselves inside a more streamlined and unified Twitter, it will give advertisers a bigger “inventory” of timelines within which to insert their messages. It also strengthens what Twitter calls its users’ “interest graphs,” allowing advertisers to target them with precision through their matrix of comments and replies and friends and followers, not unlike how a Google ad finds you through your own search. If you like Snooki, for instance, you might also enjoy a tweet from a tanning-lotion company in your timeline. Or a tweet about another MTV reality show, 16 and Pregnant. Or one about Wonderful Pistachios, the nuts she got paid to promote on TV.

Or not. Twitter has proved valuable for aggregating real-time news, or snarking about celebrities on TV—two pretty big businesses, but maybe not quite $8 billion big and certainly not enough to meet the Earth-size ambitions Dorsey has in mind.

Lindzon says Twitter is the “greatest invention in the history of the Internet,” but he is skeptical that Twitter can organize that entire vat of 200 million tweets a day into a fluid and orderly experience, billboard it with advertisements, and still retain its biggest strength—which is surprise. “I want to have that ‘aha’ moment,” he says. “If they can figure out how to monetize that, good luck.”